The Rescue of Salvador Peña

THE NORTHRIDGE EARTHQUAKE

One of the defining moments of the Northridge Earthquake was the rescue of Salvador Peña from beneath the collapsed Northridge Fashion Center parking structure. Peña was entombed under tons of concrete within the wreckage of a street sweeper for nine hours. The rescue efforts required the combined efforts of several fire/rescue units from the City of Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD), a technical rescue unit from the Los Angeles County Fire Department, an engine strike team from the Orange County Fire Department, equipment from the Southern California Gas Company, and a local lumber company. As aftershocks continued to rock the area, firefighters risked their lives for hours beneath massive, unstable concrete slabs to free the victim. Pena is now back with his family, a tribute to his own tenacity and the skill, persistence, and bravery of rescuers who promised they would not leave without him.

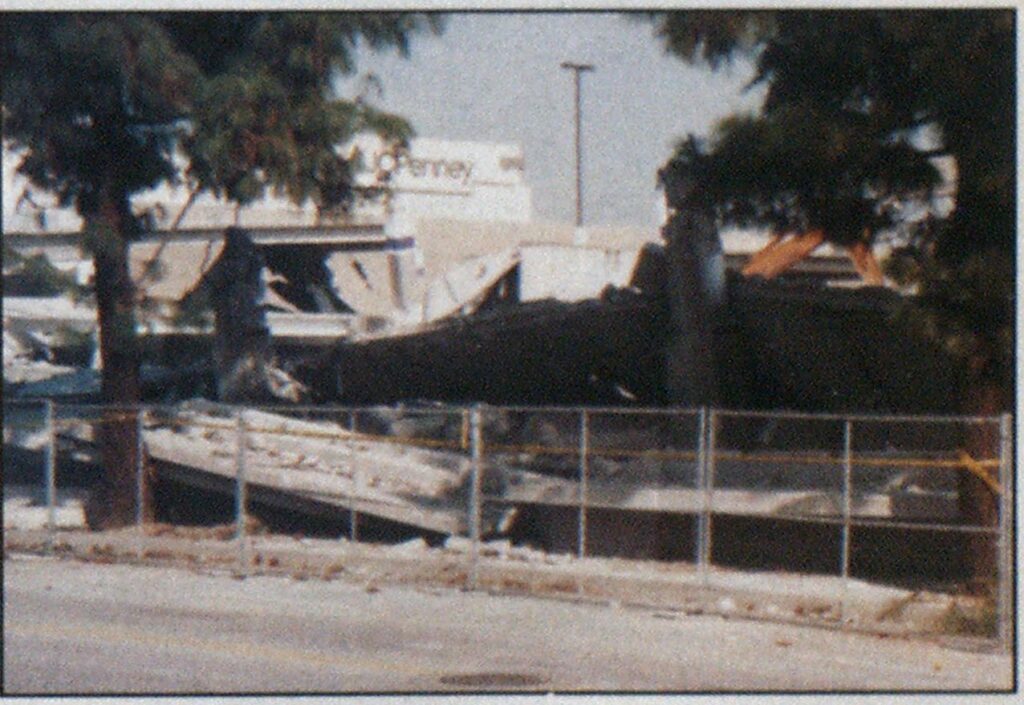

THE COLLAPSE

It began with a typical day at work: In the early morning darkness, 43-year-old Salvador Pena drove a street-sweeping truck through the first level of the three-story parking structure at the Northridge Fashion Center. Nine miles beneath the surface of the San Fernando Valley, a long section of crustal rock heaved and fractured. The earth began to shake violently.

The concrete slabs overhead separated from their support columns, and two levels fell onto the truck, with Pena in it. One three-foot-thick concrete beam slammed down on the truck cab at the steering wheel, crushing Pena’s legs and one hand. Another beam crushed the truck directly behind Pena’s head and back, missing his torso by inches. Pena was trapped in an upright position. twisted at an odd angle, unable to free himself as the quake continued to crush and twist the wreckage.

When the earth finally stopped moving, Salvador Pena had been buried alive.

FIRST RESPONSE

A security guard had seen Pena’s truck enter the structure some time before the quake. After investigating, he called LAFD. At 0600 hours. Light Force 89 (LF 89) was dispatched to a “person trapped” at the Northridge Fashion Center.

