BY DON DOYLE

As a firefighter or company officer, imagine responding to an industrial site you know nothing about for a working fire. While responding, you see a dark thermal column rising from the area. On arrival, you are trying to gather incident information from someone who doesn’t speak understandable English. Through pure determination and a smartphone app, you find out that there is a need for a confirmed rescue in the fire area.

- SHIPBOARD FIREFIGHTING: THE BASICS

- Shipboard Solutions for the Land-Based Firefighter

- POLITICS OF A SHIPBOARD INCIDENT

- FIRE IN THE HOLD SHIPBOARD DRILL

This rescue requires firefighters to climb down into the basement of the machinery space, three floors below the main floor, an immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH) atmosphere with near-zero visibility. Here, you must leave the safety of the stairwell and search a complicated area about the size of a basketball court with huge obstacles blocking your efforts. Now, find and extricate the victim. Add height and weight limits that may affect your apparatus placement as you approach the incident or missing floor plating and stairs that lead to nowhere. If you’re in the fire service and you have ships frequenting your port facilities, this is the potential scenario.

I wrote “Shipboard Firefighting Training from Scratch” (Fire Engineering, November 2015) explaining how the Maritime Fire and Safety Association (MFSA) serving the lower Columbia and Willamette Rivers and the Fire Protection Agencies Advisory Council (FPAAC) rebuilt our shipboard firefighting training program after the 2008 economic crisis. The photos in this article depict FPAAC training. With dedicated people and smart management, it continues to grow. It will withstand future downturns in our economy and continue to supply an effective fire response to a shipboard incident inside our operational areas.

(1) Responding to a fire involving a ship is probably the most complicated and dangerous job firefighters will face. (Photos by author.)

(2) Not knowing the construction and layout of a ship adds to the danger, especially in this engine room.

When I wrote that article, our strategies and tactics for firefighting onboard a vessel were solid. Like every other fire service agency, we will operate with an appropriate strategy and commit resources to support that strategy. We have a tiered response of trained personnel. We conduct quarterly and annual training to support all levels, and we challenge each other to improve. We have reviewed National Fire Protection Association 1405, Guide for Land-Based Fire Departments that Respond to Marine Vessel Fires. What we have learned and worked into our training curriculum is much more complicated than we had been taught in the training we’ve received through the years. Using bulk carrier ships and an engine room fire as an example, I will focus on the realities and the risks.

Reality: A ship is a mobile industrial facility, usually from a foreign country, as described in the opening scenario above, with all the potentials of an industrial site that might be in your jurisdiction. Onboard a ship, you will find hazardous materials, high voltages, high-pressure hydraulic lines, and Class A and B fuels, just to name a few. Depending on the ship and the crew, in most cases, these hazards can be reduced greatly by diligent housekeeping and maintenance practices. Or, in a few cases, the opposite can occur. Keep in mind, I’m describing the worst of what I’ve seen. You must understand what you could find and not to be surprised by it.

Chief of Marine Operations (Ret.) Craig Shelley from the Fire Department of New York has written a number of Fire Engineering articles on fighting fires in the maritime environment. If you are a land-based firefighter, a company officer, or a command officer with shipboard firefighting responsibilities, you need to read his work, especially if you have the potential to be first due at an incident involving a ship.

