“Up, up, and away” is not a verse from a song; it is a rule in dealing with a hazardous materials spill that may save your life or the lives of your firefighters.

The hazardous materials environment is one into which firefighters should NOT go racing, sirens blaring; with hazmat, restraint is the order of the moment. When faced with a hazardous release, we must ask some vital questions before developing our incident action plan (IAP). What is it? How much is there? Is a rescue required? What is the evacuation profile? What are the risks vs. benefits of any action? And my personal favorite, What would happen if we did nothing except isolate and deny entry?

Once we have answered these central, vital questions, we can develop our IAP. Stay uphill, upwind, and away from the substance until you know what you’re dealing with.

What is It?

This first question is critical. Knowing what we are dealing with is vital to making good choices that will allow us to ensure mitigation of the incident while protecting our most important priority: our personnel returning to quarters safely.

- Three-Point Hazmat Size-Up

- Hazmat Survival Tips: Hazardous Materials Incident Size-Up

- The Process of Making Decisions At Hazardous Materials Incidents

Do you have an acid leaking into a storm drain, or is this a dairy truck leaking milk on a country road? There are a number of sources to identify the substance. Interview the responsible party such as the vehicle driver, plant supervisor, technician, and so on. If shipping papers can be located, these are very helpful. But where vehicles are concerned, these documents are kept inside the vehicle, making access difficult in a release. Placards, four-sided markings on transport vehicles, give us a clue as to material type, but they do not specifically identify the material. Placards can also be a bit misleading. For example, anhydrous ammonia is placarded green as a nonflammable gas, the same as oxygen. Anhydrous ammonia gas is one part nitrogen and three parts hydrogen. Under the right conditions, ammonia will burn and can explode violently! This happened at the fertilizer factory in West Texas in April 2013. The Oklahoma City bombing was propagated with fertilizer. The processes used to manufacture many fertilizers rely heavily on anhydrous ammonia. Consult multiple sources to develop your IAP.

It may be necessary to contact the shipper, so look for markings on the vehicle or container to identify the shipper. You may also need to have law enforcement back-trace the vehicle license number through your state department of motor vehicles to find the owner. Until you know what it is, you are making decisions based on speculation, and that’s a dangerous place to be. Make attempts to identify the material or the vehicle from a distance. The most important hazardous materials tool you can have on your fire unit is a good pair of binoculars.

How Much is There?

The answer to this question is not how much is spilled but the potential of the spill? What’s the size of the container? Is this a leaking 5,000-gallon tanker, a pipeline rupture, or a one-gallon bottle? The amount of the substance you will be dealing with is a central driver in developing your IAP. Hydrochloric acid (HCl) is a clear, colorless material that is highly corrosive. If you have an overturned tanker leaking this material near a populated area, your challenges for isolation, evacuation, and containment will be daunting. Then, you have rescue considerations. If you have a one-gallon container spilled in a parking lot, you can probably neutralize this amount with some potassium carbonate, commonly known as pot ash after first donning the appropriate self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) and personal protective clothing.

Is a Rescue Required?

The presence of victims or people down in a hazmat spill is NOT a reason to run into the immediate spill area with only our turnouts and SCBA. If the substance is powerful enough to knock people down and incapacitate them to the point where they cannot walk or crawl out on their own, you’re dealing with a seriously dangerous substance. Don’t become a victim; be a part of the solution, not a part of a bigger problem by becoming incapacitated yourself. I know there is a school of thought that we can run into the spill area wearing turnouts and SCBA, quickly grab the victims, and heroically drag them to safety. I strongly disagree with this notion. Read the label inside your turnout coat; it almost certainly says something like, “Protective ensemble for structural firefighting in accordance with NFPA [National Fire Protection Association] 1971-2007…” or “This garment meets the garment requirements of NFPA 1971, Standard on Protective Ensemble for Structural Firefighting, 2007 edition.” There’s nothing here that qualifies your turnouts for entry into a hazardous chemical environment outside the structural firefighting realm.

If you have victims in these environments that cannot self-extricate, you will need to enter the area wearing the appropriate chemical protective suit with full SCBA protection. This can only occur after you have established isolation zones, set up a full decontamination area, have a backup crew in place, and have confirmed your chemical suits are compatible with the material. We will address a full hazmat scene setup later in this article.

