By TRACE BARROW

Ship fires present specific challenges for municipal fire departments that are, in many ways, unique. From the initial call to the unified command structure, municipal departments are likely to be exposed to a situation they were not anticipating. The hazards associated with ship fires and the dangers they pose to municipal fire departments warrant special consideration, planning, and training.

- SHIPBOARD FIREFIGHTING: THE BASICS

- Shipboard Firefighting: Realities and Risks

- Ship Fires vs. Structure Fires: Differences and Preparation

- Shipboard Solutions for the Land-Based Firefighter

The Response

In June 2020, the Jacksonville (FL) Fire Rescue Department (JFRD) responded to a fire on the Hoegh Xiamen while at port at Blount Island Marine terminal. The Hoegh Xiamen was a 617-foot-long, roll-on/roll-off (RORO) car carrier with more than 2,400 automobiles among its cargo. Several firefighters were injured fighting the fire on the first day. I was one of a group of chiefs tasked with working with the salvage and contract firefighters who responded to the incident. We worked together for the next six days until the fire was declared out. From this working relationship, I was afforded a hands-on look into how professional marine firefighters and professional salvage experts approached their job, prompting my department to revive our ship fire training program, with an emphasis on containment and boundary control. Some of the topics we cover are included in this article.

Vessels can be loosely grouped into the following categories to aid land-based fire departments:

- Tanked and nontanked vessels requiring a vessel response plan (VRP).

- Military vessels.

- Commercial vessels not requiring a VRP.

- Privately owned vessels.

Commercial vessels requiring a VRP are, basically, large ships that carry enough petroleum either as a cargo (tanked) or as a requirement of their propulsion (nontanked). A VRP is a federally required document for ships with these certain characteristics that serves as a plan in case of grounding, fire, or other emergency that could result in a petroleum spill. For the municipal fire department, this requirement has several important implications. The VRP spells out who will be contacted and contractually obligated to respond in an emergency. The VRP also has specific requirements for response in terms of time, equipment, and personnel. Included in these response requirements may be salvage experts, marine architects, marine chemists, marine firefighters, and many others.

(1) On June 4, 2020, the roll-on/roll-off (RORO) vehicle carrier Hoegh Xiamen caught fire during loading operations. (Photos by author.)

(2) The RORO ramp at the stern of the Hoegh Xiamen.

(3) JFRD units staged on the pier at Blount Island, where the Hoegh Xiamen was moored when it caught fire.

Knowing that these resources have been notified and are available can be a huge help for responders. The VRP is set up for a vessel anywhere in the world having the same emergency to which we are responding. The experts contracted to respond normally fly to where the ship is having the emergency and then figure out how they’re going to deal with it. Why wouldn’t we want them on our team? For chiefs, it is time to put your ego aside and accept help. Ship fires are incredibly dangerous for trained firefighters. For most of us, from firefighters to chiefs, this is likely our first real ship fire event. Go slow and consult the experts.

Response Realities

A potential, unexpected implication of the VRP is that first responders can anticipate not being the first ones called. It is highly likely that a ship’s crew will attempt to mitigate a fire onboard their ship whether it is in port or at sea. The master of the vessel will likely contact the required individuals in the VRP to notify them of the event but never notify local authorities unless the fire is uncontrollable. For responding fire departments, this means we can expect to arrive at an out-of-control fire or, at least, one that’s beyond the control of the ship’s crew. This late notification is a common theme in many ship fire events, and it can catch first responders off guard.

Beyond the initial notification complications, first responders should also be aware that vessels with a VRP will inevitably bring many stakeholders to the scene. The U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) will obviously be involved, and the captain of the port will be a key player in the process from the start. The USCG most likely will not want to take charge of the fire but will be able to offer advice and experience to aid first responders. It may also dispatch a salvage engineering response team. These experts are invaluable to advise first responders about the effects of the fire on the ship itself.

Among the stakeholders spelled out in the VRP will be the qualified individual (QI), a representative of the company named as the responding company contracted to respond to the emergency onboard the ship. The QI can request other contractors and assist municipal departments, even as far as ordering (and paying for) specialized equipment, if needed. Environmental agencies associated with state and federal agencies will also show up and have a seat at the unified command table.

