COMMUNICATIONS AT A HAZARDOUS MATERIALS INCIDENT

HAZARDOUS MATERIALS

A review of past major hazardous materials incidents reveals frequent problems with communications, the author reports. Keeping these tips in mind should help.

At a hazardous materials incident all levels of command receive information, make decisions, interact with many agencies and inform personnel of the decisions so that actions can be taken. Without a proper format and control of the communications process, command at the incident will not be successful.

Communications, then, must take place at several levels. It can involve several different methods, as long as the technique used meets the basic requirements of rapid, clean, easily understood messages. These messages can be transmitted by: radio on various frequencies, written messages, verbal messages via a messenger, and telephone.

Obviously, the radio is the most convenient and frequently used method. Unfortunately, with limited frequencies there is an overload and many important messages fail to get communicated. Personnel at the incident must constantly keep their messages, commands and reports short, clear and concise. In addition, the alternative methods listed above can be used to allow the radio channel to remain clear.

Communications need to occur between many levels of command at a hazardous materials incident. A diagram of the communications interaction is shown in the figure. It clearly shows the complexity of getting information disseminated at an incident.

Based upon the requirements of communications, the organizational structure needed for communicating can be developed. First, the problems must be broken down into small units and then each unit studied separately.

Last month in Fire Engineering, the three levels of hazardous materials incidents were discussed. The first level involves an incident which the local units could handle. The second level requires mutual aid, some specialized assistance from other local agencies and some reference information. Finally, the major hazardous materials disaster, involving many federal, state, local and private agencies constitutes the third level.

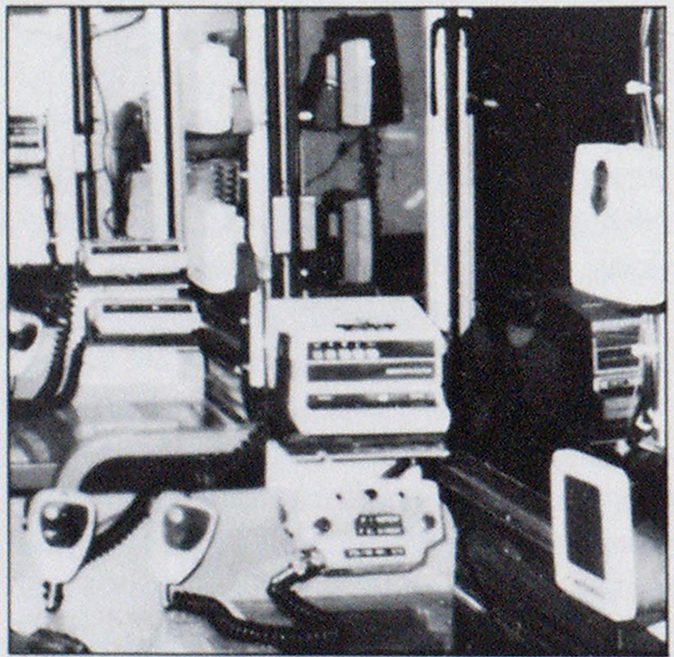

Photo by Scott Gutschick

At a Level I incident, the local units will be able to use their standard fireground frequency to communicate. Information can flow between the operating team, the apparatus and the dispatching center with little problem.

Level II incidents create a somewhat larger problem for local unit communications. Now mutual-aid companies are involved. As a result there will be interaction between the local units and the mutual-aid units. In addition, the various dispatching centers must be in contact to ensure coordination of resources.

The Level II incident requires that there be at least three radio frequencies —one for local to local, one for local to mutualaid, and one tor mutual-aid to mutual-aid communications. In this way, depending on where the command is going to or coming from, the units can interact directly without a middleman. In addition, the dispatching centers should communicate by telephone with a direct, dedicated line being the preferred method.

The Level II communications problems are further complicated by the variance in frequency bands used by different fire departments. Some are on low band VHF, others are on high band VHF and others are on UHF If regions do not attempt to agree on the general bands, then separate radios to talk to mutual-aid companies are necessary. This is much more expensive than adding another frequency to a multichannel radio.

If three radio frequencies are not available, a system of written message delivery needs to be developed before an incident occurs. Otherwise, the radio system becomes overloaded, important requests and orders go unanswered and the incident commander’s frustration level builds up.

For local and mutual-aid units at a Level III incident, the communications requirements remain the same as at a Level II response. However, there is the additional problem of additional communications with the command post. This is discussed below.

Care must also be exercised in the use of portable radios. In many instances it appears that they are being used to talk out the hazard instead of communicating information. judicial use of the portable to maintain an open channel for important messages is absolutely essential. Do not be a radio “litterbug.”

Dispatching center communications

The local dispatching center becomes the crossroads or hub for information flow, particularly during the initial stages. The dispatcher is the link from the field officer to the other units and the outside world.

A direct telephone link with the other dispatching centers that provide mutual aid is of great assistance. In addition, a resource manual for reference help, outside technical assistance, logistic support and preplans is very helpful.

A place for the operation of private radio nets should also be provided for in the dispatching center. Amateur radio operators through their RACES net and CBers through their REACT unit can provide supplemental radio traffic handling. They can set up portable units at the command post and evacuation centers and use a base station in the dispatching center. Use of these public service organizations is very helpful.

—photos by the author.

The dispatching center will need several outside lines also. Conversations will be necessary with experts on the technical aspects of handling the incident. Additional calls for items such as food, toilet facilities, heavy equipment, plugging and diking material will have to be made from the dispatching center. If there is only one outside line, communications can quickly bog down.

