By Michael J. Barakey

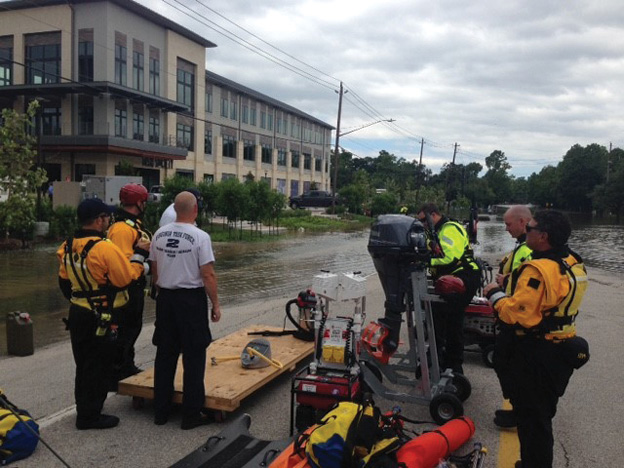

Virginia Task Force 2 (VA-TF2), based in Virginia Beach, deployed to support the search and rescue efforts prior to Hurricanes Irma and Maria making landfall in the United States Virgin Islands (USVI) and Puerto Rico. VA-TF2 had been operating in Texas following Hurricane Harvey, supporting 19 members in South Texas and the Houston Metropolitan area. The TF operated as a Mission Ready Package-Water (MRP-W) and was supporting the incident support team (IST). It was actively performing search and rescue operations in the water environment when it was requested to prepare for a possible mission to Puerto Rico. Some key pieces of the TF’s cache, most notably pickup trucks and water rescue assets, were committed to the Harvey deployment. In Texas, VA-TF2 had evacuated 590 people and 20 companion animals to safety, performed multiple welfare checks of civilians who decided to shelter in place, and assisted Houston Public Utilities with access to a pump station and the Houston Fire Department with mitigating gas leaks in residences by boat.

(1) VA-TF2 searching damaged structures in St. Thomas. (Photos courtesy of Virginia Task Force 2.)

Activation for Hurricane Irma

On September 4, VA-TF2 was activated at midnight to stage in San Juan, Puerto Rico, two days prior to Irma’s landfall. At the time of activation, Hurricane Irma was a Category 3 storm and was quickly gaining strength. The forecast had the eye passing near the northern portion of the Leeward Islands, to include the USVI and Puerto Rico on Wednesday, September 6, at 1400 hours.

The Logistics component worked overnight to palletize the Type 1 cache and six vehicles for air transport by a C-5 and C-17 from Norfolk Naval Base’s AMC terminal to San Juan. The cache was packaged for “over the ground” transportation and had to be palletized for airlift by military cargo plane. This necessitated building and weighing the pallets and preparing the cache’s hazardous materials for military air shipment—i.e., Hazdec. While the Logistics team was preparing the cache, the TF’s command and general staff prepared the 45-member team (Type III) with 10 ground support personnel for medical checks and processing. By 0100 hours, the cache was sorted and loaded onto tractor-trailers for transport to the AMC. The weapons of mass destruction and hazmat portions of the cache were removed. This decreased the number of pallets and ensured the equipment necessary for the mission would be delivered to San Juan. The TF’s cache was to be sent to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Caribbean Distribution Center (DC) in South San Juan about 20 miles south of the airport. The incident support team (IST) was to arrive in San Juan before the arrival of the TF and the cache to conduct needs assessments, planning, and assess logistical considerations.

As the team was arriving at the point of departure, the airframes were secured. A C-5 and C-17 were assigned to transport the pallets, trucks, and team members to San Juan. The C-5 arrived first, followed shortly after by the C-17. The plan was to load the C-5 with the four small vehicles, two straight box trucks, and a pallet of gear. The C-17 would be loaded after the C-5 with 14 pallets containing the cache. At 1800 hours, all the members had passed the medical screening and were prepared for departure to the AMC terminal. The TF leaders briefed the team at 1830 hours. The TF arrived at the AMC terminal at 1945 hours. The original plan was to lift off at 2230 hours with the C-5 and at 0030 hours the next day with the C-17. That would have put the C-5 into San Juan at 0130 hours and the C-17 in at 0330 hours on September 5.

Prior to loading any equipment or vehicles onto the C-5, the air crew notified the TF’s Logistics team manager that the air crew would “time out” and could not perform the mission that evening. The air crew needed rest and was transferred to a local hotel to meet their required down time. A K-loader put the 14 pallets on the C-17. There was space to take only six TF members. With Hurricane Irma less than 36 hours away from Puerto Rico, it was decided that we would get the cache and the six team members into San Juan as planned so that the cache could be moved during the daylight hours in advance of Hurricane Irma’s landfall. The C-5 with the remainder of the TF members would be in San Juan on Tuesday, September 5.