Also responding to any major ship fire will be a litany of attorneys, representing anyone from the carrier to the cargo owner. These attorneys will try to get as much information from the scene as possible and will most likely attempt to limit any liability for their clients and maximize any recovery that may be owed. For first responders, it is important to recognize these individuals and the role they play in a ship fire event.

(4) A JFRD aerial was used as access to the weather deck and as a secondary escape.

(5) On day one, initial attack companies were put in place to a fight fire aboard the Hoegh Xiamen.

(6) Paint charring on the Hoegh Xiamen decks, where the cars were burning.

(7) Hull-cooling operations continued for days.

When we respond to a ship fire in our response area, we must clearly notify the ship’s master that we are not taking over responsibility for the fire; we are there to help, if requested, but not to assume liability. For example, the RORO vessel Golden Ray capsized in Brunswick, Georgia, in 2020, and the salvage cost totaled almost $1 billion. When fingers start to point, the stakes are very high. First responders should be aware that, as they arrive and involve themselves in the emergency, they may be answering expensive questions years down the road. Take good notes! You may need them years from the event. After the Hoegh fire, we placed several blank notebooks in our command van to be used for large events and saved. For events lasting multiple days, and through many command changes, these notebooks may be the best resource we have to reconstruct our response.

Commercial vs. Military

If your department has military ships in your response area, be aware of the differences in fighting fires on commercial and military vessels. For most commercial vessels, there are relatively few crew members onboard. Military vessels usually have large numbers of well-trained crew members onboard. The commanders of these military ships have traditionally fought fires in port very similarly to those out to sea. In the past, land-based departments may have been requested to stand by in case the crew was unable to extinguish the fire and only be used as a last resort, if at all.

In July 2020 in San Diego, California, the amphibious assault ship USS Bonhomme Richard caught fire while undergoing maintenance. The fire burned for several days and resulted in the total loss of the vessel. As a result of the fire, the U.S. Navy reformed how fire risks are approached while ships are in for repair. The Navy has also revamped its training with municipal departments that respond with it and has begun integrating land-based departments with Navy crews. Ships that are out to sea are usually fully staffed, and trained personnel are onboard and prepared to act. In port, it can be a different story. The crew may be split up or on leave, the ship may have ongoing repairs, and the firefighting equipment may not be in full service. Land-based departments may be asked to integrate early in a military ship fire at dock.

(8-10) Master streams, Navy tugs, and JFRD fireboats worked together for days to cool the hull of Hoegh Xiamen and keep her intact.

Working with Navy firefighters is a challenge for most municipal departments; the military has drastically different operating procedures, and ship officers run command very differently than most departments. The communication between personnel can be difficult. For land-based departments, it is imperative to train with our military counterparts. The goals of safety, accountability, and extinguishment are the same for both military and municipal departments. However, the way these goals are achieved will look foreign to most land-based chiefs.

Commercial vessels that don’t have VRPs are smaller vessels that don’t meet the federal requirements for formal contractual agreements in case of an emergency. The bad news is that the experts are not en route. The good news is that first responders are probably going to be notified early, which can be a game-changer regarding our ability to mitigate the fire. Most of these vessels have local crews, and information should be easy to obtain.

Just because these vessels are smaller doesn’t mean they can’t be challenging. Ferries may have hundreds of passengers, and tugboats may have tens of thousands of gallons of fuel. Often, these vessels are in various states of repair or disrepair. The mariners on these vessels may be part-time workers and may provide unreliable details regarding the vessel. In short, approach any commercial vessel fire with caution, and treat entries like confined spaces.

Privately owned vessels run the gamut from private yachts hundreds of feet long to small, outboard-powered crafts. In general, private boats are designed for occupancy, and layouts are more favorable for firefighters to make entry. Hallways, stairwells, and bedrooms are usually tighter, and issues with secondary escapes can make fires in private vessels more dangerous than some residential fires. However, many times, we can attack fires in private vessels using more standard land-based tactics.

