Advancing the Initial Attack Hoseline

STRATEGY & TACTICS

Advancing the Initial Attack Hoseline

Effective offensive, interior tactics could mean the difference between fighting to win and fighting to lose.

“ENGINE COMPANY 8, respond to the Armstrong housing complex, 126 South 5th Street. Building ‘B.’ The fire is reported on the third floor of a garden-type apartment building.”

“Engine 8, message received.”

The captain records the information on a pad, then, nodding to the firefighter at the wheel, he switches on the electronic siren. The driver flips the switch to light the emergency response lights, takes the apparatus on a sudden turn across a six-lane highway, and responds to the fire. The captain waves his arm out of the cab window’ to gain the attention of motorists. Several miles later, the pumper turns off the highway and enters an apartment house complex. The officer takes mental notes. Six buildings, each about 40 by 100 feet. Three stories. Brick. Barracks-style “garden” apartments.

The captain leans forward in the cab to look for signs of fire. In the late afternoon sun, smoke can be seen drifting down from the roof soffit of one of the apartment buildings. The driver pulls the pumper in front of the smoking structure and calls to the officer, who is leaving the cab, “Captain, we’re in luck—there’s a hydrant near the side of the building. I’m going to hook up to it.” The officer nods and continues on to the back step of the apparatus, and orders, “Stretch from the 1 ¾-inch hose bed.” The firefighters, adjusting their SCBAs and protective clothing, acknowledge the order.

The captain runs up a long path to the fire building, past a crowd of people gathered on the large grass lawn. They shout to the officer, “It’s on the 3rd floor! It’s the ‘B’ wing—the right side of the building!” Glancing up at the windows, he sees that the top-floor windows on the right side of the building are discolored and blackened.

Suddenly, the portable radio strapped over his shoulder blares, “Engine 8 pump operator to Engine 8 officer. Captain, I have a dry hydrant. I’m going to hook up to a hydrant on the next street. The water will be delayed a few minutes.”

“Engine 8, 10-4, but make sure we get water. We’ve got a top-floor job here.”

The officer, climbing the entrance steps to the building, decides to take the additional time to check the floor layout of the apartment below the fire, and runs up the straight flight of stairs. There are two metal-clad fire doors at the top of it. The captain pushes one open. He moves 25 feet down a public hallway to two apartment doors at the very end.

Banging on one of the doors, he yells, “Fire Department!” An elderly woman opens the door to her apartment. “Lady, there is a fire upstairs— could I take a quick look at your apartment?” he asks, gently pushing open the door. The woman moves aside and he steps in to survey the room layout. There is a solid wall on the left. The kitchen and bedrooms are reached from a hallway approximately five feet into the apartment. The captain makes the quick assumption that the apartment next door must be a mirror image of this one. He turns to the woman. “Thanks. Say, ma’am, you’d better leave this apartment. There may be water or smoke drifting down here from the fire upstairs.”

STRATEGY & TACTICS

ADVANCING THE ATTACK HOSELINE

Out in the stairway again, he sees the lead firefighter coming up the stairs with the nozzle and hose draped over his shoulder. The sounds of the hose butts striking the metal risers and marble steps echo loudly. Firefighters stretching the line are shouting to the men below.

“We have a stairwell. Use it!”

“Chock that door open so the hose doesn’t get caught under it.”

The captain, who has ascended the second flight of stairs to the thirdfloor level, finds the metal-clad door in the corridor blistered and charred near the top. He pushes it open slightly, and dense black smoke and a blast of heat blows out; he quickly lets the door close. The captain dons the face mask of his SCBA, and once again opens the door, but this time he crawls into the smoke-filled corridor toward the two end apartments. Visibility is zero. He cannot see the beam of his handlight. He can hear the crackle of burning dry wood. He feels the heat descending upon him. He is forced to retreat. Before turning back, he makes a wide sweep on the floor around him with his hand on the chance of finding an unconscious victim. There are no bodies. He moves sw iftly out of the superheated, smoky corridor on his hands and knees and bursts out of the fire doors.

He pulls off his face mask. The nozzleman is bleeding the hoseline of air pressure. The nozzle is cracked open slightly. Air is loudly hissing out of the nozzle.

The captain says to the firefighters, “The fire apartment is straight down the hallway about 25 feet.” The nozzleman nods his head.