LF 89 was met by mall security officers, who pointed out the area where the sweeper was last seen. Captain Tom Burau noticed that lights were still on in parts of the collapsed structure. Firefighters climbed over the debris to an area where a voice was heard from void spaces between the slabs. Realizing Pena could speak only Spanish, Burau asked a bilingual firefighter to interpret. They learned that Pena was reasonably alert, was trapped alone in a truck on the first floor, and seemed to be severely injured (he could not feel his legs or his right arm and was in ex trente pain). Burau instructed the firefighter to maintain voice contact with the victim while a rescue strategy was determined. The smell of gasoline was strong through cracks and voids, and Burau assumed it was from a ruptured tank on the sweeper.

Burau contacted OCD (LAFD’s dispatch center) and requested an engine company equipped with AFFF, a USAR team, and a paramedic ambulance. He asked mall security to disconnect power to the parking structure to eliminate threat of electrocution to rescuers. Then he assigned a firefighter to survey the site for access to the sweeper truck.

(Photo at top by Glenn P. Corbett; photo at bottom by Tony Zar.)

The firefighter found a tiny void that seemed to lead into the area of the sweeper. He crawled into the crack and managed a glimpse of the truck. However, the gasoline vapors were so strong he knew he might be incinerated if ignition occurred. He exited and reported his findings to Burau, who ordered his crew to avoid entering the space until the gasoline could be dealt with and the structure stabilized. A perimeter marked by fire line tape was established around the danger zone.

Engine 1 arrived, and LF 89 personnel applied six-percent AFFF solution into cracks and void spaces in and around the sweeper. All hydrants in the vicinity of the mall were dry due to water main ruptures, so booster tank water was the only option. Since only five gallons of concentrate were used initially, this did not pose an immediate problem. However, Burau recognized the need to establish a continuous water supply to periodically maintain the foam blanket and to extinguish a flash fire should that occur.

Sharp aftershocks continued to strike. Each one set the entire parking structure in motion. Slabs shifted, debris rained down, and still-hanging sections of the structure threatened to collapse on rescuers. The site, unsafe to begin with, was becoming increasingly more hazardous. Even the safety of working from the top of the debris pile was questionable, as the pile itself could shift at any moment. If not for the presence of a confirmed live victim, Burau would have secured the structure and left it for the search dogs and demolition crews.

LF 89 and Engine 1 discussed their options. They decided to begin opening some access holes adjacent to and above the sweeper using sledgehammers, a slow process under any circumstances. To expedite this operation, Burau assigned two members to procure a compressor and jackhammers from a rental yard.

At about this time, the lights in the collapsed parking structure went off, signifying disconnection of power to the building. Burau confirmed with mall security that it was they who had cut the power (and that it was not just a temporary blackout).

USAR TEAM “TRIAGES” THE COLLAPSE

Members of the LAFD Disaster Preparedness Unit assembled two six-member squads of USAR-trained firefighters at Valley Command. Deployment of the full LAFD USAR task force was not immediately possible due to the impact of the quake and the many other incidents that had to be addressed.

One of the squads, headed by captains Ron Leydecher and Craig Morrison, was dispatched to the parking structure, arriving at approximately 0715 hours with the LAFD trench rescue unit and a trailered cache of equipment. At the same time, radio reports from other units indicated that a major collapse with at least 20 trapped victims had occurred at the Northridge Meadows Apartments. USAR resources were being requested to assist with rescue operations at the Meadows.

Leydecher and Morrison sized up the parking structure collapse and knew that rescuing Pena would take many hours and that his survival was questionable even in the best-case scenario. They determined that more lives could be saved if they immediately redeployed their group to the Northridge Meadows Apartments. They advised LF 89 and Engine I to continue with their rescue strategy, advised command that mutual-aid USAR resources were required immediately at the Northridge Fashion Center, and proceeded to the Meadows, where they would assist with several lifesaving operations.

Light Force 89 and Engine 1 regrouped and began laying the groundwork for an extended rescue operation. Meanwhile, at 0718 hours, LAFD dispatchers requested a USAR unit from the L.A. County Fire Department (LACFD) to respond to the Northridge Fashion Center collapse.

ADDITIONAL USAR RESOURCES ARRIVE

USAR1, LACFD’s technical rescue unit, equipped with a variety of technical and heavy rescue tools, arrived at 0750 hours. Captain Wayne Ibers reported to Burau, who described the rescue problem, the actions taken, and the preliminary rescue plan. Burau designated Ibers rescue group leader and assigned the crew of LF 89 to work with USAR1. Ibers and his crew surveyed the site anil agreed that initial actions to open access holes down into the collapse zone should continue.

