By Christopher B. Carver

Over the past year, fire departments across the United States have responded to such large-scale disasters such as tornadoes, floods, hurricanes, and blizzards that are often perceived to be “once-in-a-lifetime” tests of local response capabilities. The number and severity of tornadoes during 2011, for example, was the worst in decades. These types of incidents, although devastating in scale and scope, may become even more frequent challenges to emergency response agencies as severe weather phenomena increase in frequency.

Fortunately, these large-scale disaster events, although a significant test of a department’s response capability, do not have to be impossible to manage. Through efforts in planning, training, leadership, empowerment, and decision making, all but the most incredible disasters may be managed in way that either facilitates effective response until outside resources arrive or maintains management locally using local resources.

PLANNING AHEAD

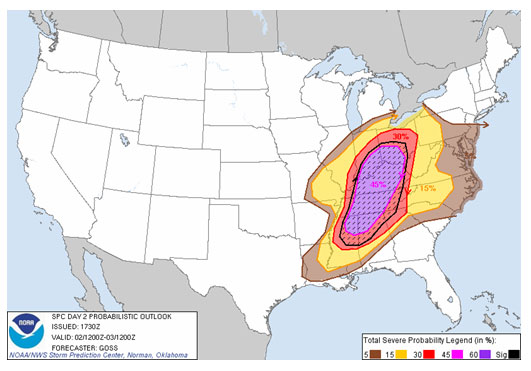

The first key to a successful response to tornadoes and other severe storms is the fact that these events are rarely a total surprise. Prediction information is available, so agencies can realistically plan ahead. The National Weather Service and its weather-specific sections such as the Severe Storms Prediction Center (SPC) and the National Hurricane Center are excellent resources when your agency faces severe weather and they often provide significant lead times for major threats. Any chief or officer in an area that is prone to or has a significant possibility of storms should view the Storm Prediction Center’s convective outlook page (http://www.spc.noaa.gov/products/outlook) at the start of every shift. This page and the associated SPC homepage (http://www.spc.noaa.gov/) provide a detailed report on the likelihood of severe weather (e.g., thunderstorms, tornadoes, wind, and hail) with associated risk factors (i.e., slight, moderate, or high for the current day) in great detail and a progressively more generalized outlook for upcoming days–up to one week ahead. If you’re in a high-risk or storm-prone area, implement a predetermined plan for such weather. You should also have related plans for hurricane preparation and response; information is for this is available on the National Hurricane Center’s Web site at (http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/).

(1) Storm Prediction Center Outlook Page for recent severe weather event (one day prior)—highlighting high risk areas and providing significant lead time to have resources in place.

Once an area has been identified as being at risk, any plan that is initiated (and developed, preferably well in advance of your area’s primary threat period) should focus on increasing resources, which includes two key efforts: increasing the number of apparatus on the street and increasing the number of personnel on apparatus, or both. One potentially significant way to increase resources is for departments to deploy utility units to manage low-priority calls during storms–thereby preserving mainline apparatus (engines, ladders, rescues) for high-priority calls. It makes little sense for departments to heavily staff apparatus in a storm only to have that heavily staffed engine sit for hours on a wire-down call awaiting the power company while mutual-aid units respond to a structure fire down the street.

Many departments will avoid bringing in resources, confident that mutual aid will be available–this is a shortsighted approach and one of the most frequent failed assumptions about storm-response management. The same storm that impacted one agency likely impacted the agencies in the surrounding area. Assuming that a neighbor will be able to commit resources to your fire is a potentially dangerous assumption. Any mutual aid that would be available may have to come from much farther away than normal–one reason why a regional approach to storm response management is clearly the best approach.

Beyond staffing several utility response units for lower priority emergencies and enhancing staffing on rescue and ladder companies (who would likely be the most “in-demand” apparatus after a storm), another effective approach is to limit the number of resources responding to all incidents. Fire alarms, odors of gas, smell of smoke, or other types of incidents should receive the minimum safe response during and immediately after a disaster. Conserving resources in this way preserves their availability for structure fires or major rescue incidents, should they occur. During storm periods, you could send a reduced response for single calls reporting a fire, but receiving multiple calls for a fire should mandate the full structure fire response required–which may be fewer units than normal, if your department is more heavily staffing fire apparatus. To ensure this, assign priority levels to all of your department’s call types. Although normally you may send units in a first-in, first-out manner, adopting an emergency medical dispatch-type priority system for fire incidents will permit effective management of a workload that often spirals out of control during and after a major weather-related disaster. Another component of this type of resource management would be to provide an extra person to your emergency medical service (EMS) units–eliminating the need to send fire suppression units to back up the ambulances, except in extreme cases.

