Haz-mat Rescue Team Decision Guidelines

HAZARDOUS MATERIALS

The natural and man-made release of hazardous materials into the atmosphere has been a concern of mankind for centuries.

Toxic sulfur-ladened gases, hot airborne ashes, and molten rock from volcanoes are all natural releases of hazardous materials. Methane—an asphyxiating and highly flammable gas—and radon—a radioactive gas—are naturally released from coal and uranium deposits.

In addition, there was undoubtedly carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide contained in prehistoric cave dwellings.

Today, society is more concerned with hazardous material releases from man-made industrial and technological sources. Because there tends to be a dense population near these activities, more and more people are at risk.

Concern for these releases has promoted the formation of emergency response teams to intervene in these incidents. The purpose of these teams is to prevent further harm to the people and the environment by the release and decontamination of the release site.

Some teams do not have the capability to conduct site decontamination. Their sole purpose is to rescue trapped victims, when possible, and to prevent further property and environmental damage through release containment or stabilization, if feasible.

Site decontamination generally occurs after the release is complete or has been contained. Decontamination teams sometimes perform containment, but it is not their primary function.

Although time may be of the essence in their subsequent actions, decontamination teams will not be confronted with the emotional, time-crunching decisions related to rescue and possibly release containment. In addition, decontamination teams do not have to decide if they should proceed, but how they should proceed.

A hazardous material release response rescue team (rescue team) must constantly decide whether they can carry out their tasks while maintaining personal safety and whether their efforts will result in a significant public benefit.

Each hazardous material release incident will create its own unique conditions and potential dangers to the public. The rescue team must consider all of these aspects when deciding whether or not they should risk intervention. Some factors that influence this decision are: the uniqueness of weather conditions, a collective efficiency of team experience, an improvement in equipment, site accessibility, or a difference in response time.

Remember, as long as conditions are stable, the hazard(s) associated with a specific material will remain the same. A corrosive material will be corrosive whether it is in a laboratory beaker or in a corrosion resistant tank truck. However, if a person is not exposed to this material, he is not at risk.

A person who is carrying the beaker or an automobile driver on a collision course with the tank truck are both at high risk to the hazard. A person in the next lab or an automobile driver in the next county are at no risk to the hazard. The hazard, however, remains the same; it is a corrosive material.

EFFECTS OF HAZARDOUS MATERIAL RELEASE

The release of a hazardous material may have an adverse effect on people, property, and the environment in general. Obviously, anyone in the vicinity of the release may be in danger, depending on the hazard(s) associated with the material.

Also keep in mind that each person or group of persons may have a different level of danger (risk) upon their exposure to the release. The occupants of a nearby hospital or nursing home would have a potentially greater risk compared to the inhabitants of an adjacent high-rise apartment building. The hospital or nursing home patients would tend to be less mobile than the average apartment dwellers during an evacuation. Their general state of weak health would also tend to increase their susceptibility to airborne toxic materials.

The apartment dwellers may be at a greater risk than those people living in a suburban housing development because the population of a suburban housing development will be less dense. In addition, evacuation time could be lengthened by the slow elevator response in a tall building. Evacuation in both instances would depend on how quickly each occupant was notified to leave the premises.

Hospitals, nursing homes, and, possibly, high-rise apartment buildings will have evacuation plans, but suburban housing developments may not.

Property at risk also may have dramatically different risk levels. Compare a local government office building that contains all of the city’s official records with an abandoned warehouse; or a dairy barn that houses a prize herd of cattle with a construction-site tool shed.

A final example is to compare a playground with an amusement park. There will probably be little if any loss in revenue from a contaminated playground, but there could be a devastating loss for an idled amusement park at the height of the season.

The potential for environmental danger may be the most difficult to assess when you must make an “on-the-spot” decision of whether or not to intervene in a hazardous material release incident. The potential dangers involved with a hardwood forest at risk may be relatively easy to assess compared to the hazards involved with a pasture field. It may be harder to decide if you should intervene in an incident at a newly planted windbreak along a fish-stocked, “borrow pit” pond that is adjacent to a new interstate because of the potential risk to the surrounding community.

