by Brady Robinette and Lan Ventura

In 2019 there were 33,244 fatalities and 1,916,000 injuries as a result of 6,756,000 motor vehicle collisions (MVCs) in the United States.1 This averages to almost four deaths every hour of every day. These staggering statistics contribute to the substantial risk emergency responders experience every day. Not only are emergency responders at an increased risk when responding to and returning from calls, they are at an even greater risk once on scene and outside of their vehicles. According to the Emergency Responder Safety Institute (ERSI) statistics, 2021 was the deadliest year for emergency responder struck-by-vehicle incidents. A total of 65 brave emergency responders lost their lives due to these struck-by incidents.2

The National Fire Protection Agency (NFPA) defines community risk reduction (CRR) as the process for identifying and prioritizing local risks, followed by the integration and strategic investment of resources to reduce their occurrence and impacts. In 2019 there were 3,5153 fire related deaths in the United States (US). MVCs claimed 9.5 times as many lives as fire deaths. Should the fire service be doing something to help address the issue of MVC related deaths? If we reflect on the definition of CRR, it stands to reason that we should. Not only does vehicular trauma pose a significant threat to the citizens we are sworn to protect, but it also poses a significant threat to the fire service and other emergency responders, who respond to an estimated 18,000 roadway incidents daily.

Some could argue that reducing the number of MVCs isn’t in the fire service’s wheelhouse and therefore it should be left to other organizations and agencies to address. This mindset wouldn’t be doing our citizens or ourselves due service. Others could argue that reducing the number of MVCs is too complex of an issue. I believe the perceived complexity of this issue has contributed to its failure to be resolved. When faced with a difficult problem, it is sometimes helpful to reflect on past examples to model a meaningful framework for a solution. In the early 1970s, a diversified group of 20 commissioners (Photo 1) spent two years developing a total of 90 recommendations to reduce deaths, injuries, and property losses from fire by 50 percent in the next generation.4 The results of their findings culminated into the iconic America Burning report. Can you imagine how insurmountably large this task must have seemed at the time? How could fires be prevented from ever starting, and in the event a fire does happen, how would they be made less fatal? These commissioners and all the other contributors involved before, during, and after the report didn’t let the enormous challenge deter them. If you’ve never read America Burning or it has been a while since you read it, I urge you to give it a read. The parallels between the fire problem back then and the vehicular trauma issues today are more similar than you might think. In the years after the report came out, significant progress was made in reducing the number of structure fires and related fatalities.

The America Burning report referenced public indifference to the fire problem in the nation. I see a public indifference to the vehicular trauma problem in America. We see it all too frequently in the news. Even the best and safest of drivers can be affected by this, as they can’t possibly control the actions of other drivers behind the wheel of a several-thousand-pound, high-speed vehicle. How many children’s lives have been cut short before they had a chance to grow up and change the world? How many families never returned from a quick trip to get ice cream? How many children will never see their dad or mom again as they commute home from work? We need the public to be outraged by this issue and demanding change.

To follow the successful model of the America Burning initiative, a diverse group of individuals is needed to collaborate and create an in-depth report of the current status of MVCs and their related injuries and fatalities in the United States as well as effective and meaningful solutions for reduction and prevention. Recommendations for reduction and prevention would be established from current research, educational programs, and case studies. It is important that these recommendations call for action from the local, state, and federal agencies and organizations.

