By Louis Sclafani

This past year while walking the exhibit floor of FDIC International, I made an effort to stop at every aerial apparatus manufacturer to talk aerials. My conversations reinforced my belief that firefighters have a number of misunderstandings about aerials. Let’s take a look at five of the most common.

Tip Loads

Probably the biggest misunderstanding has to do with loading firefighters onto the aerial device. Most firefighters have been taught the tip load of their truck. There is a minimum requirement for tip loads described in National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1901, Standard for Automotive Fire Apparatus. For aerial ladders, this minimum requirement is 250 pounds; for aerial platforms, it’s 750 pounds. This 250/750 standard is measured without any water in the waterway if so equipped. Again, these numbers are the minimum standard for aerials. Today, most manufacturers build heavy duty aerials that far exceed these minimum requirements. For example, it’s not uncommon to see aerial ladders with 500- or 750-pound tip loads. Depending on the model of your truck, your numbers will meet or likely exceed this minimum requirement. For our discussion, let’s say our truck has a tip load of 750 pounds.

The Aerial “Truck”: Ladders vs. Platforms

You head out to do some window rescue training. As the drill unfolds, you see there are multiple victims at the fifth-floor window. There are no obstructions, and this is well within the reach of your 100-foot aerial. You maneuver to the best spot, stabilize your truck, and then raise your device to the perfect position to rescue the victims. Two firefighters quickly ascend to assist the victims down. This drill is going perfectly; you will be out of here in no time.

One firefighter enters the window into the room and the other stays on the aerial to assist the victims down. After the first two victims are loaded onto the device, things seem to come to a stop. You listen in on the intercom and hear the discussion. The firefighter in the room is hesitant to load any more victims onto the ladder. He knows the rating for the ladder is 750 pounds. He counts three people already on the ladder. Using an average of 250 pounds per person, he says they are already at the device’s limit. Discussion goes back and forth until they decide to bring everyone down, two victims and one firefighter at a time. Ouch, you think, this is going to take longer than it should. Since there turned out to be five victims, this meant there were at least three trips up and down. That’s too much time and wasted energy.

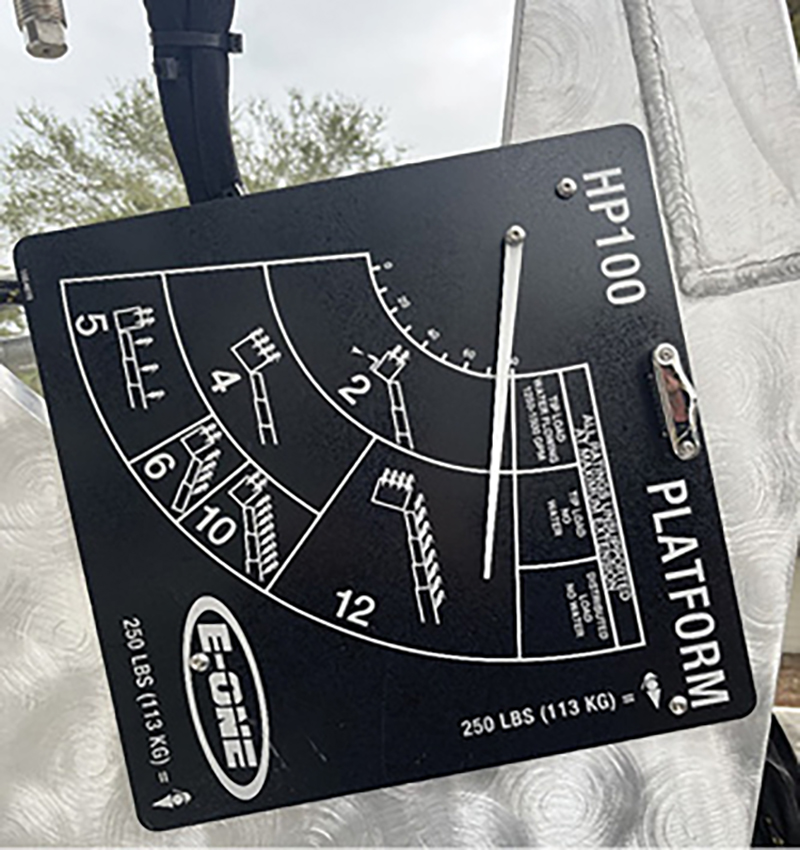

(1) An example of a pendulum-type load chart that shows a lower capacity while the aerial is in the horizontal position. (Photos by author unless otherwise noted.)

