By Jack Sullivan

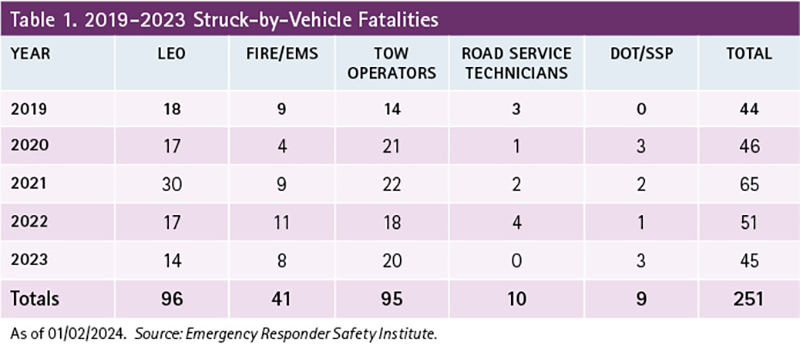

This year marks the 25th year that I have been working on preventing emergency responders, including firefighters and EMS personnel, from being struck by vehicles while working at roadway incidents. A lot has changed related to this hazard, including more use of blocking at incident scenes, high-visibility graphics on apparatus, better training available about working roadway incidents, and even better collaboration between all agencies working those incidents in most places. And yet, we still see far too many emergency personnel struck and killed or injured at roadway incidents. The number of emergency vehicles struck with warning lights flashing, reflective graphics, and temporary traffic controls in place is staggering. The statistics don’t seem to reflect the effort that goes into setting up safe operations at roadway incidents.

- Strategies and Tactics for Roadway Incidents

- Roadway Incident Operations and Safety: A 20-Year Review and a Plan for the Next 10 Years

- Highway Incident Safety: The Hits Keep Coming!

- Safe Interstate Highway Response

Then again, as I scroll through social media posts and news stories with photos and videos of roadway incident scenes, I see indications that it’s a good time to review the fundamentals for roadway operations. Are we doing everything we can to protect our personnel and the motoring public at every roadway incident? Let’s review some of the fundamentals.

Training

The most recent edition of National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety, Health, and Wellness Programs, includes a requirement for every fire department to provide training on roadway hazards and safety for all personnel (NFPA 1500-2021 Chapter 9). In many places, basic firefighter and EMT training does not include roadway hazards, so the individual fire departments and EMS agencies are responsible for providing that training. The National Traffic Incident Management training program (ops.fhwa.dot.gov/tim/training/), available for free in every state as an in-person or online class, is a good starting point. The program covers the very basic actions to be implemented at every roadway incident.

If your response area includes challenging roadways like bridges or overpasses; tunnels; or multilane, high-speed, limited-access highways, then there are other training topics you should cover, and all agencies are encouraged to include roadway operations in their annual in-service training rotation. That annual refresher training should review your department’s standard operating procedures (SOPs) for roadway operations.

Free Roadway Safety Teaching Topic Packages are available (respondersafety.com/training/roadway-safety-teaching-topic-packages-for-instructors/) for company officers looking to pull together company level drills on specific subjects. Additionally, free Online Training Modules about all aspects of roadway incident operations are available to all on the Responder Safety Learning Network at learning.respondersafety.com/Training_Programs/.

SOPs

NFPA 1500 also requires each fire department to establish, implement, and enforce SOPs regarding emergency operations involving traffic. The standard also provides guidance on the type of operations and activities that should be included in the SOPs. When developing an SOP for your department, consult local law enforcement and Department of Transportation (DOT) personnel so the SOPs are in line with state, regional, and local laws, guidelines, and protocols. SOP resources can be found here: respondersafety.com/resources/sop-s-sog-s/.

Include your call takers and dispatchers in the process, and make sure they understand the important role they play in obtaining location and conditions information and dispatching the appropriate apparatus, personnel, and support services like safety service patrols and law enforcement. In many areas, it is appropriate for the fire department dispatch center to notify the regional Traffic Operations Center (TOC) or Traffic Management Center (TMC) about an incident so that they can initiate steps to notify traffic in the area through 511 services, variable message signs (VMS), and media resources.

Make sure new personnel are trained in roadway operations before they respond to their first emergency run. It’s imperative that new personnel understand the hazards of working around traffic at incident scenes and that they know and follow the fire department SOP. Company officers need to keep roadway incident procedures in mind as they arrive at the scene of a traffic incident and provide important observations in their on-scene and windshield size-up report.

Communication, Coordination, and Cooperation

Among responding agencies, communication, coordination, and cooperation are critical for successful roadway incident operations. Communication should start long before the tones drop for an emergency response. Fire department personnel should be in contact with key personnel in other emergency response agencies on a regular basis.

Many regions use Traffic Incident Management (TIM) committees to facilitate the exchange of incident response protocols and problem areas. Most importantly, they serve as a forum to work through any issues as they develop so that roadway incidents are handled smoothly with all responders cooperating and collaborating on scene.

Check with your local DOT and state police agencies to get involved with a regional TIM committee or work with them to establish a regional committee if there isn’t one already in place in your area. More information about TIM committees can be found here: respondersafety.com/about-us/editorial-column/2022/11/why-we-need-tim-committees-now-more-than-ever/.