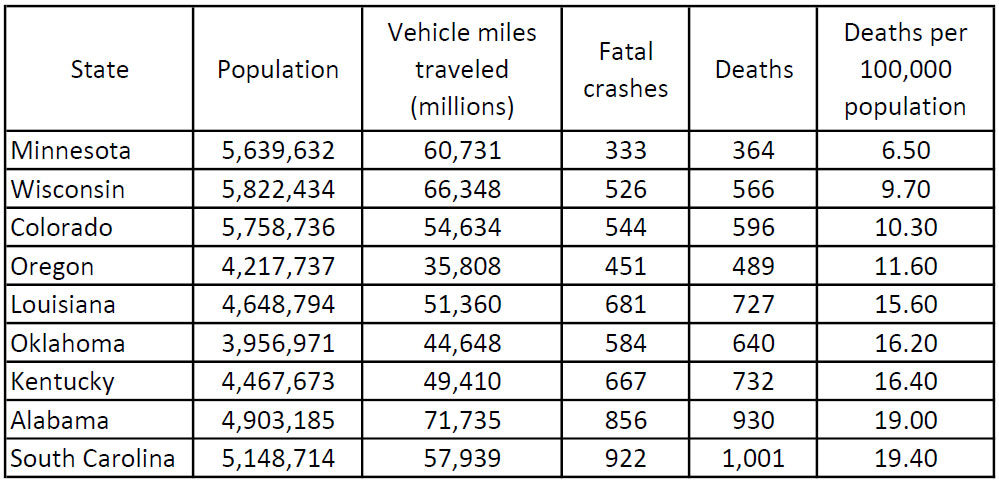

The primary focus should be centered around preventing MVCs with a secondary goal of injury and fatality reduction in the event a MVC does occur. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. crash death rate was more than twice the average of other high-income countries in 2013.5 The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) “Fatality Facts 2019 State by State” report shows large disparities in fatality rates per 100,000 population amongst states. Amongst nine similarly sized states based on population, Minnesota’s deaths per 100,000 population is 6.5 while South Carolina’s is 19.4 (Table 1). Overall, the District of Columbia is the lowest at 3.3 and Wyoming is the highest at 25.4.6 More research as to the cause of these disparities as well as any actions taken as a result are necessary for formulating a unified response to this issue.

Many federal, state, and local organizations have worked on reducing the number of MVCs and related injuries and fatalities and those efforts continue today. These programs have no doubt made a positive impact, but the number of crashes, fatalities, and total economic effect of MVCs are still far too great. According to the National Safety Council, total motor-vehicle injury costs for 2019 were estimated at $463.0 billion. Costs include wage and productivity losses, medical expenses, administrative expenses, motor-vehicle property damage, and employer costs.7 The total costs associated with fire crews responding to the 6.75 million MVCs annually are unclear, but one could assume they are significant. These costs would include fuel, wrecked apparatus responding to and returning from the scene, fire apparatus struck by vehicles while parked at the scene, injuries to personnel and their related costs, and line-of-duty death benefits. U.S. Department of Transportation (US DOT) fatality statistics from the first half of 2021, shows the largest six-month increase ever recorded in the Fatality Analysis Reporting System’s history.8

Technology

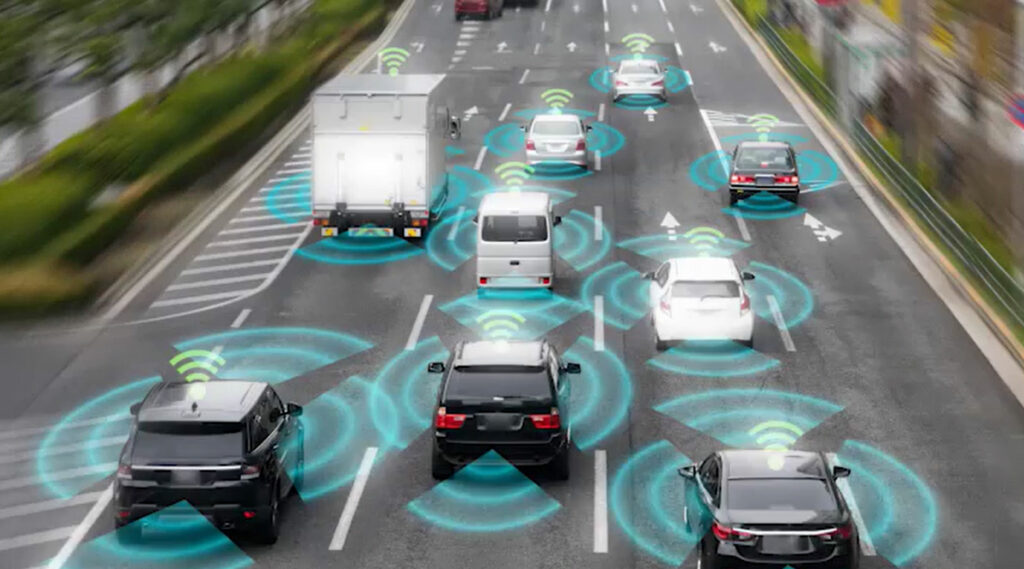

Technological advancements have presumably played a large role over the years in reducing the occurrence of fires and related deaths. These technologies likely include smoke detectors, sprinkler systems, automatic alarm systems, non-combustible building components, and safety improvements in consumer electronics to name a few. According to the U.S. DOT, connected vehicles could dramatically reduce the number of fatalities and serious injuries caused by crashes on our roads and highways.9 Safety systems such as seat belts, air bags, and electronic stability control help lessen the occurrence of MVC deaths. Continued work is needed in this area, but more focus needs to be on preventing the MVC from ever occurring in the first place. Current technology such as connected vehicles communicating from vehicle to vehicle, and vehicle to infrastructure (picture 2), autonomous emergency braking, digital alerting, intersection collision warning systems, forward collision warning, lane departure warning, lane keeping assistance, eye tracking technology, etc. have noticeable promise.