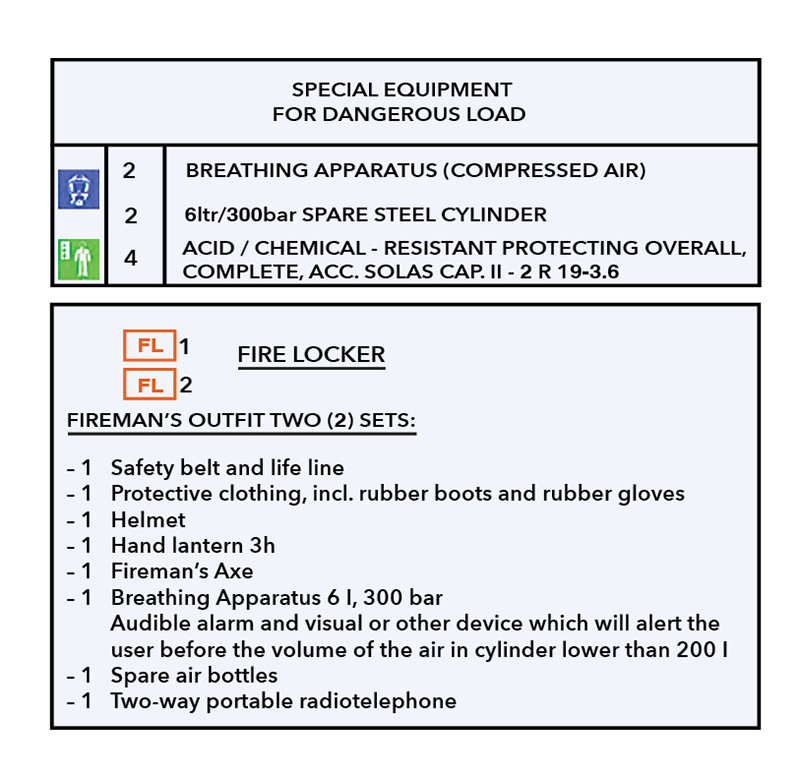

Figure 1. Special Equipment

This is a typical listing on a vessel’s FCP. Notice that it lists “rubber boots and rubber gloves” as part of the PPE. (Figures by FPAAC.)

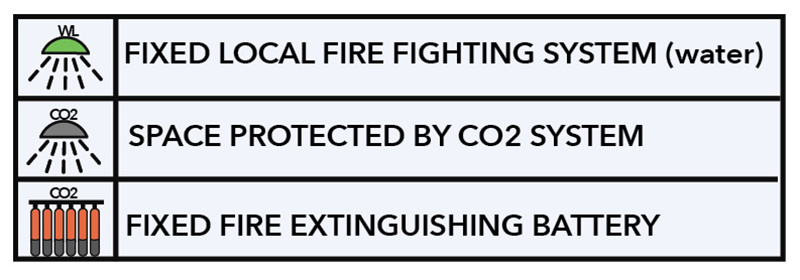

Figure 2. Fire Control Plan

Here are the common symbols on the FCP for the CO2 battery and the symbols that correlate to the protected spaces.

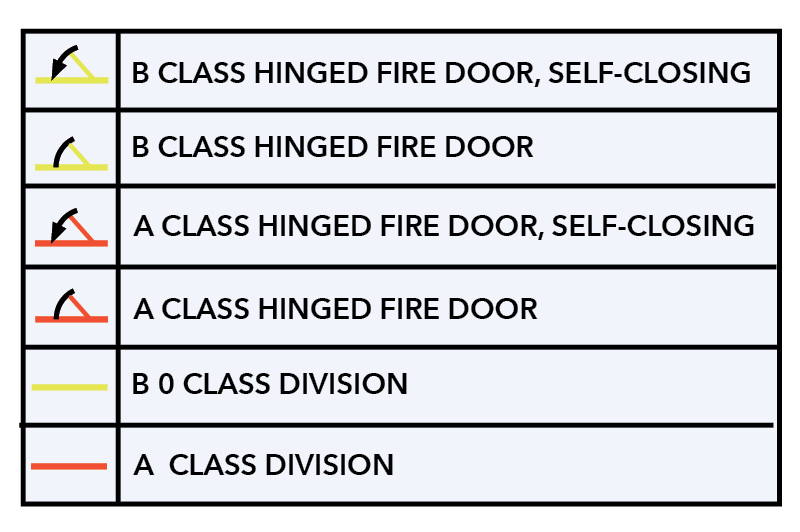

Figure 3. Fire Boundaries

The fire boundaries as listed on the FCP. The Class A boundaries are fairly easy to find on the FCP; firefighters need to know where the boundaries are and where the doors are located before entering a fire compartment.

