BY NICHOLAS F. NANNA

The art of incident command has generated a substantial review and discussion. However, the actual basic processes have not been subject to sufficient peer review. Below, I discuss the four primary models of on-scene incident command: mobile, forward, fixed, and major incident command support. Each has unique capabilities and attributes that facilitate the command and control of emergency incidents.

- Command Vitality

- A ‘Small’ Incident That Needed a Major Response

- Command and Control of Multiple-Alarm Fires

- Building an Efficient Incident Command Team

The Art of Command

To implement a model of incident command, it is essential to understand the definitions of command and control. These two terms are often confused and conflated; however, commanders should understand each model individually, and then the complementary interaction of the two becomes apparent.

Command is a designated officer’s legitimate exercise of authority to accomplish a task or mission.1 Inherent in the exercise of command is the legal authority to direct the operations of subordinates and require their compliance. An essential command attribute is the legal responsibility of the incident commander (IC) to operate in a professionally competent manner and make reasonable decisions in the exercise of his authority.

Control is the management of the tools and techniques of deciding and transmitting directions to assigned units. It is the ability to receive reports, develop an understanding of the situation, create and implement plans, evaluate the success/shortcomings of these plans, and adjust the goals as necessary. Incident command addresses the span of control. Still, the environment and unforeseen developments in an emergency incident in time and space are also critical factors in creating the model of command designed to manage this control and exercise command.

The Command Post

The principal tool for the IC to exercise his command and control responsibilities is the command post (CP), where he directs the strategy of the incident.Establishing a functioning and flexible recognizable CP provides adaptability to meet the changing situation and provides clear direction from the IC, through the incident command system (ICS), to each member operating and supporting incident mitigation.

The CP may be an IC’s pocket notebook and pen or a specialized vehicle costing many thousands of dollars staffed by the full complement of the ICS branch personnel. It is the IC’s incident analysis, which considers the incident’s complexity, the life hazard, the environmental conditions, the location’s accessibility and identifiability, and observation and communication variables.2

The Four Models of Incident Command

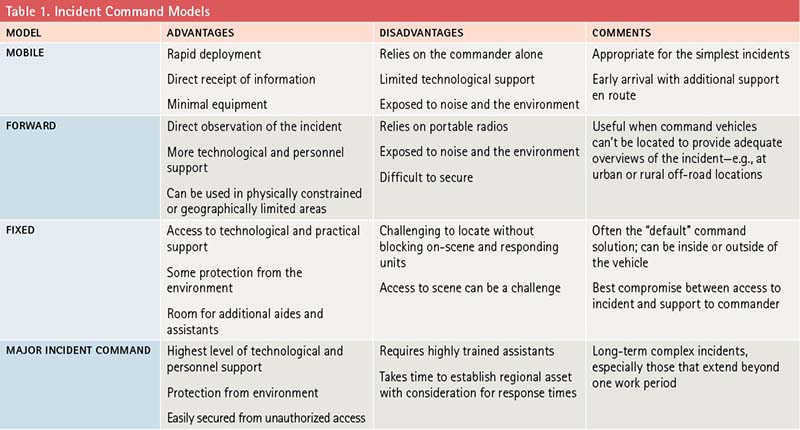

The four major models of incident command—mobile, forward, fixed, and major incident support—are in order from the least challenging to the most involved and complex incident. Much as incident command is scalable as incidents mature and information received and analyzed reveals each incident’s challenges, ICs can expand and contract these models as the incident variables dictate. Since an unexpected development can escalate even a bread-and-butter incident, the IC should anticipate and continually evaluate the need to escalate the command model. Each model has distinct material and personnel requirements; escalation will challenge the IC’s skills, education, and experience. According to an accepted crisis management theory, the IC is fighting the incident as it will be in the future while the company officers are fighting the incident as it is. Resource management is also a part of considering whether to step up the incident command model.

Mobile Command

Mobile command is at the lower end of the incident command models. The IC is on foot at the incident. Moving around the scene as needed to gain visual clues and directly influence subordinates’ actions, the mobile IC seeks understanding through personal observation.

