By George H. Potter

Confined space rescue situations are extremely varied in nature and complexity and require numerous resources—both human and material—and well-prepared incident management. The nature of these incidents may be structural collapse; underground situations in caves, mines, or similar locations; wind energy towers; and many others. The following incident was an extremely complicated operation that combined minute-by-minute planning and execution, the mobilization of a vast array of resources, and extreme stress and tension during a 16-day duration.

In nearly every country in the world, there may be hundreds or even thousands of abandoned excavations and wells, dug primarily to search for water and, more often than not, left uncovered when water was not found. They are usually in fields and similar places that are generally not frequented by humans. However, there are far too many exceptions. One of these abandoned prospection wells is located in Totalán, Spain, a small village about 10 miles east Málaga, on the country’s southern Mediterranean coast.

Late in the morning of January 13, 2019, several families got together to prepare a mid-day picnic on one of the family’s hilly properties. Although some of the wives prepared the meals, several of the men roamed through the Fields, picking up wood for the cooking fire. One of the wives told her two-year-old son to go and get his father. As the toddler made his way toward his father, in plain sight, he suddenly disappeared into what turned out to be an abandoned water prospection well. His father ran to where the child had fallen; although he could hear the child crying, he could not see him. The 10-inch diameter hole was in fact more than 340 feet deep.

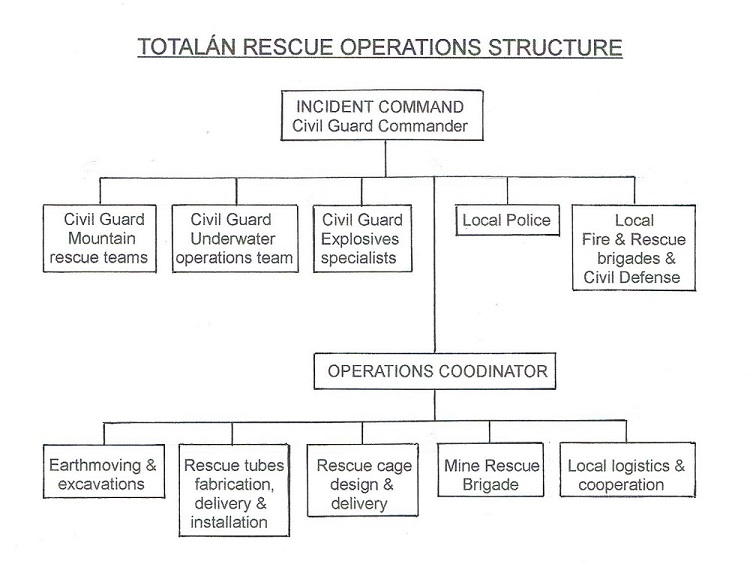

(1) The Totalán, Spain, well rescue plans.

For several hours, the adults tried to see into the hole, but nothing was visible. The child had now ceased crying. During the afternoon, local emergency response teams including firefighters from the Málaga municipal fire brigade and the surrounding provincial fire brigade, ambulance services, and local and state police responded to the site. As time went on, it became apparent that this would result in a major multiagency operation. Because the incident occured on a Sunday, resources were limited. The following day, several more agencies were mobilized, including the assignment of the head of the regional public works and roads engineers as operations coordinator. His responsibilities were principally organizing and coordinating the mobilization of numerous earth-moving vehicles and equipment and their operators,

Overall incident management was assigned to the commander of the Guardia Civil (Civil Guard—Spanish state police) in the Málaga province. Under his command were two specialized mountain rescue teams; an underwater rescue team; a specialized explosives team; and various other units including incident investigation, traffic, control and logistics.

In Spain, it is quite common that this police force assumes the direction and management of emergencies. Again, the complexity of the incident required extreme flexibility and coordination among the varied agencies and entities either on scene or contacted in other regions to supply resources and equipment. Other key operational leaders included the regional Civil Defense group and the Málaga provincial fire brigade. However, possibly the key entity in this operation was the Mine Rescue Brigade, which flew to Málaga from their base in the Asturias region, some 500 miles north. These mining accident rescue specialists finally reached the body of the child and brought him out of the well early in the morning of January 29. The autopsy performed afterward indicated that the child died almost instantly after falling into the well.

As the incident progressed, so did the mobilization of specialized earth-moving vehicles and equipment including excavators, bulldozers, and dumpers. These machines removed hundreds of tons of earth and rocks to make a working platform where the parallel rescue hole was drilled to access the child. Several long cranes were also brought to the site and were vital in drilling the parallel hole. Much of this material was brought to the site from many miles away. In all, more than 300 people were directly involved in this operation; nearly all of them remained close to the site during their rest periods.

This incident brought to light a “marvelous factor” in human nature: the ability to respond with materials and resources in extremely short times. A Málaga firefighter “had a dream” which resulted in the design of the cage used by the rescue team to descend into the rescue tubes and get to the child. These steel tubes were fabricated in record time (a few days) from request to delivery of more than 200 feet of eight-foot diameter sections that were trucked to the site.

(2) The incident’s basic operation structure.

Although the population of Totalán is a little more than 700, nearly every inhabitant participated in numerous ways behind the scenes, providing food for the personnel, housing, and other acts. A local café owner made his business the press center as dozens of journalists from all over Spain and several other countries were present during the incident.

This operation was one of the most complex emergency incidents in Spain´s history. There have been other major emergencies during the previous decades, perhaps the most serious being the multiple victim attacks on commuter trains in Madrid in 2004 that killed 193 and injured more tan 2,000. Although the emergency response and management of that incident was also complex, emergency response agencies in and around Madrid had resources available to respond and intervene.

As expressed at the beginning of the article, abandoned wells are often commonplace in many countries. The difficulties with these wells are that many are illegal and not adequately sealed-off to ensure that people or animals cannot fall into them. As a matter of fact, during the Málaga incident, news media reported other incidents in various countries; none, however, were as complicated or difficult to resolve as this one.

George H. Potter is a practicing fire protection specialist who has lived in Spain for the past 47 years. He served as an Anne Arundel County (MD) volunteer firefighter with the Riva Volunteer Fire Department and the Independent Hose Company in Annapolis and as an ambulance driver with the Wheaton (MD) Rescue Squad. He served six years in the United States Air Force as a firefighter, an apparatus driver/operator, and a crew chief. He has been involved in fire protection system installation, mobile fire apparatus design, and construction and fire safety training. He is a Spain-certified fire service instructor and a hazmat specialist, and is a member of the Board of Governors of the Spanish Firefighters’ Association (ASELF).

MORE GEORGE H. POTTER