A short while later, LAFD Heavy Rescue 56 (HR 56)-a heavy duty wrecker/rescue unit equipped with a 20-ton boom, an air compressor, jackhammers, air bags, a cable winch, heavy timber shoring, several types of jacks, and other heavy rescue equipment-arrived. Shortly thereafter, LAFD firefighters arrived with a work truck they had commandeered from the Southern California Gas Company. It was equipped with a generator, air compressor, jackhammers, and other tools that would prove helpful during the rescue. Workers from the gas company welcomed LAFD members to make full use of the truck for as long as it was needed. There were now at least eight jackhammers on the scene.

RESCUE PLAN ESTABLISHED

Burau assigned HR 56 to the rescue group with Ibers. HR 56 Apparatus Operator Tony Zar and Ibers climbed through a void space under the third and second floors to get a better handle on the rescue problem. From this survey, they developed a threephase rescue plan:

Phase One: Clear as much weight as possible from the surface of the collapse and cut several sections from the thirdlevel deck (to lessen the load that would later have to be lifted and to clear access routes). Jackhammer through both decks to create access/exit holes. The holes had to be large enough to accommodate all rescue equipment, as well as accommodate personnel who would attempt to provide essential medical treatment as quickly as possible.

Phase Two: Working from below, crib and shore the upper two levels in preparation for a major lifting operation. Using four carefully positioned air bags, coordinate efforts to slowly lift the second and third decks high enough to allow for vehicle extrication operations.

Phase Three: Cut the vehicle apart and extricate the victim. Provide C-spine and rapidly evacuate the victim to the surface, where a paramedic team and an LAFD paramedic helicopter would be waiting for immediate transport to UCLA Medical Center.

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS

Safety of all rescuers was of primary importance. Prior to the beginning of operations, Burau, Ibers, and Zar conducted a safety/operational briefing with all personnel. In addition to describing the rescue plan, they discussed the following safety issues:

(Photo by Rkh Meline.)

- Danger areas. Portions of the structure adjacent to the pancaked collapse site were still standing. Even without aftershocks, they were in danger of catastrophic collapse; the aftershocks simply increased the likelihood. This scenario presented many overhead hazards for rescuers working the rubble pile. Due to this danger, certain areas were taped off limits at all times.

- Escape plans. At all times, escape plans would be in place for personnel on top of the collapse and in the hole. Escape plans were to be implemented during major aftershocks, fires, and any other adverse events. The escape plans were utilized several times during the day.

- “Safe” zones. Whenever personnel were working in areas where rapid escape was not possible, nearby protected areas were to be planned as “safe zones” where personnel would “ride out” aftershocks and other adverse events. These, too, were used | more than once.

- Communications. Line-of-sight voice conversation was to serve as the primary communications method. Hand-held radios were distributed and channels synchronized to ensure constant radio communications

- between remote sites in and around the collapse.

- Signals. Whistle signals were to be used as an “all stop” signal whenever an adverse event threatened operations. Whistle signals were also to be used in case of voice or radio communications failure or if any rescuer needed emergency assistance.

- Equipment. Appropriate safety equipment was to be used at all times.

- Confined space. Some tasks during the Pena rescue definitely fell within the realm of confined space operations. Standard confined space precautions were required (i.e. monitoring of explosive atmospheric levels, forced ventilation “in the hole,” explosionproof lighting and radios, backup rescue teams, etc).

- Cutting. All cutting and jackhammering procedures would be coordinated through the rescue group leader before beginning. Personnel above and below had to be aware and out of the way of potential hazards of cutting operations.

- Lifting. All lifting operations would be coordinated through the rescue group leader. Lifting and shoring teams absolutely had to coordinate all efforts throughout the operations to avoid catastrophic collapse and life loss.

PHASE ONE

The briefing complete, operations on Phase l began with the clearing of chunks ot concrete and other debris from the deck of the collapsed structure. This was laborintensive and back-breaking work for all members, now working under a hot sun. As the clearing proceeded, firefighters began cutting the top layer of the deck with jackhammers. During this operation, which lasted more than two hours, Ibers assigned USARl engineers Ysidro Miranda and Richard Meline-both paramedics-to take turns in the hole with the victim, rotating every 20 minutes or so. Their assignment was to provide medical treatment, monitor Pena’s vitals, and keep his spirits up during the operation.

