By Tom Guns and Dennis L. Rubin

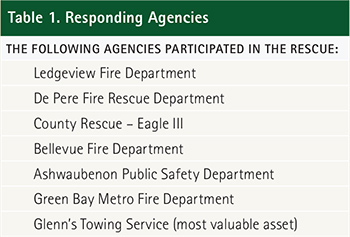

A request was transmitted over the Brown County (WI) Radio Communications 800 MHz fire frequency to send assistance for a “tractor overturned on a man at 3875 Dickinson Road.” This brief request from Ledgeview (WI) Fire Department (LFD) Engine 1811 was the beginning of an extended extrication that would take a half-dozen fire and public safety agencies to resolve (Table 1). The initial dispatch was for the LFD along with De Pere (WI) Fire Rescue Department (DPFRD) Ambulance 121 (paramedic), Engine 111, and Chief 101. Sometimes, initial dispatch information can be a bit limited, based on the information the Dispatch Center receives. Often, the event turns out to be quite different from what was expected or described. This response was more difficult to resolve than expected.

Before this extrication operation was completed and the patient flown out to definitive medical care, the regional fire-rescue services were tested to nearly the breaking point. Six departments had to pool their personnel, apparatus, and equipment. It took everyone working together for just under two hours to free the man from the rolled-over and crushed John Deere 9360 tractor.

The Initial Operation Begins

On arrival, LFD Engine 1811 was confronted with a very difficult and complex situation. As we sized up the situation, we quickly realized that this was no ordinary farm equipment rescue. Based on the limited dispatch information given to our Communications Center, the prevailing belief was that a standard field-size farming tractor (perhaps a John Deere E3) had rolled over in a crop field and pinned the operator’s arm or leg. When we arrived on location, however, we saw that the tractor was one of the largest that the John Deere Company manufactures; it weighed an impressive 60,000 pounds.

![(1) The driver's compartment of the John Deere 9360 tractor. [Photos courtesy of the De Pere (WI) Fire Rescue Department.]](https://emberly.fireengineering.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/1509FE_RubinPhoto1.jpg) |

| (1) The driver’s compartment of the John Deere 9360 tractor. [Photos courtesy of the De Pere (WI) Fire Rescue Department.] |

This machine flipped over at the top of a 45-foot-high, banked earthen wall. The device slid down the wall of the basin to the flat surface at the bottom. At the time of the accident, the tractor was engaged in constructing a large manure-retention pit. When this super-sized tractor came to rest, the operator was inside the upside-down cab and severely entangled from the waist down.

The earth under and around the familiar green and yellow John Deere eight-wheeled gigantic tractor was soft and freshly disturbed. The earthen walls around the manure pit could slough off and cover the rescuers with tons of loose dirt at any time. All of these points were critical size-up factors that added a high degree of difficulty. Each factor had to be considered at this extended extraction operation and the appropriate controls had to be incorporated into the incident action plan (IAP).

DPFRD Engine 111 (east side station) and DPFRD Ambulance 121 (west side station) reported on location next. The response objective was to reach the trapped and entangled occupant to provide critical, immediate lifesaving care: provide airway support with oxygen, control bleeding as much as possible, deliver blood volume expanders, and administer pain-control medication.

|

| (2) The four-point stabilization system included a backhoe, two wreckers, and a John Deere 9360 tractor. |

DPFRD’s Chief 101 arrived next. He assumed the initial incident command position until he was relieved by Chief Tom Guns from LFD. The IAP, as immediately implemented, was simple and straightforward:

- Stabilize the tractor, keep the victim from further harm, and prevent injuries to the firefighters.

- Provide lifesaving medical care to the trapped and entangled victim.

- Determine what resources were needed to resolve this situation, and get the rescue “cavalry” rolling toward the scene.

The complete and ongoing work plan included the following components:

- Ensure scene safety for operating companies.

- Evacuate all farm workers and other by-standers from the immediate work area.

- Deny public access to the rescue work area; establish a hazard zone perimeter.

- Continue to size up and obtain intelligence from the work area.

- Determine the additional personnel and equipment needed, and call for it.

- Stabilize the tractor and the surrounding work zone.

- Access the patient to provide advanced life support (ALS) care and pain management medications.

- Disentangle and extricate the entrapped patient.

- Rapidly treat the patient and helicopter transport him to the trauma center.

- Render the scene safe postevent (flip the tractor back on its wheels).

- Conduct critical incident stress debriefing of all responders.

- Provide rest, rehabilitation, and fluid replacement for responders.

- Service and clean the equipment.

- Prepare the companies for the next response.

(3) De Pere firefighters prepare an IV for the trapped victim.

