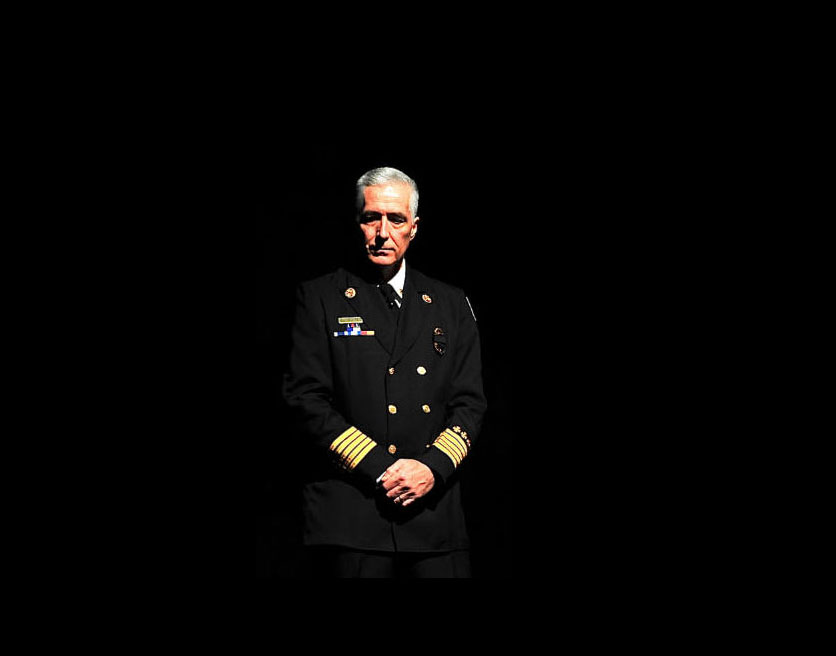

Editor’s Opinion ❘ By BOBBY HALTON

The late Tom Brennan once said, “I thought I made a mistake at a fire once, but I was wrong.” Every firefighter has had the experience of attending a “review,” a “critique,” an after-action review (AAR), or a “postincident analysis” of a run; and, if you have been on the job for more than two weeks, you have been handed at least seven National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) line-of-duty death reports and can recite the NIOSH 5 as well as your department’s mission statement. This is a good thing; these are good reports, excellent for scenario planning. They are the result of many good intentions written by earnest and good people and result in many new policies, rules, and procedures. These reports are designed to help us learn, in the hopes that we do not repeat the actions or make the “mistakes” that resulted in these reports being written.

As we go through our careers, we all make bad calls from time to time, albeit never out of bad intent. As the result of our actions, many of us have rules named after us. Some of us even have vacant city blocks as testaments to our endeavors. All of this is to say that no firefighter in the history of firefighting has ever been to a perfect fire—no one, ever. At every job, some rule gets bent a little, if not broken outright; someone misses a cue or doesn’t hear a radio call. The takeaway is that at every job stuff happens, and we still mostly win and no one gets hurt.

After every job, we do a tailboard with the troops we just worked with, the down-and-dirty blow-by-blow: What did you have? What did you do? How did it turn out? If the job was nothing special, it usually stays there, and that’s too bad. If the job has a major issue, injury, serious problems, or unusual discovery, we then hold a formal AAR. Hopefully, we hold these events not to punish or shame but in the name of learning—hopefully.

As we sat through some of those incident reviews, many of us experienced the feeling that we were hearing about someone else’s fire. Often, if the outcome was less than desired, like the fire leaving the zip code of origin or someone getting injured, the reviews could feel like the Spanish Inquisition and you were Galileo. Many of the descriptions were not quite the way we recalled them or maybe how we felt about them. Mistakes are so obvious now—three or four days later, and clearly no one should have made such stupid errors or deviated so intentionally from accepted protocols or procedures. The outcome obviously would have been different if we didn’t zig where we should have zagged; yep, we were awful.

It is even more interesting when a report is reviewed by folks who were not even there. The outside experts with briefcases have distance and, therefore, can be unbiased. Often those involved are not even heard from in the report—only spoken about. The problem is that they are biased; they know the ending, so to them everything we did looks like it contributed to the conclusion. They have no idea of what we knew or believed to be true at the time, what we didn’t know, or what we were trying to accomplish.

This is not to say in any way that we should not have reviews or AARs. What is important is how we have them, who is heard from, and if we are focused on whom or what. We get a great example of how unjust a review can be from the Navy during the final days of World War II.

On July 29, 1945, the USS Indianapolis was returning from a secret mission during which it delivered an atomic bomb when it was torpedoed. The ship sank quickly, and roughly 900 men went into the water. Because they were on a classified mission and because of the speed at which the good ship went down, they didn’t get off a distress call. After three brutal days of shark attacks, only a few more than 300 survived and were rescued.

The Navy held a review, and the captain, Charles B. McVay III, was disciplined for failing to zigzag although he was under no orders to do so. Further, the Japanese commander, Mochitsura Hashimoto, who fired the torpedoes that sank the Indianapolis, said zigzagging would not have made any difference. The Navy, influenced by 600 fatalities, needed “someone” to blame. McVay would commit suicide many years later, some say because of the unjust treatment he received.

When we look for something, we usually find it. We hit what we aim at. Look for fault, and you will find fault. When we look for the NIOSH 5, we find them. Are they “root causes”? Are they why something happened? Maybe, and maybe not. The problem is, if we find fault, error, or mistakes and we blame someone for not following rules, best practice, or whatever, then we don’t learn. The bad outcome is because they are bad firefighters and we are not, case closed.

We could try something new—well, actually, something our moms taught us: “Try walking in their shoes.” We could try to understand, try looking at what happened in context and what was decided, and figure out why we would have done the exact same thing, why those choices would have made sense to us. You see, decisions are only mistakes in hindsight. We all judge others more harshly than we judge ourselves; it is human nature. Tom would remind us that we can blame or we can learn, but we can’t do both.

MORE BOBBY HALTON

Elites, Experts, and Experience