DIVE RESCUE SERIES: LOCATING YOUR OBJECTIVE

RESCUE

Do you hear “I can’t find it!”? Or do your divers and tenders say “It’s definitely not where we looked!”?

THE OBJECT of dive search is to find people and things missing or lost underwater.

One of the things I often hear is, “We couldn’t find it. We looked everywhere and still could not find it.” Obviously, if they had looked everywhere, they would have found it. To my way of thinking, if a team can’t find an item, then they missed it.

A key element in managing a dive rescue search operation is making sure that the dive team won’t have to recheck an area. Simply stated, to be sure that there is no need to do that, your team must be positive that the item is not where they have already searched.

Lieutenant Robert Hayes of the New York City Police Department, who is head of its dive team, says that if his members cannot prove to him that it’s not there, then he makes them search again. Only after a thorough search of an area can you move to an adjacent site with certainty; part of that thoroughness is making sure the divers are indeed on the bottom and capable of finding the submerged object within a designated time limit.

Recently, a dive team spent four hours looking for a gangway to a large ship—and didn’t find it! What they found, however, was how easy it is to be overconfident because of an object’s size. It’s just as easy to think that because you’ve found an object and have surfaced to announce the good news, the problems are over. Not so. Many divers have located automobiles and the like and surfaced, only to discover it takes almost as long to find it the second time. This is where good management, premeasured lines, and attaching a little buoy to the recovered (but still submerged) object really helps.

Of course, most of the time it doesn’t matter whether we find an object by accident or by good planning, as long as we find it. When working toward a rescue, however, everything matters— good management, training, aggressive yet safe plans and contingency plans, and some good luck.

SHOTGUNNING

Poor planning leads to “shotgunning.” No, this doesn’t mean we’re goinghunting, but it is a little like shooting blindly into a forest: You load the pellets and shoot away, hoping that you’ll hit something.

“Shotgunning” is when the officer in charge of dive operations either doesn’t have a plan or doesn’t have enough faith in the plan to stay with it. Absence of a plan is inexcusable. Doubting a plan, particularly after 10 to 20 minutes of no results, is natural and happens to everyone.

Imagine yourself on a rescue site for about 15 minutes without any sign of your victim. Along come the “oh-no’s” (who travel with the “I-know’s”) to question your judgment in your choice of search sites. The first thing that comes to mind is: What if I’m wrong? Should I change sites? If you are wrong, you won’t be the first person, but what if you’re right and you move? Am I using the best search system? Did my diver miss the victim? Is he being tended well enough? These questions are normal, as is wanting to change the plan. It happens to all of us at some time or another—usually every time. You want to try anything and everything to find the victim.

DIVE RESCUE SERIES: LOCATING YOUR OBJECTIVE

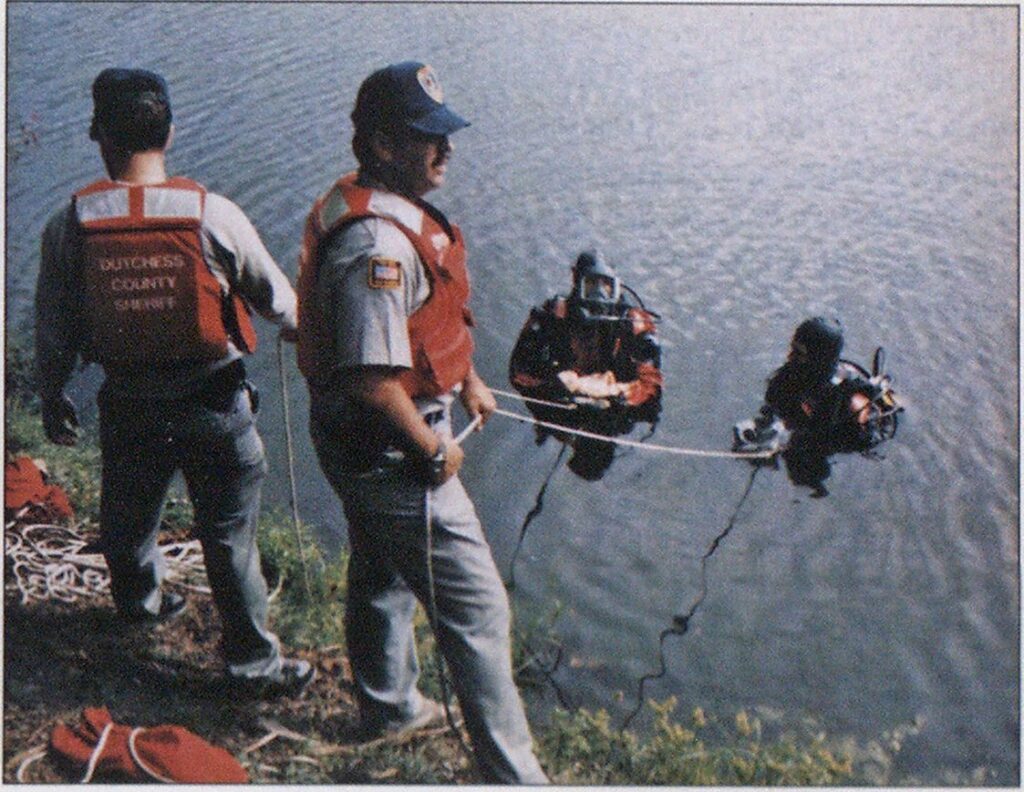

THE SUPPORT TENDER

Successful dive search very rarely can come about without effective management of the dive site, and even the best strategic management of a dive search cannot be accomplished without a competent if not top-notch support tender. Without him, all the other components on the dive site cannot operate.

