By Steven C. Hamilton and Frank Ricci

The disposition of any fire service interaction with law enforcement often depends on training, relationships, and a clear understanding of the interests of those involved. Most fire and law enforcement departments need to reevaluate their training and interagency cooperation. Numerous departments have found that adjusting their response protocol not only is a good idea but is virtually required. Cooperating, not competing, is not just a courtesy anymore—it is a necessity.

Over the past decade, the complexity of the incidents that we have faced—mass shootings, protests, and significant fires—are increasing. Although it is impossible to prevent all horrific events, we must be prepared to respond together to whatever hazards we will face.

The key to success in response is the agencies’ ability to work together well. There’s a lot of talk but not enough communication between agencies. We want to start a dialog and encourage training opportunities among fire and police agencies. Share this article with your local law enforcement agencies to initiate a better working relationship that will allow you to meet your common objectives and serve those you protect.

Roles and Responsibilities

To work well with another agency, you must understand what that agency does and how it does it. The friendly competition over several decades between law enforcement and the fire service has been, in some instances, not so friendly, resulting in disagreements; verbal altercations; and, in extreme situations, arrests. Those incidents have been rooted in the respective agencies’ not understanding each other’s basic roles and responsibilities.

Law enforcement officers are expected to respond to a scene with sensitivity and, if needed, lethal force, handcuffs, Tasers®, pepper spray, and the ability to take your freedom away. A Federal Bureau of Investigation agent once said, “The police exist not to protect the public but to prevent vigilantism.” Although most law enforcement responses have an exigent phase that ends extremely quickly compared to that of fire scenes, the consequences of a law enforcement response can last for years.

The ramifications of a single traffic stop can cause ripples within the justice system and have lasting effects, which can result in court precedents that affect our nation’s laws or may cause substantial social unrest. This puts a great deal of pressure on your local law enforcement officers. Remember, even when called to help, police officers are often perceived as the bad guys, and any interaction they have could result in someone attempting to harm them. Remember this when working with law enforcement.

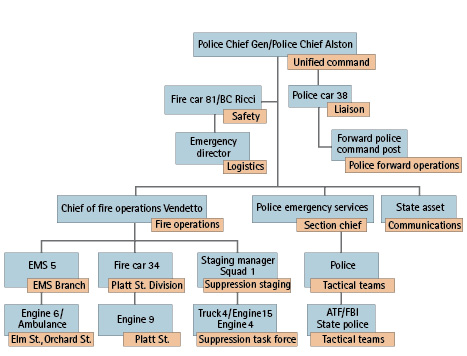

Figure 1. The Joint Operation Incident Command System

Police and fire incidents require expanding the incident command system (ICS). Fire officers use ICS regularly, and it can be an invaluable resource for our police command staff to maintain span of control. (Figure courtesy of Frank Ricci.)

Before the Response

How well do your agencies work with one another? Do you know the first names of the responders in your areas of responsibility? This should be addressed first. For whatever reason, the police station and the fire station in many areas seem to have an invisible barrier that keeps them from visiting each other. For some departments, this is not true, and it is great that the agencies have that kind of relationship. For others, this invisible barrier is counterproductive and transfers to the emergency scene.

Law Enforcement

If you are a law enforcement officer, while on patrol, swing by the fire station from time to time to visit. The station is a safe place to write a report or use the restroom. Keep in mind that you’re the one with the gun. Get out of your car and cross that awkward divide and introduce yourself. Get to know the firefighters in your area, just as you would introduce yourself to business owners and residents. Let them know that this is your patrol area and that you are there to help when needed. Expect firefighters to ask what you, as a police officer, expect from them on a shooting or a domestic incident with a medical patient. It is best to correct misinformation before an emergency.

Firefighters

Firefighters should reciprocate and invite officers on patrol to eat meals with them when cooking for the shift. The firehouse kitchen table has been the foundation for relationship building since the dawn of the fire service; extend that to your law enforcement brothers and sisters.

When law enforcement officers interact with the fire department away from the emergency scene, ask them questions. Pose “what if” scenarios to understand their needs. A good example: “At a barricaded subject response, what does law enforcement need and expect from the fire department?”

Radio Communications

Police. Can fire and police personnel monitor or even communicate with each other using the radio? If police and fire are unable to monitor each other’s radio channels, that is a problem. Make cross-communication a reality sooner rather than later. In the meantime, ensure that police know to advise dispatch whether and where fire apparatus should stage and, after any threats have been neutralized, when it can safely enter the scene.

