BY DAVE WATERHOUSE

When aspiring fire service leaders talk about what appeals to them about progressing in their careers, not many of them place “fire department budget responsibility” at the top of the list. Not only did few of us get much training in basic accounting, but the very idea that we have to justify—some might say beg for—adequate funding for such a vital service can be hard to reconcile. So why don’t communities simply provide “sufficient resources” whenever their fire department asks for money? Why do communities and elected officials seem to see the fire department only as an expense, not an investment? These questions have piqued my interest for a long time as I was coming up in the Montreal Fire Department.

In 2014, I stumbled on a report by Arizona State University (ASU) on the economic impact of fire suppression efforts by the Phoenix (AZ) Fire Department that not only changed my thinking on the value that fire departments provide but also changed the course of my career. I got to know and subsequently began a long-running research partnership with François Delorme, an economist and a consultant who teaches in the Department of Economics at the University of Sherbrooke. Together, we have undertaken seven research projects on the economic impact or economic benefits of various specific incidents and types of emergency operations in fire departments throughout Quebec, Canada.

Exploring the Economics of Fire Protection

We are not the only ones—besides the original ASU study—to ask these questions. There is a growing body of literature attempting to quantify the economic impact of various types of fire protection. In “The Economic Benefit of the Fire Service” (Fire Engineering, March 2021), I provided an overview of the previous literature and outlined how the return on investment (ROI) for fire suppression and emergency medical services (EMS) operations can be calculated using these established methodologies. Some readers might have been surprised by ROI estimates as high as 2,100% in the earlier article. The scale of the numbers is frankly astounding—especially when as a service we have long struggled to articulate our value. The previous paper differed from earlier research in the field in that it looked at both fire suppression and EMS calls. A key intent throughout this body of research is challenging the common perception that fire protection in local communities is simply an expense that must be borne—and borne as inexpensively as possible. Rather, fire protection in local communities is an investment whose dividends and returns can be quantified using established economic impact approaches.

As we conducted these previous studies, we focused exclusively on the economic impact of emergency operations for fires in commercial buildings and EMS calls. This left a larger question unresolved: How can we quantify the economic value of those emergencies that did not occur because of the various fire prevention and community risk reduction activities that our fire departments have delivered? The more we presented about our research, the more questions we received about how to quantify what did not occur.

In 2019, Quebec’s Association of Fire Chiefs and Civil Security Managers asked us to take on this exact research question. To do so, we focused on a diverse set of city fire departments: Laval, La Matapédia, and Thetford Mines. La Matapédia and Thetford Mines are representative of many communities in Quebec; they are spread-out, rural communities with part-time or volunteer staffing.

To our knowledge, there were no other studies of this sort for fire departments. We began with an extensive literary review, and we came across a lot of very interesting research papers and publications that address the economic impact of fire departments. For example, Eric Saylor’s “Quantifying the Negative (QTN) Approach,” France’s Valeur du Sauvé methodology, and Dan Byrne and Lee Levesque’s South Carolina Institute of Leadership Equation are all examples of different paths taken to economically value the role of fire departments in their communities.

Quantifying What Did Not Occur

Determining the ROI for an emergency incident is complex; determining the ROI for what did not occur—emergency incidents that were prevented in the first place—is far more challenging. But here again, we were not the first ones to ask these questions. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) in the United States and other national organizations in Canada and Australia have attempted to quantify the total cost of fire (TCF) and the value of what was saved in a fire across whole countries over many years using large national datasets. This approach provides a foundation to assess the economic value of all fire departments, all fire prevention activities, and all fire protection investments nationally but not their value locally.

The investments (sometimes thought of as “costs”) in different fire prevention initiatives represent an exhaustive inventory of data related to fire prevention and fire incidents. Unfortunately, we found that few fire departments collect or maintain sufficient or reliable data for each of the components of the total cost of fire reports. In light of this, we concluded that with the local data currently available, a calculation model adapted from the TCF could provide us with robust results. This would allow us to develop a methodology capable of providing an outcome that demonstrates accurately the economic benefits of fire prevention activities.