It’s the tender’s job to make sure everything works. He tends to the needs of the diver and is the communicator between upper management and the inwater team. Too often we think of the diver or perhaps the boat handler as the key figure in dive operations. Our divers are often considered to be the heroes; after all, the diver is the person that goes under the cold, often black, and perhaps fast-moving water, possibly endangering his own life. Although it takes a lot of moxie to go into the water in certain conditions, there’s much more to a safe and successful rescue than what’s happening under the surface. To that end, in my mind, a good tender is worth his weight in gold.

As a diver, my personal tender is my lifeline. He and I can communicate without thinking. He knows what I am going to do before I do it. My tender can anticipate my equipment needs. He knows when I am cold, tired, or in trouble. He takes that knowledge and directs the land crew on how to deal with the problems that occur during the operation. He keeps everything safe.

The tender makes sure that 1 have all the equipment I need and that it’s properly secured. He checks safety procedures before I enter die water. He makes sure that I have a knife and that the air is turned on. He ensures that safety lines are attached correctly to my harness and shore, and that all is ready for a dive. He logs the times that I and the members of my team dive into and come out of the water and what areas have been searched. Once I’m under, he can anticipate when I will be coming up because of low air pressure. (See “Air Is Most Important,” Fire Engineering, July 1986.)

No diver should be allowed to enter the water without a designated tender, even if safetv lines are not being used.

During a New England ice rescue in the winter of 1985, a diver was lost under ice and no one knew he was missing until 12 to 18 hours after the recovery site was secured. This should never have happened. Log-in charts (see page 52) are needed and should be kept for at least one year after the dive in order to maintain complete records for future questions and review.

The diver’s job is to go underwater and search, and he needs to relay information through a safety or communications svstem to the tender and vice versa. The diver needs to be on the bottom and stay there, not come up and down with questions or answers. A good tender should be able to relay signals to his diver gently so as not to disturb the diver’s movement across the bottom.

(Photos by author.)

DIVE RESCUE SERIES: LOCATING YOUR OBJECTIVE

TTie tender must also move divers back and forth across the bottom, making certain that no portion of the bottom is missed. Poor search patterns are a combination of sloppy diving and poor tending. The diver in black water or extremely difficult conditions cannot, without top-notch directions from the surface, be sure of what areas he has covered.

By marking lines (every five feet with highlights at 25-foot increments) and keeping a chart as the rescue progresses, the tender can make sure that his diver is where he is supposed to be and that all areas are covered. Only then, when tender and divers have made a thorough, documented search, can they come back to surface management with definite proof that “it’s not there”—not with a “We couldn’t find it.” Without this documentation—proof positive that “it’s not there” —the areas must be searched again, leading to downtime (time when nothing is being done to aid the search) and a waste of personnel.

At a training session two summers ago, a team of divers watched me throw a knife into the water. They couldn’t find it. After 25 minutes, we debriefed and found that the tender’s bottom chart showed a mangled mess of twisted metal in one location on the bottom. We directed a diver back to the exact spot and, after a minute or two, he found our knife.

The key here is in “profiling”—using taped and measured lines combined with a chart detailing exactly where the divers have searched and what underwater obstructions they encountered. With this information we can precisely pinpoint the spots that need to be researched.

In a possible scenario, your tender has a graph or chart in his hand while he scans the shoreline and major shoreline items within 100 feet in both directions. He designates where he stands on the graph. The tender places his diver in the water on a measured line and the diver begins the search at 110 feet offshore. The tender notes the original 110 feet as well as each time the diver is moved inward after completing a hill sweep from left to right.

The search of the bottom can have any one of a variety of patterns. Halfmoon sweeps parallel with the shore and movements straight out and return are only two (see points A and B on accompanying chart). All movements of the diver and the diver’s signals for bottom mapping (profiling) are done by preset and practiced gentle tugs of theguide rope. Visibility permitting, the tender brings the diver in five feet at a time and again makes note of this. If on any one of these sweeps the diver finds something of special note or some difficulty in the search area, he signals this to the tender, who makes the notation on the chart.

(In our training program, different types of information get different signals and notations. For example, natural items, such as rocks and trees, are indicated by a circle; man-made items, such as cars and metal piles, are indicated by a circle with an “X” inside it.)

To return to the scenario: The tender notes that at 85 feet offshore and at 3 o’clock from the tender’s position, the diver found something of special note, such as a car. The tender responds by putting an X inside a circle on the chart. When the diver reaches an area of difficulty, such as rocks with crevices or a cave, the tender notes an empty circle. Items or clues that could aid in the search get a circle with an X. This procedure can be done again and again throughout the dive, and, when used correctly, it will allow you to place any diver back in an exact location within minutes of realizing that it needs to be re-searched.

The tender-to-diver debriefing should take place immediately after the diver leaves the water so that the diver can relate what he found noteworthy.

Training the tenders is one of the training specialist’s most important jobs. If the tenders understand their total duties and can perform them well, we will have a map of the underwater surface and all things found there and be sure—if we are unsuccessful —that the object is certainly not there. We can then continue with professional confidence until we succeed.