The Process of Making Decisions At Hazardous Materials Incidents

features

What happens when an alarm is received for an incident which involves the release or potential release of hazardous chemicals? Does the first-alarm incident commander decide to take the long way to the scene? Does he immediately submit a leave request so that he is relieved of potential decision-making responsibility? Well, these might seem like farfetched ideas, but really, how prepared is the first-arriving commander for handling an incident involving hazardous chemicals?

One of the basic problems is that the decision-making responsibility at a hazardous material incident is very different from handling a structural fire. While the basic goals of protection of life and preservation of property remain the same, the actual decision-making process is completely different.

The first-arriving commanding officer is experienced in handling structural fires because they occur frequently enough. But what about the hazardous material incident? The variety of chemicals and the potential locations of the incidents make them very different. The many varieties of chemicals and their combinations combined with the variations in locations and types of release make it almost impossible to develop experience and a cookbook approach to decision-making for the incident. Therefore, initial size-up and evaluation must be done in a systematic way so that the best response can be determined.

It is important for the incident commander to remember that at a hazardous material problem, doing nothing may in fact be the correct thing. The fire service has become involved in the incident because something has gone wrong, and that is certainly not the time to begin the study of the various methods and techniques for handling the incident. The initial arriving officer must be prepared in advance with the knowledge, information, and technique for mitigating the hazardous material incident.

Decision-making

Well, how does the initial incident commander organize his thoughts to begin a systematic analysis of the problem? The key here is the use of the phrase “systematic analysis.” If this is done correctly, it should minimize the confusion which accompanies many large hazardous material incidents. In this way, the chief officer can prevent mistakes and injuries while taking corrective action.

Basically, the decision-making process involves the following steps which must be considered:

- Is there a chemical hazard?

- If there is a chemical hazard, what is the product?

- What hazard does the identified product present?

- What objectives have been established by the first-arriving chief officer?

- Of the established objectives, what are the alternatives for accomplishing them?

- Which alternative is the best?

- Once the alternative has been implemented, is the decision correct or does it need to be modified?

- When the incident is concluded, have personnel and equipment been decontaminated correctly?

The first step in the decision-making process for the initial arriving chief officer is to determine if, in fact, there is a hazard at the scene of the incident. Input for this decision comes from many sources, including:

- Preplan information.

- Placards on the sides of the transporting vehicle if it is a transportation incident.

- A label on the outside of the shipping container.

- An NFPA 704 symbol on the outside of the storage container.

- The shape of the container, which may indicate a pressurized vessel or a specific type of chemical.

- Observation of physical characteristics, such as the color of the storage container, an odor from the spill or leak, or a vapor cloud rising from the area of the incident.

Preplan information is obviously extremely important. It is necessary for fire service personnel to get out into the community to determine the type and location of hazardous materials. In addition, special preplanning must be done for the various transportation routes through the jurisdiction. For highway transportation, highway access, terrain, water supply, and a general idea of.the commodities transported need to be developed. The same information can be prepared for railroad transportation with the added problem that access to portions of the track may present certain difficulties. Fire officers must also remember that water transportation and pipeline transportation must be included in their preplanning efforts. Finally, transportation by air needs to be considered not only for airports in the immediate vicinity, but for an incident involving an aircraft while traveling through airspace over the city.