Rapid medical treatment is essential in cases of collapse victims to prevent crush syndrome. Victims whose limbs or other body parts are being compressed should begin receiving IV fluid therapy, cardiac monitoring, and other treatment early in the course of long-term extrication operations; if not, the patient may succumb to effects of hypovolemia, the sudden release of the byproducts of tissue compression, kidney failure, liver failure, fatal cardiac arrhythmias, or other life-threatening problems (some of which may be preventable). (See “Crush Syndrome.” Fire Engineering, May 1994, p64.)

Rescuers faced exactly the type of scenario that could result in crush syndrome. Meline crawled into the hole with IV solutions, oxygen, and other medical equipment. Lying on his back, he attempted to establish an IV in Pena’s arm. The attempt failed and the vein “blew.” After several more attempts, it became apparent that intravenous therapy would not be possible until more of the victim’s body could be exposed. The only option was to monitor him, comfort him, apply oxygen, and get him out of there as soon as possible. Rescuers were concerned that Pena might not survive long enough to be brought out alive.

As Meline and Miranda took turns with Pena, they identified solid lifting points that would later be used to lift the second floor slab off the truck. They also developed plans for extrication and evacuation of the victim.

During Phase l, several large aftershocks struck, sending Miranda and Meline scurrying for a “safe zone” they had identified. In this case, the safe zone was simply a crawl space that appeared to be more stable than the surrounding collapse area. In reality, there was nowhere for Miranda or Meline to escape; the threat of catastrophic collapse of the site was everpresent.

Above, firefighters continued to jackhammer through the thick concrete in a pattern designated by Ibers and Zar. Meanwhile, planning two or three steps ahead, Burau was working to get resources in place to continue progress of the operations. Available LAFD firefighters who had just been released from several hours of intense rescue work at the Northridge Meadows Apartments collapse were requested to find a load of heavy timbers for Phase Two shoring operations. A local lumber center gladly obliged the firefighters. Within an hour, a full load of lumber, heavy timbers, hammers, nails, saws, and other essential items was delivered.

Burau also asked Valley Command to send an engine strike team to assist with debris removal and to cut shoring timbers. A strike team from the Orange County Fire Department (OCFD) was dispatched. A cutting station was established in a section of the mall parking structure one-eighth of a mile from the rescue site so as to reduce the noise factor during sensitive lifting and cutting operations. A utility vehicle would be used to shuttle lumber and cribbing from the cutting site to the point of entry.

LAFD Battalion Chief H. Louis Chatin arrived shortly after 1000 hours and assumed overall command of the incident. Burau was the tactical commander. The OCFD strike team, with five engines and one battalion chief, arrived. Chatin directed them to conduct a complete search of the rest of the parking structure to make certain Pena was the only victim.

Burau, Zar, and Ibers agreed to step away from their respective tasks every 30 minutes to brief each other, compare notes, and adjust the rescue plan and the incident action plan as necessary. At one such meeting, they agreed to request a paramedic rescue helicopter from LAFD to land and stand by in the parking lot when it appeared that extrication of Pena was nearing. Paramedics from LAFD Rescue Ambulance 104 contacted their base station to report the situation and the condition of Pena. After discussion with Ibers, Burau, and Chatin, they made specific contingencies for treatment of Pena’s crush injuries, including arrangements for immediate flight to the UCLA Medical Center/Trauma Center for treatment.

PHASE TWO

Ibers was comfortable that sufficient concrete had been cleared from the third floor deck, and after he, Zar. and Burau had determined the access/egress holes to be of sufficient size, Burau halted jackhammer operations and conducted another briefing with all personnel. The next steps were discussed, along with a review of critical safety items, including escape plans. All personnel were encouraged to stay well hydrated in the 80-degree sun. The lifting operation was reviewed so all personnel would anticipate the steps and safety precautions.

Phase Two would be more hazardous because eight firefighters would be working in the hole while the second floor was lifted. The potential for ignition of gasoline vapors still was a major concern. Firefighters were ordered to place ventilating fans and air socks to direct fresh air into the hole. Ventilation would continue throughout the operation, as would AFFF foam application. All spark-producing equipment was prohibited under the concrete decks.

