(1) In this undated insurer photo taken from the southeast vantage, the West Fertilizer Plant is seen during a regular day of operations. The seed room, where the fire is believed to have initiated, can be seen in the right of the photo. (Photos courtesy of the Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office.) (1) In this undated insurer photo taken from the southeast vantage, the West Fertilizer Plant is seen during a regular day of operations. The seed room, where the fire is believed to have initiated, can be seen in the right of the photo. (Photos courtesy of the Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office.) |

By Brian A. Crawford

On April 17, 2014, I sat quietly in a small church in West, Texas, reviewing my notes to a PowerPoint® presentation that was about to be delivered. There was really nothing to review. As one of the authors, I knew the contents of the pages before me all too well. I was just trying to work off some nervous energy. My real thoughts were focused on how many people would show up and, more importantly, how a sensitive portion of the program, “Findings and Recommendations,” would be received. As the restricted and invitation-only crowd of surviving family members, local firefighters, and a few media reporters filed past security, one by one they made their way down the aisles and settled into scattered rows of padded back pews. As the clock struck 6:00 p.m., the members of the Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office West Firefighter Fatality Task Force took a collective breath and presented its findings and the story of West.

One year earlier to the date of the presentation, a long-standing fertilizer mixing and distribution facility, located on the eastern edges of the town, exploded, leaving 15 dead and hundreds injured. Ten firefighters were among the dead. The actions of the local firefighters who responded to the call were not unlike those seen hundreds of times by residents in the past when dealing with ordinary structure fires. However, this day, the firefighters of West were not dealing with a simple structure fire. They were dealing with a very complex commercial chemical fire with a potential for deadly results that were unknown to or underestimated by the initial responding crews. One thing is certain, however: No one in the small, sleepy Texas community could have imagined that by nightfall the town would be the center of worldwide attention and the site of an event that caused one of the largest losses of firefighters’ lives since 9/11.

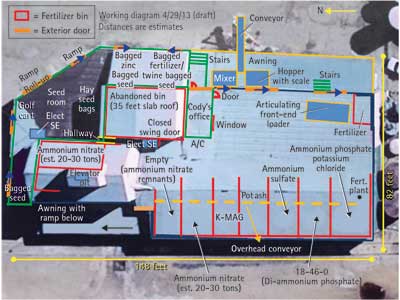

| Figure 1. Schematic of the West Fertilizer Plant |

|

| Figure 1. This schematic was developed by the investigative teams to demonstrate the layout of the facility as well as the location of hazardous materials stored on site. Note the estimated 20 to 30 tons of ammonium nitrate stored just below the seed room where the detonation is believed to have occurred. |

The city of West is in McLennan County in the heart of north-central Texas. The West Volunteer Fire Department (WVFD) is an ISO Class 5 agency made up of hardworking and dedicated community volunteers. In the previous year, the department responded to 73 fire-related calls, 18 of them structure fires. The city’s water system is made up of 12-inch arterial mains stretching from the city of Waco to a pump station just south of the town. The interior of the city is covered with eight-inch mains that normally provide 48 to 50 pounds per square inch (psi), but on the day of the incident, the psi available was below 20 because of a damaged line.

That evening, just prior to the incident, three West volunteers were grabbing a bite to eat at the local Exxon station when the page came in for a fire at the West Fertilizer Plant. A police officer was driving by a local basketball hangout close to the plant when he first noticed the smell of smoke and one of the kids playing ball said, “Smoke is coming from the tall building of the fertilizer plant.” At that point (about 7:32 p.m.), Officer Michael Irving contacted McLennan County Office dispatch and reported: “Kick out West Fire. One of the mills at the West Fertilizer Plant is on fire; heavy smoke is coming out of the roof.”1

|

| (2) One of the earliest photos of the fire, taken from the southeast side of the plant, showing one of the first unidentified firefighters on scene. |

One of the individuals at the Exxon station was Firefighter Cody Dragoo, who headed straight to the fire scene; the other two firefighters went to retrieve a pumper from their lone station. Dragoo was all too familiar with the location of the call. Along with his volunteer firefighting duties, he was also the assistant plant manager for the West Fertilizer Company. By the time he arrived, the northeast portion of the building was heavily involved in fire and billowing black smoke.