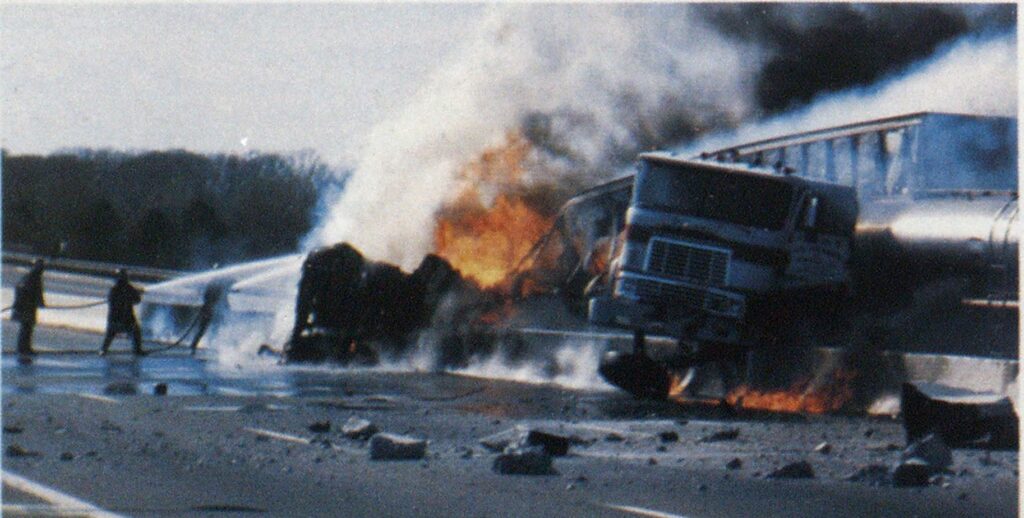

photo by Curt Hudson.

Weakness of labels

Placards and labels can provide general information about the hazard. The chief officer must remember that the rules governing the use of this type of warning system are complex. For example, on truck transportation for many commodities, it is necessary only to placard the truck when carrying over 1000 pounds of the hazardous material. Obviously then, the initial warning would not be present on the outside of the vehicle if only 900 pounds of a poison liquid were contained inside. It is also important for the officer to note that federal regulations require only one label on the outside of the shipping container. Thus, if the shipping containers are stacked one on top of another, the warning label may in fact not be visible.

There is a new placarding requirement for bulk transportation which involves the use of a four-digit United Nations number. The requirements and utilization of this kind of placarding are discussed further on.

The NFPA 704 symbol is a voluntary system for fixed storage devices. The system using numbers from zero (no hazard) to four (highest hazard) provides immediate information on the health, flammability and reactivity problems of the product stored. However, note that there is no way that this system can provide the specific name of the product.

The shape of the container may provide certain basic information and indication that there is a chemical hazard. Pressurized cylinders generally have rounded ends because of their ability to hold pressure. Relief valves can generally be seen on larger pressurized vessels. Some storage tanks, such as for cryogenics, have specialized shapes which can be easily identified. Other things, such as the shapes of specific types of rail cars, can indicate that the container is for a hazardous chemical. It is important to remember that the shape of the container can give only a general idea about the potential problem and cannot be used as a specific guide to the product contained.

DECISION-MAKING FOR THE FIRST-ARRIVING CHIEF OFFICER AT A HAZARDOUS MATERIAL INCIDENT

Wide World Photos

Finally, the initial chief officer can use his senses to determine a potential problem. The presence of an odor- particularly if it is irritating-or a vapor cloud, or a special color to the spill can indicate the presence of hazardous chemicals.

Remember, in this first step the chief officer is only making a determination that there is, in fact, a chemical release or potential release and that a hazard is present.

Product identification

Once the chief officer has determined that a hazardous chemical exists, the next step is to identify the product. It is necessary to know the specific chemical name if further information is to be obtained. Input for this decision is obtained as follows:

- From the shipping papers if the incident involves transportation.

- From plant personnel if fixed storage is involved.

- From preplans developed by the fire department.

- From placards if the United Nations number is shown.

- From markings on the outside of the transporting vehicle or the storage container.

The transporting vehicle carries shipping papers which may indicate the specific chemical name of the product. In rail transportation, the shipping document-called a waybill-is carried by the conductor either in the caboose or the engine. In truck transportation, the shipping document-called a bill of lading-is kept by the driver in the cab. When the driver is absent from the truck, the shipping documents should be placed on the driver’s seat. In air transportation, the air bill is kept by the pilot.

Manifest aboard ship

For water transportation, the master or mate of the ship carries the dangerous cargo manifest in the pilot house. On unmanned barges, a cargo information card is mounted in a cylinder near a warning sign which indicates that the barge contains dangerous cargo. Each of these shipping documents has the shipping name of the product as well as an indication that hazardous materials are contained. However, it is important to remember that some product shipping names can be a broad generic category such as flammable liquid N.O.S., which means flammable liquid not otherwise specified. In this particular case, the specific chemical name will not be obtained from the shipping documents and other sources must be sought for assistance.