Tactics

It may seem strange to think about the marine industry predating organized paid fire departments, but it actually does by many centuries. America was “discovered” by ships sailing from Europe in search of better trade routes. Even before that famous voyage, ships were being designed with thoughts of fire safety in mind. The lives of the crew and value of the ship and cargo were at stake. Hundreds of years of shipbuilding, engineering, and marine architecture have resulted in the modern-day ships we have now.

(11) Days into the operation, the fire continued toward the bow. Cooling streams were constantly adjusted for maximum effect.

(12) The interior of the Hoegh Xiamen deck, showing beam deflection and steel post collapse.

(13) In some places, the beam deflection left under five feet of clearance on the deck.

Many of the early concepts of marine firefighting are still relevant today. Those early tactics were to locate, confine, establish boundaries, and attack and overhaul the fire. Each benchmark can be related to structure firefighting, but land-based firefighters are making a mistake if they try to attack ship fires the same way they attack structure fires. Those hundreds of years of marine engineering and architecture can work for you or against you. Most of the ships to which we respond will have some form of compartmentalization available. Our first thought after locating the fire should be how we can isolate or contain it. Many times, containment may be the exact tactic we need. Once contained, boundary protection might be all that is required to mitigate the fire. Be careful when your tactics begin taking you directly toward the fire. Make sure your plan is solid; if something goes wrong after you have opened a boundary, you may lose the rest of the ship, or worse.

There are other tactical considerations we have identified that may or may not seem obvious to the land-based department. Training on ships or ship props can help departments identify areas where they may have problems and help find solutions prior to the event. For instance, bringing in relief for hose teams becomes an accountability nightmare when you have multiple direction changes down (or up) multiple decks, with members stationed at each direction change to pull hose. We’ve found that, at times, it takes as long to relieve the nozzle team as it does to make the initial stretch. If you plan to “leapfrog” relief crews, how do you manage those swap-outs, and how do you make sure the crew you send to relieve a crew makes it to the crew they were sent to relieve? If we’re not actively involved in a firefight, it might make more sense to pull everyone out on the initial hose pull, regroup, and send in another crew to advance the line. If our goal is to reach a point in the ship to form or maintain a boundary, we have the time to proceed slowly and as safely as possible.

Another training lesson has been the need to establish a rehab section, staging, and a rapid intervention team (RIT) onboard the vessel. The distance from the ship to rehab is just too far, with too many obstacles around which to send worn-out crews. A better practice is creating a smaller, temporary rehab on the ship and then sending personnel to the main rehab after they have a short rest. Set up RIT aboard the ship for these same reasons. In addition to onboard RIT, you may have to consider multiple RITs for different entry points on the ship.

Locate the Fire

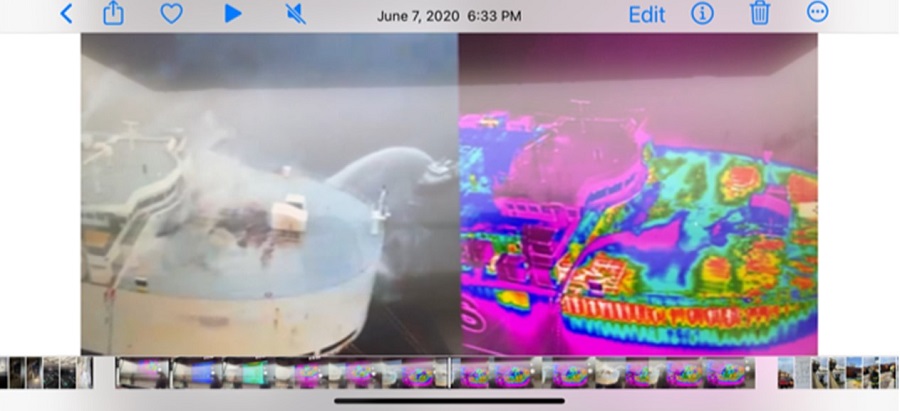

Locating the fire may be as simple as seeing fire on the deck of a ship or in an accommodation space. In that case, we can quickly establish whether the fire is spreading and put a line into service to extinguish it. However, quite a few deck fires have been attributed to fires below deck conducting heat to the deck above. We need to use our thermal imaging cameras (TICs) any time we approach a ship reported to be on fire and establish if there is heat anywhere else on the vessel. If a 360° size-up of the ship shows no other hot spots and every indication is that you’re looking at an isolated fire, you can quickly and safely access and make an attack on the fire.

