Riders Rescued From Skyride Cars After 2 Others Fall From High Cable

features

BY

At 4:42 p.m. on the last day of the Texas State Fair, a police sergeant stepped through the door dividing the Dallas Fire Department’s fire alarm office from the police dispatch office and notified the duty officer, “The Skyride at Fair Park has fallen.” This notification was the first step in what was to be an involved rescue operation.

The fire department had, however, prepared for the possibility of emergency operations prior to the opening of the fair. Fire control and rescue companies that would respond inside the fairgrounds rechecked hydrant locations and serviceability. Pre-fire plans of the large buildings on the fairgrounds were checked and studied. A 750-gallon, 500-gpm, rapid-response, auxiliary engine was placed in service in the Fire Museum Building, formerly a fire station, directly across the street from the main gate to the fair.

This engine was equipped with biotelemetry equipment, a resuscitator, drug kit, trauma kit, and a portable radio so that it could also function as a mobile intensive care unit (MICU) in providing all emergency medical services except transportation. It was designated Engine 61 for fire suppression and rescue purposes and 761 for emergency medical purposes. Manning this apparatus were three paramedics, one of them an officer.

Medical units nearby

The designated response area for Engine 61 was limited to the fairgrounds. In addition, three MICUs are routinely stationed within 1 1/2 miles of the fair, and the State Fair Commission had contracted the services of the privately owned Professional Ambulance Service Company for first aid stations and two manned ambulances.

Before the fair opened, the fire prevention bureau had also been on the fairgrounds to handle the routine problems associated with the fair.

When the relative quiet of that Sunday afternoon last Oct. 21 was shattered by the Skyride accident, the initial Fire department response was Engine 61, two MICUs, a battalion chief, and a 100-foot aerial. Engine 61, which arrived on the scene in approximately one minute, called for two additional MICUs and went into action as 761.

As one of two deputy chiefs on duty that afternoon, I was working in my office at Station 2, about a mile from the fairgrounds, when I heard 761 on the radio calling for “two additional MICUs at the Skyride at Forest and Midway.” I immediately decided to respond, suspecting what the accident later proved to be. As I arrived at the fairgrounds, Battalion 4 was calling for two elevating platforms.

