Planning Helps a Fire Department Cope With Chaos of Building Collapse

features

When a building collapses, the fire department gets the rescue call. It’s the kind of incident that severely tests a department with a variety of factors to be considered and organized.

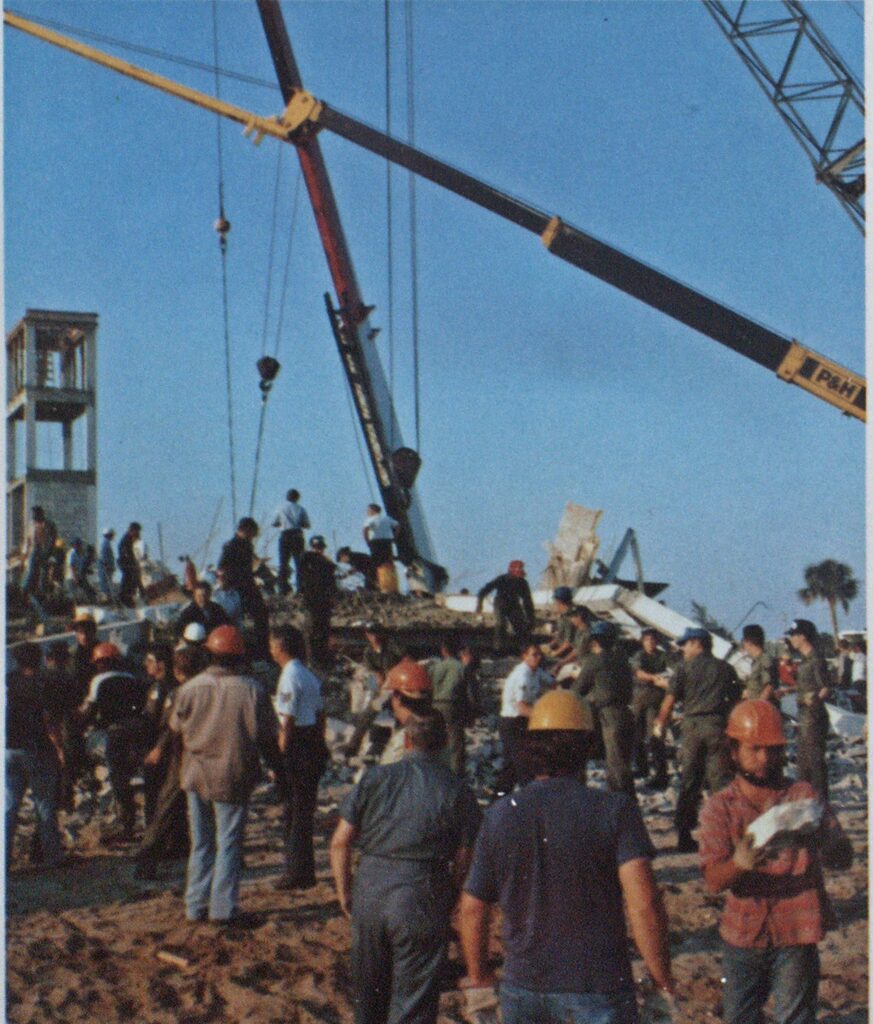

It could happen anywhere: in an existing modern structure, as with the recent Kansas City hotel walkway collapse; in a building under construction, as with the Cocoa Beach, Fla., incident described in this issue; or wherever there are tornadoes, earthquakes, explosions and fires.

The number of victims may be large but the exact number unknown. Some may be removed quickly with department equipment while others are trapped under massive structural elements, requiring specialized outside assistance. Suddenly hundreds of people may swarm to a collapse scene, making coordination especially important. Order must be brought out of chaos. Although easier said than done, the command post and critical communications must be established quickly.

The collapse may also involve fire, yet fire fighters cannot attack in the usual way because the rest of the area may be structurally unsafe.

Know authority

The absence of fire at a collapse scene introduces a possible legal question as well, according to Frank Brannigan, author of “Building Construction for the Fire Service.” While the fire department’s authority at a fire is usually clearly spelled out in the local law of every community, he reminds fire officers that “the authority to act or to direct others at emergencies other than fires is rarely defined.” That matter, of course, should be worked out before— not during—an incident involving collapse.

One item helps more than anything else to bring order to the potential chaos of a building collapse incident: a plan.

Most departments have an overall disaster plan, according to a survey by the International Association of Fire Chiefs for the Federal Emergency Management Agency. It is not just a* document for the fire department, but also for every other group that may become involved. Intermeshed with the overall disaster plan, however, is the department’s specific plan locating and removing victims of a collapse. The operation may take as long as several days, but the steps are the same.

- Survey the site.

- Immediate care and removal of surface victims.

- Searching for victims in voids and potential shelters in the debris.

- Removal of selected debris.

- General rubble removal.

Site survey

An initial size-up and survey of the site is similar to that of any major fire incident. The idea is to gain the information necessary for decisions on manpower, equipment required and techniques to be used. Any decision to call for outside equipment and personnel should be made as quickly as possible, with an understanding of the extra delay to be expected from crews not on standby and not trained in emergency response.

Although rescuers will want to begin operations as soon as possible, time must be taken during the site survey to consider safety requirements.

At a New York explosion and building collapse described in a recent issue of “WNYF” from which the five steps above were taken, one teetering wall was pulled down and another shored up before extensive operations could begin among the other debris. One fire fighter was assigned to continually watch the shored wall to report any shifting. Even when shored, an unstable wall could be affected by the vibrations of heavy equipment.