(2) As the aerial is raised, the chart moves and shows the increased capacity it can carry. The tip load stays the same but the total distributed load if fully elevated is 12 people or 3,000 pounds.

Since it is training, all meet after the drill to discuss loading the ladder. As it turns out, the firefighters were only familiar with the tip load we normally hear about and not the distributed load. You remind them that the tip load is just what the name implies, the weight at the tip, not the entire weight distributed over the length of the aerial. You show them the chart that’s near the turntable and also in the manual that shows the load numbers. The tip load number never changes, but as you raise or lower a device, the distributed load does change. You point out that the distributed load is less at lower elevations and more at higher elevations, where it can hold a greater weight. In fact, according to the chart in our particular truck, when fully extended and fully raised, it has a constant tip load of 750 pounds but a distributed load of 3,000 pounds. This is well above the 750 pounds most thought the device was only capable of supporting. Once all the firefighters understood this, they realized they could have sent the victims out one after the other, equally distributing them per their chart, and they could have all been out the window and on the ground in much less time than taking them out a couple at a time.

So, the load number we normally hear about is actually the maximum load allowed at the tip (or in the platform), at any elevation or any extension, if properly stabilized. If we distribute the weight (people) along the various sections of the ladder, we can hold more than just the tip rating. Remember, the weakest position of an aerial is when it is fully extended and at its lowest elevation. It only makes sense then, as we raise the device and it moves into a stronger position, that it would have the ability to carry more weight. Check your load chart!

Emergency Lowering

It’s Saturday morning, and you come in to start your shift. You pull the truck onto the ramp to complete your morning vehicle checks. All are good. The last thing to do is to exercise the aerial: It’s time to fully raise, extend, and rotate the device. With the device raised to 70º, you fully extend and then begin to rotate the aerial. With little warning, the whole truck shuts down. You’re not sure why, but you suspect a fuel contamination problem. The officer tells you to bed the aerial as he goes off to call the department mechanic. The new firefighter assigned to the truck looks confused. He asks, “How can you bed the aerial if the motor isn’t running?” You smile, take the new member under your wing, and show him.

When it comes to emergency lowering, there are essentially two options. The first is using the secondary hydraulic controls. They usually look like a set of handles with hydraulic lines running into and out of them. They are usually behind some panel somewhere and are not normally intended for everyday operator use. Your normal controls are an electric-over-hydraulic control valve. The ones behind the panel are direct hydraulic valves. They are typically used only when the electric portion of the controls you would regularly use stops working for some reason. If you remove the cover and look at the handles while someone else operates the regular electric-over-hydraulic controls, you will actually see these handles move simultaneously.

