By Clinton Crafton

Technical rescue isn’t the priority for most fire departments. And for good reason—it’s a low-priority need based on frequency. Instead, we focus on fire response, EMS, public education, etc., because those are the routine needs. If the response profile dictates technical rescue preparedness, then we add it to the never-ending list of skills our firefighters try to master. But for most agencies, the responsibility of technical rescue falls to a mutual aid assistance response. Perhaps the nearest metropolitan department or maybe a nearby joint response or MABAS-like team of partnerships is the best option. So, what happens when a life is literally hanging in the balance? What can you do when your only option is to wait for a response that will arrive too late? Many of us don’t have an answer for that. One of the main reasons we struggle is because our training is somewhat out of date. Of all those many things that we try to keep up with (fire, EMS, engineering, hazardous materials, leadership, forcible entry, furnace troubleshooting, and on and on) it’s very hard to stay ahead of the standards that may only loosely apply to our current responsibilities.

I’m often surprised at how many rescuers lack familiarity with National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Standard 1006, NFPA 2500, OSHA, or ANSI. They are generally aware that these exist, and some know that OSHA is law, while the others are standards, but many rescuers are still operating in a world of requirements from 10 years ago. Although most of the first-generation requirements from NFPA 1983 have faded into history, we still have many highly trained and capable teams that operate several years behind the curve. One of my favorite writers on this topic is Russel McCullar from the Mississippi State Fire Academy. He is among a few industry leaders who are willing to write what many of us are thinking: we’ve become so locked in to our initial training that we often fail to keep abreast of what’s current in the industry. As has been pointed out by McCullar, many fire-based rescuers are still hung up on safety ratios, “two-person” loads, and the requirement for G-rated equipment, despite the fact that our go-to for standards, NFPA, hasn’t published any of these requirements in well over a decade. I’d love to say this challenge will soon be gone, but we see it in every class. I don’t know if you’re aware of this, but change in the fire service is something of a challenge.

The Return of Common Sense

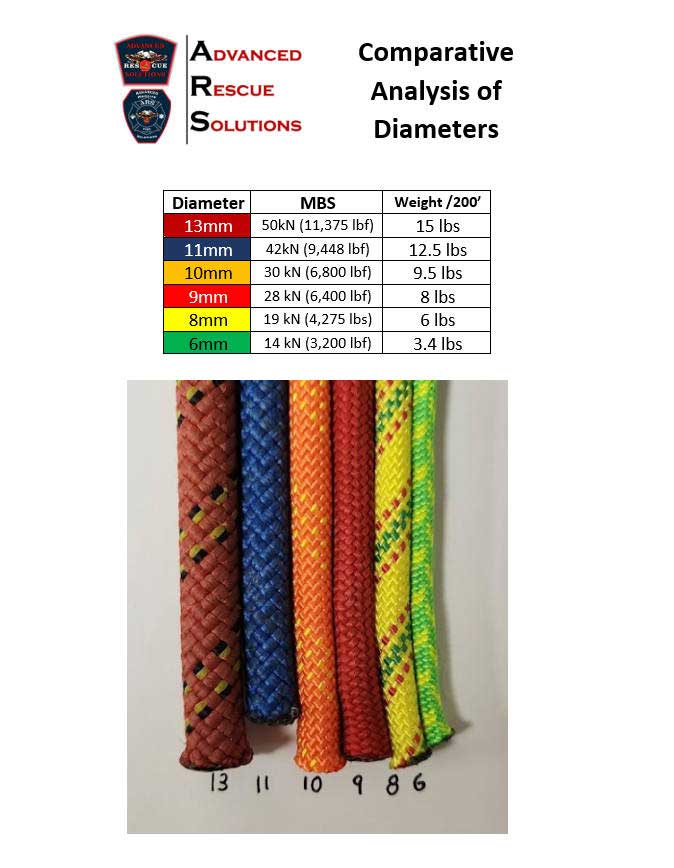

So why is this still an issue? Why are there so many teams still so deeply rooted in 13mm rope and 10:1 safety ratios while others have been using 11mm rope and focus on minimum breaking strength (MBS) for more than 10 years? Let’s look at this in a different way: when was the last time you discussed safety ratios at a vent-enter-isolate-search (VEIS) training? I’m willing to bet you only climbed up one ladder to the window, as well. Where was the redundancy in that system? On the other hand, what is a rough approximation of safety ratios that we discuss quite often in the fire service? How about the risk-benefit assessment? Ask any firefighter when we risk a lot versus when we risk very little, and you’ll get virtually the same answer from coast to coast. How are these examples of rope rescue and VEIS different? Common sense. Now don’t get me wrong, when NFPA 1983 was first published, it was all we had. Sure, it was a manufacturer’s standard, but what else could we look to? It came off the heels of a tragedy for the Fire Department of New York and, with the exception of a few cavers and rock climbers in the fire service at the time, the rest of us didn’t possess the experiences that shape our common sense. Those would come later, following years of technical rescue expansion in the 1980s and 1990s.