Knowing where units are staging is important to law enforcement. If the scene is active or the suspected assailant is mobile, knowing that the individual fled in the direction of the staged units could prove to be important information.

(1) A bomb squad dog clears the fire department staging area at a civil protest. (Photo courtesy of Frank Ricci.)

At emergency scenes at which the fire officer is requesting law enforcement, the responding police officer should ask dispatch some basic questions. Is the request for an emergent response? What exactly is needed? On which radio channel is fire operating?

Once, as I (Hamilton) was on duty as a sheriff’s deputy, I heard a radio request from fire personnel for law enforcement response to an emergency scene outside of my patrol zone. That was all the dispatcher had relayed. I switched over to the fire department operations channel and heard fire units reporting that an individual was being violent at a vehicle accident. I notified the responding deputy to step up his response and request a backup unit after explaining the situation in more detail. Had I not switched over and monitored the fire channel, it might have escalated into a serious incident. It is extremely important to seek more information if dispatch does not provide it. Law enforcement officers should have a pretty clear picture of what they are responding to when requested by emergency units already on the scene.

Fire. Fire departments may have some set procedures of when law enforcement needs to respond in support of fire operations. They include forcible entry, evacuation, and shelter-in-place operations; medical emergencies involving the discovery of weapons; and suicide attempts. It is important to communicate in advance of these incidents. Law enforcement personnel should ask how the fire department would like them to respond—emergent or nonemergent?

On several calls in which fire personnel have been forcing entry, they have requested law enforcement response. In most cases, this should be an emergent response. I have heard several radio calls where law enforcement has refused to respond, thinking that fire wanted law enforcement to perform the forcible entry. This is a prime example of miscommunication before the response. Fire personnel are requesting law enforcement because they are legally breaking into a building, usually a residence. Law enforcement must be there to ensure the safety of fire personnel and the security of personal property. In several incidents, residents have assaulted firefighters, thinking they were burglars breaking into their homes.

If we communicate before the response, we can avoid such scenarios and strengthen the fire service/law enforcement relationship. The emergency scene is not the ideal place to make an introduction. Take the extra step to meet one another in advance and communicate expectations and needs well before meeting at the scene.

Medical Issues

This area has numerous overlaps in jurisdictions and authority. A shooting is a crime scene, but after scene safety, patient treatment must be the next priority, followed by a concerted effort to avoid contaminating a crime scene. In your jurisdiction, what agency is responsible for determining death? If it is the fire department after consulting medical control, then the police need to be fully aware of this.

In an assault, has the victim who may have been the assailant been frisked by the police? Don’t assume that the victim has been cleared just because there are several police officers on scene. If you feel the situation warrants searching the victim, ask the police officer.

At medical emergencies, it is important for law enforcement to stay engaged in what is occurring on the scene. Although paramedics and emergency medical technicians (EMTs) may be on the scene and tending to patients, law enforcement is still needed. On more than one occasion I (Hamilton) have had to ask law enforcement to engage or even had to leave the scene and get law enforcement to come back into the house for a violent patient.

Police officers should stay at the scene; if the situation is escalating, they should ask if their assistance is needed. Paramedics and EMTs may say no at the time, but five minutes later, they could desperately need assistance.

Also note that while there is an epidemic of narcotic overdoses across the country, law enforcement officers are not medical providers. EMTs, paramedics, and law enforcement personnel are being supplied with quick-response overdose medications. Several anti-narcotic medications can cause the patient to react violently.

In New Haven, Connecticut, the fire union fought and prevailed on not issuing the police Narcan®. Medical protocols from Yale Hospital dictate that after Narcan is administered, the rescuer must be prepared to rescue-breathe for the patient. An officer must use both hands to assist in rescue breathing, which leaves the firearm exposed. Police officers are equipped with several weapons of which the patient or bystanders may attempt to gain control. Officers must be extremely cautious in these situations and know exactly when to deploy anti-narcotics and the results to expect from such actions.

Closing the Road

The authority to shut down a road may rest with the fire department in some municipalities or with law enforcement in others. Know the laws governing road closures in your area and communicate your agency’s needs at an incident. If the state authorizes law enforcement to shut down a road and a fire department does so without communicating the need to the police properly, it can result in problems between agencies. Likewise, the fire department closing a road because it has the legal right to do so without communicating can also result in problems. Just because you have the right doesn’t absolve you from the responsibility of communicating your actions in advance and developing a multi-agency plan. Has your department communicated your policy of always blocking the lane in which the accident occurred and closing one extra lane to provide a safe working area? Have your chiefs or training directors shared your standard operating procedures (SOPs) that require a multiagency response with law enforcement? This is also a way to open a dialog of roles and responsibilities pertaining to the roadways.