By this time, the news media had gathered at the scene. Chatin requested an LAFD public information officer, which was denied due to the magnitude of the disaster citywide. Chatin, monitoring the progress of the operation, periodically updated the media.

Just after l 100 hours, another layer of foam was applied to accessible areas of the gasoline spill. Zar, Miranda, Meline, and Firefighter III Vincent Jenkins crawled through an access hole on the west side of the sweeper truck. They were designated as the West Rescue Squad.

Miranda checked on the status of the victim, who was alternately in severe pain and praying for help and then seemingly in a “trance,” oblivious to the activity around him. As they began Phase Two, Miranda assured Pena they would have him out as soon as possible. At this point, Pena’s physical condition and the unpredictability of the situation left the ultimate outcome of the rescue in doubt. It was obvious that this operation would still take hours.

Precut shoring timbers were passed into the hole on the west side; two air bags, an SCBA bottle, and other equipment followed. One air bag was rated to lift 74 tons 20 inches high; the other was capable of lifting 44 tons 16 inches. A hydraulic spreading/cutting rescue system, a model reduced in size specifically for confined space operations, also was sent into the hole. The power unit was kept on the surface of the collapse due to its ignition hazard; extension hydraulic cables were used to reach the sweeper truck.

Zar and Miranda prepared to shore and crib the north beam, which rested on Pena’s legs and the front of the sweeper. They slid the air bags into place and prepared them for a lifting operation, which would be coordinated with a team on the east side of the truck.

As these tasks were being completed, the HR 56 A shift arrived. Apparatus Operator Dane Jackson was instructed to assist void operations by the West Rescue Squad. Firefighter Mike Porper was assigned to coordinate the supply of shoring, rescue tools, and other tasks on the surface.

Personnel from the OCFD engine strike team were ready to cut timber and shuttle it to the hole. They and firefighters from LAFD Station 70 were essentially the only “backup” immediately available in case of trouble. They reviewed with Burau and Ibers plans to provide fire protection and other safety issues. Hoselines were available with very limited water (all hydrants in the area were still dry).

Meline and Jenkins prepared to crib and shore the south beam, which rested directly behind Pena’s back. The 74-ton air bag, controlled by Zar and Miranda, would lift the north beam, while the 44-ton bag would simultaneously lift the south beam. Mcline and Jenkins would be responsible for constantly cribbing the south beam during the lift.

All four firefighters on the west side stopped to review their escape plan. If there was fire, they would immediately exit through the opening they had entered or retreat to the areas least affected by the fire and smoke. In the event of major aftershocks. there was no quick escape. Travel under the beams, which were only 12 inches off the first-level deck, was ruled out. They decided the safest strategy would be to remain in place between the beams and “ride it out.” While they were going about their work, small aftershocks continued to remind everyone that the danger of major tremors was still very real and the entire structure was still very unstable.

Meanwhile, Ibers led a team into a hole on the east side of the sweeper with shoring, cribbing, two air bags (one with 74-ton capacity, the other rated for 44 tons), a hydraulic rescue system (with the power unit remaining on the surface), and other equipment. They were designated as the East Rescue Squad.

Both sides of the north and south beams were shored. The East Squad then used a hydraulic cutter/spreader to remove the passenger-side door of the sweeper truck. This was necessary for two reasons: First, it gave firefighters better access to the victim, who was drifting in and out of consciousness. Second, and most important, the work space was so small that, if they had placed the air bags and begun lifting first, removal of the door would have been impossible from the east side.

The West Squad was able to break the driver-side door lock with a hydraulic power spreader but was unable to perform any further extrication until the second floor deck was raised.

LIFTING THE SECOND FLOOR

Thus far, Phase Two preparations to lift the second deck had taken a full hour. Before continuing, Ibers had all personnel exit to the surface for a quick break and hydration in preparation for an extended lift/extrication operation. Ibers and Zar reviewed progress with Burau and Chatin.

All personnel were again assembled for a quick briefing. All extra noise had to be deadened during the next operations because voice commands were to be used between the East and West squads to lift the slab, and split-second coordination would be essential to keep the slab level and stable. Large aftershocks during the lifting operation could be disastrous if shoring and cribbing were not exact. For every inch lifted with the air bags, there had to be an inch of cribbing in place to prevent catastrophic collapse in the event of air bag failure or other adverse events.