September 5: One Day Before Landfall

The C-17 was loaded at 0015 hours and lifted off at 0105 hours. As the aircraft climbed to 4,000 feet, the air crew notified the TF leaders that an air manifold in the right wing had developed a leak, which prevented the engine from being able to de-ice once at altitude. The C-17 was diverted to Joint Base Charleston and landed without issue at 0230 hours. The six members deplaned, and the cache was moved to another C-17 that was already at Joint Base Charleston.

At 0530 hours, the six members loaded a bus and moved to the new C-17. The air crew had moved the 14 pallets, and the flight crew was awaiting approval of the final flight plan to move the cache and the members to San Juan. At 0730 hours, the C-17 lifted off from Joint Base Charleston with a two-hour, 45-minute estimated time to arrival to San Juan. The C-17 arrived at San Juan Louis Munoz Manor International (SJU) at 1015 hours. The TF deplaned to high humidity and heavy rain from the leading rain bands from Hurricane Irma. A representative from the DC greeted the TF and arranged for the pallets to be transported to the DC for safe housing while Hurricane Irma passed.

(2) VA-TF2 working in Katy, Texas, following Hurricane Harvey.

The remainder of the TF still in the continental United States conducted a manager’s meeting at 0800 hours. By 0830 hours, the remainder of the TF was at the AMC terminal and prepared to load the C-5 to San Juan. Because of Hurricane Irma’s path, the window to move the TF and the remainder of the cache and trucks was closing. The TF leaders, plans, and component managers participated in conference calls with FEMA Region II and the IST throughout the day.

In San Juan, it took four hours to remove the 14 pallets by forklift and place them on the airfield. Dunnage had to be delivered so that the pallets could be placed on the tarmac and then moved to awaiting flatbed trucks as they arrived. The C-17 needed to be airborne by 1400 hours. The TF learned there was room for only nine pallets at the DC; once all 14 were unloaded, the Puerto Rico Fire Department’s Search and Rescue (PUS&R) TF, the Puerto Rico Police Department, and several private vendors used flatbed trucks and rollback wreckers to move the nine pallets to the DC. The trucks and pallets moved in a caravan with police escort at 1700 hours.

The C-5 landed at 1852 hours. Once the two straight box trucks were driven off the C-5, the five remaining pallets were broken down and the cache was loaded on those two trucks. The remaining members were transported to the base of operations (BoO) by bus and secured for the evening.

Once the TF’s command staff was reunited at the BoO, the IST Operations chief, safety officer, and plans manager conducted a briefing. The Operations chief provided the incident objectives for the next operational period: (1) identify and divide the TF to perform damage assessment on the ground or by air; (2) develop a recon plan; (3) consider air frame insertion into the USVI (St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix); and (4) remain safe as Hurricane Irma passes the island. The TF leaders and plans managers acquired maps of Puerto Rico and the surrounding islands, flood and water surge maps, and global positioning system and geographic information system (GPS/GIS) applications. The TF’s structural engineer, safety officer, and hazmat team leader provided the command staff with a site safety plan for the BoO. The TF’s team physician and medical team manager provided a medical plan. These documents were important because the IST had limited personnel in San Juan at that time and landfall was the following day. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) provided force protection; the agents began to arrive by 1830 hours. Without knowing the exact direction of Hurricane Irma, the IST and the TF prepared for missions in Puerto Rico and the USVI. The IST briefed the TF leaders at 2100 hours. With all the preparation completed, the TF could go operational immediately after Hurricane Irma passed.

September 6: Day of Landfall

Hurricane Irma passed the USVI as a Category 5 with winds of 185 miles per hour. The storm was one of the strongest hurricanes ever recorded. With landfall imminent in Puerto Rico, the IST command and general staff briefed the TF leaders at 0700 hours. Hurricane Irma was six to eight hours from San Juan. Work at the DC was limited to the TF’s logistics members, and they were required to be secure in the BoO by 1200 noon. Mapping of the island of Puerto Rico and the USVI continued. The goal was to perform recon by air and ground once the storm passed. Hurricane Irma passed just to the north of Puerto Rico and delivered heavy rains and strong winds. The height of the storm was between 1600 and 2000 hours. Since the power was out on the island, recon commenced with first light the following day.

September 7: Day 1 After Landfall

After a 0700 hours briefing, the weather had improved. The TF performed a windshield assessment of the east side of Puerto Rico to identify damage, need for search and rescue, and landing zones for rotor-wing aircraft. The recon team traveled with force protection to Roosevelt Roads. The mission turned up very little damage to the island; power outages were throughout the east side, and power lines were down in many areas. While the TF was surveying the east side of the island, the FBI convoyed in San Juan and made it to the cache’s location at the DC. The FBI’s recon team reported that the roads were passable but trees were down and light poles were on the ground. The TF’s structural engineer, search team manager, rescue team manager, and tech information specialist went on a recon mission with the PUS&R Rescue Team manager.