Fire Prevention Types

To better distinguish the investment types made, we needed to separate the two types of fire prevention. The first type is active-passive fire prevention—e.g., sprinklers, fire extinguishers, fire-rated doors, and fire-rated egress stairwells that are code-mandated building features reinforced by regulations, construction permits, and code compliance inspections.

The second type consists of the discretionary fire prevention initiatives that the fire department conducts, based on their various risks and different needs according to the community’s social, economic, and building stock composition. To address all the numbers included in the fire prevention initiative investments, we looked beyond the fire prevention division budget, going so far as to calculate the per-hour time cost of fire station open houses, for example. This gave us a more precise overview of all the investments made in local fire prevention.

These two fire prevention investments combined and added to all the fire investigation investments represent the total amount a given fire department invests in fire prevention from year to year, going back as many years as possible.

The Economic Benefit of Fire Prevention

So how do these fire prevention investments generate an economic benefit or impact? It comes from a strong demonstrated correlation between the investments made by fire departments over the years in their fire prevention program and the overall increase in the cumulative value of the building stock in a city, year after year.

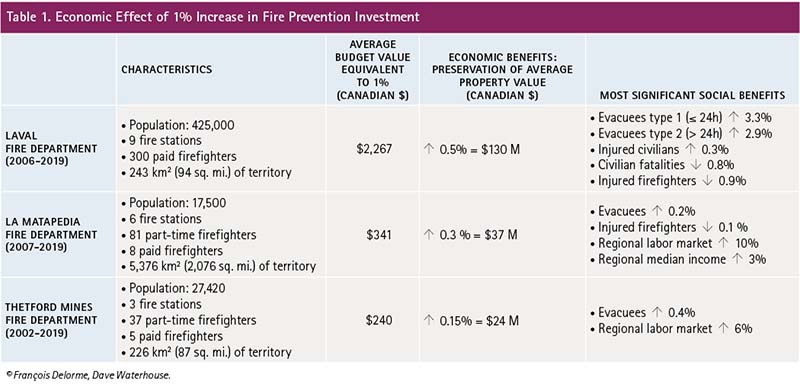

Investment in fire prevention decreases the likelihood of a fire occurring in buildings, preserving the value of the buildings over the years, and preserving the overall annual increase in the value of all the buildings for a city. With an ROI point of view, the return can be calculated by making a relation between the annual investments made in fire prevention and the annual increase in building value. To compare various approaches, we presented the results as the overall economic preservation in dollar value per 1% increase in fire prevention investments annually (Table 1). Put simply, there is a robust cause-and-effect relation between the investments made in fire prevention and the annual increase of the total building valuation for a city, giving fire prevention its economic benefits.

As the Benjamin Franklin saying goes, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” In proof of this quote, if we had taken the ROI metric as a percent yield in relation to the initial investments made in fire prevention, the results are 1,000 to 10,000 times those of fire suppression efforts.

You probably think that there are a lot of ways that the cumulative value of all buildings in a city increase. Property values and tax assessments typically appreciate (or occasionally depreciate) annually based on factors such as recent real estate transactions, improvements in the local economy, the prosperity of local corporations, and large public investments in schools and other infrastructure, just to name a few. Our study demonstrates that fire prevention investments have a greater impact on those economic variables, the preservation of the overall building value for a city.

Thankfully, we have largely removed the threat of urban conflagrations that have marked our history—except, notably, the emerging threat of wildland conflagrations in the wildland urban interface (WUI). In most urbanized settings, the application of modern codes and regulation, the widespread adoption of fire-resistant building construction techniques, sophisticated detection and fire suppression systems, and overall better community risk reduction planning have largely confined the fire risk to specific buildings rather than whole neighborhoods.

The Fire Prevention Strategic Dilemma

We attempted a more in-depth comparative analysis between the different case studies to try to understand the disparity in the prioritization of fire prevention efforts. There is an imbalance in the allocation of fire prevention resources between what is a priority given the main cause of fires (human behavior) and what is economically the most profitable, in the light of the studies carried out (active prevention/passive by regulation).

The strategic dilemma of fire prevention, considering our research, is as follows:

1. A large part of the economic benefits of fire prevention comes from investments in active-passive fire prevention, mainly through regulations. In addition, investments in active and passive fire protection in buildings are, as added value, passed on to building owners, developers, tenants, and building operators throughout the building’s life cycle. There is then a great economic and social benefit for the safety of the public, resulting from the large part of investments made obligatorily by the owners of buildings.