In mobile incident command, the IC often uses a small board to record assignments; list tasks to be accomplished and note that they have been assigned and executed; and track the resources committed, available, and en route. The primary control tool is personal direction and a portable radio used to transmit orders and receive reports.

Although this model enables the IC to seek needed information and “manage by walking around,” there are inherent limitations. The IC is generally restricted to operating on one communication channel. The noise and the environment can interfere with the send-receive-understand communication process. The mobile IC has a limited field of view, and the nature of human focus can potentially overemphasize what is seen and sensed and minimize the information reported from outside the IC’s experience. The narrow perspective of the mobile IC can reinforce confirmation bias.

Mobile command may be appropriate for a geographically constrained incident that is not immediately assessed as complex. It may be the first-arriving command officer’s command model as he attempts to gain immediate situational awareness. In those cases where initial tasks challenge first-arriving units and they can’t provide adequate size-up, the mobile IC can conduct a personal reconnaissance while still exercising command and exerting control. Except for the least complex incidents, this model will generally evolve into forward command.

Forward Command

In forward command, the IC establishes a CP where it affords direct visual incident observation. This model most often occurs where physical constraints prevent the siting of a command vehicle such as a chief’s vehicle or another communications asset. For example, it is used in an urban area where apparatus block out or obstruct the command vehicle or the view from it or in suburban or rural areas where the topography prevents locating a vehicle advantageously.

Forward command will often use a portable command board in a suitcase container, which can be set up and provide the tools needed to track assignments, monitor resources, and direct tasks and their accomplishment. These portable command kits are more comprehensive than a handheld board and provide a stable surface on which to manage an incident. Often these kits are designed to allow for personnel accountability report tags, a graphic incident scene portrayal, and the initial incident command plan.

Forward command can provide space for additional portable or mobile radios to enable using different communications channels—e.g., command, operations, safety, and water supply. ICs will find it highly advantageous to employ additional command personnel—e.g., a command support technician or command aide or additional command officers to assist in managing the mobile board’s multiple communications and recording functions. In addition, at forward command, the IC can locate technology such as a drone download station, a portable weather station, and other electronic command tools.

Forward command facilitates direct incident observation while providing more tools and resources to the IC. It can still enable the personal direction of incident mitigation actions while creating a stable command post. Adding “pop-up” style shelters can create an environment out of inclement weather. Setting up and managing these position improvements will require additional human resources. No matter how developed these CPs become, they will still be susceptible to the noise and environment and subject the IC to multiple interactions with firefighters, medical personnel, and bystanders. It is essential to limit noise and interruption by restricting open access and delineating a perimeter for command and communication personnel.

This model of incident command relies on using portable radios, which can generate a limited amount of undistorted volume and a limited amount of power, which can be especially problematic in a nontrunked system. Using headsets can help personnel hear the working crews’ transmissions better, especially those on air in an immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH) environment.

Fixed Command

Fixed command is the model most often used in incident command. Since the inception of ICS, this model has been the subject of continual experimentation and discussions. Fixed command relies on a dedicated vehicle equipped with specialized equipment to facilitate command and control. Using this command model depends on finding a location that offers a good view of the overall situation that is also out of the way of incoming or retiring apparatus. Ideally, the IC will have a view of two sides of the incident. The roads or trails that lead to an incident must be sufficiently developed for the vehicle to access.

Often the rear of a chief’s or command vehicle will have a command package of mobile radios, incident command boards, personnel tracking tools, and other technological and practical accessories that support the exercise of command and control. These tools can include mobile radios, which have more power and have remote speakers to facilitate hearing transmissions.

Incident command boards should include spaces for noting units responding and on the scene; for noting common task management (assignment, progress, and completion); and additional resources to call including utilities (gas, electric, and water), police, building inspectors, the Red Cross, and other community organizations and services. The fixed command can include computer support to record incident plans and save them for after-action reviews.

