WHAT WE LEARNED ❘ By Josh Xenakis

On a Sunday last October, emergency units responded to a technical rescue call at a single-family residential structure on the west end of Virginia Beach, Virginia. At 1059 hours, Virginia Beach Fire Department Engine 9, Engine 35, Ladder 16, Rescue 1, Battalion 5, and the on-duty assistant chief were dispatched. An EMS case was also entered for the call with EMS Chief 10, EMS 3, and ambulance 923P responding.

Dispatch reported a 48-year-old male patient who was working to remove a tree from his backyard when he experienced a cardiac medical emergency. Engine 9 and Battalion 5 arrived on scene at 1102 hours and established command. Engine 9 confirmed that a male patient with a language barrier was stuck in a tree 35 feet up, with a medical emergency.

Battalion Chief Brian Sullivan, who was the incident commander (IC), sent Engine 35 and Ladder 16 to a street behind the dispatched location to assess whether they could access the tree from the C side with the aerial. Virginia Beach ladder trucks operate with 100 feet of reach. The distance from street access on sides A and C was well over 100 feet, and we needed a more in-depth rescue plan. The call was upgraded to a technical rescue response and Rescue 2 and Ladder 7 responded to assist.

Rescue 1 arrived on the scene at 1114 hours, and I met with the IC to develop a ground-based tree rescue plan. My crew and I made our way to the backyard and initiated a tree rescue. Master Firefighter Vincent Smith donned tree-climbing equipment, including tree spikes. He climbed the tree for patient and rescue assessment, making patient contact at 1130 hours. The patient’s medical emergency during the tree’s removal made our choice to spike the tree necessary for speed and efficiency (photos 1 & 2).

1. Master Firefighter Vincent Smith as he approaches the patient in the tree. (Photos by author unless otherwise noted.)

2. The tree-climbing setup that was used on the call, with tree spikes and flip lines.

Other approaches we could have tried include the following:

- Shooting a rope into the tree.

- Securing a high point and hoisting a rescuer to the patient or over the tree.

- Anchoring on the other side to establish a raising/lowering system.

Due to the language barrier, all patient commands needed translation through a family member who was on the ground, which added to the challenge of this rescue. Rescue 2 and Ladder 7 arrived on scene and integrated into the rescue by setting up a main line and belay line to lower the patient to the ground. The patient was wearing a Class II harness, which was intact. Smith established a high point in the tree to securely attach the main and belay line to for lowering. Ladder 16 and Engine 9 assisted with clearing the area of debris under the tree for safety while lowering the patient.

The patient’s condition began to deteriorate, and time was a critical factor. We decided to use the harness that the patient was already wearing, which saved valuable time. Smith inspected his harness to ensure it was in proper working order. All other equipment was inspected, and all carabiners were replaced as the ones he had were not rated. Captain Jon Rigolo of Rescue 2 oversaw the lowering operation, ensuring the safe descent of the patient. The patient was lowered to the ground and placed onto a stretcher at 1151 hours. Patient care was transferred to the ambulance, which transported the patient to a local hospital with an ST-elevation myocardial infarction, or STEMI (photos 3, 4, & 5).

3. Smith setting a high-point anchor greatly aided in patient removal. (Photo by Ray Smith.)

4. Loading the patient onto the rope system that was being controlled by the ground base crew. (Photo by Chris Stockhowe.)

5. The patient was lowered directly onto a stretcher and taken to a waiting ambulance.

Lessons Learned

Following are some significant takeaways from this rescue.

- Look for and identify resource needs as early as possible. This incident highlights the importance of recognizing resource needs early on. In this case, the IC quickly realized that the situation required more specialized assistance, leading to a timely upgrade to a technical rescue response. Identifying the need for additional units and expertise from the outset is critical to ensure the safety of the victim and the responders.

- Consider the first-arriving unit. At a tree rescue incident, the first steps you take should include the placement of a ground ladder to the tree (if possible) or aerial ladder if access will allow. This will speed up access to the patient by minimizing the climbing distance for the rescuer. Leave this up to the first-arriving engine or ladder to handle. Secure the ladder to the tree and ensure the patient does not attempt to jump down to the ladder.

- Remember the importance of effective communication. The patient faced not only a life-threatening situation but also presented with a language barrier. Effective communication under such circumstances is critical. Rescuers had to relay patient commands through a family member on the ground. But what if the family member hadn’t been there? This incident reminded us of the importance of having multilingual skills among the responders or the ability to work with interpreters to ensure clear and precise communication during high-stress situations. New cell phones can interpret different languages to help with communication and language barriers.

- Check for proper equipment and equipment inspection. This incident emphasized the importance of having the appropriate equipment for high-angle rescues. It was fortunate that the patient was wearing a Class II harness, which saved valuable time in this case; however, all other equipment needed to be inspected, and nonrated carabiners on the patient required replacing. Regular equipment inspections and maintenance are essential for ensuring the safety and effectiveness of rescue operations (photos 6 & 7).