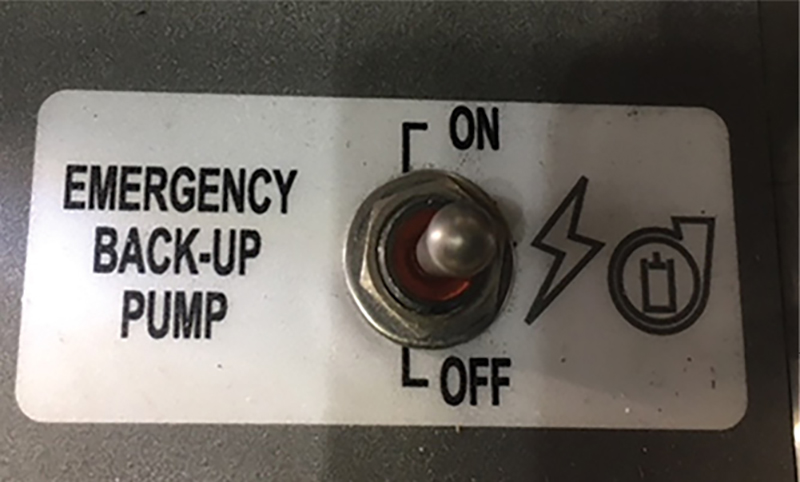

The second and more common option that is appropriate for our scenario is using the emergency or auxiliary hydraulic pump that was supplied on your truck and is intended for firefighter use. This pump uses electrical power to turn a secondary small hydraulic pump that charges the hydraulic system of the truck. So instead of the engine turning the hydraulic pump, it is turned by a small electrical motor similar to a starter motor. The only thing that has changed is the power source. The power take-off and transfer/diverter valves, if equipped, must be in their normal operating position for aerial use. It is recommended that you open the hydraulic valve you plan on using for aerial movement before turning on the electric pump so as not to build up excess pressure in the system.

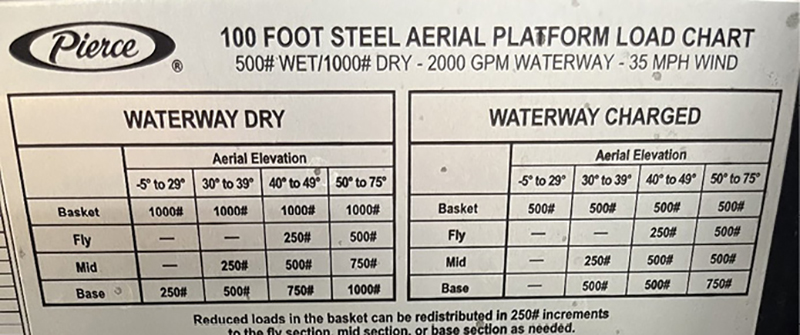

(3) This chart is typically found near the turntable for quick reference. It says the “Waterway Dry” tip load is a constant 1,000 pounds, but the total distributed load if fully elevated is 3,250 pounds.

(4) A typical emergency or auxiliary hydraulic switch. Be sure to check your manual to see how long these can be continuously run and the corresponding cool-down period.

These electric auxiliary pumps can overheat quickly. You should be familiar with the requirements of yours. Your manual may say it can run for five continuous minutes then need five minutes to cool down. It may say it can run for five continuous minutes then need 30 minutes to cool down, or something similar. Again, there is a wide variety of these systems, and you need to know exactly how yours works, especially the run time/cool-down time that yours calls for. Check your manual!

For some reason, it seems many aerial operators never touch this switch. But if you check your manual, you will likely find the manufacturer calls for these to be exercised regularly.

Green/Yellow/Red

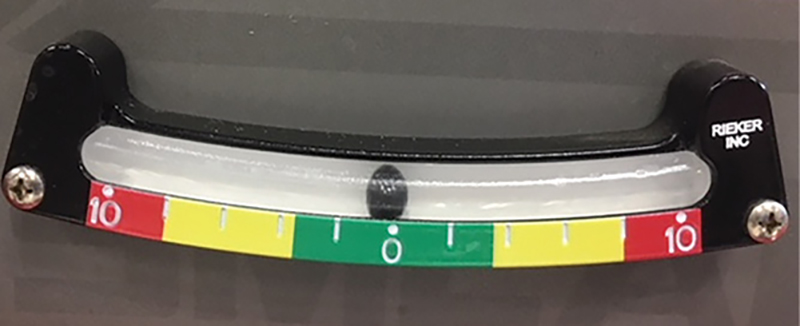

When it comes to warning signs, most people know that green is good and red is bad. But what exactly does yellow mean? It’s no different with aerial trucks.

You’re on the scene of a working fire at a large warehouse. The incident commander has decided to go defensive and has ordered your truck to set up an elevated master stream from your platform. The parking lot where you are setting up has a significant grade to it. As you gear up for the firefight, the apparatus operator positions and sets up the truck. As you and another firefighter are about to enter the platform, the operator tells you the best he could do was to set up with the level indicator in the yellow.

You hesitate and try to remember what that means again. Green is good, red is bad. Got it. But what does yellow mean again? You remember and tell the other firefighter to stay on the ground. No aerial operations for him tonight. Eyes wide and confused, the firefighter just watches as you go off to take care of the “big one.”

(5) This level indicator is in the green, indicating all is good. Red tells us, “Do Not Operate.” What does yellow mean?