Fire Scene

At fire scenes, do not assume that what is obvious to your department is equally obvious to law enforcement. Fire hydrant locations, apparatus placement, crowd control, scene security, fire behavior, and actions that affect fire behavior all seem like “no brainers” to the fire department, but the well-intentioned, but uninformed, police officer may hamper operations. It is easy to slam the officer for his actions, but first ask, “Did he really intend to screw up the fire operation?”

Police Parking

Police must understand that at every fire, several companies will respond. We have seen the police clear the street to allow the truck company into the street, only to then block the road and leave the police car there, unattended. This has hindered the third- and fourth-due companies from positioning.

The police vehicle’s placement is not dictated by the first engine’s location. This apparatus is usually dropping off crew members or hooking up a hydrant so it can drive up just past the fire building (a forward lay). In a reverse lay, the engine stops at the fire building, drops off firefighters, and drives to the hydrant. Other times, the second engine on scene will lay a supply hoseline from the first engine to the hydrant.

Note that a ladder company will demand the front position at the structure. We can stretch hose, but we cannot stretch a ladder. If a police officer is assigned to block a road, that officer must stay with his car. Fire personnel and apparatus will arrive at various points during the incident and will need access. Police should not park in front of the building, where the vehicle will hinder fire operations. Police should prepare to shut down the nearest intersections to ensure fire hose is not driven over. It would be best if police officers reported to command or a fire officer prior to posting at a traffic control point. When in doubt, they can communicate by radio to fire personnel on the scene directly or through dispatch.

Police Good Intentions

Police officers at times will arrive at a fire and attempt to perform a rescue before the fire department arrives. Acting without a full understanding of fire behavior, they will endanger themselves and enable the fire to grab hold of the building, endangering occupants and causing significant property loss. Fire creates high pressure and will always move to low pressure. Superheated air will move away from the fire across the ceiling. At the same time, cool air will move toward the fire along the ground. These two directional forces meet at the neutral plane. The lower this plane gets to the floor, the more dangerous the situation becomes. The cool air that runs toward the fire feeds the fire oxygen and allows the fire to grow exponentially.

We have all been to fires where a well-intentioned police officer has left the front door or apartment door open, allowing the fire to gain control of the public hall or stairwell, trapping or endangering other occupants. When a police officer arrives on the scene of a fire ahead of fire units and after ensuring his vehicle is out of the way of apparatus, he can make a positive impact by closing the door. This will deny the fire energy. Likewise, it is always a bad idea for a police officer to break windows.

As Deputy Chief (Ret.) Anthony Avillo, North Hudson (NJ) Regional Fire & Rescue, says, “No one is tougher than a fire.” You cannot talk your way out of this one. Without breathing apparatus, the smoke is toxic, blinding, and hot. This is not the campfire you may know; it is smoke that will choke you and drop you in seconds. New York Police Department Officer Dennis Guerra, 38, lost his life while attempting to get occupants out of a high-rise. We should not forget his bravery, but we must learn from this tragedy.

Fire Department Parking at Police Incidents

There are opinions on this. For a volatile, potentially violent situation that could lead to civil unrest, stage at an intersection so you can reposition if the incident escalates. For a response to an assault with the police already on scene, position the apparatus past the house to allow room for the ambulance. On a bomb threat call, if you have had an alarm in the same location before, do not stage at the same hydrant. Someone with nefarious intent may be monitoring your positioning for a secondary device placement.

Command for Fire Incidents

Very few fire department emergency responses do not garner the attention and response of law enforcement officers. At most of these incidents, the actions of law enforcement personnel are not just needed, but they are appreciated. However, there are times that police response can make the fire department’s job harder, which is directly caused by miscommunication.

Fire departments have championed the incident command system (ICS), which can be foreign territory for the police. The fire department must insist that, on arrival, a law enforcement representative (one not assigned to traffic control) must report to incident command to see what police assistance is needed and to notify the fire department of police needs. The fire department must do this without exception.

At the incident scene, fire personnel can easily identify the command post, but law enforcement may not. Often, the police approach the first firefighter they see and ask what police need to do. Firefighters should direct law enforcement to the command post or to a company officer. For police officers, seek out a fire officer. Law enforcement needs to understand how the rank of firefighters is distinguished when in bunker gear. Fire departments have several helmet schemes that differentiate fire officers from firefighters. The time to learn which one is the fire officer is not when on the fireground.