The vehicle provides space for preplans, emergency response guides, standing operating procedures/guidelines, contact lists, and other reference materials. Lighting is available for night operations, and other accessories and storage are easily accessible.

Chief’s Vehicle

There are two models for using the chief’s or other command vehicles. An IC can remain in the front seat or operate on the tailgate using a dedicated command platform. In the first option, the IC has access to vehicle climate control and can isolate background noise by opening and closing the windows to quickly receive door-side face-to-face reports. But using the seats restricts how many people can assist; at most, only one assistant can sit in the vehicle to monitor radios and keep records.

At the rear of the vehicle, operations can take advantage of the command cabinet, have more room to move around, and interact more with crews and command assistants. Of course, in this model, environmental concerns enter into the decision matrix since cold/heat, rain/snow, and other conditions can be only partially mitigated. This location is more open to noise and confusion, including the many individuals who will want to talk to the chief, some who have vital information and some who do not. It can accommodate more than one CP assistant if needed. It is possible to have a more interactive exchange with sector supervisors, rapid intervention team officers, and other critical personnel.

Major Incident Command Support

Major incident command support most often uses a specialized CP designed for managing complex or long-term incidents. These CPs may use a vehicle specifically designed for this purpose or, in the case of area command, may use a fixed location such as a building or other structure.

These CPs can provide significant technical support, including drone downlinks, multiple radios for communications with supporting agencies, mutual-aid resources, visual and low-light video cameras, and lighting often provided on roof-mounted booms that can be linked to recording devices. Cell and satellite phones provide stable communications. Local and satellite television can provide outside data points, and computer support can include scanning and printing capabilities. A local weather station can provide temperature, humidity, wind direction and speed, and other data valuable in multiple types of complex incidents. Finally, a method of recording radio traffic is essential for various purposes.

Dedicated primary command vehicles can provide room for the incident command staff. In addition, they may offer multiple positions for planning, logistics, and finance sections and for public information and liaison officers. The increased communication and coordination burden will require multiple additional personnel and aides, who will need to be trained for these positions.

Some larger vehicles may offer a room or area for conferences and meetings. Given the long-term challenges of the complex incidents for which these are designed, it is important for ICs and their staff to get away from the cacophony of operations to assess progress and plan for the next rotation or work period.

The costs of procuring and maintaining these vehicles, along with the high level of technical training required to provide these command platforms, will often dictate regional resource sharing. Additionally, the complexity of setting up these CPs will dictate the level of incident for which they are called.

The physical advantages of this type of command include a climate-controlled, well-lit platform with a plethora of assets to support command and control. However, it can also isolate the IC from the incident and force him to rely on technology to maintain situational awareness. In these cases, the IC needs to physically review the incident periodically to supplement the picture of the incident presented with his own firsthand observation.

Whichever model you use, and however you scale it up or down, none of the models will be optimally effective without training. The training of the ICs, CP staff, dispatchers/communicators, and unit/sector leaders must be realistic and follow a building block progressive model.

Although it is good to start with tabletop exercises and computer simulations as the basic starting blocks, working a live incident with extreme weather conditions and a confusing, noisy environment will provide the adversities a team must learn to overcome. Every company/department drill and burn should be leveraged as an opportunity to shake out procedures for the various command models.

Endnotes

1. United States Marine Corps (29 March 2019) “Marine Corps Operations, MCDP 1-0.” https://bit.ly/3zfPAEE.

2. Bennett, B. (2011). Effective Emergency Management: A Closer Look at the Incident Command System. Professional Safety, 56(11), 28-37. https://bit.ly/3aIBu4J.

NICHOLAS F. NANNA is a 44-year volunteer fire service veteran and the chief of the Dumfries Triangle Volunteer Fire Department in Triangle, Virginia. He is also a retired United States Marine Corps colonel, a CFO, and a former member of the Mount Vernon (NY) and Danbury (CT) volunteer fire departments. Nanna is currently a doctoral candidate in public administration.