Training Notebook ❘ By SCOTT HUFF

The dive team is dispatched to a local apartment complex’s retention pond, known for its many entanglement hazards, on a report of a possible drowning.

- Water-Related Missing Persons Operations

- Training Options for Your Dive Team

- The Public Safety Dive Team: Is It Time to Push the Pause Button?

- Dive Rescue Series: Locating Your Objective

As the crews are en route, the dispatcher reports a 10-year-old autistic child has gone missing and was last seen playing at the water’s edge. Approaching the scene, the team encounters a frantic woman, who says that a 10-year-old autistic boy was last seen struggling at the water’s edge. The officer asks her where the boy was; she points and says, “I saw him go under over there.”

With the excitement of making a rescue, the divers quickly dress, and a search begins from the bank where they met the witness. The search lasts about 40 minutes with several diver rotations, but no one is found. The residents from across the pond, watching from their balcony, state to a nearby crew that they saw the boy in a different part of the lake, not far from where the team was operating. The information is relayed from the balcony and, within five minutes of searching in the new location, the boy is rescued and rushed to the hospital.

Although the dive team was ready and eager to dive, the vague information led the crews to an initial entry point in the wrong place, delaying the rescue. The witness interview should ensure that the witness is taken back to the primary location he was standing when he saw the event. In this case, the woman was not where she had been standing when she saw the boy go under because she had run toward the rescuers as they approached, so her estimate of the distance was way off. The witness interviewer should have asked, “Where were you standing when you witnessed the boy go under?” It is critical that the team starts the dive operation from the exact point of view of a reliable witness.

Preplanning High-Probability Dive Rescue Areas

Discretionary time is any downtime when we are not training, at meetings, or on emergency calls. Use this time to preplan, explore with sonar, map, and make local inquiries about the high-probability dive rescue areas to which our divers may respond to enable the team to determine some of the unknowns about the area. These include its depth, its bottom composition, any obstructions and hazards, and its clarity, knowledge of which gives divers a great advantage in a rescue. Just as most fire crews preplan during an emergency medical services (EMS) call, observing the inside of a structure, the building construction, the interior layout, the location of stairs, and so forth to preplan for a fire in that same structure, so should dive teams. This is an opportunity for you to get an idea about the population, the age groups, and what issues you may face—such as recreational activity on the water or if “No Swimming” is posted and monitored.

Most operational dive sites are cramped with limited access to the water’s edge and become a challenge for additional dive crews and EMS personnel to access. Preplanning enables companies to practice staging apparatus and figure out the best possible way to get transporting units in and out of the area quickly. Consider the time of day; in cramped areas during the daytime, more cars may be in the way vs. at night.

Interviewing the Witness

Teams should make it a high priority to immediately seek out and establish a credible witness who can give accurate information before you ever commit divers to the water. You do not want to commit them to the wrong areas and waste valuable time relocating them, as in the scenario above. A frantic woman provided information, and the focus shifted quickly to rescue and putting divers in the water, prior to obtaining and confirming that the information was accurate.

Teams get into trouble by having tunnel vision and committing divers to the water without proper witness interviewing, just to get divers into the water. We must slow down, focus on the big picture in this phase, and designate a team member as a witness interviewer. This member has no other function than to seek out a credible and accurate witness. Once you have obtained accurate information, you can then place the divers into the best access point for the best possible outcome.

When you have no credible witnesses, teams will have to rely on other physical clues and observations that may present themselves on the scene, such as handwritten notes, piles of clothing, disturbed areas in the water or vegetation, or tracks leading into the water. When making a dive/no-dive decision without any information or witness on the scene, teams face investigating what is normal for that specific area. Knowing the area comes from preplanning and having a predetermined dive plan. Committing divers to the unknown call, with unknown circumstances, in unknown areas puts divers in the water searching at extreme risk. An ongoing evaluation of risk vs. benefit should be the deciding factor during these types of unknown calls.

(1) An interviewer with several witnesses is narrowing down the last-seen point. [Photos courtesy of the Indianapolis (IN) Fire Department.]

(2) With the witness, the interviewer gives a hand signal to the diver, directing him to the last-known location.

(3) A diver in full PPE.

Witnesses

Most witnesses want to help and are willing to give information, but not all witnesses will be reliable. Finding out who is reliable should be ongoing.

- Some may not be willing to step up and offer information or are afraid of being attacked and getting into trouble if they provide information. You may have to seek out these witnesses and confirm they are credible and urge them to provide any information because it is needed to save a life.

- Some may need an interpreter to communicate. Most dispatch centers have the resources to obtain an interpreter.

- Some may not have witnessed the incident but want to help. Move these witnesses to an area where they are out of the way and not distracting the interviewer while he is identifying credible witnesses.

- Young children could be intimidated by male interviewers, so a female interviewer or a soft-spoken male may be the best option.

- Intoxicated and disruptive witnesses may require law enforcement to interview.

- The witness interviewer’s role is to seek out the most credible witness who gives the most accurate information based on witnessed events, not on misleading assumptions. Most important, ensure the witness is taken to the specific location he was at when he witnessed the victim go under.

Witness Interviewer

Assign the interviewer role to a designated member of the team who is personable and has approachable qualities. Not all firefighters possess this trait at times.

- Establish a witness quickly. Be firm and clear with no leading questions.

- Ensure the witness is credible. Ask, “Did you see the victim go under?”

- Place the witness back in the exact location he was at when he saw the victim go under, which may not be the same location you encountered him on arrival. It is extremely important to get him back quickly to the correct spot to get an accurate last-seen point. Say, “Take me to where you were standing when you witnessed the incident.”