Shelley points out that in some cases, and depending on where they received their training, the crew’s skills and ability to mitigate a fire onboard a ship can be an issue. Training a ship’s crew to the standards required by maritime law is a responsibility enforced in the United States by the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG). Not all countries enforce these laws as strongly as the USCG; fire service personnel should be skeptical regarding the ship’s crew’s training at the onset. This is not true of all foreign flagged ships and crews, but the fire service should use caution until it is proven otherwise.

Since 2001, English has been recognized as the required language of professional mariners worldwide, with a few exceptions. In my 25 years of experience in dealing with ships’ crews, I’ve almost always been impressed by these maritime professionals who come from outside our borders and their ability to speak and understand English. Reality: Recently, we encountered a crew who could not communicate in English except for the chief engineer. Luckily, he spoke both English and Tagalog fluently and knew the ship as an expert mariner.

By maritime law, the ship is required to have fire detection and fire suppression equipment. This equipment includes the personal protective equipment (PPE) of the crew members handling hoselines to the seat of the fire compartment. Since most fires onboard a ship are engine room and Class B fires, the PPE should be of an appropriate quality for such duty. Reality: Unfortunately, this is not the case on most foreign-flagged vessels and crews. Typically, you will find older steel bottle self-contained breathing apparatus and lightweight PPE not suitable for intense heat. In some cases, there may be only two sets of this PPE, referred to as a “Firemen’s Outfit.” In training, we were taught to use crew members as guides into the fire compartment. Obviously, with this type of PPE, they won’t be able to take us much farther than the opening into an engine room.

Hoselines are usually single jacketed with quarter-turn couplings or some odd combination that’s not compatible with fire service equipment. It’s common to find a hose coupling secured to the hose using wire wrapped tightly multiple times around the hose. A “fire station” can be a box located in the engine room, the cargo decks, or around the exterior of the ship. It may be equipped with around 50 feet of the hose described above, a foam eductor, a nozzle, and a five-gallon bucket of Class B foam. A discharge port from a fire main should be located nearby.

Just as in an industrial facility, there is a wide selection of fixed and mobile fire suppression systems available. A ship may depend on one or more systems such as carbon dioxide (CO2), water mist, and high- or low-expansion foam. All must include the engine room as a covered compartment.

(3) The ECR, as it appears on many plans, is on every commercial ship, adjacent to the main engine and generators that power the ship. The ECR on this ship has no protected escape route. Crew members working here will be forced to enter the engine room, with all its potential hazards, to find a safe egress route.

(4) You can determine a lot about a ship by its external condition and appearance. A deteriorating appearance can mean trouble with the ship’s ability to stop and extinguish a fire.

(5) Firefighters and officers are practicing how to access and egress areas of a ship using the ship’s FCP. This is a perishable skill that needs to be exercised in the classroom and on the ship. A ship’s FCP can seem large and intimidating without practice; it can be as big as 3 × 5 feet and include multiple sheets, depending on the type of ship.

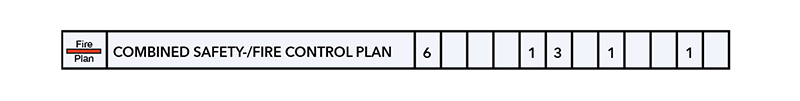

Figure 4. The FPC Location

The common symbol for identifying the FCP on a ship. This ship has six copies on four decks. If possible, at a large incident, the operations section, division, and group leaders should have a copy retrieved for their use.