(14) A steel I-beam collapse. Note the upper beam deflection and steel deck floor collapse.

(15) Still shot of live drone video feed that was used to help direct crews cooling the hull.

The fire we can’t see is a different story. For those fires, we need as much information as possible from the crew. Fire safety maps can help locate access routes, hatches, and fire boundaries. Our 360° size-up with the TIC can identify hot spots. The crew can also provide information about how to access the area, but we need to be very careful about how we follow the crew’s advice. Remember, the crew lives aboard the ship and has spent hours working in the areas they’re describing to us. They are not accounting for our gear, self-contained breathing apparatus, and unfamiliarity with ship accommodations. It is very common for fire crews to get lost following what seemed like easy directions from the ship’s crew. On a military ship, it may be possible to team up with the ship’s crew to enter immediately dangerous to life or health atmospheres to locate a fire. On commercial ships, it may not be possible to team up with ship crew members if locating the fire involves full personal protective equipment. Fire crews need to bring a charged hoseline with them; each change of direction will need a firefighter to help feed hose. Staffing requirements can easily overwhelm all but the largest departments.

Confinement

Confinement seems simple enough from a land-based perspective: using a hoseline to hold the fire. From a marine perspective, it gets a bit more complicated. One of the first things a ship’s crew will attempt to do during a fire event is to close any hatches that could allow air to the affected compartment. Since most commercial ships operate with small crews, a 600-foot-long RORO may have less than 25 crew members. Some hatches may be automatic, but there are many manual ones that need to be closed.

You may ask the ship’s crew if the hatches have been closed, and the answer may be yes. Just because you get a “yes” doesn’t mean you can assume it has been done. A standard practice for professional marine salvagers is to arrive on the scene of an out-of-control engine room fire where the extinguishing system was ineffective and close hatches, recharge the carbon dioxide (CO2) system, and refire the system.

Before we commit personnel to a fire attack, we must know which openings are open or closed. We also must control all the hatches and every door in every stairwell and monitor those doors’ temperatures. Then, we can establish our boundaries.

Boundary Protection

For most land-based firefighters, the term “boundary control” denotes a defensive operation. Being assigned to wet down the roof of an exposure next to a house on fire is not an assignment any of us are hoping for. In the marine world, boundary control isn’t as passive as that; it means that you’ve identified hot steel that needs cooling or you have identified a bulkhead needing protection. That bulkhead or hot steel may be several decks down into the ship, or it could be the exterior of the ship. Either way, the cooling of hot steel is actively attempting to maintain the integrity of the ship and keep it from breaking apart. Ships are designed to displace water and can withstand massive amounts of pressure pushing on them from the outside.

When superheated steel begins to expand and weaken, it puts stress on the ship from the interior for which it wasn’t designed. A large fire on a steel ship can create enough stress that the ship can crack or break apart. Once the ship breaks apart, the damage to the environment, the blocked port access, and the actual cost of the salvage can be in the hundreds of millions of dollars, easily. Suffice it to say, boundary protection is a very important aspect of the ship fire process. Once we have established the fire’s likely location; closed all of the vents, hatches, and doors for that area; and established boundaries, we can plan our fire attack.

Fire Attack

A critical question we must ask early on in any ship fire is whether the ship’s crew has fired the extinguishing system. Onboard systems could include CO2, water mist, sprinkler systems, foam systems, and so on; it depends on the cargo the ship was designed to carryor the area the system is designed to protect. As land-based firefighters, we want to know if it has been used and, if it was, if it worked. We may need to wait for the system to be effective. A time of 48 to 72 hours isn’t unreasonable to allow these systems to have a chance at full extinguishment. In the meantime, we can monitor boundaries and doors and work to potentially recharge the system.

