RESCUE OPERATION PLAN

THE RESCUE COMPANY

It usually starts about a week before the game. Coaches will be sent to attend the game of their upcoming opponent for the purposes of “scouting” them. They note every play, offense and defense. Special attention is given to the star players. Strengths and weaknesses of each player are important to the scouts. After all the plays and players are discussed amongst the entire coaching staff, the game film is reviewed and a game plan is formulated. The coaches now develop both offensive and defensive plans to stop their opponents. Contingency plans are added so adjustments can be made during the game. Many coaches will be seen on the sideline looking at their game plan (most of them put them in hard plastic; previous experience has shown that during some excitable moments, coaches have rolled them into a ball or even used them as guided missiles).

In the article on rescue site management, we saw how the incident commander used a game plan and made the necessary adjustments as the “game” progressed. A rescue operation plan (ROP) must be flexible so that the operations officer can make adjustments and implement the necessary tactics to control any rescue operation. The plan can be used for collapses, explosions, fires, train accidents or derailments, plane crashes, ship disasters-just about any type emergency or fire that will require a supervised, controlled, coordinated rescue effort.

A rescue operations officer (ROO) must have complete control over the rescue operation. If, upon the arrival of the operations officer, an incident commander is not on the scene, the ROO must assume overall control so that the rescue operation plan can be implemented by an officer whose knowledge and expertise will not exacerbate the situation. His responsibility to direct, supervise, and control the rescue operation, however, does not relieve him from coordinating and communicating with the incident commander, once he has arrived at the scene. Furthermore, the ROO is responsible for maintaining communications not only with the incident commander, but most importantly, with his rescue teams.

During any rescue operation, a ROO’s checklist of duties and responsibilities could probably fill one of Santa’s mail bags. But it is the ROO’s experience that will be the “crutch” needed in handling the unique problems and difficulties as they present themselves. Rescue operations generally don’t allow a ROO the luxury of using a standard form or guide to lead him through an operation, as is apt to be the case in our fire prevention and inspection activities. Being able to make adjustments is the key element oU an ROP. Let’s look at a recent major collapse and see how the rescue operations officer carried out his plan and’ made necessary adjustments where required.

It was a bright, sunny autumn day when the report of a building coilapse was received in the dispatchers office. One immediately wonders what would cause an apparently sturdy building to collapse when weather is not a factor. Investigators are finding more and more that illegal and/or unauthorized renovations have been the cause of many recent collapses, as was the case on this particular day.

The seriousness of the situation was realized immediately, since the original report was received from a fire department unit near the scene at the time of j collapse. Fire alarm dispatchers listened as a highly excited member stated that he was unable to determine how serious the situation w as because there was so much dust and plaster flying in the air that he was unable to see the building- or the remains of it-at that time. This was the start of a major rescue operation that would have a sad ending for one family but a very happy ending for many others.