On some rail shipping documents, an additional number can be found which is known as the standard transportation commodity code. The STCC is a seven-digit number assigned by the railroads and used throughout the United States. If the rail waybill contains this number and the first two digits begin with 49, it indicates that the product is a hazardous material. There is a reference text available from the Bureau of Explosives, Association of American Rail Roads, 1920 L St., N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036, entitled “Emergency Handling of Hazardous Materials in Surface Transportation,” which provides a cross-reference from the seven-digit number to a specific commody name and a recommended action guide for emergency response personnel.

Also on the shipping document, and possibly on a placard for bulk transportation, is the four-digit United Nations number. This number assigned by the Department of Transportation to all regulated hazardous chemicals shipped in commerce provides the specific name of the product. The conversion from the four-digit code to the specific commodity is contained in the Department of Transportation book, “1980 Hazardous Materials Emergency Response Guidebook.” Copies of this reference guide are available from the International Association of Fire Chiefs, 1329 18th St., N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036. Remember, the four-digit number will be shown on the placard only in certain instances when bulk cargo is being transported.

Employees can help

Plant personnel can be useful in providing information on products stored or used in processes in their facility. Usually up-to-date inventories are maintained. However, for early morning incidents when plant personnel are not usually available, it may be some time before this specific information can be obtained. However, the first-arriving chief officer must make every effort to determine the specific name of the commodity.

As indicated in one of the preceding paragraphs, preplan information specifically for maintaining a list of the hazardous commodities stored, utilized, or transported through a community can provide immediate information. It is difficult at off-duty hours to try and obtain this information from other sources. Therefore, a technique for preparing, maintaining, and updating this preplan information needs to be developed.

Finally, markings can be used in some instances to determine the specific commodity. Certain products must be identified in 4-inch-high letters on rail cars. For example, liquid chlorine rail cars, in addition to having a placard, must say that it is liquid chlorine on the outside of the rail car. The Department of Transportation requires these markings on 43 different chemicals. In addition, there can be markings with the name of the chemical on the outside of the shipping container. For example, a propane cylinder in addition to being marked a flammable gas can have a label on it that says propane. It is, therefore, necessary for the first-arriving chief officer to determine if any markings are visible. Remember that getting too close to read the labels may present safety hazards to the personnel under your command. A pair of binoculars is extremely useful in assisting in this step of the decision-making process.

Product hazard

Now that the product has been specifically identified, it is necessary for the first-arriving chief officer to determine the specific hazards which this chemical presents. Because there are over 35,000 different hazardous commodities produced by chemical companies, it is impossible for an individual to know how to handle each and every one. In fact, many of the major chemical companies have individuals who are expert in only three or four specific chemicals manufactured. They, too, find it impossible to know everything about all the chemicals produced by their own companies. It is, therefore, necessary for the firstarriving officer to be able to obtain information on the specific hazards from other sources.

Input for this decision-making step must come from:

- Reference books.

- Technical resources.

- CHEMTREC.

- Manufacturer.

- Shipper.

- Carrier.

There are many different reference books available for use at the scene of a hazardous incident. Two of these have already been mentioned. The key to selecting a good reference book involves the immediate information which can be provided to the first chief officer. However, care must be exercised to ensure that too many reference texts are not carried. Otherwise the chief officer will find himself pulling a large bookmobile behind the command vehicle and researching the chemical in several different books, finding all kinds of conflicting and differing data. Several texts which might be considered by the chief officer for reference include:

- The small-sized edition of Volume I of the CHRIS Manuals from the Coast Guard that is entitled “A Condensed Guide to Chemical Hazards.” It is available from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402.

- The National Fire Protection Association’s “Fire Protection Guide on Hazardous Materials,” available from the National Fire Protection Association, Batterymarch Park, Quincy, Mass. 02269.

- “The Fire Fighter’s Handbook of Hazardous Materials” by Charles Baker, available from Maltese Enterprises, Inc., P.O. Box 34048, Indianapolis, Ind. 46234.

- The “Farm Chemical Handbook” is very useful for fire departments which protect agricultural areas and could possibly be involved with the release of these types of chemicals. It is available from Meister Publishing Company, 37841 Euclid Ave., Willoughby, Ohio 44094.

- For a guide to the emergency medical service problems and treatment of exposure to hazardous material incidents, the chief officer should reference the NIOSH “Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards,” which is available from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Center for Disease Control, NIOSH, Cincinnati, Ohio 45226.