Photo by Bob Cross, Orlando, Fla., Fire Department.

Disrupted utilities

A building collapse almost always will result in ruptured electrical, gas, water and sewer lines. Although these items are normally the responsibility of utility companies, some situations may require action by rescue personnel. The disaster plan should instruct in the proper way to shut off utilities. Other hazards to trapped persons and fire department personnel may be gases used in refrigeration units and chemicals used in industrial operations.

Rescuers should assume that all downed electrical lines are “hot” unless known to be safe; energized wires do not Always spark or indicate being live. Pools of water close to live wires may be just as dangerous as the wires.

Problems with broken sewers are not as quickly recognized as the problems with electricity and gas. Dams may have to be improvised to keep any flow away from victims and rescuers. Furthermore, the sewer gases can be explosive as well as toxic. Self-contained breathing apparatus should be worn.

Surface victims

While the officer completes the site survey and requests any outside assistance, visible victims can be removed from the danger area and given immediate care. If the located victim is partially trapped, aid may involve uncovering faces and supplying oxygen until complete removal is possible.

When the surface victims are removed the most difficult work at looking under the debris for other more seriously trapped victims begins. Directions of bystanders are often unreliable. This was the case at the New York collapse, for example. Better information may come from survivors or injured victims who were closer to the action and may have been near others during the collapse or immediately afterward. Bystanders and survivors, however, may be disoriented by the stress of the situation.

In Cocoa Beach, no one had a reliable list of how many workers were on the scene before that collapse. Even if a so-called accurate list is available, there is the possibility of mistake, unknown visitors or unauthorized trespassers at the time of the collapse. Some victims may be taken to hospitals before the arrival of aid. In fact there may be no one trapped after all, but the working assumption must be that others might be somewhere under the debris.

Looking for voids

Although the Cocoa Beach incident was a pancake collapse—flat layers stacked on top of each other—many incidents will produce a jumble of debris. When floors fall unevenly, lean-to or v-shaped voids are produced where victims may have survived. But the jumble is predictably unstable, and personnel should be kept off piles as much as possible during a search.

Tunneling may be required to reach some voids. Construction of tunnels and the all-important bracing is usually the work of outside specialists rather than fire department personnel. Tunneling is said in the book “Emergency Care and Rescue” to be one of the hardest jobs in rescue work, and it should be undertaken only when other methods are impractical.

The collapsed building may have a cellar with a sidewalk entrance. Then rescuers can enter and reach victims in voids perhaps faster than digging from above or tunneling. At the New York collapse, rescuers entering the dangerous cellar used SCBA and had lifelines attached.

Calling and listening

Sometimes conscious victims hidden in voids can be found with a coordinated “round-the-clock” hailing system, in which rescuers are arranged in a circle around the building or part of it. One rescuer after another (round the clock) calls out and then listens for any victim who can respond.

Coordinating the quiet listening periods is very important, but difficult. The high noise level of responding sirens, nearby pumping engines and other equipment made this method impossible at the New York incident.

Recognizing a body in debris is another difficulty. To avoid further injury to a victim, tools should be used with great care. When close to a victim’s possible location, debris removal should be with gloved hands.

Selected debris removal

Selected debris removal, to continue the search after all voids are checked, requires the heavy equipment. In New York the fire department recognized the importance of planning for the coordination of all assisting agencies, yet the recent incident reminded that all plans are altered by actual conditions.

In Cocoa Beach Chief Bob Walker is expanding his resource list of available equipment because of the complexity of such disasters. Kansas City, which handled its recent collapse admirably, has a 39-page catalog of metropolitan emergency resources that is updated annually. Of course, heavy equipment phone numbers are not enough; companies and operators, as well as other official agencies, must be consulted when a plan is devised.

Compensation

Often overlooked when emergency phone numbers are compiled are the arrangements to compensate for the use of expensive outside equipment. Agreements must be reached on a local level.

In Kansas City, outside companies are required to assist during the first 24 hours of an emergency without guarantee of payment if “public facilities are unable to arrest further damage to humans or property values nor reestablish an orderly physical environment…” If a disaster situation continues, equipment and operators may be required for another 48 hours, but payment is provided “at cost.”

Many companies would be proud to be of assistance in an emergency and would not be concerned with payment, but this matter also should be discussed before an incident, not during.

Saying thanks

Regardless of any financial matters, fire department rescuers in Kansas City knew that they were grateful for the outside assistance so willingly provided. In a thoughtful gesture the department presented certificates of appreciation to those who participated from outside the department.

After selected debris has been removed and all likely voids checked for survivors, the odds for finding others alive decreases. Nevertheless, bodies must be found also. General rubble removal is then used when persons are still missing. This should not be confused with a general cleanup to clear a site for rebuilding. General rubble removal is a systematic part of the rescue operation and should be supervised accordingly. Miracle rescues can occur even when the situation seems hopeless.

New York Fire Department photo by Fireman A Guerriera, courtesy WNYF

Photo by David Handschuh, courtesy WNYF

Soon after any collapse incident is declared over, a critique of the entire operation is in order. If parts of the plan worked extremely well they should be noted. But not every incident can be handled according to an untested plan. Use the new information gained from experience, while its impact is still fresh, to reshape the plan for next time.