TIM Areas (TIMAs)

Just arriving at a traffic incident scene with an emergency vehicle and flashing warning lights is not enough to manage traffic or establish scene safety. The first arriving emergency vehicle plays a critical role in setting the scene for the duration of the incident. The initial incident commander needs to not only size up the observed conditions on arrival but also think ahead to visualize where other emergency vehicles will position, how traffic will operate around the incident scene, what other resources might be needed, and how emergency operations will impact traffic upstream of the incident scene.

Make every effort to keep all emergency vehicles on one side of the road, preferably the same side as the vehicles involved in the incident. Large fire apparatus should establish a “block” to protect the incident scene. Position the engine or truck at an angle to indicate to approaching traffic that your rig is stopped, parked, and not moving. Vehicles approaching at high speed can more easily detect when an emergency vehicle is stopped when it is parked at an angle instead of in line with traffic. Lane plus one (Lane+1) blocking is appropriate in the early stages of an incident; the block can be adjusted as appropriate as better temporary traffic controls are established. The officer in charge should provide specific positioning information for other incoming emergency vehicles—instructions like “Engine 3: On arrival, I need you to block right, in lane 3 and the right shoulder, upstream of Engine 1, and send your personnel to assist with extrication,” or, “Medic 4: Position downstream of the incident on the right shoulder.”

Four Strategies for Protecting the Scene

Four strategies can more evenly distribute the responsibility and associated costs of protecting road and highway incident scenes nationwide, across all responding agencies.

Purpose-built traffic management vehicles. Specialty vehicles that are designed to warn oncoming motorists and protect incident work areas are needed for quick response to road and highway incidents. Fire departments should not be expected to pay for or staff these specialty vehicles, although numerous examples of fire department traffic control vehicles exist around the country. The overall costs should be shared by all response agencies.

Fire departments need other traffic incident management team members including law enforcement, transportation, and public works agencies to step up and assist by providing staffing and responding emergency traffic control vehicles specially designed to manage traffic and protect highway incident scenes. The alternative would be to collaborate and coordinate financial resources for fire departments to design, acquire, equip, train, staff, and respond specialty purpose-built traffic control vehicles for emergency response to highway incidents nationwide. Most fire departments would prefer to have any other agency respond in a timely manner to provide temporary traffic control at roadway incidents with properly designed, equipped, and staffed traffic control vehicles to protect the incident scene, the victims, the emergency personnel, and the very expensive specialty fire and rescue apparatus and other emergency vehicles (police cars, ambulances, tow trucks) working the incident.

Cooperative agreements and action that truly shares the traffic control responsibility. Traffic control responsibilities need to be shared by responding agencies. Each community must develop a plan for doing this with all response agencies participating. We can achieve this collaboration through TIM committees that have proven to be effective in many areas. If other agencies cannot provide traffic control services in a timely manner at incident scenes, then fire departments should collaborate with transportation, public works, law enforcement, and other local agencies to fund and acquire purpose-built traffic control vehicles. Right now, some fire departments are taking on that responsibility and cost by themselves without support from any other agencies. It should be a team effort.

Funding. The cost of using fire apparatus as blocking vehicles at incident scenes severely impacts fire departments financially and in service capabilities. Fire and EMS departments are footing the bill and providing the service using volunteer personnel in many areas, while other agencies simply say, “We don’t have the funding,” or “We don’t have the necessary staff.” Can you imagine the chaos that would ensue if fire departments used the same excuses?

Digital alerting. The most common causes of these struck-by-vehicle incidents is that “D Drivers” are not looking out the windshield to see emergency vehicles and flashing lights as they travel down the road at highway speeds. Drivers involved in secondary crashes involving emergency vehicles and personnel sometimes tell us that they didn’t see the temporary traffic controls or emergency vehicles with flashing lights. We need a new tool or approach to get drivers’ attention. Digital alerting technology with audible in-vehicle warnings is different. Drivers don’t have to be looking at a screen or even out of the windshield to get an audible alert when it’s available. Equipping emergency vehicles with the necessary transponders and requiring all new vehicles to have the capability to receive digital alerts is another way to get critical advance warning to distracted, drunk, drowsy, and disgruntled drivers.

Is this a “move it” incident or a “work it” incident? In other words, can the vehicles involved be moved out of the flow of traffic to a side street, exit ramp, shoulder area, or parking lot, or does the crew need to begin operations on the scene as found on arrival? Does traffic need to be stopped, or is there a way to channel traffic around the incident scene? If you decide to block the roadway completely, be sure to notify the appropriate agencies of the closure and take steps to protect the back of the traffic queue that will develop. Are the personnel and resources needed to warn of the backlog or to set up temporary traffic controls on scene, or should other assistance be requested?