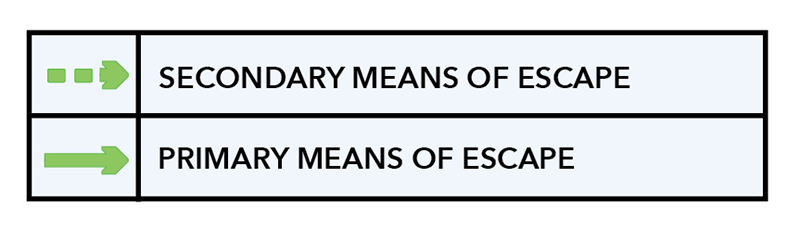

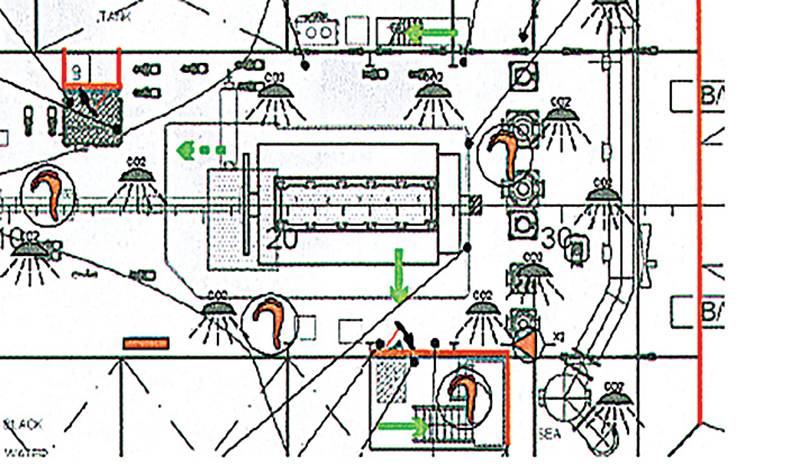

Figure 5. Primary, Secondary Escape Routes

On many ships, these escape routes are clearly painted on the decks of the machinery spaces.

Figure 6. Primary Escape Routes and FCP

Once you can identify the primary and secondary escape routes and correlate them to the FCP, your chances of becoming a rescue victim yourself have been greatly reduced.

Machinery spaces must be separated from living areas by a Class A boundary that is constructed from steel or the equivalent, covered in structural insulation that prevents the passage of smoke and fire for at least 60 minutes. All openings from the Class A boundary must be protected by the equivalent fire protection ratings with self-closing doors. Reality: Self-closing fire doors have been known to be tied open to make passage easier for the crew traveling to and from the machinery spaces, just like we see sometimes at a plant site.

Every commercial ship has an engine control room. It may or may not be protected by a Class A boundary. The engine control room is where the main engine, generators, and other mechanical systems are monitored and controlled. Reality: Depending on the ship, crew members may be required to exit the engine control room, enter the fire compartment (in this example, the engine room), and travel to a primary or secondary egress route.

If everything is in proper working order and used as designed, a fire in an engine room should be sealed inside that compartment and extinguished by the fixed system. Reality: Unfortunately, systems fail for a few reasons. This is especially true of extinguishing agents—e.g., CO2: The space has not been sealed properly, the system wasn’t used, it was used too late, it failed to operate because of lack of maintenance, or the system wasn’t allowed enough time to “soak” and the fire reignites. Using the ship’s crew to identify and close doors, hatches, and ventilation to the fire compartment is a must. In almost all cases, this can be accomplished from the exterior.

(6) Firefighters onboard a ship find out where they are going, what their assignment is, and what the objectives are, reading the FCP with the chief engineer to understand where the access and egress routes are before entering the IDLH.

I can hardly think of any place that puts fire service personnel at more risk than a fire in this compartment. Except for rescuing a crew member, we should look at this fire as we would one in an industrial setting. Seal the space if you can, and let the fixed system work. Monitor the fire and set up boundary cooling as needed. Attacking an engine room fire from the main deck is dangerous, time consuming, and laborious.

The secondary egress point of every engine room is the escape trunk. This space is enclosed by a Class A boundary and allows the crew to exit this compartment and emerge to the main deck using vertical ladders through a watertight door or hatch. Is this a good access point for a direct fire attack at the machinery floor level or bottom deck? My answer is, “Yes, but.” This will require firefighters to lower a hoseline to the bottom, open the fire boundary door, and proceed forward dragging the hose behind them.

Let’s say the situation starts to deteriorate, the space is no longer tenable, or a defensive strategy has been declared. The firefighters will need to exit the space back through their access point, the escape trunk, and now the door is fouled by a hoseline possibly converting the only escape route into a chimney. You better have a plan to cut and run if needed.

In the case of an engine room fire with a rescue, we have emphasized the Class A boundaries a lot during our training. The crew will go through this boundary to escape a fire, even if they’re injured. We need to search these places first for missing crew members before risking the firefighters’ lives. In an engine room fire scenario, places to search would be the escape trunk and the aft steering room, which are both separated from the engine room by a Class A boundary.