Active-passive fire protection for the self-protection of a building is the quickest, most reliable, and most efficient way to ensure that a fire incident is detected; the fire department is called; the occupants are notified; and extinguishment is started, if necessary, to contain the event. This protection also allows firefighters to intervene safely, quickly, and efficiently. Social variables are also winners because fire protection with active and passive means in buildings reduces the number of injured and deceased citizens and firefighters.

Proportionate to the overall economic and social benefits that active-passive fire prevention provides, the amount of resources that fire departments invest over time is minimal, resulting in great ROI.

2. Because more than 55% of fires are caused by a human factor, investments in discretionary fire prevention activities, targeted to change dangerous behaviors and raise awareness, represent the majority of all resources invested in fire prevention.

Contrary to active-passive prevention, which requires an initial investment during the building’s construction allocated mainly to promoters and contractors, discretionary prevention must be repeated and must adapt its response to the causes that investigators have identified or to the different socio-demographic changes in a city to properly target the fire prevention campaign.

Occasional events such as public gatherings constantly influence the allocation of resources to discretionary prevention activities. Active-passive prevention does not have this constraint. This repetition over time and the adaptation of constant discretionary prevention activities with the investment of time and resources, although necessary, cause the variation in the results of the economic and social benefits, compared to active-passive prevention, all from an ROI perspective.

Discretionary prevention activities take a lot of resources and must be infinitely repetitive and adapted. The financial resources should be renewed annually, but this type of prevention addresses the root causes of most fires. The results, although highly probable, are however uncertain, variable, and difficult to quantify.

Therefore, from a financial and an economic point of view, active-passive prevention hands down is the financial equation of ROI, hence the strategic dilemma. The objective is to demonstrate the economic and social benefits; this conclusion is consistent with the initial purposes of the studies we did.

We believe that, because they greatly complement each other, neither fire prevention option should be favored over the other. The efficiency of the measures taken to implement a comprehensive fire prevention program is an important point of view that should be explored.

The Social Benefit of Fire Prevention

For our research, we’ve split the social from the economic part because they are two distinct ways to value fire prevention, as we’ve found out. We asked ourselves the following: (1) What are the most significant social variables (deaths, injuries, evacuees, median income, quality of air, regional, employment, and so forth) on which fire prevention has the most effect, and (2) can we give it an ROI metric? We started by sorting out the data on citizen deaths, injuries, building occupants, evacuees, and firefighter deaths for all fire-related residential buildings.

The results (Table 1) are indicated as a percentage of variation in time for all the years of data studied. We had the same robust correlation for all the social variables indicated in the chart, in relation to a 1% of annual budget increase in fire prevention initiatives. Note that the increase in the number of injured civilians is good news, considering that the number of civilian fatalities decreased.

We can extrapolate by saying that, when there was a fire-related incident in a residential building, civilians suffer only injuries, not death, or they fully evacuate the building because of the 1% invested in fire prevention initiatives over time.

The ROI Value from the Social Benefits of Fire Prevention

To put a more precise ROI metric on the social benefits of fire prevention, we would have to put the value of a statistical life (VSL) in dollars for each yearly civilian death and calculate the dollar value of decreasing the number of these deaths. We would also have to do the same for civilians injured because of a fire. The research was not extensive enough on the matter or accessible for us to go down that road at the time of the report’s publication.

Our research has raised some interesting questions. For example, how do we distinguish between two people who both live in the same 200-unit condo tower but who had different experiences in a fire?

- Person 1 had to evacuate during a fire alarm and was outside of his home for 20 minutes before being allowed back in.

- Person 2 had to evacuate because of a kitchen fire in his home and had to relocate for approximately two months for renovations before moving back home.

Would the fire prevention efforts have the same social value for both of them, and can we calculate such an assumption? The answers to these questions could enhance the value of fire prevention efforts and make the actual results more conservative. To reflect this topic, we have established the evacuated people from fire-stricken homes as evacuees of type 1 (≤ 24 hours) and type 2 (> 24 hours).