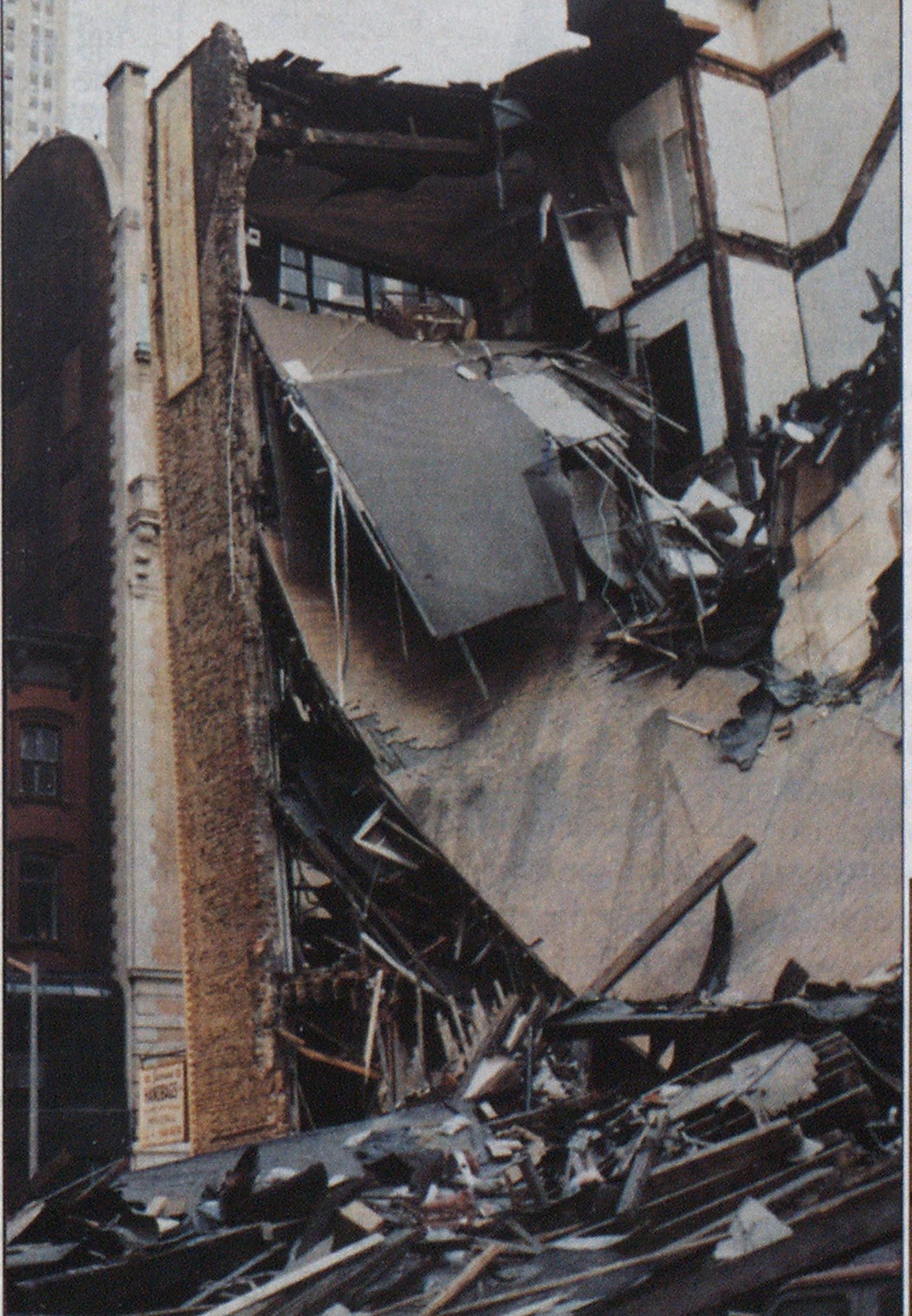

The first units arrived at the scene within minutes and w ere met by numerous people, some covered with dust and plaster, some bleeding, some hysterical, some dazed and wandering around, and others screaming for their co-workers who they thought were still in the pile of rubble that once was a six-story, brick-and-joist building.

The most apparent problem, one that would take a great amount of effort and coordination, was to determine how many victims could possibly be in the collapsed building.

Arriving shortly after the first units, the incident commander (a deputy chief) established a command post, initiating an operation that was to last more than 8½ hours before the last survivor was brought out. As additional chiefs and companies arrived, assignments were given to cover the rescue operation, victim control and coordination, safety, communications, water supply, and interagency liaison (police, utilities, buildings, etc.), and so the incident command system was established.

SIX-SIDED APPROACH

The ROO set the game plan into operation. The most accessible locations were addressed first. As additional rescue companies arrived, they were assigned to priority areas of the collapse. The three rescue companies were strategically positioned to provide a “six-sided” approach from above, below, and each of the four sides.