MANAGING RESOURCES

The key to ensuring the effective operation of any storm plan will be dispatch personnel and supervisors. The importance of these personnel in the day-to-day resource management of a fire department–and especially in a storm-response environment–cannot be overstated. However, their ability to be resource managers is often an overlooked skill. Many departments prefer to consolidate responsibility for modifying responses, duplicating calls (deciding one call is the same as another), and relocating resources (move-ups) at the chief level. Few things demonstrate that dispatchers are an underused or underappreciated resource as the battalion chief, while is commanding a fire, also determining who should move from where to ensure fire protection in an area. Frankly, if dispatchers are not deemed capable of performing these tasks, then they are not being trained to their potential or the department does not wholly view their dispatchers as resource managers. Especially during a stormwith potentially hundreds of calls for service, a severe depletion of resources; and many other demands–a chief should not have to worry about being the resource manager for an entire jurisdiction Chief officers simply cannot know all of the ongoing elements of the disaster or a complete picture of the event unless they are actually in the communications center or emergency operations center. Dispatchers should be empowered to make decisions, enact the plan, redirect units from lower- to higher-priority incidents, hold minor calls, and coordinate the response of distant units for relocation or operation at incidents as necessary and within the framework of an established plan. If your department or agency is unwilling to give dispatch personnel this type of authority, another solution during storm emergencies would be assigning an officer or chief to the communications center to address resource-management issues, relieving officers and chiefs in the field of this responsibility.

An additional, and equally important key is that all personnel–dispatchers, company officers, and chiefs–must be prepared and encouraged to think “above their pay-grade” during large-scale disasters. Even the most well-written plan may not anticipate every outcome or every possibility. The disaster may feature several compounding elements–the chief in charge of enacting the plan may be out of town, or the communications system may fail. The measure of success is not whether you followed the plan to the letter, but whether you managed the disaster’s initial phase or “golden hour” effectively. This will either buy time for significant outside resources to arrive or it will allow local resources to handle the incident and save precious resources such as urban search & rescue teams to be deployed where they may truly be needed.

THE NEED TO TRAIN

Besides empowerment, training is an additional critical foundation of a successful disaster response plan–training for every dispatcher, every firefighter, every paramedic, and every chief. Once they are completely versed on the weather threats posed to the area your agency protects and your department’s planned response to these events, your personnel can operate more confidently and more effectively when “the big one” strikes. This doesn’t mean you have to write a detailed plan covering everything down to the room temperature of the emergency operations center. Use common sense and create a high-level guide to the actions that the department should take automatically when the threat of severe weather exists. This plan should fit on no more than one sheet of paper–not including possible appendixes by threat type with specific action plans, such as personnel actions during a hurricane. To avoid the problem of “one person in charge,” the plan’s activation should be triggered by events, not by people. For example: “When a severe thunderstorm watch is issued, we will go to staffing level B.” This absolves individuals of the responsibility to make critical decisions or waver about them.

The public, if possible, should be included in the disaster plan information process. Disaster preparation tools for a local population should include reminders that 911 should only be used for emergencies–especially during disasters and that nonemergency complaints, such as water leaks, fallen branches, or similar events should be relayed to your local governmental information hotline (if applicable) or some other nonemergency contact point. This will lessen the burden on dispatchers and responders.

Finally, there must be a change in mindset among certain organizations that view being proactive as a bad thing, or that failing prepare when the storm isn’t as bad as you thought indicates great leadership. In this time of diminished resources and tight budgets but ever-increasing demands for service, knowing in advance when some of our busiest days will likely be is a great advantage, one that should be used whenever possible. If the storm misses you but not the next town, you will have extra resources to provide aid immediately to your neighbor. If an even better outcome occurs and there is no storm damage anywhere, see that as a training day in which personnel became more comfortable and familiar with recall and response procedures. When “the big one” does hit, they will be ready.

Finally, if you have information that your jurisdiction is under threat from severe thunderstorms, high winds, tornadoes, and so forth, and you don‘t take steps to prepare effectively, think of what could occur if one strikes your response area. Although the phrase “Act of God” may work for some insurance companies, it’s a terrible defense for your agency if it is overwhelmed by the initial stages of a disaster and didn’t have to be. The public has come to expect more from its public safety professionals–and we should expect more from ourselves.

CHRISTOPHER B. CARVER is a 17-year public safety communications veteran and a chief fire dispatcher with the Fire Department of New York. He is an adjunct professor at John Jay College in New York City and a writer and consultant on fire service communications issues. He resides in Brooklyn, New York.