INTERVENTION VS. INACTION

Intervention by a rescue team could possibly worsen the effects of a release, but it cannot immediately reverse the conditions to their normal state prior to the release. Even with the appropriate equipment and training, the best that the rescue team can do is to prevent further spread of the effects of the release.

Rescuing a person who is beyond the point of resuscitation will not improve the situation. Extricating an exposed person will prevent further exposure and perhaps save the person’s life, but it does not change the fact that the person was exposed.

One thing vou must evaluate and try to project, is what the after effects will be if a release is allowed to continue to completion, or if it is halted, slowed, or perhaps even purposely accelerated in special cases. We have tried to bring some order to these assessments by assigning arbitrary values to risk levels assumed by a rescue team if thev elect to intervene in the release, and to the public consequences of the team’s inaction if they decide against intervention.

Consequences of either decision may be considered negative depending on circumstances surrounding each specific incident.

EVALUATING RISK LEVELS

When considering the risk levels, we must take into account that both the team and its equipment would be at risk. A budgetstrapped team would be forced to carefully evaluate the public benefit of intervention in a situation where no lives or injuries to people would be at stake, but where there was a high risk of damage to hard-to-replace equipment. A rescue team without proper equipment is just as ineffective as one without members.

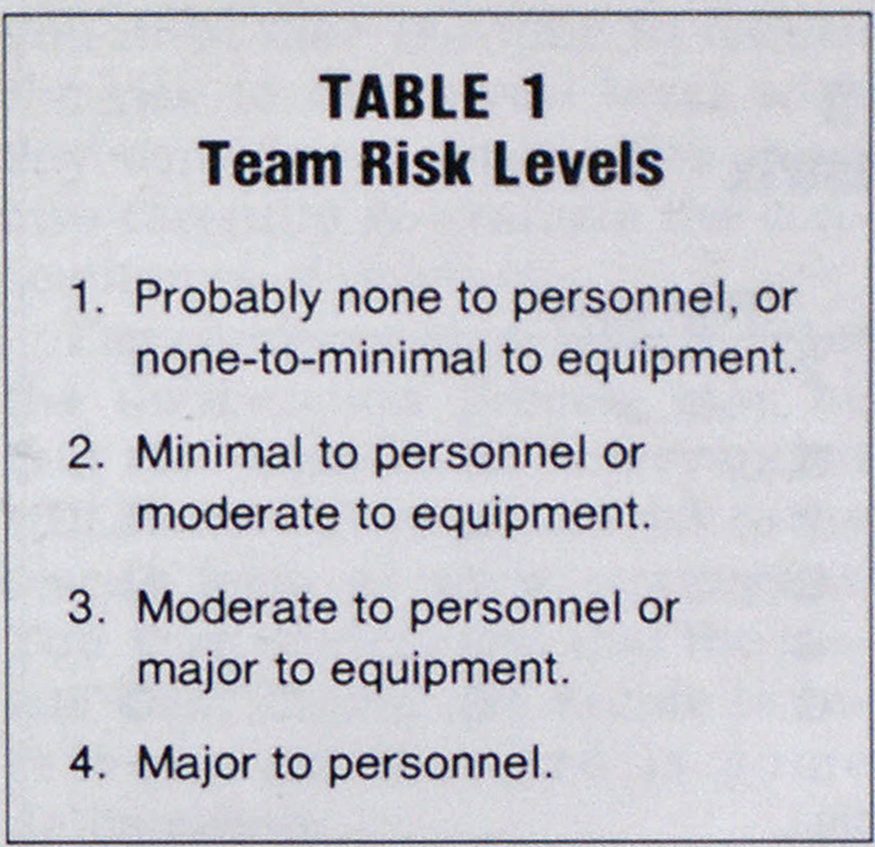

Table 1 above shows four arbitrary levels of risk to team personnel or to their equipment. You should note that the term “personnel” includes not only the rescue team, but anyone who is assisting them. For example, all personnel manning a hose to “knock down” released vapors should be included in the risk evaluation and so should their equipment.

It is not necessary to combine the risks to personnel and to equipment in order to determine the risk level. However, it is difficult to imagine any instance where personnel would be at a high level of risk unless their equipment, especially personal protective equipment, was at the same or higher level of risk.