- Once back in the exact location, have the witness verbally direct you as you guide the diver on the surface using hands signals. The diver will surface swim to the reference point the witness is guiding you to before the search pattern is started. Be sure to use reference points and visual distance, not a measured distance. Five feet to the witness is usually not exactly five feet. Once it has been confirmed that the diver has reached the spot, have the diver descend and start the predetermined pattern.

- Gather the name, address, phone number, and a detailed statement from the witness, in case this individual must be recalled to the scene. Hold onto the witness’s driver’s license or other identification to ensure he will remain at the scene until the correct area is identified.

Scenario-Based Training

Preplanning and holding scenario-based training in high-probability areas will strengthen your team’s ability to conduct a rapid and accurate witness interview and obtain the best last-seen point placement for your divers. This gives your team the best chance to save a life in a rescue. All dive team members can benefit from real-time training. Familiarity with high-probability areas increases responders’ confidence and enables them to maintain calm in a hectic situation.

(4) The backup safety diver is in position at the water’s edge, ready to deploy.

Figure 1. Andrew’s Drill

1. Divide the team into witnesses and interviewers.

2. Witnesses will view float location and choose landmarks on the opposite shore. Float is then submerged.

3. Interviewers interview witnesses. Based on witness information, interviewers position reference

swimmer on surface.

4. The submerged float is released from anchor and its location is compared to that of reference swimmer.

Four-Phase Training Process

Phase 1. In a classroom session, members learn the expectations and duties of each position, the safety procedures, the medical procedures and requirements, and how to establish and practice interview questions and are made to understand and follow pre-dive instructions and standard operation procedures (SOPs). Roundtable discussions and scenario-based drills will enhance the interview process.

Phase 2. Training is conducted in a controlled environment such as a pool so members can learn and understand team positioning, equipment needs, basic diver skills, search pattern selection, and real-time step-by-step witness interviewing.

Phase 3. Prior to team dive training, using sonar and mapping, members preplan high-probability search areas to identify the bottom composition and discover any obstructions or entanglements in the area. Once you have conducted a safety briefing with all team members and have a plan in place, do final safety checks on all divers and put the training to work in a timed scenario. Train in both rescue and recovery modes. The goal in rescue mode is within 60 to 90 minutes; after 90 minutes, it becomes recovery mode.

Phase 4. In a postincident briefing, review the training and be honest and humble about any issues that arose during the scenario and build off any deficiencies. Share them with the other shifts or teams who could respond to that area. Holding multiagency training is critical when teams respond in a mutual-aid area.

Safety

Two to three public safety divers (PSDs) die in the line of duty every year. The lack of or poor basic scuba skills accompanied by the lack of a true PSD certification and team training time are constant contributing factors in these fatalities. Most PSD fatalities occur in recovery or training mode in unfamiliar areas and with no safety plan in place. Educating divers with an accredited PSD course, having them master basic scuba skills, conducting safe and controlled scenario-based trainings, and preplanning your areas in discretionary time can eliminate these deaths. When performing any operational or training dive, ensure you are conducting an emergency action plan for each area with pre- and post-safety briefings; this can help minimize the tragic number of PSD fatalities each year.

Andrew’s Drill and Training Prop

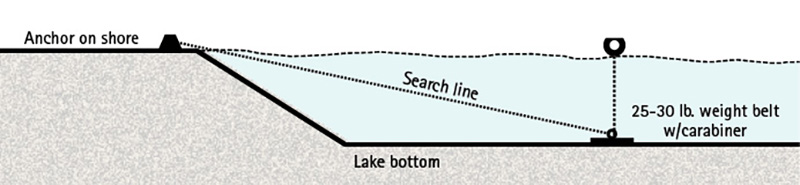

This drill is based on a tragic event that has provided an excellent teaching opportunity for all dive teams in witness interviewing. When done correctly, it will help your team place a diver in the most probable last-seen location. It is easy to set up and uses minimal equipment: one 100-foot (minimum) rope bag connected to a small flotation ball or buoy and a single pulley attached to a small, manageable weight (Figure 1).

Prior to this drill, all personnel must be briefed on safety procedures and entanglement risks with rope in the water. All participating divers must be trained in entanglement risk mitigation with cutting tools. At no time should the weight for the drill exceed the capabilities of a single diver holding it on the surface wearing full personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Without team members seeing, run the rope with the flotation ball or buoy through the single pulley that is attached to the small manageable weight. Have a diver in full PPE surface swim the buoy and weight out to a predetermined location in the water and drop the weight with the pulley. The ball or buoy should remain floating on the surface and the rope bag should still be at the shore.

- Without team members watching, keep the buoy floating on the surface and allow the witness or witnesses to identify its location, then pull the rope in, dropping the buoy under the surface.

- Start your scenario with the team, at the point at which the witness interviewer obtains a credible witness. The witness will verbally explain to the witness interviewer where to swim the diver on the surface to the area where the victim was last seen. Once the diver is in the area according to the witness’s information, release the rope and see where the buoy comes to the surface compared to where the diver was placed.

This drill will help your team prepare to interview and practice last-seen point identification. To make it more realistic, use unfamiliar live witnesses in the area. Most will enjoy helping and learning how the team operates, and it will give your team positive public relations.

SCOTT HUFF is a captain with the Indianapolis (IN) Fire Department (IFD) with 23 years of experience. He is an instructor with the IFD Training Academy; a PSSI/SSI instructor for the Indiana Public Safety Rescue Diver School; and a corporate trainer for Dive Rescue International, teaching public safety scuba across the country.