By Leigh H. Shapiro

Are you the type of fire officer that provides guidance, leadership, and mentoring? Or, do you barricade yourself in your office for the entire shift only to come out for calls, food, bathroom breaks, or when your relief shows up? Are you taking the time to explain and teach the probies assigned to you and your house about the intricacies and nuances of the job. Or, are you quick to dismiss inquiries and curiosities, rush “back to the barn” so you can flop into the chair or on the bed, completely ignoring teachable moments for your crew (including the more senior members)?

Are you setting the tone for the crew and the firehouse to create a productive and inclusive work environment? Or, are you phoning it in, dumping it all on the senior firefighters to do your job and then whining when things are screwed up? Are you laying the groundwork for everyone to perform not only their own jobs but yours as well so that, when you are off, they know what to do, how to do it, and what the expected outcome is? Or, are you overly reliant on the senior firefighter, the other officer in the house, and the “overtime guy,” and you simply do not care because you don’t have to be in that day?

RELATED: The Dynamics of Change Leadership in the Fire Service | A Strong Command Presence Is Essential in All Incidents | Crisis and Leading When It Counts

Do you understand the process and details of why we do certain things in the firehouse and on the fireground to better train, manage, and lead? Or, do you simply do what is necessary to keep everyone off your back, to not ask your bosses questions, to never get involved with the “nuts and bolts” of the department, and then turn around and brag on social media or any unknowing listener about how you are the smartest guy on the job and everyone else is the problem?

As the officer, do you embrace your daily tasks in the firehouse and complete them diligently and thoroughly, taking initiative to complete expected goals like hose changing, ladder washing, window cleaning, waxing the apparatus, cutting grass, clearing the snow, reports, and other administrative paperwork? Or, do you employ every excuse in the book to your relief to explain why you simply did not do your job the day before and how much of a rush you are in to leave the firehouse, dumping your incomplete work on that officer?

Are You Sweating Right About Now?

Are you the kind of officer that aspires to learn the job; to get formally educated; or to speak with confidence, authority, and from experience to be taken seriously and provide direction and guidance? Or, do you really believe that simply showing up for work, going to a few fires, having fire academy certificates hanging on the wall, and wearing fire department shirts when off duty makes a good firefighter?

When you speak of incidents to which you have been, do you talk about what you have learned, what was effective and what was not, how decisions impacted safety, what could have been done differently to minimize risk, while appreciating others’ input, and passing on that knowledge and insight? Or, are you the braggart who amplifies, embellishes, adds to, and morphs stories into hero-worship tales; who speaks in the first-person of things that did not happen and that you were not a part of; who calls out those who performed poorly or made mistakes only to make yourself look better?

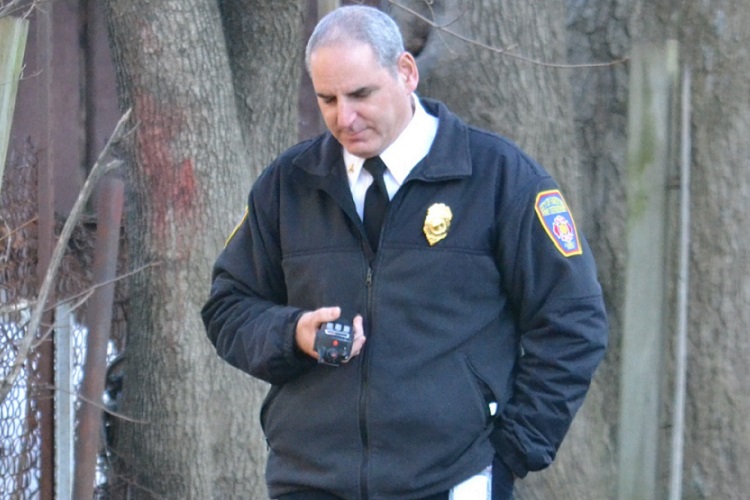

(1) Every opportunity to teach can be considered mentoring. (Photos by Pat Dooley.)

When a member of your crew comes to you with an issue, such as payroll, his uniform or gear, or other administrative problems that pop up in the firehouse, do you take it seriously and get to work on it with the same diligence and speed at which you would solve your own issues? Would you then report back to that crew member what you are doing and what will be done to fix this problem while also surveying your crew for anyone else having this same issue that you could collectively solve together? Or, are you just “barebones” managing the firehouse only to eat, sleep, watch TV, play video games, be the social media “butterfly,” and then go work overtime and do it all over again, having a personal philosophy that members are a bunch of crybabies and believe that you are not there to “babysit” them?

Did you join the fire service, take the oath seriously, work hard to learn and perform the duties, garner experience, set personal goals and achievements, and grow as a person; be a valuable part of your organization; share your knowledge to advance the mission and your department; and hand down a definitive contribution during your tenure? Or, did you take the job simply for the cool uniforms, the convenient schedule, the inherent power trips, and the status that comes with the image and identity of a firefighter only to further reinforce this with your big mouth and swelled head?