But even now, with 40+ years of technical rescue growth, training, testing, and empirical data, we still struggle to trust our common sense and improve our approach. Sometimes it’s a matter of equipment investment. After all, it is hard to justify a full-scale changeover if the equipment still has several years of service life remaining. Other times we can attribute the delay in change to overall exposure. Teams that send a member to conferences and classes tend to see the trends before those that stay stagnant with their initial training. But largely it’s just a matter of not being able dedicate the time to staying ahead of the curve. If you haven’t had the time to catch up on the standards, here’s the good news: the committees that oversee NFPA 1006 and 2500 allow for common sense. You as the authority having jurisdiction (AHJ, the chief of your agency) can decide what’s right for your department. Now, if your department’s standard operating guidelines and procedures need updating, it’s up to you to effect that change. No matter where you are in the organization, you can be an agent for change. It might not be easy, but nothing worth doing ever is.

So, let’s look at your comfort level with all of this. As we consider at the following scenario, know that your answers for this will largely align with one of three approaches:

- I’m not comfortable with this because it doesn’t match what I learned in my training.

- I’m 100% on board with this and don’t foresee any issues.

- I’m not sure, let me think this through a little more.

No matter where you land, take the opportunity to learn. Do the research and find the facts; that’s the only way to grow.

The Scenario

Your engine company is dispatched to an injured person at a construction site. You arrive at a bridge repair project to find a worker hanging unconscious in his fall protection. Being the astute practitioner of medical care that Mrs. Smith has come to rely on, you recognize immediately the settings for orthostatic intolerance of harness syndrome. You know that you have less than 15 minutes to get that person to the ground to avoid a high risk of fatality, and five of those minutes have already elapsed. As you assess the situation, you find that you can’t access the patient directly with ladders or an aerial, but you can access the connection point for his fall protection. You have requested the rope response, but you know they’ll take at least another 20 minutes to arrive on scene. Your backstepper mentions that he has his bailout bag on his gear with webbing and a carabiner. You formulate a plan to raise the victim’s weight off the connection on the bridge and lower him to the ground using the bailout bag. The question is: Do you proceed?

On the one hand, you have no NFPA-rated rope equipment, an 8mm rope, no service logs, and a whole host of other concerns. On the other hand, if you don’t do something, the patient will likely have a slim chance of survival. Now let’s look at the commonsense risk-benefit approach. What is the risk to you or your crew, assuming you can use fall protection already in place at the construction site? What is the risk to the patient, and would that outweigh the likely outcome of inaction? Would your backstepper hesitate to use the same equipment to bail out of a window if he was in a flashover later the same day? Would you hesitate to lower your partner from a window in a working fire? You can see, using common sense, that the equipment is designed to handle far more weight than the victim and that you trust the equipment. Please understand, I’m not lobbying for abandoning the systems in place for technical rescue responses—not by any stretch. But I am all for using common sense when a life is at risk. It’s what we do. It’s what Mrs. Smith expects of us. Are there potential risks in the scenario given? Absolutely, which is why we evaluate the risk and the benefit.

The late Mike Brown was a rescue service leader and author of Engineering Practical Rope Rescue Systems. Mike spoke of special people, special equipment, and special training in his book. Of these three, we have the people and the equipment in the scenario above, but the key is the training. Even if your agency doesn’t have a technical rescue response program, you can go out and get the training. Many times, people feel there’s no need for that effort if they’ll never be able to use the skills learned, but that’s short-sighted. As the old adage goes: “You can never learn too much about a job that can kill you.” We can always expand our knowledge and build our awareness and common sense. If you have the training, you can work through the challenges of equipment and manpower to get the job done.

To reiterate, I’m not calling for technical rescue anarchy here. If time permits, we should always wait for the appropriate response. If our training is lacking, we should not attempt something that will have a high potential of risk. If our equipment is questionable (something we refer to as loss of faith), then we shouldn’t even have it available to deploy. But armed with good training and an updated knowledge of equipment capabilities, current standards, and accepted practices, there are a great many things that we can accomplish with the tools and personnel on the first-arriving unit. And when a life is in jeopardy, why would we not employ the same level of risk acceptance that we do at a working fire? It’s a fine line between acceptable and risky. It’s our job to understand the situation, assess the risk appropriately, and use our well-developed commonsense intuitions to get the job done right.

Clinton Crafton is the deputy chief of operations with the Whitestown (IN) Fire Department. With over 30 years of fire and technical rescue experience. Clint has served in every role in the fire service, from firefighter to deputy chief, including leading the Fishers Fire Department USAR and Dive teams for more than a decade. As a 14-year member of INTF1, Clint served as a Rescue Squad Leader and Rescue Team Manager on multiple USAR deployments. Clinton has been a FDIC International HOT instructor for 11 years with the heavy vehicle extrication cadre, and now the Common-Sense Technical Rescue lead.

He can be reached at c.crafton@advancedrescue.com