Pussbfosssf

“A burst length!”

Someone in the stairwell shouts, “Captain, we have plenty of excess hose! We can remove the hose length and still make the fire apartment!”

“OK, but hurry— this thing is really starting to cook.”

The captain grabs his portable radio. “Engine 8 to Engine 8 pump operator. Shut down the pumps. We have a burst length.”

“Engine 8 pump operator, 10-4.”

As one firefighter kneels on a doubled-over section of hose, another firefighter disconnects and removes the burst length and reconnects the hoseline. The officer calls for the water over the radio.

Together again, the company is crouched down at the fire door. The line is charged. Everyone has their face masks, helmets, and gloves back on. The steady hissing of the positivepressure masks drowns out the crackling sound of the fire. Down on one knee, the captain reaches in front of the nozzleman to push open the door, and pats his shoulder. In one motion the firefighter raises the nozzle tip upward to the flaming ceiling and pulls back the nozzle handle. A powerful stream of water sprays the upper portions of the raging fire in the corridor they are about to enter.

“The nozzleman quickly raises the hose stream upward, almost directly over their

heads_Back-and-forth,

side-to-side, the hose stream is whipped frantically. The raging flames are beaten back.”

The firefighter crouched behind the officer quickly slips a wood wedge beneath the door, chocking it in the open position. Entering the flaming hallway, bunched up close together on their knees, the nozzleman, the captain, and the backup firefighter advance the attack hoseline down the hall. Bursts of flame roll over their heads at ceiling level. The nozzleman quickly raises the hose stream upward, almost directly over their heads, to stop the flames. Back-andforth, side-to-side, the hose stream is whipped frantically. The raging flames are beaten back.

Scalding water cascades down over the hose team. The flames start to spread over their heads again near the ceiling. The nozzle is used as a water curtain to block the fire’s progress. Again, the flames are pushed back down the burning hallway. Slowly, crawling one foot at a time, the team moves forward. The nozzleman’s head is down to avoid the radiant heat; he directs the hose stream ahead of him blindly. The captain behind him tries to look upward, searching the black smoke for signs of flame spreading over their heads. Suddenly, a heavy weight crashes on top of the officer’s helmet, knocking him backwards. His neck absorbs the shock. A plaster ceiling collapse. As he shakes his head, small red-hot pieces of plaster roll down his upturned collar. Despite this, the hose team stumbles several feet forward.

Crouched down on one knee, the hot concrete floor and hot ashes burn through the nozzleman’s rubber boots. His knee, resting on the floor, is throbbing. The firefighter temporarily directs the hose stream from the ceiling and down to the floor. He sweeps the hallway floor with water, but it doesn’t cool down the area beneath him. He gets up on both feet, crouched down in a duck walk. The hoseline is again moved forward several more steps.

The hose team finally makes it to the end of the corridor. Two flaming apartment doors, side-by-side, are barely visible in the smoke. Both are partly open and show flames around their frames. The officer gently pushes the nozzleman tow ard the one on the right. The officer stretches out one of his legs in front of the nozzleman and kicks open the apartment door wider.

Through the heat and dense smoke pouring out of the apartment, a faint glimpse of light from a window can be seen. The hose team crawls over the door sill and enters the apartment. The officer shouts through the hissing facemask in a muffled tone to the nozzleman right in front of him, “Go ahead about five feet and make a right turn!” ‘I’hey crawl forward, make the hose bend to the right, and the heat in the apartment suddenly dissipates.

STRATEGY & TACTICS

ADVANCING THE ATTACK HOSELINE

“Oh, God, we’re in the wrong apartment!” the captain thinks.

Then he orders his team, “Quick! Hack out! Hack out! We’re in the wrong apartment!”

They quickly pull the hose back out into the hallway. Flames can be seen inside the adjoining apartment. They step inside several feet and sweep a 15-by*20-foot flaming living room with the hose stream. They move in several more feet, turn to the left, and knock down the rest of the fire. The smoke and heat start to subside. They can feel a cool breeze from a window. “1 think we got it,” the nozzleman says.

Several hours later, after the company had returned to the firehouse, the firefighters assemble in the kitchen to review the firefighting operation.

“Say, Captain,” one of the firefighters says, “before you start we would like to say that we all agree this was not one of our better jobs. Everything that could have gone wrong, did.”