It must be remembered during these types of large-scale operations that the ROO will be responsible for directing and controlling the operations of the rescue personnel, and that all communications, requests, directions, and information must be channeled through him. At large-scale operations, there may be anywhere from 20 to 50 portable radios in operation, and rescue teams should use a secondary channel to avoid interference from other communications in effect. The ROO should have by his side another member with a portable radio who will stay on the primary channel and maintain communications with the command post.

Photos by Jim lorizzo.

This building was unsupported by other buildings and had collapsed into a parking lot on the exposure 4 side, covering a number of automobiles. The remainder of the structure left standing was highly unstable. The initial rescue operation was centered on the top of the pile of rubble where the upper floors had landed in a leanto position, creating a few voids. Rescue personnel entered these voids and, using the “call-and-listen” approach (“call”: calling out and asking “if anyone is in there” or “can you hear us?’’; “listen”: after calling, listening for a response), made contact with two trapped building occupants. The voices of these trapped workers gave the rescuers a point of direction to guide their rescue efforts. The ROO directed other members of the rescue teams to look for similar voids from the six sides. Their efforts proved negative.

The ROO notified the command post of the rescue effort in process and requested medical personnel to be ready to treat the trapped civilians. Tools and equipment were readied for possible use. A staging area was designated, separate from the command post staging areas, that was to be used for rescue equipment and personnel by the ROO.

Due to the instability of the remaining structure and the position of the debris, orders were given that power tools were not to be used; any vibrations or unnecessary movements could have caused further collapse. Hand-by-hand digging and careful removal of all debris and obstacles was in order. Minimum manpower was committed to the collapse area so as not to create an overload.

Extreme care was taken during debris removal while trying to reach trapped victims. Moving the wrong beam or supporting member could have caused an avalanche of debris, possibly adding to the rescue effort. This was one of the most critical aspects of the rescue operation and reinforces the importance of using only experienced personnel in these situations. Another consideration in this particular incident was the vibration that could occur from underground subway and rail traffic in the area. A request was made to the agencies involved to shut down all service.

As rescuers were making their way to the trapped workers, the ROO placed additional rescue personnel on standby status, just out of the collapse zone (the area that could be covered by the falling debris in the event that the remaining structure collapsed). Too often the safety of the rescuers is taken for granted.

What if? Another part of the checklist. “What ifs” could fill a page. But what if the rescuer in this incident did get trapped? (It happened recently in a large city, but fortunately it had a happy ending). The ROO had to take that possibility into account. It’s not unusual for the “computer” (the one we speak about often-the one under the helmet) to go into the overload stage during these types of operations, The most experienced rescue officer will tell you that after a “self-critique” he usually can think of a number of items that might not have been on his “printout” that particular day.

After rescue personnel reached the trapped victims, stretchers were called for, the victims were secured into them, and a chain of rescuers safely removed them from the collapsed building. Rescue of these two victims was accomplished in less than an hour from the time of collapse.

While the rescue efforts were taking place, the ROO requested from the incident commander any further information regarding the possibility of additional victims trapped under the huge pile of rubble.

REASSESSMENT

It was while this information was being sought that a combination of factors dictated the removal of all rescue personnel from atop the pile while an assessment of conditions was undertaken:

- The continuous “call-and-listen” procedure was now getting negative results. It should be noted that the victim who was trapped for 8½ hours stated in an interview a few days later that she could hear the voices of rescuers and kept calling out for help. Her calls were muffled by the debris (as high as eight feet in some places) and therefore went unanswered.

- The remaining structure was highly unstable. The heroic initial rescue of the first two trapped building occupants had taken place under extremely dangerous conditions. A survey by the building commissioner reinforced the decision to remove rescue personnel from the pile. Structural instability was the primary reason for this decision.

These factors required the reevaluation and reassessment of the rescue operation plan. Rescue personnel were directed to the operations staging area, while a conference among all agencies involved was held at the incident command post to determine alternative actions to be incorporated into the game plan.