What is the Evacuation Profile?

With a large spill, the extent of your evacuation area is best determined by using one of the commercially available hazmat management programs. These computer programs can estimate threat zones associated with hazardous chemical releases including toxic gas clouds, fires, and explosions. Book sources, such as the Department of Transportation Guidebook, provide guidelines for evacuation but do not show map overlays of your area that outline the evacuation zone. A critical distinction to remember is that evacuation is made in areas where the chemical has the potential to spread but has not yet impacted that specific area. Rescue occurs for victims that need to be removed to safety and are already in the chemical release area. Evacuation is typically a law enforcement function, so give that one to police department.

When designing you evacuation parameters, follow the recommend actions for what you have. It may be tempting to think you should double the evacuation distances for an extra measure of “safety.” If trusted sources recommend being 100 feet upwind, 100 feet away on each side, and 200 feet downwind, follow that recommendation. Doubling those numbers doesn’t give you twice the area to evacuate; it quadruples the area! With a greatly increased evacuation zone, you may miss someone in the true threat area that should have been relocated while you’re busy evacuating people you don’t need to; this can create a liability. Stick to the facts, and don’t give yourself more headaches than are necessary.

You must take into account what problems a mass evacuation will create. Traffic jams or citizens simply running out of their homes can cause people to become exposed to the material from which you are trying to protect. Shelter-in-place may be the best direction you can give to the community, particularly if the leak is a gaseous release.

Richmond, California, in the San Francisco Bay area, has large chemical processing facilities in its jurisdiction. This community is well briefed on emergency procedures. Richmond maintains early warning sirens, and the community is instructed on procedures to follow for sheltering in place when warning sirens sound. They use a simple “shelter, shut, and listen” plan. Shelter in place; shut all windows, doors, fireplace flues, heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning; and listen to radio and television for instructions.

Richmond also maintains a Web page that shows the shelter-in-place procedures. If your community has chemical facilities nearby, the population should be well briefed on what to do during a release, i.e., evacuate vs. shelter-in-place. Many communities have a reverse 911 system. These systems allow emergency service providers to send a recorded message with instructions to telephones in a designated area. Reverse 911 systems typically only send the message to landline based phones. Monterey County in Central California has a system (alertmontereycounty.org) that allows citizens to preregister their cell phones to also receive alerts sent to their home phone number.

What is the Risk vs. Benefits of Any Action?

This question is one we should always ask regardless of the nature of the emergency with which we are dealing whether it is a house fire, a rescue, a crazy person on the street, and so on. In the case of a hazmat spill, we need to weigh and question what actions are truly necessary AND if we can undertake those actions while maintaining safety. Is there a serious threat to life? Are we simply trying to limit property damage? Do you have entry suits compatible with the released material? Can we assemble adequate resources? A hazardous materials incident in which we are making entry requires a full IAP and complete setup with proper entry suits, isolation zones, de-con, entry teams, monitoring, a briefing, and a command structure prior to that entry occurring; this is just a partial list. Setting up a full structure to deal with the incident will take at least 30 to 60 minutes, so patience in the face of difficult challenges is a must. Remember, we do not take risks; we minimize the hazards to a manageable level.

What Would Happen if We Did Nothing Except Isolate and Deny Entry?

This is the central question we need to ask at any hazardous materials release. My old friend and former hazmat instructor Dieter Heinz often referred to hazardous chemicals as “animals” that will “get us” if we let them. So the logic here is, “don’t let them get you.” If we can isolate the material, deny entry, build a containment dam a safe distance downhill, and evacuate the public from potential danger zones, this should be our approach. Or, should we simply isolate, deny entry, and retreat to a very safe distance? A private company with the knowledge, training, and equipment can be called by the shipper to clean up the mess.

If we have victims in the immediate spill area or our entry into the dangerous environment will play a critical role in protecting the public by preventing further release, then entry can be considered IF we have the resources available to make that entry. Making entry into the hazmat environment simply to prevent property loss—with no threat to life—is a decision that should bear very close scrutiny.

In any event, if we decide the risk vs. benefits allow us to consider entry, only make that move once we have a complete hazmat management scene in place.