An Unexpected Twist

As the LFD and DPFRD companies were setting up operations, the identity of the trapped man was revealed. As fate would have it, the farmhand and tractor driver was a captain in the LFD. The concept of a clinical problem-solving approach to this complex extrication was challenged. Every member of the LFD knew and respected their captain. Further, most of the encased victim’s immediate family members are active firefighters in this company. About a half dozen other close relatives live nearby; all of them arrived shortly after the fire department’s arrival.

The close relatives in the department had their turnout gear donned and went to work to help remove their loved one from the 60,000 pounds of wreckage. The many other family members observing the operation had a keen understanding of the gravity of the situation based on being associated with the department for years. The proximity of the family escalated the stress level.

The Extrication Operation Ratchets Up

We requested additional personnel and extrication equipment. Since entry into the upside-down tractor cab (photo 1) was needed to access the patient for treatment and removal, it was critical to stabilize the “vehicle.” We called for two wreckers-one jumbo size and the other regular size-to focus on preventing the tractor from slipping or moving any farther. As more fire companies were being dispatched, DPFRD Chief 103 (medical director-emergency physician) radioed Command that he was en route and would assist with on-scene medical treatment. Command and the medical director determined that an aero-ambulance was needed; the Eagle III county rescue from Green Bay was requested. About 15 minutes later, the American Eurocopter EC-135 helicopter was circling the incident scene preparing to land and go into a cold shutdown while waiting for the patient.

|

| (4) Cribbing stabilizes the tractor. |

As more personnel arrived, the command organizational chart started to fill out, and the work to remove the trapped farmer was progressing. Two more engine companies (one a rescue engine) were summoned from Bellevue. The revised IAP contained the same three basic objectives and additional items. The fire department chaplain was requested to assist with the family members. The pastor comforted and communicated with the growing number of family members on location. Their presence presented a challenge in that some were active members of the fire company and insisted on helping with the operation.

Engine 1811 was assigned to hazard control and fire mitigation. A 1¾-inch handline was moved into position and charged to protect the trapped occupant and the firefighters who were deep inside the tractor cab providing medical care and working toward extricating the entangled off-duty fire captain. A four-point stabilization system was developed; it included a backhoe, a jumbo wrecker, a regular roll-back wrecker (both tow trucks), and a second John Deere 9360 tractor (photo 2).

When the fire department arrived, the bucket of the backhoe was placed on the downhill side on the flipped tractor to prevent it from sliding. This was the first anchor point, and it was maintained throughout the extrication.

Next, the plan included moving the largest wrecker to the front of the upside-down tractor. The first set of hoisting cables was attached to the axle and frame toward the front of the vehicle. Then, the regular size wrecker was attached to the mid-section of the tractor. Once again, the frame rails made an effective attachment point. The regular size wrecker was moved to the very top of the ridge (near the area where the tractor likely skidded down about 30 minutes before). The regular wrecker was a fraction of the weight and “footprint” of the tractor. To make this operation safe, the wrecker traveled on the backside of the “mountain” of earth to ensure that the soil would not be disturbed and prevent an earth slide toward the dozens of firefighters working diligently to extricate the victim.

|

| (5) Personnel work to extricate the trapped victim. The operation took nearly two hours. |

The last anchor point was the rear of the vehicle. This attachment was simple and basic. The second 9360 tractor used a five-inch nylon sling strap to hold tension on the rear quad tires of this massive machine. Once all four anchor points were in place, the cribbing, digging, and lifting continued. Using this system, the crushed tractor was stabilized to a reasonable degree and didn’t slide any farther. Access to the patient for treatment and extrication was made safer at this point (photo 3). The extrication and treatment groups understood that the flipped vehicle could move in any direction and potentially fatally injure the rescuers.

The extrication group was under the leadership of Captain Edwin Balcer from DPFRD, a 25-year veteran of the Wisconsin fire service. In a major, protracted, and difficult operation, everyone determines success or failure. It is unusual to single out just one individual. However, Balcer’s bravery, skills, knowledge, and abilities were outstanding on this day. He will be nominated for various state and national heroism awards based on his work at this incident.

The jumbo wrecker continued to raise the tractor in a nearly straight line. With each four inches of upward movement provided by the crane, the extrication team placed the next row of four-inch × four-inch wooden cribbing in place (photo 4). This would secure the position of the raised tractor and prevent it from falling on the rescuers. This was a slow, crude, labor-intensive, and very difficult process. There was no way to hurry the lifting aspect of the rescue and ensure a reasonable degree of rescuer safety.