For La Matapédia and Thetford Mines, as to the most significant social benefits, we have yet to explain precisely how and why the investments made in fire prevention have such a significant increase in the respective labour markets for both cities and in the regional median income for La Matapédia (Table 1).

Our best hypothesis so far is that the preservation of regional major employers of each city by investing in fire prevention has a bigger overall regional reach in the identified significant social benefits because of the extent of each direct and indirect job preserved, relative to the size of the population for each regional city. Regional employers operate mainly in the primary and secondary sectors of the economy, which almost multiplies by 10 their contribution to the local and provincial gross domestic product, giving each job preservation a larger social weight.

Initiatives with the Most Added Value

A lot of people asked us what fire prevention initiatives have the most added value, have the most economic benefit, or can save the most citizens from a fire. The answer is not crystal clear because the scope of our study was initially at a higher level. We initially set out to find if we could develop a certain methodology to permit us to quantify the economic benefits of fire prevention. So far, we’ve accomplished that.

To achieve a certain level of value creation for the community, the right fire prevention program comes from a dynamic and thorough analysis of the risk a fire department covers, with quality data in hand. The fire investigator’s report is one of the cornerstones to build on as well as an adequately processed community risk reduction plan and all the fire officer’s incident reports. So, the better the analysis with the right data, the better allocated the right resources will be, where ultimately the local fire department will create the most economical and social value.

To enhance the fire prevention program’s efficiency with limited resources allocated, sometimes value can be added through the reengineering of some of the fire prevention program’s processes. This can improve the economic and social benefits of fire prevention over time.

Among some of the innovative ideas for increasing fire prevention efforts’ effectiveness are those of Dr. Matt Hinds-Aldrich (who assisted me in writing this article) in his 2014 article, “This economic theory can change fire-code compliance: Behavioral economics is an emerging trend that fire chiefs can use to improve fire-safety behavior.” He underlines the struggles of fire services with the fundamental question of how to encourage fire code compliance. The traditional approach is to use warnings and fines to incentivize compliance and punish noncompliance.

Hinds-Aldrich proposes to use behavioral economics, widely used in marketing to improve the efficiency of some fire prevention initiatives that address the change in fire safety behavior and code compliance by citizens. This example illustrates how much value can potentially be created by being smarter and modern with on-field fire prevention operations, thus adding value to the process and ultimately impacting positively the economic and social benefits in the long run.

The greatest achievement with our latest research is demonstrating the economic and social benefits of fire prevention as a whole. We’ve also found out that there’s a lot of room to explore other perspectives that would help have a more precise size-up of how and where a fire prevention program can have a bigger payoff to the benefit of the community and firefighters themselves.

As an example, we have yet to explore the economic and social benefits of wildland fires prevention and suppression efforts for all agencies. Thanks to the developing branch of environmental economics, by measuring the economic value of an ecological asset of biodiversity, such as a forest, fire departments would enhance the ROI of their prevention efforts. This also makes the ROI number of our research more conservative.

It certainly comes as what’s next by looking forward, motivating us to do more research and pursue our journey to better value fire departments as a key economic player.

People are welcome to reflect with us at any time on this matter.

References

Hinds-Aldrich, Dr. Matt. “This economic theory can change fire-code compliance: Behavioral economics is an emerging trend that fire chiefs can use to improve fire-safety behavior.” www. Firerescue1.com. https://bit.ly/3Mh82QU.

Saylors, Eric. “Quantifying the Negative: How Homeland Security Adds Value.” Homeland Security Affairs. https://www.hsaj.org/articles/9307.

Swan, David. Approche économique pour les SDIS : valeur dusauvé et valeur économique de l’activité. Aix-Marseille School of Economics. https://bit.ly/3FMtB9L.

Waterhouse, Dave. “The Economic Benefit of the Fire Service.” Fire Engineering, March 2021.

DAVE WATERHOUSE is a 23-year veteran of the Service de Sécurité Incendie de Montréal (SIM) and division chief for SIM’s training division; he also oversees the Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Bureau. He is involved in research in Canada and the United States on the economic impact of fire departments in their communities. He is a teacher at Montmorency College, has a bachelor’s degree in management from HEC Montréal Business School, and has an MBA from Sherbrooke University Business School.