Planning Mass Evacuation Before Disaster Occurs

features

CHIEF

A great deal has been written in the past few years about the strategy and tactics necessary for handling a hazardous materials incident. Yet, one aspect of the overall requirement has, unfortunately, been neglected. This area involves the evacuation of citizens as a result of a hazardous materials incident.

The major reason for neglecting this area is that very few studies have been done on the planning and implementing of evacuation programs. As a result, municipal officials tend to relegate evacuation planning to some future project when more pressing needs have been taken care of. Unfortunately, there always is some major project and an evacuation plan is never formulated. This article is an attempt to summarize the present knowledge of evacuation planning and explain why the fire service leaders of a community should undertake the responsibility for plan development.

The major work in the area of evacuations has revolved around potential radiation problems from nuclear power plants. Within the atomic power plant licensing process, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission requires an evaluation of the consequences of a series of simulated accidents. The applicants must submit details for coping with emergencies and accidents which could affect members of the public around power plants.

Little data available

One way for the general population to be protected from a nuclear power plant accident is to move persons outside the boundaries of the potentially affected geographic area. Obviously, this same protection is needed at a hazardous chemicals incident. Since there has been only one power plant accident in which evacuation was even considered, there is very little data available on the problems which could be encountered.

For this reason, all the nuclear evacuation research has focused on other natural and man-made disasters. We, in the fire service, can make use of this information to formulate our own evacuation plans.

One of the most useful studies on evacuation was performed by the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Radiation entitled, “Evacuation Risks—An Evaluation.”1 Its objectives were to determine:

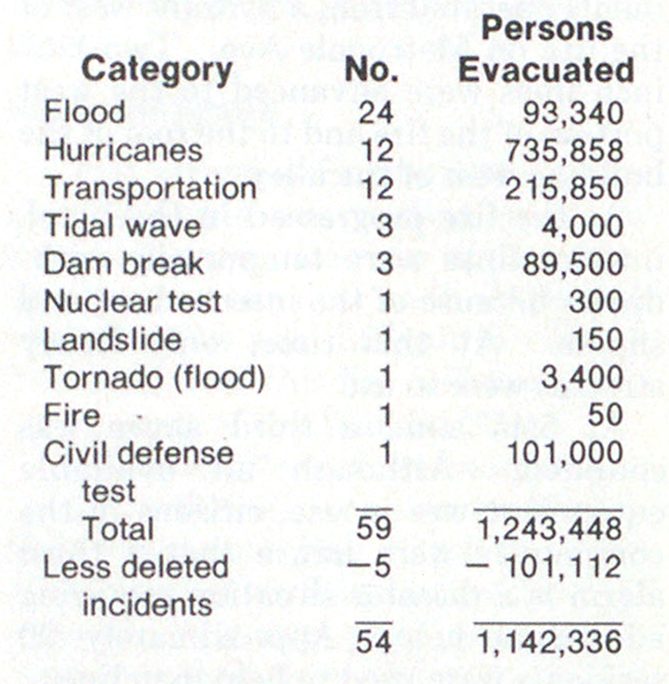

Table 1—Evacuation Incidents

“The risk of death, major injury, and cost associated with an evacuation; what parameters in an evacuation affect risk; and, if such parameters exist, can they be used to prognosticate risk.”

Disasters reviewed

Because there is no national clearing house for disasters, the EPA study compiled a list of those United States disasters between 1960 and 1973 which required an evacuation of 25 or more individuals. This list was developed by a literature search for references and by contact with national trade associations and federal, state, and local governments.

Overall, a list of about 500 events was compiled, involving many different causes—floods, fires, hurricanes, explosions, and hazardous materials incidents.

Taking the list of 500 events the authors of the study attempted to gather additional information. Parameters such as weather, time, and road conditions were needed for each event as well as information on deaths, injuries and costs. Of the initial 500 incidents on the list, 59 were selected for detailed analysis. The selection was based upon the ability of the researchers to gather the required data. However, “All transportation accidents involving hazardous materials and an evacuation of more than 500 persons were investigated since it was thought their occurrence without warning would more closely approximate reactor warnings.”2

Subsequent to the selection of the 59 events for further study, five were eliminated because of the lack of sufficient data. This left 54 incidents which were carefully studied. A summary of the incidents is shown in table 1.