Make every effort to provide advance warning of the incident scene through the use of emergency vehicles (like safety service patrols or fire police), signs, traffic cones, flares, and digital alerts sent to navigation systems. Digital alerting systems can notify drivers approaching an incident scene or backlog audibly of the situation ahead through navigation apps and some vehicle infotainment systems. Those audible alerts may get the attention of drivers who are distracted by other activity at the time. “D” drivers (i.e., drunk, drowsy, distracted, drugged) are still some of the most frequent contributing factors to struck-by-vehicle incidents involving emergency responders.

Fire Apparatus and Ambulance Equipment

We depend on emergency warning lights and high-visibility graphics to help identify our units when responding to an emergency scene and when we are parked and operating at an incident scene. Fluorescent and reflective graphics help our vehicles to stand out in daylight and nighttime conditions.

Follow NFPA 1900, Standard for Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting Vehicles, Automotive Fire Apparatus, Wildland Fire Apparatus, and Automotive Ambulances (2024), for recommendations for emergency warning lights and apparatus graphics. Strive to keep apparatus clean and in good repair with all systems working properly. If your vehicles are equipped with digital alerting technology, be sure to enable that equipment so it will automatically send alerts when emergency lights are activated.

New LED warning lights produce much brighter flashes and more saturated colors than older lighting technology. Some of the newest LED systems produce flashing lights that are sometimes too bright in low light and nighttime conditions and contribute to drivers’ inability to see personnel operating around emergency vehicles. Consider dimming some lighting when parked at night so that your vehicle is still visible to oncoming traffic but not displaying scene or warning lights that contribute to glare for approaching drivers.

Some fire departments have been successful at installing traffic arrows and message boards on fire apparatus (photo 1). Other fire departments are deploying purpose-built blocking and traffic control units. And, while it’s uncommon, some fire departments have successfully collaborated with their state DOT to absorb some of the cost of building and operating traffic control vehicles. If you do not have DOT Safety Service Patrols operating in your area, consider requesting that type of resource through a regional TIM committee, state DOT, or state legislature. If the state DOT can’t deploy that kind of resource, consider requesting financial assistance to design, build, and deploy a fire department-based unit to provide that service.

(1) Photo by Inver Grove Heights (MN) Fire and Rescue.

Ensure your emergency vehicles are equipped with a minimum of five 28- to 36-inch-high orange traffic cones with reflective stripes. Teach your personnel the proper way to deploy these cones and chemical or electronic flares as appropriate. Cones and flares will serve to get drivers’ attention before drivers strike blocking apparatus. Adding warning signs upstream of the incident will also help get drivers’ attention ahead of time.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

Wearing high-visibility PPE was one of the first recommendations we made back in 1998 when we first started to address roadway incident operations. High-visibility garments that are compliant with the American National Standards Institute American National Standard for High-Visibility Safety Apparel (ANSI 107) should be available to your personnel. Anytime your personnel are operating around moving traffic, they should wear high-visibility garments of some kind, like a vest, jacket, or coat. For firefighters exposed to fire, flame, heat, or hazardous materials, there is an exception and NFPA-compliant turnout gear is acceptable. Very few high-visibility garments are designed for proximity firefighting operations. Try to pick PPE color combinations that are in contrast to the general color of your emergency vehicles. If the color of your PPE is similar to your vehicles, then your personnel will not be as visible. Photo 2 is an example of how similar colors can camouflage your personnel.

(2) Photo by Mike Legeros.

In the past few years, efforts have begun to improve head protection for personnel who are working at roadway incidents and are in danger of being struck by a vehicle. Traditional fire helmets do not provide adequate protection for lateral (side) impacts that would most likely occur. ASTM International, founded as the American Society for Testing and Materials, has been working on developing a new standard—ASTM WK82362, Pedestrian Roadway Worker Helmets. When finalized, this standard will specify performance requirements and test methods for protective headgear that individuals could wear who work on roadways, including public safety personnel in the fire service, emergency medical services, law enforcement, and other disciplines who routinely respond to roadway incidents. The standard addresses performance in terms of impact protection, positional stability, retention system strength, and field of view. When finalized and published, it will provide a standard for helmet manufacturers to design headwear more appropriate than the traditional fire helmet for roadway incident hazards. More information about helmets and head protection can be found here: respondersafety.com/training/helmets-and-head-protection/.

History has demonstrated that no matter what we do to protect firefighters, EMTs, fire apparatus, and incident victims at roadway incidents, “D” drivers will still find ways to disregard all warnings and visual indicators and drive into our incident scenes, striking emergency vehicles and personnel. The “me first” attitude of today’s drivers puts us in danger every time we respond to a roadway incident. Every time you step out of your emergency vehicle at a roadway incident, you are stepping into harm’s way. No matter how routine an incident seems, you should always follow your department’s SOP. This will allow you to provide your crew with the best level of protection. This is a good time to review the fundamentals of your department’s response procedures to roadway incidents.

Jack Sullivan is the director of training for the Emergency Responder Safety Institute, a committee of the Cumberland Valley Volunteer Firefighter’s Association (respondersafety.com). He is a subject matter expert on roadway incident operations and emergency personnel safety and promotes proactive strategies and tactics for protecting emergency workers from being struck by vehicles. He was a volunteer firefighter and chief officer for 23 years and in 2018 retired from a 40-year career as a safety and risk management consultant for the public and private sectors.