According to Table 1, a minimal risk to personnel means that one or more members may experience some injury or health effect that would require first aid treatment and perhaps a short-term recuperation. Minimal risk to equipment means that any damage could be repaired on the spot, at least temporarily, for continued use.

Moderate risk to personnel denotes that one or more team members might experience some injury or health effect that would force them to withdraw from action and seek medical attention beyond first aid. Moderate risk to equipment means that any damage is probably repairable, but not at the scene, and the equipment is not usable until it is repaired.

A major risk to personnel means that a life-threatening injury or health effect is possible. A major risk to equipment indicates that replacement will be necessary or that any repairs would approach the cost of replacement.

The divisions within Table 2 on page 31 are equally arbitrary. The table depicts five different types of instances that could occur at an incident and the probable effects of inaction, should the rescue team decide that is the course to take.

Serious injury to people (other than rescue team personnel) means that their condition would require hospitalization and involve a significant recuperation time.

Minor property damage indicates that the property is in a readily repairable condition. For example, it is not necessary for tenants to live elsewhere while the roof of their house is being repaired.

Moderate proprty damage denotes that although the property is repairable it cannot be useful until it is repaired. For example, a saddle horse may have to be allowed time for its chemical burns to heal before anyone can ride it again; or the milk from a dairy herd must be dumped until the animals’ bodies are totally free of the inhaled vapors. A building may have to be decontaminated before it can be re-occupied.

Major property damage means that replacement is necessary because repairing the property would cost almost as much as replacing it.

Minor environmental damage refers to an obvious change that may become apparent in the natural surroundings, but that could correct itself with time. An example of this is singed leaves on one side of a tree.

Moderate environmental damage means that man may have to assist the natural forces in correcting the effects of the incident. This could be a 500-gallon oil spill that enters a storm water sewer. As a result, it might be necessary to excavate and sod a damaged lawn so it could be replaced.

Major environmental damage means that there could be longterm effects that may require a significant effort to correct. Examples of major environmental damage are the sterilization of a lake or the destruction of a hillside forest.

Table 3 opposite is a matrix that matches each set of circumstances in Table 2 with one of three decision possibilities:

- (G) = immediately intervene in the incident in some manner in order to frustrate the continuation or spread of the effects of a relase;

- (?)=obtain more information during deliberation before adopting some action;

- (N)=do nothing, at least for that moment, and re-evaluate.

Deliberation before action may involve merely reviewing the identification of the material and its associated hazards. You may have to take the time to select the safest route to and from the site, or to quickly rehearse the team members’ roles. During deliberation you must take the time to reduce the risk to the lowest level with any considered action. You must also carefully re-evaluate the consequences of inaction.

The decision that results from the deliberation process may be that the benefits of intervention still do not outweigh the risk to the rescue team or their equipment. You must understand that the rescue team should not decide to intervene until there is some deliberation.

Note the outlined situations on pages 32 and 33 that involve hazmat releases and our application of the matrix to reach our recommendations. Try your hand at fitting the situations into the matrix or make up your own situations.

SUMMARY

You can find examples of similar matrices in literature on product safety, systems safety, job hazard analyses, and, more recently, in risk/benefit analyses involving public health issues. It’s a good idea to adopt other risk levels, to rearrange or expand the inaction effects, and to construct a personal matrix.

However, keep in mind that such tables and matrices are most valuable only during planning and training exercises because it is doubtful that anyone would take the time to consult them during an actual decision-making incident.

There is a simple form you can design that would allow an on-thescene observer to insert the risk and benefits assessments into his matrix. The basic question that each team will collectively ask and answer is: “What might happen to us if we do, and what might happen if we don’t?”

The bottom line is that the team must decide that the risks they are willing to assume are outweighed by their capability to intervene and the overall benefit to the community. A rescue team would cause the greatest harm by underassessing their risk, over-assessing their capability to intervene, and over-assessing the potential benefit to the community.

The more training and experience that a rescue team has under its belt, the more likely that correct evaluations will be made during an incident. Training is the major element in reducing personal risks because it allows a team the opportunity to gauge their capabilities and provides the opporunity to gain experience.