It has been said that only three things happen naturally in organizations: friction, confusion, and underperformance. Everything else requires leadership.1

In a recent survey that included ranking the top 10 global trends, lack of leadership was number 3; 86% of the respondents cited a leadership crisis in the world today.2 We all pretty much agree that leadership is important and that, at least globally, there is a lack of leadership. “Leadership is not a talent you have or you don’t. In fact, it is not a talent. It is an observable, learnable set of skills and abilities.”1 Leadership has been a topic featured frequently on numerous Web sites and in books and articles and from many perspectives, including toxic leadership; servant leadership; leadership failure; and “how to lead” in general industry, in the military, and in the fire service.

RELATED FIREFIGHTER TRAINING

Learning Leadership by Observing

Dave Casey: Lead from the Right Seat

A Google search found about 8.850 billion results for “leadership”; 259 billion results for “fire service leadership”; 18 books on leadership just from Fire Engineering Books & Videos; and 77.6 million on “toxic leadership.”

(1) Leadership academies are becoming common for grade school and, in this case, Pre-K. (Photo by author.)

For the moment, let’s skip theories, war stories, and maybe some pontification. Let’s cut to the chase and ask two simple-sounding questions:

- What do you think are the qualities or attributes of a good officer?

- What do you think are the qualities or attributes of a bad officer?

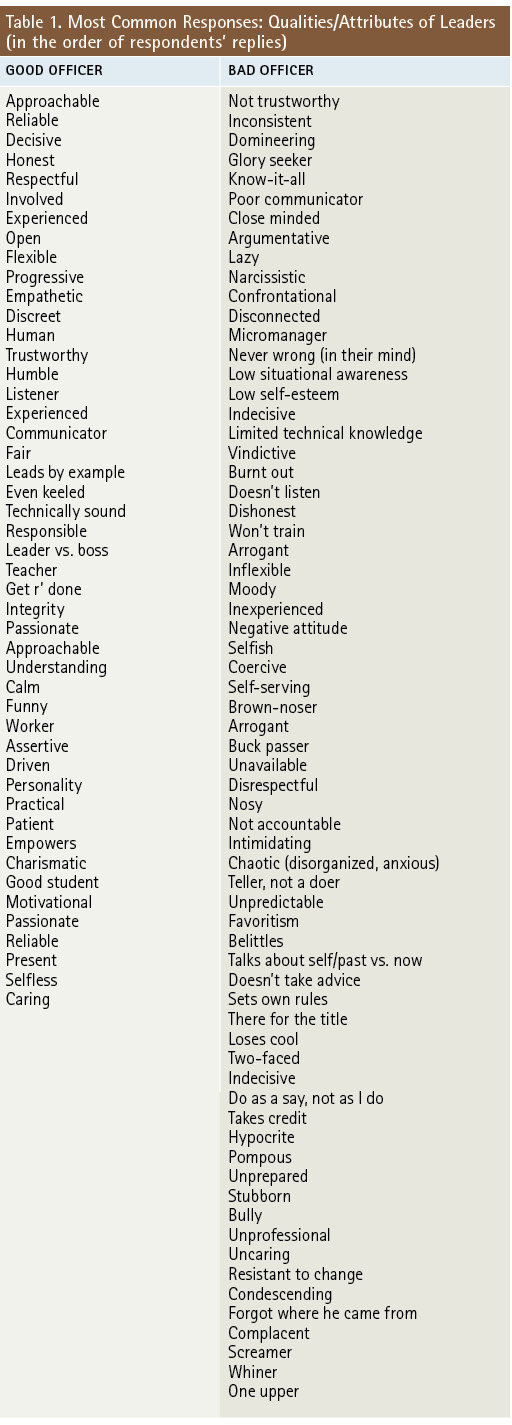

Chris Niebling, a retired fire officer and a 36-plus-year veteran of the fire service, and I have asked these questions of several hundred firefighters primarily in the United States and Canada during FDIC International classes and presentations and in a number of state, provincial, and local programs. Some of the most common responses are discussed here. Table 1 is a complete list of their responses.

A “good officer” has the following qualities: experience, skills and knowledge, physical capability to do the job, leads by example, is respectful to all, is a mentor, takes responsibility when things go wrong and gives credit to the company when things go well, shares the officer’s expectations of the company members and takes the time to find out what the company members expect of the officer, has integrity, is approachable, generates enthusiasm and teamwork, is assertive.