Logistics sent members to the DC to evaluate and unpack the cache for missions in Puerto Rico and the USVI. Communications were limited to satellite phones using the TF’s Iridiums and MSAT-G2s. The areas identified for possible forward movement were St. Thomas, St. John, St. Croix, and the mountainous areas of Puerto Rico. Human intelligence became valuable as the recon teams traveled the island. All the information learned during recon was forwarded to the IST. While the recon team traveled the island, landing zones were identified to receive inbound aircraft or to safely move personnel to the USVI.

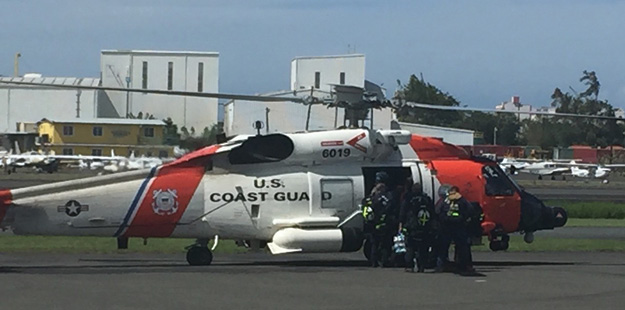

(3) Members of VA-TF2 load a Coast Guard helicopter for St. Thomas.

The IST was receiving intelligence from the USVI. St. Thomas reported that the roof was off a hospital and the power was out on the island. Initial damage assessments of the critical infrastructure on the island were just starting to be conducted. Airframes were being prioritized. Once the weather calmed and the airframes became available, the TF would be in the queue to send search and rescue capabilities to St. Thomas. The FEMA Region II director was working with the IST to increase the number of search and rescue assets in San Juan. Fifteen additional members of VA-TF2 were activated to increase the number of TF members to 60.

Local emergency managers in the St. Thomas Emergency Operations Center (EOC) were identifying and assigning missions for St. Thomas and St. John. Social media from the island was nonexistent. Intelligence was limited to FBI agents on St. Thomas providing information back to the IST. The IST operations chief elected to push US&R capabilities to St. Thomas to perform hasty and targeted searches, wide-area search, and light rescue work. The goal was to get the TF to St. Thomas by rotor aircraft because the airport was closed to fixed-wing flights. The IST was developing the “rules of engagement” for the members being inserted into St. Thomas and St. John.

The Caribbean Deployment

The IST transitioned the system’s focus from Puerto Rico to St. Thomas and St. John after the recon teams verified there was no immediate need for search and rescue operations on Puerto Rico. The priority became search and rescue in the USVI. Two divisions were established: St. Thomas and St. John. The immediate goal was to get a search and rescue element forward to St. Thomas and then to St. John. The Logistics Team manager developed a plan to get the TF’s cache to St. Thomas. Anticipating the amount of search and rescue work to be performed in the USVI, the IST increased the number of TFs in the theater. It ordered two additional Type 1 teams, MRP-Canine live find, MRP-Canine for human remains, and the IST Central Logistics cache.

Transportation options from San Juan to the USVI were few. The only way to get to St. Thomas was by air. The Port of San Juan and the Port of St. Thomas were closed following Hurricane Irma’s landfall in the region. Mission assignments were prioritized for operational periods of 24 to 48 hours, unsupported. The IST desired hasty and targeted searches, with primary searches based on the intelligence being received from the St. Thomas EOC. Each island would require a Forward Operations Base (FOB). For each air package developed, the IST’s air boss required a crew manifest with each TF member’s name and weight and the weight of the equipment.

The U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) worked to open the port and the shipping channels. Until the port was opened, the Logistics team manager could not secure a ship or ferry to move the TF’s cache to St. Thomas. The runway at Cyril E. King International Airport (STT) was deemed clear for missions, yet since STT’s air traffic control was down, no fixed-wing missions could be accomplished.

The first helicopter became available to take personnel to St. Thomas at 1145 hours. It was a USCG Jayhawk UH-60. Missions were flown out of Isle Grande Airport (SIG) in San Juan. IST placed a member in the USCG command center at Sector San Juan to coordinate air transportation. The next flight became available at 1400 hours.

By day’s end, 11 members from VA-TF2 made it to St. Thomas. The TF leaders secured shelter with the FBI at their San Juan building. Hurricane Jose was 36 to 48 hours away from making landfall in St. Thomas. The TF leaders needed to secure suitable shelter for the TF because Hurricane Jose was a Category 3 storm and was forecasted to pass near the USVI. The TF leaders contacted the leadership at the St. Thomas EOC; both parties agreed to start operations at first light the following morning.

September 8: Day 2 After Landfall

St. Thomas Division. Operations began in the morning. The TF performed hasty and targeted searches six miles inland in the southeast part of the island. The St. Thomas fire chief provided the missions. The TF leaders divided the TF into three three-person teams with FBI agents as force protection. Operations continued throughout the day. The TF made numerous contacts with the locals and cleared moderately to severely damaged structures. By evening, the TF had 22 members on St. Thomas with two straight trucks and a pickup truck, which arrived by ferry.