Other resources

Other information on the hazard can come from technical resources which have been planned in advance. For example, there may be individuals in your community who have working knowledge of many different types of chemicals. These individuals should be approached to determine if they are willing to provide assistance to you as the chief officer should an incident arise in the community. Telephone lists must be continually updated to ensure that they are current.

CHEMTREC provides a 24-hour, seven-day-a-week, toll-free number to provide information on the chemical hazards of specific products. CHEMTREC can be reached from the continental United States by dialing 800424-9300. From Alaska and Hawaii CHEMTREC will accept collect calls by dialing area code 202-483-7616.

To provide assistance, the CHEMTREC communicator will need certain basic information from the caller. In addition to the product name, information on the shipper, manufacturer, container type, the rail car number or truck number, the carrier name, a description of the problem, and a location of the incident will be necessary. Once given this basic information the communicator will provide the fire service caller information on the specific product. To assure accurate transmission of information both to CHEMTREC and back from CHEMTREC to the field incident commander, the fire department should establish a standard set of forms which include the data to be given to CHEMTREC and the format of the data which CHEMTREC will provide. Sample copies of these forms can be obtained by writing the author.

The manufacturer, shipper, and carrier are places that provide information on the specific hazards and suggestions on how to handle the incident. Some manufacturers, shippers, and carriers also maintain response teams which can be activated through CHEMTREC for direct assistance on the scene. In addition, several chemical groups have developed interagency response teams so that the nearest chemical company will respond to an incident even though it is not their product which is posing the risk. For example, the chlorine manufacturers have organized a group called CHLOREP. This team, activated through CHEMTREC, will send the closest available response group for a chlorine incident no matter who the original manufacturer or shipper of the product is. The individual response teams from these groups contain knowledgeable individuals who will come to the scene to provide assistance and advice to the incident commander. The only difficulty will be in the time it takes them to get to the scene.

Establishing objectives

Now that the incident commander has determined the specific product involved in the incident, the objectives for mitigating the incident need to be established. The areas of concern for the initial arriving chief officer involve:

- Rescue.

- Exposure protection.

- Evacuation.

- Water supply;

- Containment.

As in all incidents which the fire service responds to, rescue is the primary objective. However, because a hazardous material incident is special, the incident commander needs to make several evaluations before rushing to effect a rescue. If the product presents severe health hazards and special protective equipment is required but is not available, should the risk of endangering additional personnel be taken? Should the incident commander ask himself, “If by attempting the rescue, will matters be made worse and will the individuals involved become an additional part of the problem?”

It is necessary for the first-arriving chief officer to face the fact that there will be some incidents where rescue efforts cannot be made until special protective equipment is obtained. This is a judgment decision which becomes extremely difficult. While some risktaking is necessary, is it justified to risk the fire fighters in a given circumstance? The special protective clothing necessary may be obtained from outside resources or from a local specialized hazardous response team.

Hazardous material incidents also create specialized emergency medical service requirements. If the EMS service is part of the fire service and under the command of the initial chief officer, then what specialized equipment and protective clothing do these individuals have available?

During the treatment of personnel exposed to hazardous chemicals, will additional exposure occur to the EMS personnel? Will they, too, become part of the problem and not part of the solution? What specialized care is necessary for those victims who have been exposed to the chemical? Have the EMS personnel obtained the necessary training to handle this specialized kind of problem?

Rescue needs

Rescue may also involve the need for specialized heavy-duty rescue equipment. As in the handling of the emergency medical service problem, these individuals also need specialized protective clothing for working in a hazardous environment. Training with the equipment is an absolute essential for handling a major accident involving the release of chemicals.

As in structural fire fighting, exposure protection is one of the major concerns of handling a hazardous material incident. To establish an objective for the protection of any exposures, the firstarriving chief officer must answer the following questions:

- What are they?

- Where are they?

- How can they be protected?

- What are the risks of protecting them?

In answering each of these questions, the incident commander can then establish specific objectives for protecting exposures. Remember that it may be necessary to provide for life safety and removal from exposures without the capability for preventing damage to them at some future point in the incident.

Evacuation decisions are very complex. Initially, the first-arriving chief officer needs to determine the immediate danger area. Civilian personnel must be removed quickly before the incident escalates. In addition, a further evacuat ion of the vicinity may be necessary based upon the circumstances of the incident. Suggested evacuation distances are contained in the Department of Transportation “1980 Emergency Response Guidebook.”