Further, many departments have been using a green light on the apparatus to designate it as the command vehicle. Dispatch should also update the police department of the fire command post’s location once it is announced. Seek out that green-light vehicle or the command post and ask for the incident commander (IC). Ideally, a police officer should check in with fire command for an assignment, not just self-assign to a task. If law enforcement personnel have access to the fire department’s nontactical channel and vice versa, they can request assignments that way. However, the police still need to have a representative report to the command post.

Command at Police Incidents

It is a good practice to set up a fire department command post at police incidents and ask for a law enforcement representative. For example, at a call for a suspicious package, the fire department should be prepared to set up emergency decontamination if an officer is going to be dressed out or go down range with a bomb dog. The bomb dog should always clear the command post first before moving down range (photo 1). The police representative should have command authority and be able to monitor tactical and operational radio channels. Fire department personnel can assist the police with accountability and checking and tracking resourses at the scene (Figure 1).

Active Shooter, Barricade Situations

The proverbial “elephant in the room” is active shooter response. Should the fire department and emergency medical services (EMS) agencies embed themselves into law enforcement operations to save casualties or wait for the scene to be declared “clear”? Even now, many departments are tackling this question and its inherent consequences. Do departments buy and equip personnel with body armor? If so, what level of protection is appropriate? These questions necessitate a great deal of consideration before reaching appropriate answers. A bulletproof vest is not a failsafe. Firefighters often think that a vest is going to protect them from every situation—this is not true. One live round will tear straight through the common vest most patrol officers wear, and a vest provides no protection for a shot to the head or face.1 Consult your law enforcement partners. The police ultimately determine the role the fire department will have at these events. The scene either has or has had a direct hostile threat, the quelling of which is a law enforcement function. Each agency has a vested interest at these incidents, but law enforcement holds the key for entry and coordination. Preparing with one another in advance of these incidents is paramount for a successful response (photo 2).

(2) For active shooter incidents like at the Pulse nightclub, the public expects the emergency service response to be coordinated, professional, and effective. (Photo by Steven C. Hamilton.)

Hot Zone

Fire and police should adopt the same terminology for protective zones. Following the hazardous material model, designate the area in which the shooter is believed to be as the hot zone, whether it is a building, a floor, a house, nearby woods, or a vehicle. The hot zone is a direct threat area in which individuals or devices pose an extreme risk of severe bodily injury or death if contact is made or the device detonates. Law enforcement will deploy officers into this area to locate and stop the human threat or to locate and identify improvised explosive devices (IEDs) as well as improvised incendiary devices (IIDs). These officers are known as contact teams and mostly likely will be road patrol personnel and not a specialized weapons and tactics team.

Warm Zone

The warm zone is an indirect threat area in which threats are not believed to be, or it is an area in a line-of-sight from the hot zone in which the perpetrator can direct fire on first responders. However, law enforcement cannot guarantee there is not a threat. To “clear” an area, law enforcement must sweep it and check every space that could pose a threat. In large buildings and open spaces, this could take hours and dozens of law enforcement personnel. This is at the heart of the question of whether fire and EMS personnel can wait for that process to be completed. Some believe that waiting will cost lives and that fire and EMS should work in the warm zone to reduce the loss of life.

Regardless, personnel who work in this area need a level of safety to operate effectively. Ballistic protection affords a level, but it is not without flaws. There should be layers of police security for personnel working in the warm zone, with or without body armor. For example, in protected corridors, several law enforcement officers line a hallway with weapons drawn and ready to engage a threat if it appears. This is well after the initial reported threat has been stopped and is a layer of protection for secondary threats.

Another example is the rescue task force (RTF), which enters warm zones with headlight and taillight security—i.e., law enforcement officers are embedded with fire/EMS personnel. The RTF moves collectively as a team to reach casualties to identify, treat, and extract viable patients. If fire/EMS personnel intend to operate in the warm zone, they must consult local law enforcement and provide ballistic protection for their personnel well in advance of an incident. Entering a warm zone without the proper ballistic protection should be the exception and not the rule. The end of this area can be marked with red fire line tape.