When I try to describe a ship’s engine room, one word comes to my mind—massive. The first time you descend down to the engine room floor, you are reminded of how deep you are from the main deck, below the waterline and confused as to which way is forward or aft. You look up and realize that the main deck, where you entered the machinery space, is at least 40 feet or more above you, and you’re standing on the machinery floor that’s close to 1,000 square feet.

This is a good place to discuss the ship’s fire control plan (FCP). There’s a ton of useful information on an FCP—the layout of the ship, how to get from one place to another, and where the primary and secondary access points and the Class A boundaries and openings are. If you are an operations section chief or a group or branch supervisor, having an FCP with you and someone who knows how to read it is essential.

By maritime law, a ship is required to have multiple copies of the FCP stored around the inside of the ship and posted for the crew to reference in an emergency. Standard shipboard firefighting theory tells us that the FCP will be located at the top of the gangway when you access the ship. Reality: As a rule, you probably won’t find the FCP at your access point onto the deck. Depending on the type of ship, it will most likely be in a container mounted to the superstructure at the main deck and should be a contrasting color. The words “FIRE CONTROL PLAN” should be written on that container. Reality: Although this is the quickest FCP to access and retrieve, unfortunately, its container is also exposed to the weather. I have seen plans from this container disintegrate when we pulled them out and tried to spread them out on the deck.

Knowing the primary and secondary escape routes must be the priority of every firefighter before committing to an offensive strategy or rescue below the ship’s main deck. These routes are marked by a dashed green arrow for the secondary route and a solid green arrow for the primary route. These are the common symbols for these routes. Reality: Good news! On many ships, these escape routes are clearly painted on the decks of the machinery spaces.

Looking back at the industrial scenario at the beginning of this article, it’s easier now to compare shipboard firefighting to the skill sets that many of us already possess. Industrial sites have height, weight, and width restrictions of which we must be aware and, hopefully, your prefire plans reflect those hazards. A port facility will have docks and piers with the same restrictions. An offensive strategy for an engine room fire on a commercial ship means companies pulling hoselines down narrow and steep ladderways to reach the floor level deck, similar to what you might find at a grain elevator. Extricating a nonambulatory victim from the engine room floor will take multiple crews, a lot of determination, and practiced skills. Missing deck plates are common when the ship’s crew is performing maintenance on stationary equipment and become a fall hazard in low visibility.

Regarding the language barrier you might encounter, responding to a fire at one of the Longview (WA) Fire Department’s larger facilities, I recall there was such a panic with no one speaking recognizable English until a supervisor arrived and gave us a briefing. Having English as a second language and being in a panic won’t make things easier.

The USCG maintains a list of ship inspections from around the world; in most cases, the maritime safety laws and standards are enforced equally. Ships can be detained or held over until they can pass fire and life safety regulations before traveling. Reality: Occasionally, a ship coming from another country will slip through the cracks and end up being a top media story.

If you’re a firefighter or company officer with a port facility in your area that ships frequent, you must get onboard these ships and look around. You will usually find the crew welcoming, respectful, and curious about you. Reality: Wear fire department T-shirts or sweatshirts. Leave your Class B shirts and badges on the rig; in some countries, people wearing badges can cause discomfort and you might not get a good vibe.

Get the ship’s FCP out and go over it. Ask if you can spread it out on the deck. Find the primary and secondary escape routes. If it’s raining, find an interior space to look it over. In most cases, the ship’s officers will be excited to explain the layout to you. Enjoy it. Learn from it. Reality: If you can’t read and understand a ship’s FCP, you don’t know where the primary/secondary egress points are, and an offensive strategy has been declared or there’s a rescue below the main deck, you’re in trouble as soon as you cross that plane from nonIDLH to IDLH.

DON DOYLE retired as a lieutenant from the Longview (WA) Fire Department and has more than 25 years of experience with shipboard firefighting for land-based firefighters. He owns Maritime Fire Training LLC and since 2012 has served as the FPAAC training coordinator.