Initial Actions and Explosion

As the first engine (Engine 1) pulled up along the east side of the plant at approximately 7:39 p.m., three firefighters began suppression operations with two 1½-inch handlines, focusing on the seed and fertilizer building. The firefighters from Engine 1 began an attack on the interior of the building by directing their hoselines through a roll-away door and into the structure. As other department personnel and resources began to arrive, a permanent water supply became a priority. West’s only other engine, Engine 2, began laying down four-inch hose from a hydrant 1,600 feet away. When Engine 2 dropped its last section of hose from its bed in the middle of a field south of the plant, it was 600 feet short of reaching the fire.

|

| (3) The first-arriving West Volunteer Fire Department crew, Engine 1, set up operations on the east side of the plant. |

As the driver of Engine 2 continued onto the scene, his hosebed empty and the growing and luminous fire still without a water supply, Captain C.J. Gillaspie would end up swapping out his engine for Engine 1. The plan was to reverse lay from the fire back to the distal end of the 1,000 feet of four-inch hose he had just left. However, in the chaos and confusion of the scene, he took Engine 1 all the way back to the original hydrant, past the four-inch hose lying in the field, without ever dropping any new supply line from his just acquired pumper.

As a brush truck and other fire department resources and volunteers, including a group from the West Emergency Medical Services night emergency medical technician class and off-duty Dallas Fire Captain Kenneth Harris arrived at the scene, the fire intensified. Officers along with rank-and-file firefighters spoke about potential strategies for dousing the fire but took no action to reassess the impending dangers that the 40 to 60 tons of ammonium nitrate, a Class 3 unstable reactive detonable (UR3D) and oxidizer, inside the structure presented. Despite the observation of a chief officer on the scene that they “needed to go” and a warning from a former plant employee to the chief that he should get everyone out because “it’s gonna blow,” no order to withdraw was ever given. (1)

|

| (4) This photo was taken from the high school, approximately 1,600 feet southeast of the plant, believed to be just prior to the explosion. |

Then at 7:51 p.m., only 12 minutes after the first company arrived on scene, 10 firefighters were gone. So, too, was the iconic town image of the 12,000-square-foot, multistoried, white, and sheet metal-covered plant that most in the area said had always been there; the town grew up around it. The structure was obliterated in a massive explosion that registered 2.1 on the Richter scale for earthquakes and left a 90-foot-wide and 10-foot-deep crater while sending debris as far as 2.5 miles away. (1)

In the aftermath of the explosion, an estimated 130 public safety agencies and 1,500 volunteers responded to West to provide whatever assistance they could. More than 25 city blocks were affected. More than 120 homes, businesses, and schools were destroyed. Structural damage totaled some $100 million. Gas, water, and electric to the city were completely disabled for indefinite periods of time, making even the unaffected areas of the town uninhabitable.

Investigation

The Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office (TSFMO) was notified of the multiple firefighter fatalities in West the evening of the incident. Based on the authority granted to the agency by the Texas Government Code, the fire marshal immediately began a formal investigation. As is customary, the TSFMO contacted the Texas Fire Chiefs Association (TFCA) to assist the task force in the investigation, specifically to evaluate fireground operations and tactics and to develop a list of findings and recommendations in accordance with best practices and national standards.

|

| (5) The explosion from the vantage of West Volunteer Fire Department’s Engine 1. |

In the early stages of the investigation, the TFCA task force members were partnered with an Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) agent to conduct postevent interviews with surviving firefighters, first responders, and civilians intimately involved in the event. This work began two days following the explosion and involved individuals who clearly were still traumatized and dazed by the totality of their circumstances and the fate of their fellow firefighters.

Those with whom I spoke were open, honest, and still trying to come to terms with exactly what had happened. Their candor and willingness to cooperate enabled us to glean critical information that helped us create a comprehensive blueprint of what happened. They, too, wanted to provide whatever material facts they could to ensure that all understood the full extent of their actions in doing whatever was necessary to protect their small community and to share their experiences so future incidents of this nature could be prevented.

It became readily apparent following the first day of interviews that the WVFD was well rehearsed in combating simple Type V-B (unprotected wood-frame construction), common to most of the single-family homes in the community. However, they were not prepared for a fire incident of the complexity and magnitude of the one they faced on April 17, 2013.

|

| (6) The explosive cloud could be seen for several miles in every direction, prompting a large number of first responders to self-dispatch to the scene. |

The final report tells of a fire department with striking heart and determination to protect its community at all costs, but one that was completely overwhelmed by the distinguishably different set of circumstances and multifaceted challenges of what they faced in contrast to their regular and routine fire suppression activities of the past. Those sentiments were echoed and punctuated in the document’s following statements.

• The lack of adherence to nationally recognized consensus standards and safety practices for the fire department exposed firefighters to excessive risks and failed to remove them from a critically dangerous situation. The WVFD used strategy and tactics that were not appropriate for the rapidly developing and extremely volatile situation and exposed the firefighters to extreme risks.

• The WVFD was not trained or equipped to conduct an operation of this complexity involving a large commercial occupancy filled with hazardous materials that possessed explosive properties. Firefighters were committed to attacking a fire that was significantly beyond the extinguishment stage with few resources and a limited water supply. The limited flow available from the small hoselines deployed could not control the volume of fire. The West Fertilizer Company fire required a drastically different combination of strategy and tactics than those expected or acceptable for fighting a residential fire. (1)

|

| (7) The remains of and after effects of the blast on West Volunteer Fire Department Engine 2. |

Contributing Factors to the Explosion

The task force report listed the following factors that directly or indirectly contributed to the disastrous outcome of this incident.