A portion of the cache was moved to STT from the port. The FBI decided the number of TF personnel had exceeded the footprint for an FOB at its office; it was jointly decided to move the TF to the Marriott on the south side of the island. Although the Marriott was severely damaged, the property had generator power and running water.

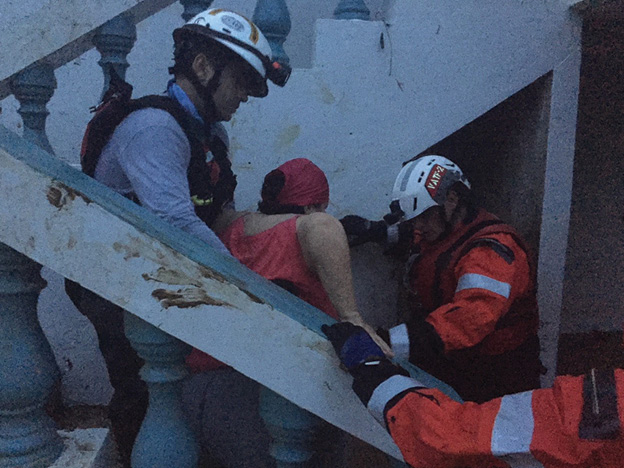

(4) VA-TF2 makes a rescue in Toa Baja.

St. John Division. The IST prioritized mission sets for the St. John Division as intelligence from the EOC in St. Thomas reported the need for search and rescue teams in St. John. TF members were flown from San Juan to St. John on Customs Border Patrol (CBP) and USCG helicopters. As the TF arrived on St. John, logistical support was dependent on the TF leaders building relationships with the National Park Service (NPS). It took 45 minutes one way to fly personnel to St. John. After being dropped in a school baseball field in Cruz Bay, the TF members had only the web gear they were wearing and what was in their 72-hour bag. The TF leaders acquired five vehicles from the NPS to move the team around the mountainous island.

Hurricane Irma had devastated the island. All the aboveground utilities were on the ground. The island was brown in color; the intense winds had stripped all the leaves. The branches of the trees and cactus were all severed about 12 feet above the ground. All wood-frame buildings were extremely damaged or destroyed. The TF leaders contacted the NPS incident commander and established an FOB in the NPS Visitor’s Center in Cruz Bay. With little to no information known about the path or strength of Hurricane Jose and no Internet or cell service available on St. John, the TF leaders developed a plan to secure the TF when Hurricane Jose arrived. The forecast provided to the TF leaders by the IST was that Category 1 winds and heavy rain would arrive by 1400 hours the following day. Shelter became a priority on the devastated island because few structures were intact.

Search and rescue efforts prior to the arrival of the TF were limited to neighbors helping neighbors and the island’s firefighters and emergency medical services (EMS) providers performing limited missions. Intelligence gathered after meeting with the fire chief and the EMS chief was prioritized into areas that were completely devastated. These areas were mapped, and the TF leaders briefed the TF. Coral Bay, Fish Bay, Chocolate Hole, Hurricane Hole, and Upper Carolina were the priorities.

September 9: Day 3 After Landfall

St. Thomas Division. Because communications were limited to the MSTAT-G2 satellite phone, with no dedicated air support and no suitable FOB, the IST pulled the TF off St. Thomas. Twelve of the 22 TF members went to the airport and were airlifted back to San Juan by helicopter. The 12 remaining members made it to the airport but never got an airframe off the island. The FBI took the 12 remaining members to the FBI compound in downtown St. Thomas; they continued to perform targeted searches in accordance with missions from the St. Thomas EOC and the IST.

(5) VA-TF2 and the Kentucky Air National Guard perform a basket hoist in Coral Bay, St. John.

St. John Division. The TFL assigned the entire team to the most devastated area on St. John, Coral Bay. It took the TF more than one hour to travel five miles from Cruz Bay to Coral Bay because the only road, Center Line Drive, was covered by down trees and down power lines. The TF found that almost every home in Coral Bay was heavily damaged or destroyed. Hundreds of boats in Hurricane Hole were pushed onto the road. The fire station in Coral Bay was destroyed.

The TF performed hasty and targeted searches in Coral Bay. The members began at the bay and worked into the mountains and switchbacks that overlooked the bay. As the TF worked in a remote switchback, locals reported two elderly people were trapped and in need of rescue at the top of the switchback. It took more than 45 minutes to transverse the narrow road that was unpassable by motor vehicles. The TF had to cut their way through the debris to the elderly couple’s destroyed home. Once the TF assessed the elderly couple, it was clear that the couple could not walk out and no vehicles could make it up the steep mountainside to remove them.

Unrelated to the TF’s mission, a Kentucky Air National Guard helicopter had landed in a school ball field in Coral Bay.