The officer raises his hand in protest. “Hold it. I disagree. I think it was one of our best firefighting efforts. True, we suffered three serious problems during the hoseline attack—a dry hydrant, a burst length, and we almost wound up in the wrong apartment—but we overcame each one of these problems and went on to extinguish the fire. We overcame three setbacks and still triumphed.

“I’ve been at fires and have seen fire companies come up against just one of these fireground problems and fall apart. The fire was never extinguished—the company could not overcome the setback. The attack hoseline never put out the fire. A lot of yelling and shouting took place and the blaze became a major alarm. We overcame three fireground problems, any one of which would have stopped an average firefighting company. I think it was a great job. It demonstrated our teamwork, training, and determination. It was in the best tradition of the fire service.”

QUESTION 1: Which of the following is untrue?

A. It is best to have as many firefighters as possible backing up on the hoseline.

B. To prevent a burst length due to water hammer, it is best to close the nozzle slowly.

C. A hose stream should be directed upwards where convection currents of heat and flame accumulate at a fire.

QUESTION 2: Which is untrue?

A. A backdraft is an explosion of combustible fire gases.

B. Flashover is full-room involvement in flames.

C. Rollover is the ignition of superheated combustible gases at ceiling level when mixed with oxygen.

D. Of the above three dangers, firefighters are more often exposed to backdraft.

ANSWER TO QUESTION 1: A Over crowding of firefighters behind a firefighter advancing a hoseline will inhibit his aggressiveness.

ANSWER TO QUESTION 2: D Firefighters are most often exposed to rollover, not backdraft.

Advancing the initial attack hoseline is a difficult tactic that exposes firefighters to many hazards. It is dangerous; it is also the most vital tactic in offensive interior attack strategy-

There are ten unexpected dangers that could kill or seriously injure firefighters advancing the initial attack hoseline.

ROLLOVER

The first danger faced by the attack team is rollover. If the door to an apartment on fire is partially opened upon arrival and a serious blaze involves two or more of the interior rooms, smoke and heat will be flowing out of the apartment door and into the public hallway over the heads of the firefighters. In the one or two minutes it takes for the firefighters in the hallway to bleed the uncharged hoseline of air, adjust the face masks of their breathing apparatus, and play out the excess hose necessary for the advance into the burning rooms, the smoke and heat flowing out of the doorway can suddenly burst into flame. It may necessitate retreat back to the stairway, and the firefighters will have to battle the flames in the public hallway to regain the area from which they just retreated. They will still have their main objective to accomplish: extinguish the apartment fire.