The Hazmat Incident Management Scene

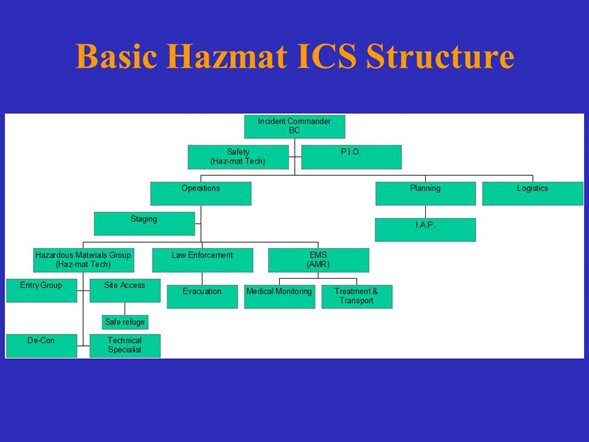

After answering the questions posed above, incident management starts with an IAP. The plan is a simple, written document that describes the incident objectives with appropriate attachments such as chemical descriptions, weather predictions, communications plan, material safety data sheets (MSDS), and so on. The minimum command positions to be staffed prior to entry are incident commander (IC), safety officer, hazmat group supervisor, entry team leader, decon group, site access control, staging, and public information officer (PIO).

I believe in having lots of resources on scene. Santa Clara County in the South San Francisco Bay area is the center of the high-tech Silicon Valley. The County has several fire departments with entry-level capable hazmat teams. In any significant hazmat release, multiple agencies are available to respond with trained personnel, equipment, and specialized vehicles. These departments train together regularly, hold meetings, and are familiar with each other’s capabilities such as different monitoring equipment. The severity of a hazmat incident, especially where you are making entry, requires anticipation of the situation magnifying in intensity. Stay ahead of the incident by getting plenty of personnel and equipment on scene early! All personnel in the support zone must have SCBA on with face piece ready to don.

A good way to keep the press from adversely affecting your incident scene is to give them something to report. Assure the PIO sets up a press section in a safe area away from the ICP from which reporters can transmit their video feeds with a view of the incident in the background; reporters love that. Use the press to notify the public of actions they should take such as shelter-in-place.

Prior to beginning operations, the IC must hold an incident briefing. This is best held at the entry point next to decon so the entry firefighters who are partially in their suits don’t have to try and move too far. The briefing must, at a minimum, have all the section and group leaders, but I prefer to have all personnel on scene present. The briefing should cover all the aspects and objectives of the IAP and EVERY section and group leader gets a hard copy. This is the time to answer questions (before you begin operations with personnel entering an atmosphere with a dangerous release). Make sure everyone understands the emergency retreat guidelines in the event the support zone becomes contaminated. The retreat plan should designate one location for everyone to assemble so all personnel can be accounted for. Constant monitoring of the support zone is essential to safety.

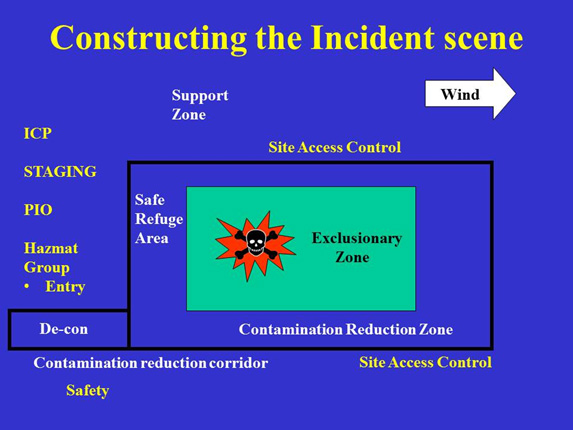

A full-scale hazmat operation using level “A” fully-encapsulated suits for entry requires filling many command and operational positions. The diagram below shows the minimum command structure and scene operational plan that must be used for any hazmat operation where personnel will don suits and enter the danger zones. The diagram is not necessarily to a particular scale; actual distances may be much greater ratios.

Selecting the appropriate hazmat entry suits requires careful consideration. Guesswork is NOT the way to do this. Appropriate chemical compatibility charts or other trusted sources must be used to ensure that the protective clothing used can be relied on to safeguard entry.