Death and injury risk

Of all the events studies, involving an evacuation of 1,142,336 persons, there were few deaths attributed to the evacuation process. It is important at this point to emphasize that these deaths were a result of only the evacuation and not the incident. The incidents and circumstances under which the deaths occurred are detailed in table 2.

There were only two injuries reported in the evacuation of 1,142,336 persons. These two are detailed in table 2.

Evacuation risks

The potential risks as a result of an evacuation are dependent on many factors including:

Agent (flood, hazardous materials incident, earthquake).

Number of persons to be evacuated.

Size of the area.

Type of area (rural, urban, suburban).

Evacuation method (automobile, bus, boat).

Types of roads.

Length of evacuation route.

Weather conditions.

Road conditions.

Availability of evacuation plans.

Time between incident and evacuation.

Time required to evacuate.

Time people are kept out of the area.

Since there were so few deaths (10) and injuries (2) the EPA report does not make a conclusion about the risk of death as a result of an evacuation. However, it does appear that the expected death and injury rate would be low in an evacuation.

Accident rates compared

Almost all the evacuation was done by automobile (99 percent). A comparison was made between the national motor vehicle death rate and the two automobile deaths (drownings) encountered during an evacuation. The comparison shows that:3

“The risk of death per person-mile would be four times higher during an evacuation than the death rate during normal driving conditions.”

The study also makes a comparison between the daily death rate from all acidents and the daily death rate per 100,000 persons in the evacuation. The study concludes that the rates for evacuation-caused accidents are three to six times higher than the national figures.

Table 2—Deaths and Injuries During Evacuation

Because there were only two injuries, no prediction of the injury rate during an evacuation could be made. For purposes of estimating non-fatal injuries, planners should use the Figure 2.7 per 100,000 persons per day.

Evacuation problems

By reviewing the problems actually encountered in past evacuations, fire department officials can include procedures for handling them in their plans. These problems include:

Premature childbirth.

- Traffic congestion.

- Rush to gas up vehicles.

- Rush to stock up on food.

- Security to ensure access of needed individuals to areas while preventing unnecessary people from entering.

- Information to evacuees on estimated time they can return to impacted area.

- Reluctance to leave area because of (a) curiosity to see the incident first hand or (b) concern about abandoning their home. (The study estimated that approximately 6 percent of the population refused to evacuate.)

- Sightseeing of aircraft over impact area. (The Federal Aviation Administration can be requested to close the air space over the impacted area.)

- Breakdown of private vehicles, since this is the primary means of travel. These would include accidents, mechanical problems, and lack of gasoline. (More than 99 percent of the evacuees of the incidents studied used private vehicles.)4

- Non-English speaking population group.

- Overresponse of volunteers from private organizations that created logistics problems.

- Relatively few people use the evacuation centers, preferring to find accommodations with friends, relatives, or in commercial establishments.

- Inability to account for the evacuees since so few use the evacuation centers.

- Evacuation of special facilities, such as hospitals, nursing homes, schools and penal institutions.

- Separation of families during the evacuation (children at school, husband

- and wife at work, and separation in traffic).

Evacuation warnings have been issued through newspapers, television, radio, telephone, public address systems mounted on vehicles, and by doorknocking. While the newspapers are fine for a slow-moving incident, in a hazardous materials incident, the information must be disseminated quickly.5,6

Time range

Within the incidents studied, the evacuation time ranged from approximately 2 to 18 hours. One of the major factors in determining how quickly the evacuation can occur is population density. As the density decreases (population scattered over a greater area) the evacuation time increases. Figure 1 shows the population density versus evacuation time for the incidents studied.

Some of the reasons postulated for this increase in time are:

- Warning times increase because the population is scattered and has to be reached by direct contact.

- If shutdown of farms is necessary, extra time must be spent.

- Road networks in rural areas generally provided a limited choice of roads and direction of travel.

Statistics which have been observed during an evacuation and which could be helpful in the planning process are:

- Approximately 2600 cars per lane per hour can be accommodated.7

- The average vehicle occupancy is four persons.7

- If 2600 cars containing four persons can be accommodated by one road lane, then 10,000 persons can be evacuated per lane per hour.8

Avert problems by planning

In developing an evacuation plan, many problems can be avoided by giving consideration to the following:

- Keep the plan as simple as possible, using language at the level of the user of a particular portion of the plan.

- Conduct drills utilizing the plan and make the necessary corrections.