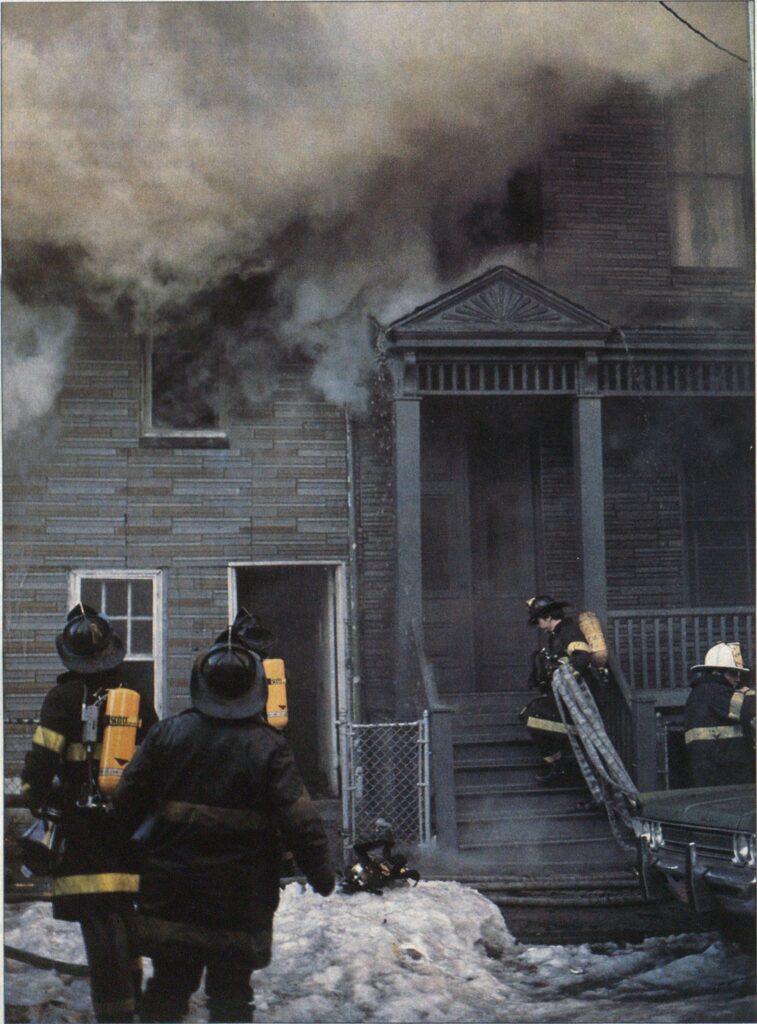

Photo by Bob Stella

This sudden flash of fire out of the apartment doorway is called “rollover,” and it could have been prevented if one of the firefighters—after making a quick search to see if anyone was lying unconscious in the fire apartment—closed the door to the burning apartment.

Rollover is a flash phenomenon that occurs when combustible gases in the smoke and heat flow out of a compartmentalized burning area and mix with air, thereby entering the flammable range and suddenly igniting. The flaming gases, being hotter than the surrounding air, cling to and flow across the ceiling in a “rolling” effect—possibly over the heads of the firefighters crouched down in the hallway waiting for water to charge the hoseline. Rollover will occur before the apartment flashes over.

Firefighters have been killed in multistory buildings by rollover. If the hallway ignites into flame and a firefighter attempts to retreat but cannot find the stairs leading down to the street, and instead climbs up the stairs leading to the upper floor, he will burn to death. When rollover occurs, the only safe exit is the down stairway.

FLASHOVER

When firefighters crawl through several smoke-filled rooms in advancing the attack hoseline, the question on their minds is, “Will this thing suddenly light up on us—will it flashover?” The most reassuring sight a firefighter with a nozzle can see is the red glow of flame through the smoke. The most dangerous time of the hoseline attack is when the firefighters are moving the hose stream forward through a superheated, smoke-filled hall or rooms without seeing flame. They must move toward the area with the greatest amount of heat without knowing the size or location of the fire. It is during this time that flashover could occur.

The technical definition of flashover is full-room involvement caused by thermal radiation feedback (reradiation) from ceilings and upper walls which have been heated by the fire. Reradiated heat gradually heats all the combustibles in a room to their ignition temperature and simultaneous ignition of the room contents occurs.

Each year, firefighters are killed by flashover; however, they are usually searching smokeand heat-filled areas without the protection of a hoseline. Hoseline protection for firefighters in which the water stream is directed for several seconds into the burning room, ahead of their advancement, can inhibit flashover. The chances of a superheated, smoke-filled house or apartment flashing over and trapping initial attack team firefighters are not that great. Rollover is a more common danger to an attack team than is flashover. This is one of the reasons why firefighters are advised to direct the hose stream at the ceiling in front of them as they move forward. However, flashover has trapped and burned firefighters advancing an uncharged hoseline.

High heat is the indicator of flashover. If the heat buildup in a house or apartment is so severe that it requires firefighters to crouch down below a heat stratification level before entering from outside the fire area, the hose stream should be charged and even discharging water at the ceiling before entering. Do not worry about water damage when there is a danger of flashover. Discharge the hose stream into the superheated smoke at ceiling level to inhibit any flashover or rollover before entering. Of the three firefighting priorities—life safety, fire containment, and property protection —the safety of the firefighter is included in the top priority.

BACKDRAFTS

The so-called strip stores, taxpayers, or row stores suffer frequent backdraft explosions because they are difficult to ventilate. Fire in a center store of a taxpayer is in a tightly confined area. There are no side windows, and the rear door is usually difficult to force open quickly due to security precautions. If there is no skylight or if it is a two-story building, roof ventilation will be delayed or impossible. The only vent opening will be the front entrance through which the firefighters are advancing the hoseline.

At this type of fire, it’s as if the firefighters are crawling into the barrel of a loaded shotgun. If there is an explosion, they will receive the full force of the blast. The blast could produce a shock wave forceful enough to blow them out of the store and onto the street; it could produce a ball of fire that severely burns the firefighters; or it could cause a partition or ceiling collapse that could block the only exit and trap the firefighters inside the burning store.