The TF leaders requested the UH-60 to hoist the elderly couple off the mountainside. The TF leaders communicated and coordinated the rescue between the air boss and the personnel on the switchback. GPS coordinates were called down and provided to the air boss. Using that information and markers placed by the TF, the pilot flew the UH-60 to the area above the couple’s home. As the helicopter hovered above the home, two pararescue jumpers were lowered to the home. The couple was loaded in the basket and hoisted to the helicopter.

In all, the Kentucky Air National Guard evacuated four citizens with medical issues from Coral Bay to St. Croix: the elderly couple, an elderly blind man with no medicine, and a liver failure patient. The TF finished working the Coral Bay area and then moved to the mountains in Upper Carolina. The terrain was not accessible by vehicles. The TF members had to walk steep elevations and clear blocked roadways in extremely hot conditions to access the people on the mountainside.

While the TF performed search and rescue operations in Coral Bay, the FOB became the NPS’s command post, leading TF leaders to secure a suitable FOB for the TF. Hurricane Jose was hours away from the island. Without shelter, the TF leaders met with the general manager for the Canneel Bay Resort. Hurricane Irma had heavily damaged the resort, located north of Cruz Bay. The resort’s Human Resources building was concrete and suitable to serve as the FOB despite its damages from Hurricane Irma. Two more members, a structural engineer and the plans team manager, arrived to support the TF.

September 10: Day 4 After Landfall

St. Thomas Division. The IST diverted the TF to continue hasty and targeted searches with the 12 TF members who remained on the island. The north side of the island area was designated for hasty and targeted searches. As the day continued, targets that were deemed “credible” were searched and cleared. In the late evening, all but one TF member was loaded onto two CBP helicopters for transportation back to San Juan.

St. John Division. The TF leaders divided the island into North and South divisions. The operational period called for search and rescue operations in Cinnamon Bay to the north and Fish Bay to the south. The goal was to perform and mark primary searches on all buildings that were destroyed or for which a survivable void was not present. Because of the number of destroyed and heavily damaged structures in the targeted divisions and the heat and humidity, the IST brought in more personnel from VA-TF2.

At 1400 hours, the TFL ordered both divisions back to the St. John FOB because the FBI agents providing force protection for the TF was being airlifted off St. John and reassigned to St. Thomas. Since the force protection was reassigned and could not resupply the TF with MREs and water, the IST removed all personnel from St. John.

The TF returned to the Cruz Bay harbor and took a 45-minute ferry ride to Red Hook Marina in St. Thomas. The 22 members were moved from Red Hook to STT and were flown by a C-17 with the last remaining member from the St. Thomas Division at 2100 hours. By 2200 hours, all the TF members were back at the BoO in San Juan.

September 11: Day 5 After Landfall

This was the 16th anniversary of the terrorist attacks on the United States. At the BoO, there were more than 250 FEMA US&R members assigned to the IST (from many TFs) and search and rescue teams representing NY-TF1, VA-TF 1, VA-TF2, TX-TF1, CA-TF6, and MA-TF1. Everyone paused for a moment of silence while VA-TF2’s Medical Specialist Israel Medina sang the National Anthem. Operations on St. John and St. Thomas were transitioned to VA-TF1. Prior to being airlifted to St. Thomas and St. John, VA-TF1’s leaders were provided pass down and human intelligence from VA-TF2’s leaders, physician, and rescue team manager.

September 12-16: Days 6-10 After Landfall

The members received rehabilitation, rested, and performed documentation over these operational periods. With VA-TF1 working St. Thomas and St. John, the members of VA-TF2 were able to download the many tracks and ironsites (predesignated symbols used to mark buildings, rescues, and damages) to their GPS units and send the files to the IST. The members went through medical checks and rehabbed their equipment. On the afternoon of September 15, the TF moved to SJU for a return trip back to the airport. The TF arrived back at the airport in the early morning hours of Saturday, September 16. The TF’s cache was palletized and readied for transport by air back to Naval Station Norfolk.

While operating in Puerto Rico, St. Thomas, and St. John, VA-TF2 rescued four people, evacuated 16 people, searched 342 failed or destroyed structures, and made 1,543 contacts.

Activation for Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico

September 18: Two Days Before Landfall

The TF’s cache was still in San Juan with two Logistics team members who remained there. FEMA worked with the Logistics team members to return the cache and vehicles on a C-5 and C-17, but as Hurricane Maria continued toward Puerto Rico, the program office decided to keep the cache in San Juan. With the Type I cache already in San Juan, FEMA activated VA-TF2 for a Type 1 deployment (70 personnel, 10 ground support, and five canines) at 0600 hours. By 0900 hours, the TF was checked in. Hurricane Maria was the fourth major hurricane of the season and was forecasted to affect the same areas that were hit by Hurricane Irma as a Category 4 or Category 5 storm with a projected landfall of Wednesday, September 20.