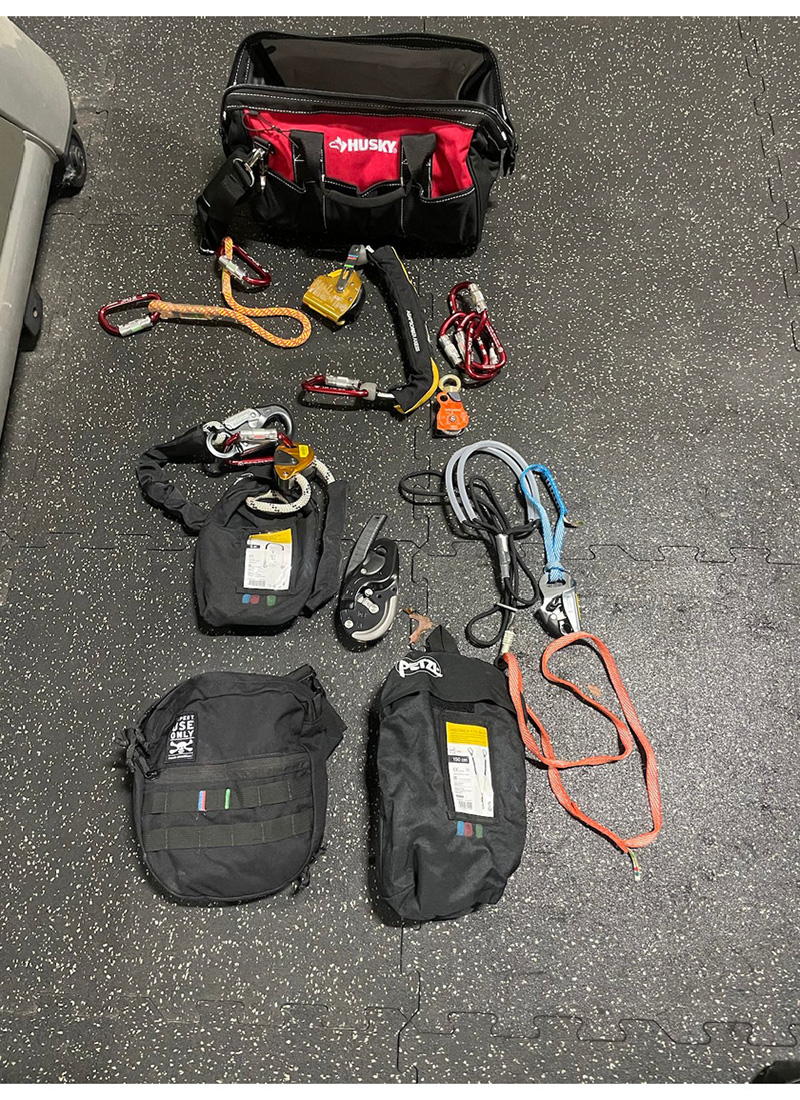

6. Personal rope equipment for each riding position.

7. Tree-climbing equipment kept on Rescue 1 and 2 in the Virginia Beach (VA) Fire Department.

- Ensure efficient team coordination. This was a key factor in the successful resolution of this incident. The integration of Rescue 2 and Ladder 7 into the rescue effort was seamless. It allowed for all crews to communicate and work together efficiently and safely. Proper training and effective coordination among team members are essential in high-stress situations.

- Be aware of time management and efficiency. This incident underscored the importance of efficient time management in high-angle rescues, where time can be a critical factor in a patient’s survival. Here are a few important timing notes from this incident.

- 52 minutes: Time from dispatch until the patient was on the ground.

- 14 minutes: Time from Rescue 1 arrival to accessing the patient.

- 35 minutes: Time from Rescue 1 arrival to securing the patient safely on the ground.

- Use local resources. Make a point to learn about the resources in your community. Train regularly with local arborists, whose crews often will have established certain prefire department arrival protocols. They may also have equipment that can help in a tree rescue operation that you may not have in your cache, such as large slingshots to launch leader lines or other items. Some teams may have all the necessary equipment, and some may not. Knowing where your team stands will help when the call for a tree rescue operation comes in.

Teachable Moments

This incident can serve as a valuable case study for emergency responders. It highlights the importance of successfully managing high-risk, low-frequency calls such as high-angle tree rescues. The successful resolution of this incident is a testament to the professionalism and competence of the emergency responders involved. The lessons learned from this rescue underscore the importance of early resource recognition, effective communication, proper equipment and inspection, efficient team coordination, and proper time management. They can also serve as valuable guidelines for emergency responders who may face similar incidents in the future.

JOSH XENAKIS is a captain on Virginia Beach (VA) Fire Department Rescue Company 1 and an NREMT-paramedic with 19 years of service. He has spent 10 years as a hazmat specialist, serving on a regional team for Virginia. He has an associate degree in emergency medical services. Xenakis served as a TEMS medic for 10 years for local and federal partners. He is also a member of the FEMA VA-TF2 USAR team and serves as an incident coordinator for Jacobs Engineering at Dugway Proving Grounds, in Utah, overseeing and facilitating CBRNE training.