A “bad officer,” on the other hand, is a bully and confrontational; complains about getting no respect but shows no respect to subordinates, peers, or brass; is incompetent and complacent; is prone to anger; is a micromanager, doesn’t share knowledge or information; is unprepared; places blame when things go wrong and takes the credit when things go well; shows favoritism; is lazy; puts his interests above the crew’s; is not available for work or for calls; considers himself above the rules; is inconsistent; thinks he is never wrong; forgets where he came from.

An interesting observation Niebling and I made is that respondents in almost all of the presentations offered more negative qualities than positive ones. The negative qualities tend to cause more of an emotional response; hence, they are recalled more easily. It is easier to recall a situation that frustrated, angered, or hurt you than one that went well. Do you agree with the attributes and qualities offered by the participants in our surveys?

Let’s Make It Personal

How many of the qualities/attributes of a good officer do you feel are reflected in you? Likewise, how many of the attributes of a bad officer do you feel are reflected in you? Most excellent officers we look up to and depend on will have a couple of checkmarks in the bad column. The important lesson here is that if you see “bad” attributes reflected in you, you can work to minimize them.

Addressing Those “Bad” Traits

Ask trusted peers and subordinates about the items you have identified and see if their reaction is as definite or as harsh as your thoughts about yourself. If their responses are in agreement with yours, or at least not minimalized, see what to do about it.

When I was a young firefighter, one of my company officers was confrontational and had a quick temper. He complained about our brass, other company officers, and the subordinates he felt were not up to his standard in skills or abilities. He had experience, skills, knowledge, and physical capability and was quick to show you how to do things. If we messed up, he took the blame (“my crew, my fault”). When we did well, he gave us the credit. I learned many of my firefighting skills and most of my driver/operator skills from him. So, was he a bad officer or a good officer?

Supervising him was a nightmare, but if something difficult had to be done on scene, he and his crew were given the task (although you would hear about it later). Everybody knew his opinion, which was not always a good thing. When I was a chief officer in that department, I could always count on his pointing out any errors (or perceived errors) in my decision making. I had no worries of having an “Emperor’s New Clothes” issue. Again, did that make him a good or a bad officer?

If we are honest with ourselves, we will not find that all of our attributes will fall in the “good leader” column. That is true even for the “best” fire officer. The deciding factor here is that our good traits outnumber the bad traits. Otherwise, the firehouse’s morale will suffer, preparedness will falter or fail, and interest will wane. Personnel will look to move to other stations or a different department to get away from it. If you are viewed as a problem officer, you will lose opportunities that otherwise might have been available to you.

Officers and leaders are not made with a cookie cutter with everybody having the exact same way of carrying out their leadership duties. Conditions and situations will call for different leadership techniques. Effective officers will exhibit their positive attributes more often than their negative attributes.

Valued Leadership Qualities Have Not Changed

With all of the books, articles, blogs, and classes about leadership available right now, it is easy to assume that there is lots of new information. In many of those aforementioned sources, there is good, solid information often portrayed in new, more interesting, and easier to understand or apply methods. But, have the desires of the people being supervised changed?

During World War II, the soldiers and officers of a unit operating in France were asked this question: “What qualities, in your opinion, make a man a good leader?”3 (Remember, this was 74 years ago, and all of the U.S. combat troops were men). Their most common responses (paraphrased) follow:

- Thorough knowledge of the job. And, personnel must know that the leader officer has that knowledge.

- Fairness in all decisions.

- The ability to think clearly and make quick, sound decisions. Give orders with confidence even under adverse conditions.

- Calmness, even in the most trying circumstances. The officer should never appear excited.

- Personal interest in employees. Personnel should feel that their officer is interested in them, and the officer should do his best to help them and should stick up for them if the need arises.

- Trust of employees. Personnel must feel that they can come to the officer with issues. The officer should know each person and understand the job each person is assigned.

- Have the confidence and respect of the personnel. The officer should share their environment and work side-by-side with them in training and all activities. The personnel should think of the officer as “one of us.”

- Be compliant. The officer should do what he says and never tell his personnel to do something he is unable or unwilling to attempt. He should participate in the operations with the personnel and set the proper example.