As humans, we are not without fault; just a split second of distraction, one bad decision, or simple human error can lead to horrific consequences. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), nine out of 10 serious roadway crashes occur due to human behavior.10 Another NHTSA study of connected vehicle technologies has shown that they have the potential to reduce up to 80% of crashes where drivers are not impaired, which would save a significant number of lives and prevent millions of crash-related injuries every year.9 Fully autonomous driving technology is still in its infancy. As failsafe systems are improved, redundant systems are developed, more advanced sensors are created, and artificial intelligence advances, autonomous vehicles will rapidly develop into a system that makes the roadway safer and more efficient for all. Reluctance or refusal to adopt this new and seemingly foreign technology may impede progress. Many successful field trials are needed before this technology is ready for mass adoption of fully autonomous driving. As this new technology comes to market and reluctance or fear starts to set in, think about just how much we already trust our lives to computer-controlled systems. One simple example is an elevator. Early elevators were manned by a human elevator operator that controlled every aspect of elevator’s function. Today, we trust a computer to perform all these functions. An underdeveloped or unproven elevator control system could lead to catastrophic incidents.

As technologies such as these and other future innovations become fully adopted, they will help the roadways become safer for all. Funding and systems must be established to accelerate development of these technologies, with the goal of implementing federal mandates to ensure these technologies are standard safety features in all new vehicles. The insurance industry could assist with adoption in both new and existing vehicles by offering discounted premiums. Tax credits could also be offered to assist with adoption.