At 1430 hours, the program office indicated an aircraft would be assigned within an hour. The TF leaders received notice at 1500 hours that the aircraft would be at the airport at 1630 hours. The plane took off at 1825 hours and arrived in San Juan at 2142 hours. By the time the TF arrived at the BoO in San Juan, Hurricane Maria was a Category 5 storm.

Tuesday, September 19: One Day Before Landfall

The TF leaders met with the IST, and VA-TF2 was assigned the Puerto Rico Division. FL-TF2 deployed a Type IV and MRP-Canine with 27 personnel and was assigned to embed with VA-TF2. In all, VA-TF2’s Type 1 cache would support 107 personnel and seven canines.

At the morning operations briefing, the IST leader informed the TF that Hurricane Maria was a Category 5 storm. It was forecasted to be “catastrophic” if Puerto Rico took a direct hit. The IST leader’s direction was for the TFs to prepare for landfall and to be able to perform search and rescue operations after Hurricane Maria moved past the island. Hurricane conditions would arrive in the evening hours and be sustained through Thursday morning.

VA-TF2 and FL-TF2’s leaders planned for missions once Hurricane Maria had passed the island. The TF leaders developed a MRP-W, search and rescue packages for ground and air missions in Puerto Rico, Vieques, and Culebra. Different packages were developed to meet any scenario or mission requested. As the day continued, the Plans team identified areas that were high hazard and had high probability of needing search and rescue operations following landfall.

Wednesday, September 20: Day of Landfall

The BoO rocked as the winds continued to increase throughout the early morning. Hurricane Maria made landfall as a Category 4 storm; the damage was described as severe to catastrophic. At 0600 hours, after the IST’s and TF’s structural engineers evaluated the BoO, all TF personnel were moved to interior hallways and the core of the BoO.

At 1000 hours, the IST briefed the TF leaders. Direction was given to initiate recon on the third floor to determine the level of damage to the BoO. There was standing water throughout the BoO. The TF received approval from the IST and the BoO’s general manager to remove the carpet in the TF’s command post (CP). The CP was reopened at 1300 hours, and the TF initiated a systematic recon of the entire BoO to determine the level and severity of damage.

The IST directed all the TFs in the BoO to “muck and gut” the carpet, stairwells, hallways, and rooms that were saturated by water. A welfare check occurred off the BoO’s grounds while the TF’s structural engineers evaluated the BoO’s roof as water was freely running into the stairwells and elevator shafts. Trees and debris were removed so missions could begin once the winds subsided.

At the evening’s operational briefing, the TF received missions to perform recon in east, west, and south Puerto Rico by ground. If water assets were needed, the recon teams would call back to the CP and request the MRP-W. Three 12-member teams were established. Each team brought light rescue tools and chain saws. The MRP-W included two inflatable boats on a trailer and life safety suits and equipment for working in the urban water environment.

Thursday, September 21: Day 1 After Landfall

The TF deployed three teams. The operational period began at 0800 hours with a list of targets received from the IST and prioritized by the Plans team manager. Intelligence from PUS&R identified a shelter with more than 600 people who were trapped by rising waters. PUS&R reported roads were washed out, bridges were not passable, and communications including cell service and texting were nonexistent on the entire island. This placed emphasis on the recon teams to gather human intelligence because normal means of communication (911, for example) were not available to the citizens of Puerto Rico.

Situation reports were provided to the CP every hour the three teams moved in their respective divisions. Intelligence continued to report that the town of Toa Baja was under water. The West Division supervisor confirmed people were on the roofs needing rescue.

The TF’s MRP-W was deployed from the BoO. The West Division supervisor confirmed that the locals were reporting one person deceased with nine people on roofs. The MRP-W launched two boats. The high-water vehicle arrived; the TF leaders prioritized the rescues. Operations took four hours.

(6) VA-TF2’s MRP-W prepared to respond anywhere in Puerto Rico.

One person was confirmed deceased, and the TF rescued an elderly male and female. The TF leader working the MRP-W also worked the Houston, Texas, flooding. He remarked that Toa Baja appeared to be another Houston. The West Division and the MRP-W delivered one patient to local EMS and rescued two children and two adults.

The Central Division traveled to the south to perform targeted searches in Ponce and Caguas. The roads were mostly passable with standing water on most roads and wires and trees down. Structures in the mountain areas appeared to have moderate damage, but the roads were in the switchbacks and higher elevations.

East Division traveled to Loiza, which was reported to be flooded. The East Division supervisor reported six inches of water in the town. We learned from the locals in Loiza that the water was all the way up to the roofs but it quickly receded. The East Division completed the targeted searches and returned to the BoO.