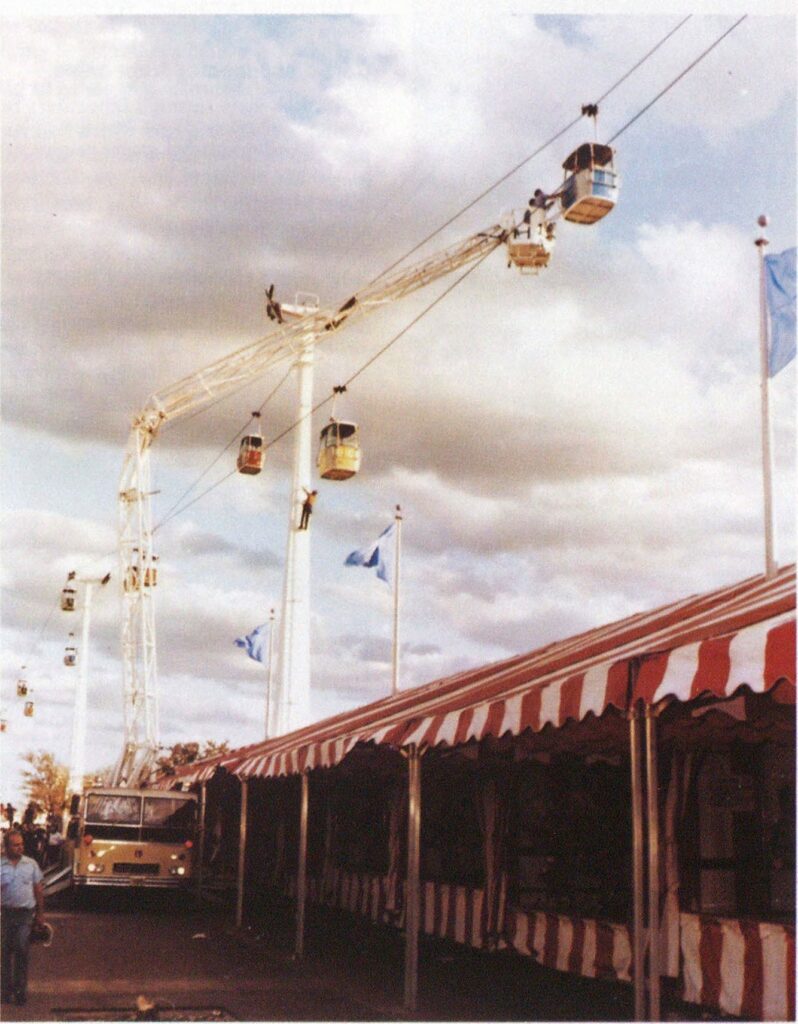

The Skyride is a people carrier which runs above the amusement park. It consists of two parallel cables, running in opposite directions and suspended at regular intervals by vertical supports through its one-half mile length. The gondolas, carrying four persons, are attached to the cables approximately 100 feet apart. There is a on-load/off-load terminal at each end of the park.

Two gondolas fall

Witnesses told us that one of the Skyride’s gondolas had stopped at the crossarm on a 90-foot tower and was rammed by a second car. When a third and fourth car hit, two cars were thrown from the cable. The cable then became dislodged from its cradle on that crossarm, dropped in a long arc, and whipped upward again. One of the two falling cars crashed through the steel-joisted roof of a concession stand. The other came to rest on the roof of the stand. The ride, and hence the cable, continued to run for a few hundred feet before the operators could shut it down.

Dallas Fire Department photos

For More Facts on Amfire, Circle No. 123 on Reply Card

A quick count at the scene showed seven paramedics working on 11 noticeably injured people. We were told that an ambulance had already transported “one load.” With two more MICUs and the EMS duty office en route, we felt that medical stabilization and transportation could be effected shortly. We learned later that night that one man died as a result of his injuries.

Our concern then turned to the people stranded in the gondolas above. The cars, running east and west, were being buffeted by a strong south wind with gusts to 35 mph and people were visible in every car in sight. Some of the riders had seen the cars fall and many more had probably felt the jolt as the cable reacted to the sudden lightening of the load and left its cradle on the crossarm. Below, they could see crowds of policemen, fire apparatus and MICUs everywhere. Controlling panic in such a tense situation was one of our priorities.

The police were an important asset in helping control the panic. They had a sufficient number of power speakers to talk to the people in the stalled cars. To be sure, it was a one-sided conversation, but there was no doubting the calming effect as policemen went from end to end of the ride and back again under the cars, telling the riders to stay calm and stay down in the cars and assuring them “You are not in danger. We will get you down soon.”

Cars disconnected from cable

A quick view through binoculars revealed that several cars which had run past the point of the accident were no longer connected to the cable but were merely hanging on it. Was there damage to any of the roller assemblies which would result in another car falling? How would the cable react should another car fall? Was the integrity of the one-piece, mile-long cable itself damaged? Fair officials and ride managers told us it could prove disastrous to attempt to start the ride—even to move the cars a few feet for accessibility.

I called for a second battalion chief and a second 100-foot aerial ladder and divided the evacuation into two sectors to work both ways down the cable. We would use the 75-foot elevating platform in the area where the riders actually witnessed the accident, believing they were probably most alarmed and would be more afraid of transferring onto an aerial ladder than into an elevating platform basket. Also, the elevating platform would be safer in the wind. The aerials would have to be used where the elevating platform would not reach.

The command post, manned by my aide and myself, remained in the clearing at Forest and Midway with visibility both ways along the cable. From this position, we would attempt to coordinate the operation.

The first obstacle encountered by fire apparatus was a row of trees centered down the opening between concession boots under the Skyride. Seven trees were removed by truck crews with chain saws and dragged out of the way. The trees had been wired for lighting, using weatherproof outlet boxes and flexible conduit. The temporary wiring had quick disconnects at the bases of the trees and the plastic fasteners were easily cut and torn loose from the trees without specialized equipment.