Level A fully-encapsulated suits with SCBA inside or a tether hose to provide air give a high level of protection, particularly with vapor clouds or an unknown substance. Exhaled air from the SCBA or—if used—the tether line, provide a positive pressure environment inside the suit. Level A is very cumbersome, has limited visibility, is hot and stressful to wear, and takes the most time to don and take off. Level A is best for unknown materials, skin absorption hazards, or where there is a vapor/gas inhalation hazard.

Level B suits are typically chemical suits with SCBA worn on the outside. Level B suits are appropriate for low-oxygen environments with a chemical splash hazard that has minimal chances of producing vapors. Level B is less cumbersome to wear than higher levels of protection and is less tiring to the wearer. Level B should only be considered when the name of the spilled material is confirmed and proper procedures allow use of level B.

Level C is typically a canister mask that has the appropriate filters and also has built-in eye protection. The mask is worn with appropriate protective clothing. With level C, confirm the type of material and in a powder form. There cannot be any compromised atmospheric conditions or low oxygen levels with level C use.

Level D represents your turnouts or station overalls. These garments provide NO designed chemical protection. Turnouts are appropriate for structural firefighting environments and can be appropriate for small hydrocarbon spills such as gasoline on the roadway at a vehicle accident where we use absorbent material to remove the hydrocarbon.

If the incident conditions present an unknown material that requires chemical testing and/or getting a sample to identify the contaminate, my commandment is to have the sample gathering team enter in level A, go through complete decon, and then proceed with the incident once the chemical testing identifies the material. Always remember that both liquids and powders can react violently with water. This is why paying attention to the climate conditions and attaching a weather report to the IAP is so important. You can have a relatively benign appearing powder or liquid spilled on the roadway, but once you get some rain falling, you suddenly have the material spreading, a possible violent reaction, off-gassing, and all manner of things “magnifying.”

REMEMBER, HAZMATS ARE ANIMALS THAT WILL GET US IF WE LET THEM! DON’T LET THEM GET YOU!!!

Incident Operations

Once your analysis and IAP are complete with hazmat scene entry system setup, and you have made the very carefully considered decision to send some of your “beloved guys” (thanks to Tom Brennan for that term) into an extremely hazardous environment, constant vigilance is required. Rapidly changing weather and situational conditions can dictate an “abort.” Everyone coming out of the contamination reduction zone MUST go through full decontamination. Atmospheric monitoring must be ongoing. Every person on scene must have a portable radio to monitor the overall tactical channel in case the support zone becomes contaminated. The entry team must have its own dedicated tactical radio channel with no one else on that frequency. Site access control must maintain strict procedures on who is authorized to be anywhere near your operation. Constantly reevaluate your plan to confirm you are following the best and most necessary path while reducing hazards to a manageable level.

NEVER BE WARY OF CHANGING YOUR MIND AND DECIDING TO CALL AN ABORT AND RETREAT EVERYONE TO A SAFE LOCATION!!!

Case Study: Many years ago, the Monterey (CA) Fire Department (MFD) had many fish packing plants in its town. The primary refrigerant used was ammonia. An accident with a forklift damaged some ammonia lines, causing a gaseous release that poured out of the building across a main thoroughfare. All the employees ran out of the building, many suffering from exposure to ammonia gas that affected their respiratory systems and skin. MFD arrived and began sending personnel into the building in old canvass turnouts and SCBA. The objective of the entry was to shut a main valve on the ammonia gas system. There was no rescue as the employees had already exited.

The ammonia gas instantly penetrated the turnouts, causing ammonia burns on firefighters’ skin. Nine personnel went to the hospital. We were unaware of the hazards of “common” ammonia. Had we never left the station, the outcome would have been better. Had we done nothing, the ammonia tanks would have eventually drained without any intervention. The situation got worse the moment we showed up and made entry into an environment from which we should have simply stayed away.

The moral of this story is obvious: Have good, sound, well thought-out, well-confirmed, and documented reasons for what you do, and ALWAYS ask yourself, “What would happen if we just isolated, denied entry, and stayed away from this stuff?” Call a private company and it clean up the mess. Make sure everyone goes home safe in the morning!