While the lift was taking place, ALS care was being rendered to the victim under the supervisor of Dr. Stroman as much as the confined area and overall situation allowed. The goal was to remove the trapped occupant as quickly as possible while not compromising the safety of the rescue workers (photo 5).

|

| (6) An overview of the hard zone. |

It took nearly two hours of lifting, shoring, and repeating the process to free the trapped victim from his farm tractor. At the same time, the four-point stabilizing system had to be evaluated; tension had to be maintained to provide as safe a working environment as possible. Once removed from the overturned 60,000-pound farm tractor, the victim was carried to the waiting ambulance. The ambulance moved the victim to the plateau, where he was loaded aboard the waiting county helicopter and taken to the trauma center. He was delivered to the receiving facility conscious and breathing with reasonable vital signs considering the ordeal that he endured for the past 119 minutes. At the time this article is being written, he is reported to be in stable, but critical, condition. Everyone in all six fire departments is praying for a full and rapid recovery.

During the lengthy extrication process, the fire department’s chaplain stayed with the distressed family members attempting to provide comfort and explain the unfolding operation. The family members were transported to the trauma center by ambulance so they could be with their injured loved one. The ambulance crew helped and cared for the family members as the captain was wheeled off to surgery.

Demobilization and Recovery Process

When the patient was removed and on the way to the hospital, the next phase of the action plan was implemented. The Wisconsin Occupational Safety and Health Administration was notified of the workplace accident before the cleanup operation began. It said there would be no on-scene investigation because of the size of the farm. It would follow up with the responding departments when time and resources allowed. The operation was cleared to start the demobilization process.

The next objective was to remove all of the loose equipment and hand tools from the hazard zone (photo 6). To expedite this process, all medical- and rescue-related equipment (regardless of who owned it) was collected and piled into two pickup trucks. The trucks were off-loaded at DPFRD Fire Station 1 for cleaning, servicing, and sorting. All items were returned to their proper owners by nightfall. Once the area was clear of all fire department equipment, the jumbo wrecker flipped the destroyed tractor over on its wheels. Once the tractor was righted, we were amazed to see how small the crushed space was in which the tractor operator was trapped for such a long time.

As the final cleanup was completed, we noted that two rescuers did not recover completely. They were transported to an area hospital for treatment of dehydration and were released that evening. At last check, both made full recoveries and are ready to go back to firefighting duties.

Critical Incident Stress Management

The regional Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) team was summoned to the location to check our members. After completing on-scene welfare checks, the CISM team relocated to the affected fire stations and conducted a formal defusing process. A follow-up session is planned. Responders received information on how to access confidential mental health relief and support from fire department members. Interestingly, as the CISM team started to check on our responders, an alarm for a house fire was received. The DPFRD had a room-and-contents fire to resolve before finishing the CISM process. As in every aspect of the fire service, the beat goes on, and we are obligated to work at the customer’s pace. After the extinguishment of the kitchen fire with the help of the Green Bay and Howard Fire Departments, the recovery process for personnel and equipment was completed.

This was a major, extended operation that had a successful ending. The trapped occupant was extricated while still conscious and breathing. Only time will tell what the final level of his recovery and quality of life will be.

Two minor firefighter injuries were sustained; both firefighters were treated and released from the hospital the same evening. Perhaps more firefighter rehabilitation will be needed to avoid similar injuries in the future. The use of the helicopter was appropriate and necessary for the circumstances. Being able to load the patient and have him at the trauma hospital for definitive medical care in minutes was an important step in the “survival chain.”

Finally, the Mutual Aid Box Alarm System (MABAS) worked amazingly well, even better than advertised, to resolve this incident. Six separate and independent departments worked effectively and efficiently alongside a competent local towing company as one force to move a 60,000-pound object off the entangled tractor operator. The interface among the departments was seamless based on the region’s MABAS. MABAS makes it seem as though Brown County is one single operational department.

TOM GUNS is chief of the Ledgeview (WI) Fire Department (LFD), which he joined in 1992. He served eight years as a paid on-call member of the De Pere (WI) Fire Rescue Department.

DENNIS L. RUBIN is chief of the De Pere (WI) Fire Rescue Department and a principal partner in the fire protection consulting firm D. L. Rubin & Associates. He is a 35-year veteran of the fire service. He has a BS degree in fire administration from the University of Maryland and an AAS degree in fire science management from the Northern Virginia Community College. He is a graduate of the National Fire Academy (NFA) Executive Fire Officers Program and the Naval Post Graduate School’s Executive Leadership course in Homeland Security. He is a certified emergency manager and a Center for Public Safety Excellence-designated chief fire officer (inactive) and a chief medical officer. He has been an adjunct faculty member at several state fire-rescue training agencies and the NFA. He is the author of Rube’s Rules for Survival, Rube’s Rules for Leadership, and D.C. FIRE.

Unified Command, Mutual Aid Key in Garage Collapse

Rollover Extrication: Upside Down with Nowhere to Go

Tractor Rollover Rescue