We moved quickly to evacuate the gondolas which had passed the accident point and lost their grip on the cable.

Three such cars, filled with children, were clustered within a few feet of each other just east of the accident scene. From one position, Truck 18, an elevating platform, was able to evacuate those cars. Each of the remaining gondolas required a separate positioning of the aerial apparatus.

The Skyride takes the gondolas diagonally over two oversize buildings, the Women’s Building and the Automobile Building. Truck 19, another elevating platform, assigned to work westward along with Trucks 3 and 4, repositioned alongside the Women’s Building and found the platform would not reach the remaining gondola over the Women’s Building. A 100-foot aerial was called into position. When the flies hit their stops, a few feet still remained between the end of the ladder and the car. We had to order the 12-foot canopy removed from three of the midway booths to give the apparatus a position to gain the additional reach needed.

In the high, center spans of the ride, the 100-foot aerials had to set almost vertically to reach two cars. We learned firsthand that if something is 85 feet in the air, a 100-foot aerial may not be able to reach it. Accessibility for positioning determines the reach.

As darkness approached, we provided for lighting but decided against using it. The grounds were lighted well enough to allow visibility up to the cars, and I believed that glaring lights, pointed upward, could increase the chance of panic.

As they were evacuated, the people from the cars were observed first by fire fighters, many of whom were EMTs or paramedics, and then turned over to fair officials for a checkup at the first aid stations. Records show that 74 persons, mostly children, were removed from the high cars. About a dozen more were removed from the lower cars near the loading platforms at both ends of the ride. Wall and roof ladders were used and, in one instance, a small bucket truck.

Rescue above roof

One woman and three children, stranded far out over the roof of the Automobile Building, were brought down to the building roof over a 16-foot roof ladder hooked to their gondola. The foot of the ladder was held by two fire fighters as a third removed the passengers one at a time. Each trip lightened the load, causing the foot of the ladder to swing higher in the air.

As we approached the end of the evacuation, working in the glow of lights from the midway, we decided to recheck our work. When the elevating platform could not reach a car, aerials were brought into position, causing the platform to hopscotch past the highest cars. Because of the hopscotching, I was concerned that we might have missed a car. After all, we had told the people in the gondolas to stay down. We could not, therefore, see or hear any who might be still up there. To be certain that everyone had been evacuated, we requested a police helicopter to scan the full length of the ride. These helicopters have both police and fire radios and powerful belly-mounted searchlights. In a matter of minutes, the copter pilot was able to give us an all clear.

The evacuation was successful, but not easy. Height and reach were difficult to judge from the ground. Obstacles in many forms denied us ready access—trees, tight corners, booths, landscaping mounds. The winds had been treacherous.

We had no real panic in any of the cars, but fear was ever present. One little girl adamantly refused for almost an hour to be helped or carried down a near-vertical aerial ladder. The entire situation was extremely tense.

While investigations into the cause of the accident will be lengthy and exhaustive, all our efforts were directed to the results of the accident, rather than trying to establish a cause.

Aid of other departments

The support we received from other city departments in responding to the accident was crucial to the success of t he operation. The police department’s assistance proved invaluable in several ways. They handled crowd control at the immediate accident scene and maintained corridors for fire department apparatus and MICUs. Their reassuring messages over power speakers were instrumental in controlling the panic and calming the people stranded in the cars. Finally, the helicopter search gave us quick assurance that all gondolas had been evacuated.

The streets and sanitation department, which also maintains emergency response teams, supported the operation with equipment, manpower, and supervision to secure the perimeters of the danger zone.

I felt a tremendous sense of pride in the members of the Dallas Fire Department as the crews accepted each challenge and demonstrated their ingenuity, determination, and training over and over again. At the same time, I was cognizant of the total resources brought to bear on the incident and thankful for the preplanned interdepartmental coordination which has become a dynamic force in Dallas’ emergency preparedness plans.