Cold Zone

The cold zone is a no-threat area—there is no risk of aggressors, direct fire, IEDs, or IIDs. It is typically where the command post and level I or II staging are and can also be where command establishes a casualty collection point (CCP). Be sure to establish a transportation corridor for ambulances to enter and exit the scene. An incident scene may have multiple CCPs and should not be confused with a sift-and-sort (initial triage) area, which is typically in the warm zone. Casualties are moved to sift-and-sort areas before being extracted to the CCP. Commonly initiated by law enforcement, first-line triage is performed here. Further, the cold zone is where the medical group performs the bulk of their duties to include treatment and transportation officer functions. In an incident in which fire is used as a weapon, fire department personnel may connect to the fire department connections (FDCs) or sprinkler connections in the cold or warm zone as well. The cold zone must be enclosed with yellow tape.

The Fourth Zone

A fourth, as yet unnamed, zone is being discussed now. It contains secondary or ancillary functions that do not directly involve the incident operations. Vehicle accidents, traffic problems, casualty reunification areas, media areas, and the like all fall into this zone. Arguably, these are all secondary concerns of the main incident location; however, they necessitate a full set of resources independent from those involved with the primary incident location, including command and control functions. The IC must focus his attention on the responders and the incident objectives where casualties are present. Distractions from secondary issues will affect the primary incident action plan.

Fire and EMS also must understand that the zone concept is fluid and can change with little to no notice. Active shooters may go “mobile” and move throughout an incident scene or structure, expanding or contracting the hot zone. Additionally, responders may find devices at any time during an incident, and so a cold zone may become a hot zone quickly. The San Bernardino, California, active shooters drove around their initial attack area attempting to detonate an IED that they had placed during their attack. The device never activated and was not initially found by entry teams until later in the incident. Had it detonated, several responders as well as already injured casualties would have been wounded or killed.

Identify the zones in some fashion, and communicate them to all personnel working at the incident. You can use scene tape to identify the zones, but if they change because of the threats encountered, it may cause confusion. Use easily communicated features until tape, cones, or other visual markers are in place.

For example, the side A parking lot is the cold zone, and the front entrance foyer is the warm zone (photo 3). Zone identification and zone changes should be communicated and acknowledged by division, group, and task supervisors when established and if changed.

Finally, multiple zones may exist on the same incident scene. As we recently saw in Las Vegas, a shooter on an upper floor creates multiple hot zones. The floor on which the shooter is is a hot zone as is the area on the ground within the gunsight and shooting distance of the aggressor. This could be the sixth floor of a hospital and the parking lot below. Remember that fire and EMS personnel should not operate in the hot zone, so that hospital parking lot should not have any fire or EMS assets in or around that area.

(3) On the B side of the Pulse nightclub, the shooter had fired rounds that penetrated the exterior wall and traveled outside. The SWAT team conducted an explosive breach here. Based on the threat of serious injury or death, the area outside of the B side would be a hot zone. (Photo by Steven C. Hamilton.)

Predetermined Assignments

The fire department is used to having an assigned tactical channel and predetermined responder responsibilities based on a fire company’s order of arrival at an incident. The police department’s tactical or special operations teams may not have the same predetermined coordination.

For example, in some cities, the city special weapons and tactics (SWAT); the Bureau of Alcohol Tobacco Firearms, and Explosives (ATF); the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI); and the state police all want to get in the game. It makes sense to coordinate the response according to arrival on scene. A good example of predetermined tactical team assignments could be the following: The city team has the task of stopping the threat, the second team is assigned victim removal to EMS, and the third team is assigned force protection (surrounding the perimeter with a show of an armed force). This can all be altered based on the circumstances. However, it allows the police IC a template for an incident action plan that can be adjusted as needed.

The fire department should also realize that, depending on the circumstances, it may have to establish a medical group or branch and a suppression branch or fire/rescue group within the ICS. Stage a structural fire response with a staging manager in case the structure is light on fire and the threat is reduced. The fire/rescue department has many responsibilities in addition to casualty extraction. Fire as a weapon is a real threat that may require fire department personnel to aid in extinguishment or control of a fire intentionally set by aggressors or unintentionally by devices deployed by law enforcement such as flash bangs and tear gas devices.

Notify fire personnel that police tactical teams will be making entry, but do not announce it on a radio. A way to communicate this without a code is to have staged fire department assets switch to a tactical radio channel for operation. This will signal to get ready for possible patients and a fire response if an explosion or a fire is reported.