Incident Position Descriptions

Incident commander (IC). The IC’s role is to supervise development of the IAP and command its implementation. The incident command system form 202 works well for the written format. The IAP is a brief outline that describes the goals and actions for the incident and gets everyone on the same page. Consult technical specialists as necessary to provide specialized knowledge about the material. CHEMTREC can provide this. Attachments are included to complete the plan. Key elements are of the hazmat IAP includes the following:

- Identification of the spilled material(s).

- Evacuation and/or shelter-in-place boundaries.

- Type of protective suits to be worn by entry team, i.e., level A Dupont-Tychem.

- Establishment of guidelines for entry into the exclusionary, contamination reduction, and support zones.

- An approved diagram of the incident scene showing control (isolation) zones, decon, and contamination reduction corridor (entry lane into the spill area).

- A weather report. Use a source that gives complete hourly weather predictions, such as accuweather.com. Attach a copy of the hourly weather report to the IAP.

- A safety message.

- A communications plan. Entry team should have its own tactical radio channel.

Safety officer. This position has authority to stop and prevent any unsafe acts. The safety officer oversees all aspects of the incident to ensure activities meet practice standards in all areas of health and safety. He consults with the IC to formulate and approve the IAP. He also reports to the IC and does the following:

- Participates in the preparation and implementation of the site safety and control plan.

- Ensures all safety measures called for in the IAP are implemented.

- Reports and intercedes on deviations of safety and control plans.

- Alters, suspends, or terminates any unsafe activities.

- Ensures emergency medical services (EMS) monitoring and examination of all entry team personnel.

Hazardous materials group supervisor. He is responsible for implementing the actions dictated in the IAP that pertain to the hazardous materials group and directs that group’s overall operations. He reports to the IC or operations if operations are activated and does the following:

- Ensures establishment of the control zones and access points. Directs containment measures called for in the IAP.

- Evaluates and recommends public protection actions and evacuation vs. shelter-in-place to appropriate agencies such as law enforcement.

- Establishes environmental monitoring.

- Conducts safety meetings.

- Ensures site safety and control plans are implemented.

Entry group leader. This position is responsible for the overall entry and exit operations of personnel into the spill/release areas. The entry group leader reports to hazmat group supervisor and does the following:

- Supervises entry operations.

- Ensures entry AND backup teams in place prior to danger zone entry.

- Recommends mitigation actions to contain the spills.

- Maintains communications with the technical specialist, decon group, site access control, and safe refuge area managers.

- Maintains close communications with the entry team on a dedicated tactical radio frequency.

- Carries out IAP actions regarding rescue, mitigation, release, or potential release.

- Maintains control of persons and equipment going in/out of the exclusionary zone.

Decontamination leader. This position provides overall management of decontamination activities as required by the IAP as well as the following:

- Identifies contamination reduction corridor.

- Ensures decon personnel are in protective clothing one level below entry personnel.

- Supervises decontamination procedures.

- Manages movement of personnel and equipment within the contamination reduction zone.

- Maintains communications with entry team(s) through separate, dedicated tactical radio channel.

- Coordinates transfer of victims to EMS after they are decontaminated to safe levels.

- Coordinate handling, storage, and transfer of contaminants.

Site access control leader. This position controls and ensures the safe movement and transfer of personnel and materials through the contamination reduction corridor. Site access keeps unauthorized persons out of the incident activity areas and does the following:

- Organizes and manages personnel assigned to control access to incident areas.

- Oversees the establishment of the exclusionary and reduction zones.

- Establishes a safe refuge area with the contamination reduction zone.

- Coordinates with EMS regarding potential victims.

- Maintains observations of changes in climactic conditions or other circumstances external to the hazard site.

Demetrius A. Kastros is a 42-year fire service veteran and a semiretired shift battalion chief from the Milpitas (CA) Fire Department. In 1974, he was among the first group of firefighters in the State of California to be certified as an emergency medical Technician (EMT). Kastros has a college degree in fire science and is a state certified chief officer and master instructor. He continues to work in fire service-related activities. He is the lead instructor for the City of Monterey (CA) Community Emergency Response Team program. He has been published previously in digital editions of Fire Engineering.