At 1210 hours, the East and West squads reentered the hole to start the lift. On the surface, everyone took their assigned support positions, and the paramedics updated their base station, alerting UCLA Medical Center to be ready for the patient within approximately one hour.

Tony Zar from HR 56 describes the lifting operations, “The East Squad started the lift with the south beam using a 44-ton air bag to release tension on the third-story beam. As each move was made, cribbing was placed to secure it from falling. Our attention was focused on the north beam, which was the critical beam trapping the victim. As the East Squad put pressure to its air bag, the West Squad would put pressure to its bag, and together we raised the slab approximately one to two inches at a time, then stopped to crib the move.

(Photo by RichMeline)

“During the lifting operation, I controlled the pressure and watched the vehicle and victim, while Meline cribbed the north beam and shored the slab to the west of us, which was a potential unstable point if unshorecl. Jenkins cribbed the south beam….

The only time we would stop was during periods of aftershocks…during these times we would make sure we were in the safest position possible.”

AFTERSHOCK THREATENS THE OPERATION

The East Squad was performing similar tasks in coordination with the West Squad. The operation was interrupted when a 5.3 aftershock struck. Anyone who has experienced a quake of that magnitude can imagine the vulnerability of rescuers sandwiched between tons of concrete with little more than two feet of space. The situation was excacerbated by the fact that they had just finished lifting the entire second-floor deck 10 inches and it was sitting on five columns of freshly placed wood shoring.

The aftershock lasted 1 7 seconds. The parking structure bounced wildly. All four members of the East Squad were able to escape through void spaces before the aftershock was over. The West Squad dropped to the floor and rode it out. Even after the earth stopped shaking, the parking structure kept moving.

This event, according to Ibers, caused all personnel to renew efforts to complete the rescue and get out of the hole as soon as possible. Several other aftershocks prompted a similar reaction from rescuers during the remainder of the operation.

The lifting operation continued until there was enough room to work on the vehicle extrication. During this process, Ibers was concerned that the release of pressure as the north beam was raised from Pena’s leg might result in massive hemorrhage, the release of built-up toxins into Pena’s system, or other uncontrollable problems. He notified the paramedic crew to stand by and notified Burau that they were close. At this time Burau requested an LAFD paramedic helicopter to land in the parking lot and prepare for a life flight to UCLA Medical Center. As the lifting operation proceeded, Pena’s vitals and mental status were monitored closely. He appeared to be tolerating the change in pressure as well as could be expected.

Lifting concluded when the entire second deck had been raised approximately 12 inches. The pressure in the air bags never exceeded 40 psi. Final shoring and cribbing were placed, and the area was secured in preparation for Phase Three.

PHASE THREE

With the second deck of sufficient height to begin dissecting the sweeper’s cab, simultaneous extrication operations began on both sides.

Zar, who supervised ihe West Squad, explained, “On our first attempt, we tried to use a small ram from the “A” post to the “B” post to move the roof away from the victim. This created pressure to his thighs and had to be stopped….At this time, Meline felt he could slip through an opening about 16 inches high and 24 inches wide into the cab to remove the driver’s door hinge.”

Zar passed the power spreader inside the cab to Meline, who was able to pop the door. Then the East Squad worked to spread the roof away from the seat to free Pena’s right hand. The West Squad cut the “A” and “B” posts, then the East Squad removed the roof through its side. Now, the only thing holding the victim was the dashboard.

This marked another potentially dangerous point in the rescue: Once again, weight was to be removed from Pena’s legs. There was renewed concern about the potential for massive bleeding and septic shock. All personnel discussed the next series of moves to expedite operations once the dash was lifted. Zar described these rapid actions: “1 was able to muscle the “A” post away from his leg. while Meline used the hydraulic power spreader in a scissor method to spread the dash apart. Then 1 requested a flat to be brought in to remove the patient.”

With the victim freed, both squads worked to remove him from the cab under extremely tight conditions. Every movement brought agony to Pena, whose legs were crushed. After packaging him for removal, they began pulling and dragging Pena through a route under tw’o beams and through the access holes to daylight. It had been less than five minutes since the dash was lifted.

Once out of the hole, firefighters and paramedics carried Pena through a circuitous route across the top of the collapse. At 1315 hours, they handed Pena down the rubble pile and started toward the helicopter. It was almost nine hours since the earthquake had struck.

(Photo by Rich Meline.)

(Photo by Tony Zar.)