1. The absence of standard operating procedures (SOPs). In my first interview with a surviving West firefighter, I asked what they did or did not know about the building and its contents as well as the initial firefighting strategy. I followed up with a request about their SOPs. The reply was something like this: “There were no operating procedures … for anything—at least not written down.”

It was recommended that SOPs be developed and firefighters be trained and educated regarding scene strategies and tactics for responding to high-hazard or high-risk occupancies. (1) This was in accordance with Texas Commission on Fire Protection standards and best practices as outlined in Fire Department of New York Chief (Ret.) Vincent Dunn’s Command and Control of Fire and Emergencies. Dunn stated that accountability and control should be clearly outlined in a general plan (SOP) for a fire department and its members [so] they know who does what and how companies should be operating on emergency scenes.2

2. There were no prefire or preincident plans for the West Fertilizer Plant. It should have been obvious that the plant presented the greatest threat to the community and responding firefighters, and, therefore, should have been preplanned. Its storing and packaging of bulk hazardous materials should have been well-documented, the stock should have been diagrammed, and an emergency response strategy and corresponding SOP should have been developed and practiced by first responders, including those from mutual-aid departments.

During the interviews, some firefighters commented that they had been to the plant, some even a number of times before the explosion, and were familiar with its contents. However, none, specifically those in leadership roles and ranking members, saw the need for or had the training or experience to know the critical importance of having a prefire plan as outlined in National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1620, Standard for Pre-Incident Planning: “The pre-incident plan should help responding personnel identify critical factors that will affect the ultimate outcome of the incident, including personnel safety and provide important data that will assist the incident commander (IC) in developing appropriate strategies and tactics for managing the incident.”3

3. Absence of the Incident Management System (IMS). The use and implementation of the IMS in coordinating, controlling, and commanding emergency operations, particularly during complex incidents, has been the standard in the American fire service for more than a decade, specifically since the events of 9/11. NFPA 1500, Standard on Fire Department Occupational Safety and Health Program, states that an IMS must be used at all scenes and that an IC is to maintain command and control of all operating forces within a common strategy.4 In West, factors identified in the analysis of fire department operations on the emergency scene concluded the following:

- –There was no incident command system, and senior ranking members did not perform supervisory roles.

- –The IC did not perform the essential duties of that position.

- –The emergency scene operation was conducted in an unstructured and uncoordinated manner, without overall direction and without adequate supervision. (1)

4. Strategy and tactics. The findings noted the fire department did not approach the incident as a commercial structure fire with hazardous materials but more akin to a typical residential structural fire; essential to controlling the blaze and protecting firefighters, officers did not initiate an appropriate firefighting strategy or any coordinated tactical plan. (1)

The fact that there was no use of any type or semblance of an IMS led to a series of challenges for the firefighters on the scene and those responding—namely, no one was clearly in charge, and there was no developing or synchronized strategy or plan to mitigate the situation or to protect firefighters. Because of this, an initial scene size-up and, perhaps more importantly, a continuous and updated reassessment of the escalating incident by a lone IC were never accomplished. This would have allowed for acute situational awareness in adjusting strategic and tactical considerations in determining appropriate crew actions (i.e., offensive or defensive fire attack and possible evacuation).

5. Firefighter safety and accountability. The report noted: “The safety and welfare of fire department personnel were not the first and foremost considerations in incident operations and decisions.” (1) In originally writing this portion of the document, the International Association of Fire Chiefs “Rules of Engagement” were always in the forefront of the team’s mind: What was the occupancy survival profile, the risk of life over savable property, and the consideration given to having crews abandon their position and retreat before deteriorating conditions could harm them?5

Firefighters were on scene only for a mere 12 minutes before the explosion. Those well-versed in fireground operations will tell you from experience that this is a “blip” in the grand scheme of things and leaves little time to do much more than provide an initial scene size-up, establish a command post, and designate assignments for first-in crews so that a carefully thought out incident action plan (IAP) could be developed. However, ICs who have the Rules of Engagement as part of their ongoing thought process will fare much better in keeping the necessary risk management and cost vs. benefit perspective when planning their actions: “How much do we risk, and for how long, to gain what?”

6. Training. The task force took exception to the fact that the state of Texas does not require minimum training standards for volunteer fire departments. This essentially leaves each agency or municipality to determine its own level of expectation and definition for what and how a fire department operates. Additionally, it was noted that West promoted its officers based on votes of the membership and not based on level of training, experience, or education.