September 22: Day 2 After Landfall

The mission assignments remained the same as for the previous operational period. The MRP-W returned to Toa Baja. The East Division became the San Juan Division, and the Central and West Divisions pushed toward their targets. Intelligence continued to come into the TF leaders from the IST. More targeted missions were sent to the MRP-W in Toa Baja. Intelligence from the PUS&R liaison reported areas with human remains and people needing rescue in Toa Baja and Vega Baja. The mayor of Toa Baja reported that more than 450 homes were under water and the locals had no capabilities or resources to perform rescue operations in the water environment. The water receded in many areas of Toa Baja, so the TF searched on foot there. The locals identified to the TF a structure with eight people deceased from floodwaters. The TF leaders attended meetings with the local government to determine the level of operations.

(7) The flooding in Toa Baja.

San Juan Division completed targeted searches in high-risk facilities to include nursing homes, hospitals, and shelters. FL-TF2 rescued one person and evacuated two people. The West Division traveled to Isabella and Aguadilla; the supervisor contacted Isabella’s mayor. The mayor stated that there had been no contact with many areas since the storm. The TF performed search and rescue operations in Isabella at the request of the mayor. In Aguadilla, the TF confirmed two police officers died when they were swept away by floodwaters while crossing the Culebrinas River in a vehicle.

The West Division supervisor reported that Guajataca Dam was in danger of failing. VA-TF2 structural engineers were sent to the dam with the IST to determine if the dam was in danger of failing and if evacuations were necessary. The two engineers worked all day to assess, mark, and monitor the damaged spilway.

September 23: Day 3 After Landfall

For this operational period, the IST renamed the three divisions East, Central, and West. VA-TF1 and FL-TF1 worked the East Division. VA-TF 2 and FL-TF 2 worked the Central Division. The MRP-W continued to work in Toa Baja as part of the Central Division. VA-TF2 worked the West Division.

As the TF traveled, the citizens of Puerto Rico were seeking commodities. The aboveground utilities were mostly down and were being cleared to allow travel on the primary and secondary roads. Lines for fuel, the bank, and grocery stores were long. Commodity escorts were occurring, and the police were visible and maintaining order at each fuel station.

The TF met the mayors or government leaders in San German, Cabo Rojo, Mayaguez, and Quebradillas. Each EOC and emergency manager requested fuel, water, and communications. A target was assigned in Quebradillas, but the TF was unable to complete the mission because of 10 feet of water on the road. One deceased was marked in the Mayaguez area after a landslide overtook an excavator.

Water rescue operations were completed in Vaga Baja and Toa Baja. No boats were used because the water had receded. All hasty and targets searches occurred on foot or using high-water vehicles. All structures searched were marked with FEMA US&R ironsites (markings on structures that indicate they were searched, were uninhabitable, amd so on). The local government indicated their needs were water, fuel, and communications.

September 24: Day 4 After Landfall

MA-TF1 transitioned into the West Division and worked with VA-TF2 for the operational period. The TF went back to the EOC in Querbradillas to complete the mission from the previous operational period. The emergency manager had acquired a high-water vehicle and front loaders to clear the road and path to the target. The location was confirmed after taking a high-water vehicle to the top of the dam and then walking to the basin and up the other side with stokes baskets, tools, medical equipment, and local EMS. The TF found the patient in a home on the top of the mountain on the other side of the spillway. The TF contacted the family; they did not want the elderly patient to be moved. It was agreed that local EMS from Isabella would respond from the opposite direction to provide care. While performing that mission, an elderly male passed away in his home. That death was not related to the hurricane. The TF supported the local EMS providers as the patient passed away.

(8) VA-TF2’s structural engineers evaluated the Guajataca Dam.

The mission was completed, and the TF returned to the Querbradillas EOC. After a debriefing with the emergency manager, the TF went to Aguadilla to visit with the police chief. The TF provided condolences for the passing of the two police officers who died. The police chief stated that one citizen died in his apartment when the floodwaters rose rapidly in downtown Aguadilla on Wednesday evening.

The TF cleared targets in north Aguadilla and then was diverted to a hotel that overlooked the beach in Aguadilla. It was reported to the IST that 16 members of a family were visiting Aguadilla when Hurricane Maria made landfall and needed immediate assistance. The family was low on fuel and was out of food and water. The hotel staff had abandoned the hotel to care for their families. The family was waiting to leave Puerto Rico, but the first flight off the island was not until October 2. The family had contacted a relative in New Jersey, who contacted their state senator. The senator called Washington, and the message was forwarded to the IST. Three hours after making contact with their family member, VA-TF2 and MA-TF1 met seven adults and nine children. The TF gave the family members all the MREs and water they had in their vehicles and on their person.

VA-TF2 and FL-TF2 worked in challenging conditions. They visited 2,311 structures, assisted 51 citizens, evacuated 18 citizens, rescued three people, and identified 60 roads that were blocked. The TFs made multiple contacts with mayors, police chiefs, government officials, hospitals, and other medical care facilities to determine community needs. Also, VA-TF 2’s structural engineers assessed and surveyed a dam in the northwest part of Puerto Rico to determined degradation and potential for failure.