REHAB

After checking to see that all members were safe, uninjured, and well hydrated. Burau and Ibers brought the entire group together again. The next operations, he explained, were perhaps the most dangerous. There was still an unknown number of active rescue operations in progress in the city, and the units would have to be made available for the next assignments. They needed to enter the hole to remove essential equipment, including the air bags that still helped support the deck weight. Ibers reiterated all the safety precautions, essentially the same that had been used all day. He cautioned rescuers against letting their guards down, which is common after a victim is removed.

Slowly and carefully, the crews worked in coordination to pull cribbing and lower the slab. Once the air bags were clear, cribbing and shoring were tightened to secure the load. Then the bags were pulled, one by one. All essential equipment was dragged out of the hole while rehabilitation of other equipment was conducted on the surface.

There was really no time for conducting a critique; by now, all personnel were aware of the large life loss incident occurring just three miles away at the Northridge Meadows Apartments. The scene was secured and turned over to mall security. All units were made available for response.

RECOVERY

Salvador Pena, whose life nearly ended under tons of concrete, underwent hours of emergency surgery at UCLA Medical Center. Doctors treated him aggressively for crush syndrome, internal injuries, crushed legs, and other life-threatening problems. Considering his predicament, Pena’s survival seems almost miraculous. His legs were not amputated, and he underwent intensive rehabilitation treatment for weeks after the quake. Recently, Salvador Pena began walking with assistance.

LESSONS LEARNED AND REINFORCED

- The rescue of Salvador Pena clearly demonstrates the benefits of heeding lessons learned from past disasters. The conditions in the collapsed parking structure came as no surprise to the USAR-trained personnel from LAFD and LACFD; the need for advanced capabilities to rescue victims from collapsed reinforced-concrete structures had been demonstrated in a wide variety of disasters, each of which has had striking similarities: Victims were trapped for extended periods of time by reinforced concrete, structural components, and other debris; access for search and rescue workers was complicated by the difficulty of cutting and tunneling through multiple layers of reinforced concrete; treatment of injuries and crush syndrome was complicated by the same conditions; and rescuers worked for extended periods in areas vulnerable to secondary collapse.

- Accurate initial assessment of damaged structures by all firefighters and first responders sets the stage for effective rescue operations. Factors such as time of day, type of occupancy, type of construction, extent of collapse, potential for live victims trapped in void spaces, and potential for successful rescues are critical to this determination. In the Pena rescue, Burau accurately identified the rescue problem and requested the resources needed to complete the rescue. His actions and decisions are a good example of the importance of having well-trained, experienced engine and truck companies.

- Local officials and fire departments would do well to consider organization and training by which “ad hoc” local USAR teams can be assembled at a moment’s notice during the early stages of a disaster event-the stages during which resources are the scarcest and response actions the most important.

- Collapse site “triage” is an important USAR concept when disaster strikes. It allows the officers to dedicate resources so that they achieve the greatest good for the greatest number. Had LAFD USAR 1 committed to the Pena rescue and not moved on to the Northridge Meadows Apartments collapse-which had a higher potential for live rescues-it is possible that some rescues at the Meadows would have been too late. While it may be extremely difficult to leave a rescue site, an objective risk-vs.-gain evaluation is essential.

- Interagency cooperation and planning are essential to effective disaster response. LAFD HR 56 and LACFD USAR1 have trained and worked together on mutual-aid incidents for years. Members of both units know each other well and cooperate in researching and developing new heavy rescue methods and tools. This working relationship proved crucial to the rescue of Salvador Pena.

- Reinforced-concrete parking structures are prone to collapse. Know the buildings in your area. Know which are most likely to fail in a natural disaster. Earthquake preplanning is necessary.

- A rescue operations plan-the rescue strategy-is essential in a complex extrication such as the Pena rescue. All members on the scene must clearly understand the plan-there should be no surprises to any member involved in the operation. Frequent briefings are important. Rescue plans should be constantly monitored, reviewed, and updated. Formulate contingency plans.

- Tactical planning is also essential. At the Pena rescue, for example, conditions were such that operating the air bags prior to removing the sweeper door could have been disastrous. Think- and have a plan-before you act in a collapse rescue situation. Always remember that every action has a reaction.

- The importance of understanding and treating crush syndrome cannot be overstated; training and treatment protocol should be instituted for paramedics, EMTs, firefighters, physicians, nurses, and other medical personnel.