Remember, the operator at the dispatching center must maintain control of the frequency to ensure that priority messages get through.

Command post communications

A great deal has been written about the need for a command post and its staffing. However, all the world’s great brains, assembled in a single place, cannot do any good unless their suggestions and orders can be implemented. And they can only be implemented if they are communicated to the field commanders, so just establishing a command post is not enough.

At a Level I incident the command post will probably be the incident commander’s car. From here, the small number of support people can be together, communicate to the field units and see that the decisions are implemented.

For Levels II and III the communications problem becomes more complex. Now. more staff is needed at the comand post. The staff will quickly outgrow the incident commander’s car. What is needed now is a facility which can have the necessary radio, telephones, meeting areas and toilet facilities.

Sometimes the command post facility can be a building in the area of the incident. A school, church or shopping center could be used. However, base station radios and antennas would need to be controlled. This system works provided that extra base station radios are available, technicians are ready to install them with antennas quickly, and that there is a suitable facility nearby. Unfortunately many hazardous materials incidents do not happen at ideal sites to specifications the fire department would like to establish.

In response to this problem, many jurisdictions have developed a mobile command post. This technique allows the permanent setup of a radio system, a designated area for meetings and a telephone hookup. The mobile communications center does not tie up a motorized piece of equipment. A pickup truck is used to pull it to the scene and the pickup truck can serve multiple uses.

Radios that need to be installed to handle a Level II or III incident include those with frequencies for local fire dispatching, neighboring fire dispatching, mutual-aid fire departments, law enforcement, public works, local government, and amateur radio/CB radios.

In addition, there should be resource lists as well as the ability to connect telephone lines. This will reduce the requirement for radio communication between the dispatching center and the command post.

Remember, a member of the command post team must be the communications officer. It will be impossible for the incident commander to operate the radios at the command post. The communications officer should be responsible for all of the radio operations as well as securing operators for each of the frequencies used.

Planning

Obviously, all of the processes which have been described cannot happen unless some planning has been done. Procedures need to be established for the following communications responsibilities:

- Notification and response of mutual-aid companies.

- Procedures for operation on the various frequencies.

- Development of resource manuals.

- Procedures for contacting informational resources.

- Procedures for notification of regulatory agencies.

- Procedures for activation of a command post.

- Procedures for testing the communications preparedness of the community.

As a result of recognizing the problems of communicating at a major incident, several California fire departments have signed a joint agreement on the use of radio frequencies when the partner agencies are engaged in mutual aid. These agencies are: California Department of Forestry, California Office of Emergency Services, Los Angeles City Fire Department, Los Angeles County Fire Department, Ventura County Fire Department and the United States Forest Service. Each agency agreed to adhere to the requirements on the use of the frequencies and to cover mobile, portable and temporary base/ control station use. Standard clear word text and phrases were agreed to, so that communications between agencies was improved.

Thus, planning for the incident has helped those agencies in California prepare for the communications problems which can rise at a Level III hazardous materials incident.

Summary

One of the major keys to handling a Level II or III hazardous materials incident is effective communications. The incident commander must rely on information from supervisors in the field, must be able to get strategy decisions back to the field, and must be able to communicate with advisers. An effective system for accomplishing this does not just happen. It must be developed in advance, practiced, revised and then followed at an incident. Good and effective communications can spell the difference between success and failure.

CASE STUDY

A review of past Level III hazardous materials incidents usually disloses a problem with communkations. As an example, there was a train derailment in Rockingham, N.C., that was reviewed by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). The board reported how 29 cars of a 102-car Seaboard Coast Line freight train derailed in a remote area about 4 miles west of Rockingham The railroad track on a 40foot-high embankment bordered on a stream and a swamp. The closest occupied building was about a mile away.

Three of the derailed cars were carrying hazardous materials, including ammonium nitrate and natural uranium hexafluoride, classified as a radioactive material. On impact, four uranium hexafluoride cylinders broke away from their trailers and flat cars and were scattered north of the track. The car carrying the ammonium nitrate broke open and caught fire, and one of the uranium hexafluoride cylinders was in close contact with the fire, which spread to other rail cars loaded with combustible cargoes. The train crew reported the accident and fire to the railroad dispatcher at the Hamlet, N.C., terminal via VHF-FM radio.

Said the NTSB report:

During the emergency response at Rockingham, each of the on-scene entities operated independently. Furthermore, no representative from any organization assumed command of the overall emergency response and assured a coordinated effort. In their postaccident reports, both federal and state agencies acknowledged this command and coordination problem, and reported that communications in and out of the accident site were inadequate In addition, these agencies cited problems caused by the lack of visual means for identifying the individuals in authority and their functional responsibility.

Communications: All federal and state postaccident reports cited communications problems at Rockingham. Communications systems and procedures must be established and used effectively for adequate emergency response to a hazardous materials accident. The communications system should link the on-scene commander with on-scene emergency response organizations and with the external support agencies. To avoid confusion, the communications system should be under the direct control of the on-scene commander, and direct on-scene/external intercommunications should be kept to a minimum.

Command Post: The Safety Board could not determine if a command post was ever established for the Rockingham emergency. The Safety Board has noted in previous hazardous materials emergencies that a command post functions as a focal point to ease the transfer of information and facilitate interagency coordination. A command post should be immediately established upon arrival of the first emergency response personnel. The command post should be located so that it will not be threatened if the postaccident situation deteriorates. In addition, the command post would be in the focal point for coordination of effort and communications.