The number one priority would be to try and ascertain the number of occupants-and if, indeed, there were any-still unaccounted for. All survivors, either still at the scene or at hospitals, were interviewed. This required a coordinated, teamwork approach from all agencies involved. The information gathered indicated that there had been 11 people in the building at the time of collapse. Two had to be removed via a tower ladder from the front section, a few had reached safety via the rear, and the remainder had ridden the collapse down into the parking lot like a giant slide. A victim control coordinator ordered personnel to visit the survivors at the hospital, and this proved extremely helpful in finalizing an accurate count of missing victims. These interviews, plus those of eye witnesses, occupants of neighboring buildings, and others familiar with the daily activities of the occupants, helped in the final determination that two victims were still unaccounted for.

However, one uncertainty that remained throughout the operation was another “what if’-what if someone was visiting, delivering a package, or just happened to be passing by when the collapse occurred? This uncertainty was dealt with as the operation proceeded; fortunately, no “what if’ victims were found. This is the kind of item that the “computer” doesn’t always have the answer to.

When interviewing the survivors, certain information can be crucial in locating the missing victims. Where .were they last seen? Where do they work-on what floor, and at the front, middle, or rear of the building? What’s the normal layout of the floor? Did they exhibit any particular work habits? Do they work at the same location all the time, or do they travel to different areas of the building? Trying to place them just prior to the collapse and then “reading” the collapse rubble to pinpoint location can be extremely helpful. This operation was proof positive that the interview method can be successful in building collapse rescue operations.

“PROACTION”

In a “proactive” decision, the incident commander, taking reflex time into account, had requested that a crane be moved to the scene. Furthermore, a building department employee was requested to monitor the building continuously with a surveyor’s transit for any signs of further building movement that could forecast collapse; a firefighter with a portable radio was stationed with him. After rescue workers had been ordered from the pile, the crane was placed into operation. The crane operator drew high praise for his surgeon-like removal of the remaining front of the structure. As the crane worked, lighting was placed so that night was turned into day.

The interagency conference focused on the next part of the game plan. It was decided to separate the collapsed area into manageable sectors. Each sector would be commanded by a rescue team leader, with the ROO in overall coordination command. Deploying the rescue teams in such fashion would give the rescue effort greater coverage.

A number of preparations had to be initiated prior to implementing the operational plan. Reaffirmation of utilities (gas, electric, and water) shutdown was requested. An accumulation of gas sparked by a short circuit in an electrical line could have been worse than the original collapse. The possibility that a broken water line filling the cellar and undermining the remaining structure had to be considered.

A briefing session with rescue team leaders and members discussing the operational plan was held while the crane work continued. Areas to be searched, based on all the information gathered, was plotted out. This proved to be a great assistance in locating one of the survivors. The building had collapsed and landed, surprisingly, almost in floor order; that is, as the floors settled in the parking lot, the roof area was on top of the pile, with the 6th-, 5th-, and 4thfloor ceilings and floorings directly underneath, in order.

ADDITIONAL MANPOWER

The ROO, anticipating a prolonged rescue operation, requested that additional manpower be made available, that sufficient equipment and tools be brought to the staging area, that medical personnel be alerted and placed on standby, and that the necessary lighting was in place.

After the crane operator had successfully picked apart the front wall of the structure-thereby removing the most imminent threat to safety-special “sniffing” dogs, listening devices, and a thermal imaging camera were used in the search for the remaining victims, but to no avail. It was decided during the strategy conferences that, because of the possibility of the victims still being alive, heavy power equipment such as bulldozers and backhoes would not be used, and that hand-by-hand digging and debris removal would be continued.