What You Can Do Today

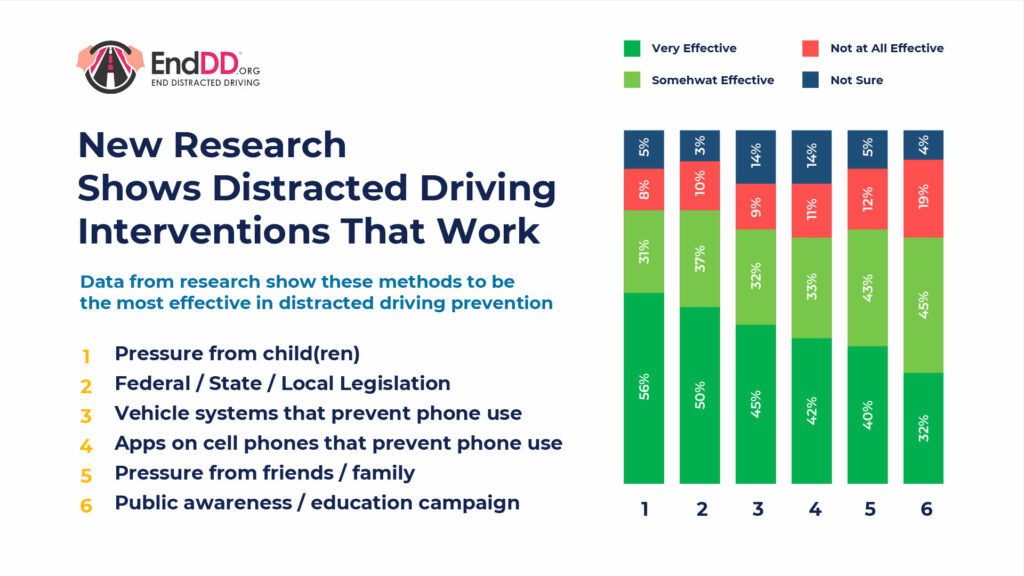

Many steps can be taken at the local level starting today. As we talk to our nation’s youth about fire safety, we can add topics such as the dangers of distracted driving. Not only will this pay dividends in the future when these children start driving, but research from EndDD.org shows that pressure from child(ren) is the most effective way to prevent adult distracted driving (Photo 3). EndDD.org and the ERSI are two organizations with public education material for distracted driving that includes material for elementary school ages. We should also start safe driving educational programs targeted at 15-, 16-, and 17-year-olds. Some of the topics to be covered could include distracted driving, defensive driving, the dangers of driving under the influence, inclement weather driving, seat belt usage, the dangers of speeding, and how to react to emergency vehicles responding to incidents or parked on the roadway. As effective as our fire safety educational programs have been, safe driving educational programs could be equally effective at relatively little cost other than some of our time. Delivery of these messages by local fire departments, who are highly respected and appreciated in their communities, could prove to be more effective than other traditional means of educating the public. Many videos and/or infographics are available online and free to distribute. I call upon you to start a campaign to distribute this information out regularly on social media channels and through public service announcements on local radio and television stations. It is important to remember that older drivers need to be reminded of safe driving practices. Develop grassroots initiatives to help address this issue in other new and creative ways.

Speeding, distracted driving, and driving under the influence (DUI) are often cited as the leading causes of MVCs. Ongoing driver education and awareness is needed on the dangers of these risky behaviors. The NHTSA document “Countermeasures That Work: A Highway Safety Countermeasure Guide For State Highway Safety Offices” describes proven countermeasures to address these and other highway safety problems. The CDC’s website houses an informative article titled “Motor Vehicle Crash Deaths – How is the US doing?” that describes some proven measures from the best performing high-income countries in reducing crash death rates. It would be prudent for jurisdictions to implement strategies such as these.

The creation of a report similar to America Burning would be only the first step. Adoption of recommendations and their implementation will have to follow with a concerted effort if success is to be achieved. Funding for a project of this size is likely to be the first hurdle. Allocation of new funding, or reallocation of existing funding will be needed. While this process will not achieve results rapidly, a well-thought-out plan with broad buy-in will likely pay significant dividends in the future.

The intent of this article was not to come up with all the solutions to this problem. The intent was to bring light to the issue and stimulate thought and desire to take action amongst the readers. As the roadway becomes more congested and more distracted, drowsy, drugged, drunk, and just plain dangerous drivers get behind the wheel, these issues are presumably only going to get worse. The fire service is uniquely positioned to help address this issue. We can’t afford to not take action.

References

1 “Traffic Safety Facts 2019”, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 8-2021, https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/813141

2 “LODD News”, Emergency Responder Safety Institute, https://www.respondersafety.com/news/lodd-news/

3 “U.S. Fire Deaths, Fire Death Rates and Risk of Dying in a Fire”, U.S. Fire Administration, https://www.usfa.fema.gov/data/statistics/fire_death_rates.html

4 “America Burning Study 40 Years Old: Forecast the Need for Better Fire Prevention and Codes”, Fire Engineering, 8-2021, https://emberly.fireengineering.com/fire-prevention-protection/america-burning-study-40-years-old-forecast-the-need-for-better-fire-prevention-and-codes/

5 “Motor Vehicle Crash Deaths – How is the US doing?”, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/motor-vehicle-safety/index.html

6 “Fatality Facts 2019 – State by state”, 2021, Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, 3-2021, https://www.iihs.org/topics/fatality-statistics/detail/state-by-state

7 National Safety Council, https://injuryfacts.nsc.org/motor-vehicle/overview/introduction/

8 “Early Estimate of Motor Vehicle Traffic Fatalities for the First Half (January–June) of 2021 “, U.S. Department of Transportation, 10-2021, https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/813199

9 “What Are Connected Vehicles and Why Do We Need Them?”, United States Department of Transportation, https://www.its.dot.gov/cv_basics/cv_basics_what.htm

10 “Automated Driving Systems 2.0: A Vision for Safety”, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 9-2017, https://www.nhtsa.gov/sites/nhtsa.gov/files/documents/13069a-ads2.0_090617_v9a_tag.pdf

BRADY ROBINETTE is a lieutenant with Lubbock (TX) Fire Rescue and a member of the Lubbock Fire Rescue Traffic Safety Committee. He has served for 14 years as a volunteer with Wolfforth Fire & EMS. He has an associate degree in computer science; is an advanced structural firefighter and advanced EMT; and is certified in swiftwater rescue, confined space rescue, and trench rescue.

LAN VENTURA is a graduate student in the Department of Civil, Environmental, and Construction Engineering at Texas Tech University. He has two years of experience in roadway design. He has a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering and is pursuing a PhD; is an Engineer-In-Training.