(6) Damage to an aerial that has been reverse loaded would result in a failure similar to this. (Photo by Mark Rosetti/Demonracer2 Fire Photography.)

(7) The label may only say “Inlet,” but the rear valve can be used as either an inlet or a discharge.

The aerial operator proceeds to explain to the firefighter what just happened. This platform is rated to hold 500 pounds, or two firefighters, when flowing water. But when stabilized, the level indicator needs to be in the green. If it is in the red, he explains, he would have had to reposition. In this case, though, the best he could manage due to the grade of the parking lot was the level indicator being in the yellow.

So, what does yellow mean? It means that if operating in that range, all of the ladder loads are cut in half. In this case, that 500-pound load limit for the platform while flowing water becomes 250 pounds and only one firefighter is allowed in the platform.

Not every manufacturer uses the green/red/yellow level indicator. In fact, as I look at new apparatus deliveries, I am seeing less and less of it and more and more of simple green/red. It’s probably just as well, as it is one of the things commonly misunderstood about aerials.

Supported or Unsupported

As a young firefighter, I was lucky enough to sit in on an FDIC class on building construction by the late Francis L. Brannigan. He had a passion for firefighter safety as it related to building construction. His book Building Construction for the Fire Service is still used today. The one line I heard him repeat several times and that is permanently ingrained into my memory is, “A truss is a truss is a truss.” He would then go on to explain how one chord of a truss is being stressed under tension, and the other chord of the truss is being stressed under compression. If you damaged any part of the truss or if you were to reverse load these stressors, resulting in more stress on the chord designed to be under tension and less on the chord designed for compression, you would have a catastrophic truss failure.

So, why is this building construction lesson in a discussion about aerials? Most aerials are constructed using the truss method. Remember, a truss is a truss is a truss, regardless of whether it’s in a building or part of an aerial device. Aerials are designed with the bottom chord being under compression and the top chord under tension. So, to maintain compression on that bottom chord and tension on the top chord, the tip or platform is never supposed to be lowered onto anything such as the ground, roofline, windowsill, or parapet. It should be kept in what we call a cantilevered, or unsupported, position. This is why, when we raise our aerial to our target, we generally keep it four to six inches away. This way, when we climb the aerial and it starts to deflect (bounce), we don’t end up reverse loading our aerial (truss). To be clear, just touching the building or ground with your aerial is one thing. Fully resting or pushing down is another.

Inlet or Discharge

There is one way you can use a quint that isn’t well understood. A quint is essentially a pumper with an aerial device attached. It can be used as a pumper or as an aerial. Most, if not all, quints have prepiped waterways. One of the advantages of a quint is that it can supply its own waterway and master stream from its own pump. Additionally, at the tip of most quints there is commonly found a 2½-inch discharge that can be used for an elevated external standpipe operation. Crews with quints that have this 2½-inch option know that to use it they must charge the waterway but close a secondary valve so the master stream doesn’t flow at the same time. This procedure is fairly well understood.

Now let’s look at what’s not so well understood. In the back of most rear-mounted quints, there is usually an inlet valve. Attaching a supply line to this inlet will only charge your prepiped waterway. It will not charge your pump, as there is a clapper-type valve that will block the water from flowing in that direction. But this valve is not only an inlet, it is also a discharge. This is commonly misunderstood by firefighters.

Once this is understood, firefighters realize they have a large-diameter discharge available to them if the quint is needed not as an aerial but as a pumper, and they could pump large volumes of water through large-diameter hose. The quint operator simply needs to close that secondary valve like he would if it were an elevated external standpipe operation, attach the appropriate appliance to the valve on the back of the truck, and pump large volumes of water out the rear of the truck.

Since aerials are the most expensive and complicated pieces of equipment in most fire departments’ inventory, it’s important that we know how to use them properly and to their full potential. Review your truck’s manual, then get out there and train. It’s best to learn these things on the drill ground so you can use them later on the fireground.

LOUIS SCLAFANI has been in the fire service for 40 years. Now retired, he served for 30 years with the Pinellas Park (FL) Fire Department. He spent 19 years as the shift district chief and three years as the training chief. He has an associate of science degree in fire administration from St. Petersburg College and is the lead aerial instructor with St. Petersburg College.