When considering victim survivability, the “Golden Day” is to collapse situations as the “Golden Hour” is to vehicle accident victims. As a general rule, medical attention within 60 minutes of a serious vehicle accident must be achieved in order to increase the chances of victim survival. New data based on major earthquake disaster information indicates that a collapse victim’s chances for survival are much higher if rescued within the first 24 hours after the disaster- hence the term “Golden Day” (See Response Magazine, March/April 1987).

Rescuers formed long human chains, and debris was passed from man to man, by hand. It was necessary at one point to stop operations so that a power saw could be used to cut through some obstacles that were hindering the operation. Prior to using the saws, the area to be cut was carefully cleared and checked to ensure that a victim would not be accidentally cut. These power saws were used on a very limited basis. Soon after, the hand-to-hand debris removal continued.

After approximately four feet of debris had been removed from an area near the section of roofing, rescuers located the body of the building owner. Before the rescuers got the chance to feel discouraged, however, another rescuer loudly announced that he had found a conscious victim.

At this point, extreme care was taken. Overanxious rescuers could further complicate the rescue effort if total control is not maintained. It is paramount, therefore, for the ROO to take control, firsthand. Surprisingly, the surviving victim was conscious and able to converse with her rescuers as the effort to free her continued. She told them that she had been sitting at her desk on the 6th floor when, suddenly, everything seemed to break apart; she started to fall, as did the floor beneath her. She actually rode the collapsing floor down until it landed in the adjoining parking lot. Her fall was cushioned, and she was completely protected by cases and boxes of novelty items that were stored on the upper floors. The protection from these boxes saved her from any crushing injuries from building components. A miracle, or just another “what if?

Constant chit-chat between the victim and rescuers helped to pass what seemed like a lifetime as medical personnel evaluated her condition and stabilized her prior to final removal from entrapment. Hundreds of boxes had to be removed to completely free her body so that a stokes basket could be placed into the hole made by the digging. Tired rescue workers received a fresh breath of enthusiasm as the realization set in that this victim would survive, and a feeling of great satisfaction was evident throughout the entire rescue scene.

The possibility still existed that the “what if’ victims could be in the pile. Another interagency conference was held, and discussion centered around this possibility. Flans were formulated for a continued rescue effort that would include the use of power equipment and last for a number of days. It was felt that, after 8½ hours during which no other occupants, workers, or civilians from this area were reported missing by their families, the continuing rescue effort would prove negative. It did.

Media coverage was an important factor. TV and radio coverage was extensive, and feelings were that if someone who worked in or around the collapse building area had not returned home, their family would have contacted someone at the scene.

CRITIQUE

After the operation was completed, a debriefing session was held but, due to the amount of media coverage, a complete critique and analysis of the operation could not be held at that time. A few days later, a formal critique was held by the incident commander. Photos, slides, and tapes were reviewed and the consensus from rescue personnel was that although the rescue effort was a sue*, cess, there was a wealth of lessons learned that could enhance futurerescue operations. Adjusting thq| “game plan” and updating the “computer” (yes, the same one) has to be part of the ROO strategies.

Let’s review some of the duties of the rescue operations officer that re-quire his immediate attention while* trying to implement all the operational procedures necessary to bring sucha complex rescue operation to a sue, cessful conclusion:

- Direct the rescue operation.

- Designate team leaders.

- Supervise, control, and direct the rescue team and team leaders.

- Divide the collapse area into manageable sectors.

- Assess and evaluate the game plan as it plays out.

- Have a contingency plan on standby

- Gather information, collate it, and feed the “computer.”

- Maintain communications-“laterally” to rescue teams/team leaders and “up” to incident commander.

- Designate staging area-equipment, tools, and manpower.

- When time allows, run through the checklist -utilities, medical personnel, additional equipment and manpower, lighting, etc.

- Keep Incident Commander updated as to progress.

Just like a winning coach, the ROO must implement his “game plan,” use his “computer,” utilize the strategies and tactics he has incorporated in the ROP, and make the necessary adjustments. If he does so, he will have added another win to the team record *