September 25: Day 5 After Landfall

VA-TF2 was demobilized effective 0800 hours. The TF departed San Juan at 2000 hours. The TF landed in Norfolk at 12:00 midnight and was released from the point of departure at 0100 hours on September 26.

Lessons Learned

Communication: The TF was dependent on current and accurate information to plan for the next operational periods and to operate safely. Hurricane Jose was days behind Hurricane Irma, and the TF leaders needed accurate information to keep the TF safe. When Internet and text capabilities are out or not functioning following a natural disaster, satellite phones are necessary for accountability and providing situation reports to the CP and the IST. Invest in communication devices that can operate with no cellular service to include no Internet and no texting capabilities.

In addition, communication with members traveling away from the BoO is critical, especially when line-of-site is not able to reach portable to portable. Responders working in disaster areas need to secure communications with the IST and the authority having jurisdiction so that accountability occurs and the potential for duplicating rescue efforts is minimized.

Logistics. Obtain navigation-capable devices or applications that work with no cellular service. An inexpensive and practical application that provided accurate navigation was MAPS.ME. This application and associated maps of Puerto Rico and the USVI were downloaded when the TF had Internet and allowed the search team managers to navigate without cellular connection.

Logistics. When operating on islands, the local fire and rescue departments have little to no means to move or transport sick or injured people. Be prepared to care for sick or injured patients on the island or in the area in which you are working, and prioritize the medevac of patients when air support becomes available.

Operations. Develop and provide members the defined rules of engagement when operating in another jurisdiction. Develop relationships with the local EOC or government officials and provide search and rescue operations that the locals understand.

Logistics. When the National Response Coordination Center (NRCC) is assigning emergency support functions when providing federal assistance to a disaster area, each federal employee must understand that everyone is competing for the same limited resources. For example, ESF 8 is trying to get DMAT to the disaster area while ESF 9 is trying to get US&R into the disaster area. Both support functions are competing for the same limited resources. Also, force protection (ESF 13) is shared/spread between the two important functions: the search and rescue and the public health missions.

(9) VA-TF2 and FL-TF2 work to evacuate citizens in Toa Baja using a high-water vehicle.

Situational awareness. Develop a method for providing working responders with real-time road closures and immediate updates on dam breaches or failures. As VA-TF2 moved across Puerto Rico, streets to primary roads were not passable. The water continued to rise, and there was the potential of the dam failing while the TFs worked downstream of the dam. This situation necessitated constant situational awareness of the parts of the Planning team manager and the TF leaders. Additionally, the route into a targeted search area may not be the route out if flooding occurs. GPS tracks and coordinates need to constantly be recorded and transmitted to ensure the TF leaders and the IST are aware of a TF’s location and movement.

GPS. Proficient use and understanding of GPS units are essential when responders travel by ground, boat, or aircraft. With limited communications, cell towers are not operational and extraction points for responders may be identified only by GPS. Also, when the roads are not identifiable by street signs or landmarks, the GPS can mark waypoints and extraction points for teams and rescued civilians. USNG and latitude/longitude may be the only coordinates that can ensure your team is found, extracted, or rescued if needed.

Water. The water environment is challenging: All responders who operate in disaster conditions must have situational awareness when navigating unknown water and waterways, especially when the waterway is not on any map or chart. The team’s lack of familiarity with the area, lack of fitness that may be affected by a lack of sleep because of the need to effect rescues, and the complexity of the rescue or mission can hinder the team’s capabilities. The environment includes high heat and humidity, and wearing personal protective equipment, like dry suits, waders, and Level B hazmat suits (for waters that may be contaminated with fuel, chemicals from plant discharges and runoff from containment areas, raw sewage, and anything else that can float and come downstream) can tax team members. Also, when the team enters areas that are navigable only by water, its members must be creative when traversing the boats and entering homes.

Michael J. Barakey, EFO, CFO, has been in the fire service since 1993. He is a district chief with the Virginia Beach (VA) Fire Department assigned as the C Shift commander and oversees Special Operations. He is a hazmat specialist, an instructor III, a nationally registered paramedic, and a neonatal/pediatric critical care paramedic for the Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters in Norfolk, Virginia. Barakey is a plans team manager for the VA-TF2 US&R team and has been deployed numerous times. He is an exercise design/controller for Spec Rescue International. Barakey has a master of public administration degree from Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia; is a graduate of the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program (2009); is a peer assessor for the Commission on Fire Accreditation International; and is a chief fire officer. He regularly contributes to Fire Engineering and is an FDIC International classroom instructor.

VA-TF2’s Response to Hurricane Irma and Maria

(1) TF members help locals to clear a road. (Photos courtesy of Virginia Task Force 2.)

(2) Loiza, showing minor flooding on the main road, a broken utility pole, and down power lines.

(3) The Guajataca Dam, viewed from the backside. The spillway is damaged, and major erosion is occurring downstream. The dam, itself, is intact.

Jack Phillips, PE, is a structural specialist for Virginia Task Force 2.