Recommendations included minimum training goals and requirements that should be specific and increase firefighter strategy for each rank and level of responsibility, regular personnel performance evaluations, recognition of hazardous conditions—i.e., construction types and fire loads—and ensure that all firefighters and officers are trained in accordance with NFPA 1001, Standards for Fire Fighter Professional Qualifications, and NFPA 1021, Standard for Fire Officer Professional Qualifications. (1)

7-10. Prevention/codes. Theese factors involve areas of fire prevention and the adoption and enforcement of fire codes and a hazardous materials program for new and existing structures housing hazardous chemicals in accordance with or revisions proposed to NFPA 400, Hazardous Materials Code.

Prior to the incident, the state did not adopt or require fire prevention codes or a hazardous materials program for West or McLennan County. This was noteworthy because it was probable to assume that had the facility been equipped with automatic sprinklers, the fire would have been stopped in its tracks. However, as it is with the residential construction industry, most commercial businesses, even those that house bulk hazardous materials, will not take voluntary action to abide by NFPA or International Code Council (ICC) standards or install enhanced fire protection devices unless required to do so. Thus, the recommendations included calls for public policy legislation that would require governments to adopt fire and safety codes, including the establishment of a hazardous materials program and mandatory installation of automatic sprinklers for high-risk occupancies. Additionally, communities where these chemical storage facilities exist are to be better protected through the use of evacuation sirens and detailed emergency response plans. (1)

11. Discovery of alcohol and/or drug use. This was a factor in three of the incident’s deceased first responders. Although there was no indication that this material fact contributed to the firefighter deaths, it was recommended that all public safety agencies develop written policies that prohibit emergency response while under the influence of alcohol or drugs in accordance with international Association of Fire Chiefs Guide to Model Policies & Procedures for Emergency Vehicle Safety. (1)

|

| (8) An aerial view of the West Fertilizer Plant taken from the southeast in the days following the blast. |

More than any other statement in the final report, the following was the most significant in summarizing the overall opinion of the TFCA members of the task force in their review of the events for this incident:

“The final analysis of this incident does not suggest the firefighters who lost their lives, or any surviving members of the WVFD, failed to perform their duties as they had been trained or as expected by their organization. The analysis does, however, indicate a systemic deficiency in the training and preparation of the WVFD to adequately prepare for the incident they encountered at the West Fertilizer Company fire.” (1)

It is not unlikely that even in the aftermath of this and other recent multifirefighter line-of-duty deaths, some departments will continue to operate in a fashion that unnecessarily or unknowingly places their members at increased risk. This is unacceptable. Education, training, command and control, situational awareness, code enforcement, preplans, and operating procedures are all keys to providing firefighters with a foundation for success and survival. We honor the sacrifice of Firefighters Morris Bridges, Perry Calvin, Jerry Dane Chapman, Cody Dragoo, Kenneth Harris, Joseph Pustejovsky, Cyrus Reed, Kevin Saunders, Doug Snokhous, and Robert Snokhous by telling their story in the hopes that others may learn and live.

Additional Links

CSB Releases Preliminary Findings in West (TX) Explosion

West (TX) Fertilizer Explosion Report Available

Firefighting News: OSHA Partners with Fertilizer Industry to get Message out on Chemical Safety

Endnotes

1. Firefighter Fatality Investigation, West (TX); Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office, Austin, Tex. (2014).

2. Dunn, Vincent. (1999) Command and Control of Fires and Emergencies. (Fire Engineering Books & Videos, PennWell Publishing, Saddle Brook, NJ.)

3. NFPA 1620, Standard for Pre-Incident Planning (2010 ed.). National Fire Protection Association, Quincy, Mass.

4. Kalene and Sanders. (2008) Structural Firefighting Strategies and Tactics, 2nd Edition. National Fire Protection Association. Quincy, Mass.

5. International Association of Fire Chiefs Rules of Engagement for Structural Firefighting—Rules of Engagement for Firefighter Survival. 2010. http://www.iafc.org/associations/4685/files/downloads/CONFERENCES/FRI/FRI10/FRI10_spkrFCTB8-RulesofEngagementforFirefighterSafetyHandout.pdf.

BRIAN A. CRAWFORD, a 29-year veteran of the fire service, is chief administrative officer for Shreveport, Louisiana, and recently resigned as chief of Plano (TX) Fire-Rescue. Crawford is a graduate of the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer and Harvard University Senior Executives in State and Local Government programs. He served on the Texas State Fire Marshal’s Office West Firefighter Fatality Task Force as well as the Charleston (SC) Post-Incident Fire Review Task Force. He has the Chief Fire Officer designation and is an IAEM-certified emergency manager. He has a master’s degree in industrial psychology.

Brian A. Crawford will present “The Story of the West, Texas, Multiple Firefighter Deaths” on April 22 at 3:30 p.m. at FDIC International in Indianapolis.

More Fire Engineering Issue Articles

Fire Engineering Archives