- Encouragement. The officer should encourage and not nag.

- Mission orientation/situational awareness. The officer should keep the personnel oriented to their mission and situation.

It appears from this survey that the traits subordinates admire and seek in their leaders/officers have not changed very much over the years.

The “Bottom Line” of Successful Leadership

The goal of leadership is a high level of “combat readiness” (using a military term the fire service adopted). That high level of proficiency is a result of successful leadership, which includes motivated personnel who are trained and prepared. Everything else is distractions from or adjuncts to that goal. Leadership takes into account all the good attributes that add up to the three components of Combat Ready:

Highly Motivated + Highly Trained + Highly Prepared = Combat Ready

Ask yourself whether you, as an officer, are meeting that bottom line. If you are looking to become an officer, what will you do to meet that benchmark?

What Kind of Leader Do You Want to Be?

As already noted, how we access leadership information today has changed considerably; there are many more sources and several new methods that the soldiers of 75 years ago probably couldn’t even imagine.

Leadership is not a talent that you have or you don’t. In fact, it is not a talent but an observable, learnable set of skills and abilities.

Improving Leadership Skills

The phrase “natural born leader” has been around for decades and makes it seem that some people were born with natural charisma and leadership talent. But, realistically, these people have been exposed to good examples from which to learn, have often been mentored, and have learned the right information to be a leader. These influences could have been parents, Boy Scouts or similar organizations, or team sports. Many of these desirable attributes are under your control or at least within your grasp. Do we all wish we had a great mentor to guide us through the briar patch? Probably. But remember, an authentic mentor will let you fall into the briars until you figure out how to stay out of them. You can take many steps to become a leader or a better leader.

Read!

Look at some of the popular leadership books and attend the authors’ lectures if you can. Warning: Reading a book may enable you to “talk the talk” or at least mimic it; to “walk the walk,” you need to apply that information and those scenarios to enhance your experience, skills, and knowledge. Ask yourself, “What would I do?” “What would I say?” Apply this newfound knowledge to scenarios you can expect to encounter.

Train

You need training that has you making decisions like you will for real (simulations and exercises). Programs are out there. Attend the National Fire Academy and other training organizations.

Experience

This is easier said than done. But, you need experience, which can be gained from the above simulations and exercises as well as “riding up” in an acting capacity. Review incidents that you have been at and closely look at your and other people’s decisions. You are “learning by observing,” whether it is consciously or not. Watch interactions and actions by those you hold in esteem (and by those that you don’t); see what works and what doesn’t.4 As in the case of the books, put yourself in their shoes and determine, “What would I do?”

Once You Get the Position

Your work and learning do not stop when you get the promotion. Keep up with the trade journals and ask yourself, “What would I do in that situation if it happened here?” The more questions like that you ask, the better prepared you will be. The same goes for incidents your department responded to that you didn’t and your neighboring department’s incidents. Put some real effort into it to get good results. Place yourself as first due (second due, later); change things up; really put some thinking into this. Share with your company as a chalk talk or a table brief and get their input; not only your thoughts should be discussed.

Read more! Get beyond the technical textbooks used for promotional tests; look at the topic-specific books. A couple of books that I have read and with which I am familiar are the following:

- Step Up and Lead by Frank Viscuso.

- From Buddy to Boss: Effective Fire Service Leadership by Chase Sargent.

- Learning Leadership by James M. Kouzes and Brian Z. Posner.

Endnotes

1. Kouzes, James M and Posner, Brian Z. The Leadership Challenge.® Wiley: 2016.

2. Shiza Shalid. “Outlook on the Global Agenda 2015.” http://reports.weforum. org/outlook-global-agenda-2015/ top-10-trends-of-2015/3-lack-of-leadership/.

3. See “Learning Leadership by Observing,” Dave Casey, Fire Engineering, March 2016.

DAVE CASEY, EFO, MPA, CFO, served as Louisiana’s municipal fire training director and is managing partner of Ascend Leadership. He co-authored “The Right Seat” video series and the book Live Fire Training Principles & Practice. Previously, he was Florida’s state training director and the Clay County (FL) Fire Department chief. He was a firefighter at Sunrise (FL) Fire Rescue and at the Plantation (FL) Fire Department.