Evacuation questions

The questions which will lead to the establishing of objectives for the evacuation requirement involve:

- Who will accomplish it?

- Where will the evacuees go?

- How will the evacuees get there?

- How will you handle the nonambulatory evacuees?

- Who will care for the evacuees?

Another requirement before the objectives can be established is to determine what water supply is available. While some chemicals are reactive with water, it is still the best means for providing for mitigation of the hazardous material incident. The questions the first-arriving chief officer must answer are:

- Where is the water located?

- Is there sufficient apparatus to provide water from the source to the scene?

- Is there sufficient water available from the source to handle the incident?

- Is a back-up water source available to ensure continued supply?

The final item which needs to be considered to establish the objectives involves containment. A hazardous material incident needs to be contained to prevent the escalating of the problem. Containment can be accomplished if the chief officer answers the following:

- How will containment be accomplished?

- What equipment is necessary to contain the spill or leak?

- How long will it take to get the equipment to the scene?

Alternatives

With the objectives established, the first chief officer must review the alternatives for solving these objectives. Input for determining the alternatives will come from several sources. These include:

- The type of incident (spill, leak, or fire).

- The state of the material (solid, liquid, or gas).

- The hazard of the material (flammable, health, explosive, radioactive, reactive).

- The terrain (distance to exposures, natural conduits, man-made conduits).

- The time (slowly by a spill or leak; rapidly by explosion).

- Life hazard (high, medium, low).

With this kind of input, the chief officer must determine the alternatives for controlling, extinguishing, or protecting life and property while withdrawing and evacuating. The techniques then used for the various alternatives will depend on all the information gathered in the decision-making process to this point.

Control can be accomplished in many ways. The spill, if it is a solid, can be covered with sheeting while a watersoluble flammable liquid can be diluted with water. In fact, some material may even be picked up, or if stored in containers, removed from the hazard area. Diking can be accomplished with sand, dirt, or special diking material available from various suppliers. Foam can be used to cover flammable liquid spills to reduce vapors and, in fact, special chemicals can be used to reduce the flash point or to convert a liquid into a semisolid, less-likely-to-run material.

If extinguishment is chosen as the alternative, the correct agents must be used. Vapor dispersion must be accomplished if a flammable liquid is involved. In addition, before extinguishment occurs, the chief officer must assure that there will no longer be continued leakage of vapor.

One of the hardest alternatives to select is to protect life and property while withdrawing an evacuation. This temporary holding action is foreign to many fire service personnel who have spent entire careers in an action-oriented position. However, as indicated previously, a hazardous material incident is unlike a structural fire, and it may be the best course of action to select this alternative.

Once all of the evaluation has been done, the objectives set and the alternatives considered, the chief officer must then make the final selection. Which alternative is best for the given incident? Certainly in the first minutes of arrival on the scene of a hazardous material incident, the information continues to flow to the commander. On the basis of the information immediately available, the best alternative is selected. However, remember that this is a continuing evaluation process, and as more information is received, as the alternative selected proves not to provide the best solution, reevaluation must take place.

Reconsider alternatives

Based on the reevaluation, another best alternative can be selected. Remember, making a change is not an error. It is an important part of the process which must be considered. Chief officers should not put on blinders, make a selection, and go down the road toward a solution without ever reconsidering that decision. A hazardous material incident is a very dynamic situation which continually changes. No one decision should be considered “the answer.”

When the incident is concluded, remember that cleanup of personnel, apparatus, and equipment must be accomplished. It would be a shame to have successfully handled an incident with all the specialized protective equipment necessary without injury and then return to the fire station and have the fire fighters exposed to the chemical residue while handling their clothing or apparatus. This is an important step in the entire decision-making process which cannot be eliminated.

The first-arriving chief officer has a great deal to think about. A lot of decisions must be made quickly. Information needs to be provided to the command post quickly and correctly. Only with correct and good information will the incident commander be able to make decisions at a hazardous material incident. These decisions need to be based upon a systematic analysis and must be continually practiced and worked with if they are to be successful. A haphazard procedure can lead only to injury, confusion, problems and an escalation which will harm the community. Be prepared to handle the hazardous material incident in your jurisdiction.