As an officer, do you engage the human element of the mission with humility, compassion, and empathy for what “they” (the victims and their families) may be going through? Or, are you arrogant, self-absorbed, pretentious, single-minded, preoccupied with your own selfishness, and you truly believe it is all about you?

As an officer, when a member of the public comes to you with a concern, a question, or a gripe, do you engage that person or group with enthusiasm, professionalism, institutional knowledge and leadership skills, listen to them, obtain their contact info, and make every attempt to resolve their problem or connect them with someone who will, then personally follow up to ensure their issues are being resolved? Or, are you flippant, evasive, uninterested, not willing to help, dismissive, intellectually unavailable, divert them to someone else who will just send them “chasing their tail,” or you just do not care?

As an officer, do you speak from first-hand involvement, tested perseverance, certified training, and acknowledge and appreciate that there is no substitute for experience? Or, did you just hear it from someone and repeat it like a parrot, learn it in some class, regurgitate it from an Internet video, or merely read it in a book?

Which Side Are YOU On?

Through my years of harvesting experiences at actual incidents and situations, I have encountered each of the aforementioned scenarios—in one form or another—and have garnered an appreciation and understanding of how to be effectual and goal oriented in personnel leadership beyond formal training and education. I am also proficient in what not to do and how not to interact with people, extracted primarily from individuals who simply did not have the best of intentions, the greatest attitude, or the most refined of personalities. One can learn equally from the bad as well as the good.

As an experienced fire officer, I am keenly aware of the lack of focus on the “right” way to handle human interactive situations and incidents in the fire service. I have observed great fireground commanders who were deficient when working with people, in a sense that it was taken for granted how to communicate effectively, including my less-than-desirable interactions, which were often the result of my approach to the situation. Fire academy training mainly consists of how to employ standardized manual-based theories and methods. Although well intentioned, these concepts often fall short when applied to the human element and, frequently, do not always match the situation or, worse, fail to deliver the desired outcome.

(2) Command presence is paramount to success.

Although I was competent in the practice of management, as a new officer, I was not equally prepared in the leadership of people. Because of this inadequacy, I was often compelled to learn “on the fly”—the hard way. Throughout my career, most issues requiring formal investigations and disciplinary actions that I was either involved with or had knowledge of were primarily personnel issues; policy infractions and contractual violations as opposed to operational deficiencies. These instances predominately involve a rift with someone else in the firehouse or an individual not behaving in a professional manner. Just like on the fireground, you must assess and stabilize the situation immediately. To do so effectively, it’s essential to identify the root cause to devise and execute a corrective action plan that is appropriate and satisfactory for all those involved. It is these experiences where a fire officer “makes his bones” and earns his keep, forging himself as a leader (not just on the fireground).

The Right Choices

The solution here is simplistic in theory but complex in execution. Many seasoned mechanics have said that the most abused and least maintained part of a car is the transmission. You can draw a direct parallel to the fire service, where the human interaction dynamic is the most used but least trained-on part of the job. The solution is to put forth a conscious effort, determine your communication and interaction skill set, and how you aspire to be received and perceived. To some, taking the right path comes naturally. For most, it requires a conscious effort, yet for some, it is simply beyond the scope of their capacity. The decision to do so and the subsequent communication process requires a solid foundation of the following intrinsic behaviors:

- Build soft skills. Spend time with your crews to understand and appreciate who they are as well as what they do (“walk the walk”). The most important thing an officer can do for his crews is to spend time with them (“The Golden Rule”).

- Preserve ethics and compassion. Be a beacon of professionalism; do not just say you are. Think of each situation as if you were on the other side of it and how you would expect to be treated.

- Practice coherent communication and critical thinking. Listen intently to others and speak with respect and dignity, no matter how irrational or illogical you think they may be. Deliver your message objectively with clarity and purpose. Explain and teach rather than lecture and confuse.

- Affirm your command presence. If you are in a leadership capacity, act accordingly! The calming, trusted, inspirational authoritarian figure will always get things done. Trustworthiness and confidence instilled in others when they need it most, in all situations, is paramount. I was inadvertently thrust into a situation in which I had to inform my assignment of firefighters of the line-of-duty death of one of our crew members immediately following the incident. There was no one else to do it—just me.

- Maintain an open mind. Believe it or not, you do not know everything; you can learn something new every day and from anyone, regardless of age, rank, or tenure. Everyone has something unique to offer. Always strive to be a student of the fire service.

- Lead by example. You are compelled by your duty to set a positive example for others to follow. Do not squander those opportunities. Provide guidance and direction, not ambiguity. Embrace time management and the ability to be flexible in your decisions and, most importantly, ensure your steadfast dependability. Leadership cannot exist without integrity.