Preplanning

A suggested path forward is to conduct preincident planning from a multiagency perspective. Fire, EMS, and law enforcement with facility staff need to walk through high-risk occupancies in their jurisdiction as a team and conduct preincident hostile event planning. Gathered information should include the following: facility construction, utility locations, HVAC controls, elevator operation, crawl spaces, door and lock construction, types of windows and their glass makeup, uncontrolled and controlled access points, exterior footprints such as parking lots and landscaping, and cover and concealment points. The list can be endless, so all agencies that have a vested stake in the response must conduct the preplan together.

Law enforcement special tactical teams will want to know information that the fire department never thought of and vice versa. This single walk-through of the mall or the courthouse will be extremely valuable, not just for a response to that facility but also toward understanding each agency’s thought processes, incident objectives, and priorities. This opens opportunities for training. For example, a discussion of door and lock construction could lead into forcible entry techniques about which partners may want to know and see more.

It is not possible to expand into great detail as each jurisdiction’s threats as well as response postures are vastly different. Most of the policies and protocols that can be found focus on the larger municipalities and where there exists an extreme desire for aggressors to conduct attacks. That said, there have been multiple incidents in smalltown American where resources are scarce. The most important aspect to glean from this section on active shooters is to engage your partners and discuss what threats your jurisdiction may face as well as develop a plan to discuss those threats further with a joint response posture in mind.

The pathway to a cohesive response to an active shooter incident locally begins with the points in the beginning of this article. Personnel need to know one another and work well with each other at the task and tactical levels well ahead of such an incident. There are national level efforts being achieved as well. The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) is drafting NFPA 3000, Standard for Preparedness and Response to Active Shooter and/or Hostile Events. The committee is comprised of experts from the fire service, EMS, and law enforcement, among others. This is one of the largest gatherings of multidiscipline emergency responders for guidance development ever assembled for active shooter response. The outcome will help set the groundwork for agencies to plan, prepare, and respond to these types of incidents. If this can be accomplished nationally, it can also be accomplished locally. It may just take an introduction and a handshake.

After the Response

The fire department spends a great deal of time reviewing and critiquing its actions at emergency scenes for lessons learned. Law enforcement officers are not often included in that process. When conducting critiques, hot washes, or after-action reviews, ensure that you invite the responding law enforcement officers. For law enforcement, seek a seat at the after-action review when appropriate. If a formal process is not in place, ask for such a discussion. When lessons can be learned, share them with other shifts. We must not continue to make the same mistakes over and over again. There is little excuse for a mishap to occur on a different shift if it had already occurred on a previous one.

Identify issues and express needs when they are known. Personnel need to resist the urge to “trash talk” an individual or agency for its response after the fact. It is better to address the shortfall and ensure that it does not happen again. Often, the mishap or mistake stems from a communication issue or misunderstanding of expectations. A simple conversation followed up with documentation that can be shared among other responders will ensure a better response next time.

Reference

Hamilton, Steven. C. “Selection and Use of Ballistic Protection for Fire and EMS Personnel.” (June 2015) Fire Engineering, 53-58. http://emberly.fireengineering.com/articles/print/volume-168/issue-6/features/selection-and-use-of-ballistic-protection-for-fire-and-ems-personnel.html.

STEVEN C. HAMILTON has been a member of the fire service since 1996. He is a lieutenant with the Fort Jackson (SC) Fire Department and a senior reserve deputy with the Richland County Sheriff’s Department. Hamilton is a certified fire officer III, an instructor III, an arson investigator, an emergency medical technician (EMT), and an EMT instructor. He served in the United States Air Force for four years and has been a volunteer with fire departments in South Carolina, Texas, and New York. Hamilton is the presenter of the “Responding to Scenes of Violence” DVD (Fire Engineering, 2015), and an FDIC educational advisory board member.

FRANK RICCI is a member of the educational advisory board for Fire Engineering and FDIC International. He is a battalion chief and the drillmaster for the New Haven (CT) Fire Department. Ricci is also co-host of the BlogTalkRadio radio show “Politics & Tactics.” He is a contributing author to Fire Engineering’s Handbook for Firefighter I and II and the lead author for the Tactical Perspectives DVD series. Ricci has been the lead consultant for several Yale studies and a past student live-in at Station ٣١ in Rockville, Maryland. He won a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case regarding fire service promotions.

RELATED

Why Stage for Law Enforcement?

Tips for Working with Law Enforcement

Firefighter Involvement in Law Enforcement Activities

Fire/EMS at Active-Shooter Incidents

PRESERVING THE FIRE SCENE: TIPS FROM LAW ENFORCEMENT

The Scene Is Not Safe: Protecting Your Responders