- Make sure that the plan takes into account people’s behavior patterns, covering such areas as reluctance to leave the home and hoarding of food and fuel.

- Ensure that all agencies mentioned in the plan are aware of their responsibilities.

- Ensure that individuals who have specific responsibilities have backup people in case they are not available.

- Arrangements should be made for the evacuation of the families of the emergency response personnel, who will be busy at the incident. They need to be able to devote full time to the emergency without being concerned for the safety of their families.

- Training, training, and more training in the specific tasks each individual must perform.

- Include a section in the overall emergency medical services plan on handling medical emergencies created solely by the evacuation. This would include handling childbirth emergencies, heart attacks, and vehicle accident injuries. An additional section must also include the procedures for evacuating hospitals and nursing homes.

- Prepare a plan for the printing and issuing of various levels of passes into the evacuated area.

- Include a section in the plan for dealing with air traffic and the requirements for restricting the air space adjacent to the incident.

- A force of public and private tow vehicles needs to be mobilized to handle breakdowns and accidents. It is im-

- portant to keep the roads open, and the tow trucks will plan an important part.

- A list of interpreters who can provide instruction to non-English speaking evacuees will be necessary. In addition, an individual fluent in sign language for the hard of hearing will be advantageous.

- A procedure for controlling volunteers needs to be developed for the plan. Locations for them to report to, specific assignments, and identification procedures must be predetermined. Only the volunteer agency leader should be directed to go to the command post for an assignment.

A technique must be developed for recording where individuals are evacuated, for marking evacuated structures to prevent wasting time rechecking buildings, for maintaining up-to-date information on evacuees, and for redirecting families separated during the evacuation.

A public information procedure must be developed. It should include ways to release information, special telephone numbers for the media to get information, and special numbers for the public to call for information on the duration of the evacuation, location of

- relatives, and other items of concern. It is critical to provide accurate information to reduce rumors and the concern of the public.

- Specialized evacuation plans for penal institutions, schools, shopping centers and places of public assembly must also be developed.

Evacuation plan outline

Based on the preceding discussion of past incidents, problems encountered and suggestions for overcoming the problems, the following evacuation plan outline should be followed:

Title page Distribution list Change page Introduction

Need for the plan Agencies to implement plan Scope of plan Objectives that plan will meet

Agency responsibility Legal authority for implementing evacuation

Chain of command with backups listed

Evacuation of families of emergency response personnel

Emergency medical services plan for injuries during evacuation Childbirth Heart attacks Vehicle accidents Routine illnesses

Emergency medical services plan for evacuation of special facilities Hospitals Nursing homes

Evacuation plans for special facilities Penal institutions

Schools

Shopping centers Places of public assembly Air traffic Legal requirements Restriction of air space Ground traffic Route controls Check points

Tow vehicle availability—public and private

Communications with the public Language interpreters Hearing impaired Media input Media output Public input Training

Senior management reviews Practice in utilizing the plan

How plan can help

The EPA study best summarizes the need for an evacuation plan:9

- Based on the study of individual evacuations and consultation with persons having experience in managing and studying various aspects of evacuations, some general conclusions can be made.

- Advanced planning is essential to identify potential problems that may occur in an evacuation.

- The risk of injury or death to evacuees can be approximated by the National Highway Safety Council statistics for motor vehicle accidents, although subjective information suggests that the risks will be lower.

- Most evacuees utilize their own personal transportation during the evacuation.

- Most evacuees assume the responsibility of acquiring food and shelter for themselves.

- No panic or hysteria has been observed in evacuations.

References:

- Joseph M. Hans, Jr. and Thomas C. Sell, “Evacuation Risks—An Evaluation,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, (Las Vegas, Nev.), June 1974, p. 3.

- Ibid, p. 6.

- Ibid, p. 15.

- Ibid, p. 52.

- Mattie E. Treadwell, “Hurricane Carla,” DOD, Office of Civil Defense, (Denton, Texas), December 1961.

- Los Angeles Police Department, “History of the Los Angeles Earthquake, February 9, 1971,” (Los Angeles, Calif.), 1971.

- Jack Lowe, “Operation Green Light,” Oregon Civil Defense Agency, (Salem, Ore.) February 16, 1956.

- Joseph M. Hans, Jr. and Thomas C. Sell, “Evacuation Risks—An Evaluation,” United States Environmental Protection Agency, (Las Vegas, Nev.), June 1974, p. 42.

- Ibid, p. 54.