- Address the “confined space” hazards of a collapse rubble pile, such as dangerous atmospheres. Do not commit members to a potentially dangerous atmosphere without breathing apparatus until the threat has been eliminated or reduced to an acceptable level. Monitor explosive levels, ventilate the area if possible, use intrinsically safe equipment if conditions dictate, etc.

- Establish and maintain safe zones and danger zones. Secondary collapse hazards, such as structural debris suspended overhead. adjacent to, or removed from the immediate rescue area should be marked (taped or roped off) and off limits at all times during the operation.

- Designate a backup rescue team(s)/relief team(s) to be readyduring the entire operation.

- Consider how ancillary or other operations around the site will affect the stability of the collapsed area. Stage timber-cutting operations at a location such that additional vibrations will not jeopardize the stability of the rescue area.

- Every effort should be made to wear proper and full safety equipment at all times. However, this can be difficult at times, particularly during certain collapse rescue operations. Firefighting helmets generally are not designed for use in tight spaces for long periods of time. In some cases, rescuers were forced to remove their helmets to operate. This should be considered ahead of time for personnel likely to be involved with such operations.

- Plan egress routes and safe zones for members working in the rescue area.

- Establish emergency signals for the operation, such as “all stop” and “need assistance” messages. Whistle signals may be effective in this regard.

- When lifting and shoring a heavy load, the slightest wrong movement can spell disaster. Communication and coordination between operating personnel are the keys to success and safety.

- When lifting and shoring a heavy load, short, incremental lifts and continual cribbing are much safer and controlled methods of operation.

- Though reinforcing cables in the concrete trapping Pena were already snapped and loose from the force of the earthquake and the physics of the collapse, rescue personnel must understand the hazards and difficulties associated with this type of cutting operation. (See “Cutting Reinforced Concrete,” Fire Engineering, August 1992, for more information.)

- Establish agreements with local companies and agencies to secure vital equipment resources during disaster events.

- Maintain voice contact with and comfort and reassure the victim at all times during the operation. If members on the scene cannot speak the victim’s language, request a firefighter to the scene who can.

- Fatigue will be a major factor at extended rescue operations. Schedule frequent rehab periods. Call for additional resources.

- This rescue, and the Northridge Earthquake as a whole, should serve also as lessons for officials nationwide with responsibility for managing disaster-related rescue problems. Disaster response

- plans must reflect genuine disaster possibilities. The disaster response community must ask itself, What if the earthquake had occurred at 1600 hours on a busy shopping day? What if hundreds of people were in the parking structure? and other hard questions.

The lessons learned from these past incidents and nationwide USAR efforts to improve the safety and effectiveness of rescue operations in collapsed reinforced-concrete structures-efforts that include working with structural engineers, research scientists, construction companies, demolition contractors, heavy equipment operators, heavy shoring contractors, and technical search specialists-have been directly applied to USAR training and response plans. When Captain Ibers and the crew of USAR1 arrived at the parking structure collapse, they had already identified a generic plan for rescue operations. That plan, combined with the ability of LAFD and LACFD personnel to adapt to the specific conditions encountered, resulted in the successful rescue of Pena.

USAR officers and firefighters must continue to translate lessons learned into action-and share the lessons with others.

Be it earthquakes or other natural disasters, it is certain that disaster preparedness has not been perfected in the United States. It is necessary for federal, state, and local officials to move “full speed ahead” to establish sufficient USAR capabilities necessary to manage major quakes and other disasters that will occur.

- The nature of disaster triage makes it essential that the first company that assesses a collapse incident with a live victim, before moving to another incident with a higher priority, mark the structure so that other companies driving past later can clearly recognize the situation-this is critical to lifesaving operations in disaster situations. Other rescue teams driving past should be able to look at the marking symbol and understand the building’s condition, the number of victims trapped, access/egress points, specific hazards, the identity of those who marked it, the time of the search.

(Photo by Gail Fisher/I os Angeles Tones.)

- and other critical information.

- The techniques and equipment used to rescue Salvador Pena are included in standard California Rescue Systems I training. Rescue Systems 1 is one component of required training for California Office of Emergency Services (OES)/FEMA USAR task forces. Thousands of firefighters in California and other states have been trained in these techniques. The ability of personnel from LAFD, LACFD, and OCFD to coordinate their efforts with minimal difficulties has its roots in California’s emphasis on standardized rescue training.