For the system that was fired and didn’t work, we need to find out why. Most times, the system was fired prior to the vents being closed. However, the cargo space may have been loaded with something the system wasn’t designed to extinguish. Many dangerous goods are shipped undeclared; there may be electric vehicles burning out of control or the system may have been sabotaged. These scenarios have been factors in large-vessel total losses in the past few years.

We have already established closing vents as a priority. Once we close them, we can attempt to recharge the system and use it, or we can simply maintain our boundary control until the product burns out. If we determine that the system failed because the product burning overwhelmed the system, we should be in position to adjust our boundaries. Keeping the ship afloat may turn out to be the best we can do.

From a manual firefighting perspective, ships are equipped with fire mains, which are supplied by primary and secondary fire pumps. These systems may supply fire hydrants, hose stations, standpipes, sprinklers, and so on and may also be interconnected to things such as the anchor wash, ballast tanks, and other ship systems. Fire departments can augment this system using the international shore connection (ISC), an adapter plate made to allow another ship or the fire department to supply the system even if the connections are not the same.

Fire departments must be aware that the ISC connects to potentially thousands of feet of pipe, and the status of that piping and the valves is unknown to responding departments. In addition, the connections at hydrants or standpipes may not work with standard fire department hose. Responding departments should plan to use their own hose and nozzles for attack lines. The ship’s hose may be useful for boundary cooling or exterior attack hose but should not be relied on for interior attack.

Land-based fire departments should plan to hook up to the ISC and be prepared to supply it if the ship’s crew advises. However, they should not confuse the system with the typical structure standpipe we are more accustomed to.

Overhaul

For the vessels with a VRP, it is very likely that contractors will be on scene to assist with overhaul. Land-based departments should expect these professionals to take over salvage and overhaul operations as soon as possible. For the vessels without VRPs, command should consider every resource at its disposal and, if possible, get the vessel out of the way of commercial traffic. The question will eventually come down to who’s going to pay for the storage or removal of the vessel. The sooner we can remove ourselves from the conversation, the better.

If we are working in a ship that has a questionable atmosphere, keep in mind that marine chemists are available to certify confined spaces. If we are stuck with the problem, put a marine chemist on board to certify that all areas of the ship are clear before personnel are allowed to go off air.

Other Considerations

The vessel’s stability will be a major topic as the fire progresses. As land-based firefighters, we must be aware that every gallon of water we put on the ship will have to be removed, eventually. In almost all cases, the water will not be allowed to be pumped overboard because of pollution concerns. As we cool boundaries, we should direct as much water as possible off the hull. If you’re cooling an interior boundary, use as much water as necessary but avoid excessive runoff.

Early on in the response, record draft marks on the vessel and on a regular schedule note them for any changes. A picture of the draft marks can serve as a record as well as provide information about other changes as the event progresses. Each U.S. coastal zone and certain major inland bodies of water are covered by a document known as an Area Contingency Plan (ACP), a federally required document assembled and maintained by the USCG that spells out who would respond and what processes would be initiated in case of a major pollution spill or potential spill. Included in the ACP are situations that could arise from a major ship fire within the zone along with a salvage and marine firefighting plan. The plan is a huge resource for departments for planning and training purposes. Resources are named and contact information is included.

A major ship fire is a high-risk, low-frequency event for any fire department. These fires combine almost all the dangerous conditions we face into one event. Communication is difficult, and our personnel operate in conditions to which they may never have been exposed. Very little about the ship will be designed to make egress easy or quick. Approach ship fires with extreme caution. Some situations could warrant a fast attack, but there are also situations where we should be setting up for a days-long event from the very beginning. The old question, “How do you eat an elephant?” comes to mind. We should approach these events slowly and make small, measured progression, step by step.

TRACE BARROW is a 26-year fire service veteran and a battalion chief with Jacksonville (FL) Fire Rescue Department (JFRD). He is also a state-certified paramedic, a licensed United States Coast Guard captain, and a hazardous materials technician. Barrow previously served as a JFRD marine battalion chief.