- Select the proper action. Do the right thing every time, especially when no one is watching. Choose the course of action of which you would not be embarrassed if it was reported on the front page of the daily newspaper.

- Set the tone. Not everyone you encounter can think at the same level or speak at the same pace as you. Communicating takes patience and diligence.

- Demand accountability. Own your actions and those that serve under you and embrace your responsibilities.

- Project the proper demeanor. Although you may have to speak to individuals with a different style for each, ensure the message remains the same. You do not have to take yourself seriously to take the job seriously. Maintain a positive attitude, especially when being criticized, and be gracious because this can be a teachable event for you. Always maintain emotional maturity and intelligence; if you cannot control yourself, your input may be rendered baseless by others.

- Know the job inside and out. How can you effectively lead if you yourself don’t know? Learn the details and processes to understand the purpose. One of the fire officer’s duties is to facilitate success for subordinates to fulfill the mission.

- Develop people ready for anything. Prepare subordinates for any inevitability. Embrace initiative and engage it instead of avoiding it. Demonstrate definitive problem-solving skills, and the ability to acquire resources. Refine your ability to perform “under the gun.” I once trained my engine crew to be prepared for a bailout, an infrequently encountered event on the fireground. But just a day later, that same crew needed to bail out of a large fire while I was off duty. They called me at home and thanked me!

- Take a world view. Maintain the big picture concept of how decisions and actions affect things and people beyond your immediacy. Build value, trustworthiness, and validity for yourself and your people.

These attributes formulate a variety of “tools in your toolbox” from which to draw and fulfill your duties and responsibilities as an officer. This is the truest sense of mentorship and succession development—the ability to confer transformational leadership which, in turn, facilitates those that have learned from you the capacity to teach others. The ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu stated, “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach him how to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” Aptly applied, this lasting method of mentoring to produce the ability to succeed and thrive, even in your absence, is the ultimate goal: the lasting impact of enlightenment. But, what good is all of this if you consistently default back to bad habits and the path of least resistance like a slow leak in a tire. The objective of achieving and maintaining this status is complicated, but not out of reach; it just takes dedication, commitment, and perseverance.

Leadership can be taught, but the true learning and comprehension (wisdom) comes from experience. New firefighters are exposed to knowledge and understanding that is not garnered in manuals but instead through real-world incidents and actual events, thus producing—sometimes unwittingly—the fundamental principles of how to simultaneously lead and manage. The inherent human interaction dynamic of fire officer duties demands providing a clear set of expectations, behaviors, and desired outcomes with personnel. This provides a roadmap for effective leadership capable of achieving results in the firehouse and on the fireground. Without practical education and guidance through mentorship and succession development, those in leadership capacities are often cast into situations where they are charged with making critical decisions without the essential knowledge and skillsets. This lack of insight is often blamed for misinterpreting situations, which can have a ripple effect within the company and the entire shift. Often, excuses regarding the circumstances or being ill-prepared are made to justify negative outcomes. I have often focused my attention on the issue of properly leading and interacting with personnel through providing a practical understanding and appreciation for comprehension learned through experience and engagement; you know it as, “The stuff they do not teach you in school.”

Most firefighters know how to put out a fire, but it’s not the fancy tools or shiny trucks that get it done; it is the human factor. Great firefighters do not always equal great leaders, but like anything else we do, a balance of training, education, and experience are the keys to success. However, let me be clear—some individuals may never be a great teacher, communicator, or leader; a fact that must be accepted and, to some extent, expected. When these tools are appropriately applied using this enlightened mindset, fire officers have the capacity to critically evaluate their situation, select the appropriate leadership strategies and tactics, and accomplish the intended outcome. Always remember: systems and situations are managed, but people need to be led!

Leigh H. Shapiro, MS, retired as a member of the Hartford (CT) Fire Department after serving 28 years as a firefighter, lieutenant, captain, deputy chief/senior tour commander, and assistant chief/deputy director of emergency management. He has an AAS in fire science technology, a BS in public safety administration, and an MS in executive fire service leadership, as well as numerous State of Connecticut certifications including Fire Marshal. He now operates a fire service consulting firm and is an adjunct instructor, lectures on fire service leadership development, and has written for Fire Engineering. He can be contacted at bernenbush@comcast.net.

Leigh H. Shapiro, MS, retired as a member of the Hartford (CT) Fire Department after serving 28 years as a firefighter, lieutenant, captain, deputy chief/senior tour commander, and assistant chief/deputy director of emergency management. He has an AAS in fire science technology, a BS in public safety administration, and an MS in executive fire service leadership, as well as numerous State of Connecticut certifications including Fire Marshal. He now operates a fire service consulting firm and is an adjunct instructor, lectures on fire service leadership development, and has written for Fire Engineering. He can be contacted at bernenbush@comcast.net.