STRATEGY & TACTICS

A backdraft is an explosion caused by the combustion of a flammable gas—air mixture. It is triggered by the introduction of air into a confined space containing combustion gases from a long-burning fire that are heated to their ignition temperatures. Backdrafts generally occur in the main fire area several moments after the air is introduced to the area— usually by the initial attack team that’s advancing a hoseline.

When firefighters discuss the dangers of a backdraft explosion during training sessions, they invariably talk about warning signs. These warning signs include dense black smoke; smoke puffing around door frames; a reverse flow of smoke back into an open doorway; and discolored glass windows. Experienced firefighters, however, see all these signs at hundreds of different fires at which backdrafts do not occur. So, a firefighter should not think he can avoid a blast from a backdraft or any explosion by observing warning signs (in fact, flammable vapor explosions, BIJEVEs, and pressurized container explosions don’t exhibit any warning signs).

Explosions happen tot) fast —there is no time to react. The only protection a firefighter has against an explosive blast is his protective equipment: gloves, mask facepiece, helmet earflaps or hood, turnout coat, pants, and boots. All exposed areas of the firefighter caught in the backdraft explosion may be severely burned. A firefighter advancing a hoseline with protective fire clothing should be able to take the full blast of a backdraft. If a firefighter does not have full fire gear with mask facepiece and gloves, and explosion occurs, he will probably never extinguish another fire.

OVERCROWDING BEHIND THE ATTACK TEAM

Additional firefighters crowding behind a hoseline attack team can lead to serious consequences:

- The additional firefighters could accidentally push an attack team member forward into a compromising position.

- The additional men could block or delay backup or temporary retreat to escape a blast from flashover or backdraft. Firefighters behind the attack team will actually be shielded from any blast of heat or flame; by the time they do feel it and reverse direction for retreat, the nozzle team will be seriously burned.

- Crowding will inhibit an aggressive, forward-moving hoseline attack. A firefighter holding a nozzle will aggressively push forward down a burning hall at a serious fire when he knows there is room for a temporary retreat or knows he has the ability to temporarily stop the advance for several seconds without being pushed ahead.

The area directly behind an attack nozzle team must be unblocked, or guarded by only one or two company members; this will permit a temporary retreat if there is a blast of heat from a vented window on the other side of the fire or from an interior explosion. (The explosion dangers in a typical burning house are: gas accumulation from broken or melted stove pipes, vapors from an arsonist’s flammable liquid, propane cooking or torch cylinders, household pressurized containers, exploding window air conditioning units, kerosene containers used for space heaters, imploding television tubes, smoke explosions caused by double-pane insulated windows, and backdrafts.)

The advance of a hose stream at a serious fire is not a continuous forward charge. It is a slow, erratic forward movement. It has short stops to cool-down areas, and even short retreats along the way. The firefighter must have this psychological advantage (knowing his path to safety is clear).

ADVANCING A HOSELINE AGAINST THE WIND

When the wind velocity is in excess of 30 miles per hour, the chances of a conflagration are great; however, against such forceful winds, the chances of a successful advance of an initial hoseline attack on a structure fire are diminished. The firefighters won’t be able to make forward hoseline progress because the flame and heat, under additional force, will blow into the path of advancement.

When the door to a fire area is opened and strong wind is blowing from an opening at the opposite end of the structure, the actual point of fire origin may be several rooms back, out of the reach of the hose stream. The flame blowing out of the doorway will be the tip of the flame—actually the superheated gases igniting upon mixture with air. A hose stream directed at this flame will have no effect since the real generation of heat is several rooms removed from the flaming doorway.

STRATEGY & TACTICS

ADVANCING THE ATTACK HOSELINE

To prevent serious burn injuries, firefighters encountering this situation must change their strategy. The interior line is withdrawn and the door to the fire area closed. The officer-in-command must be notified of the inability to advance the interior attack hoseline due to the strong wind. A second hoseline is advanced on the fire from the opposite end, the window or door through which the wind is blowing.

This may require that firefighters stretch the line up an aerial ladder, fire escape, or portable ladder. The second attack hoseline will advance on the fire from the upwind side. The initial attack team, behind the now closed door, must maintain their position to prevent the fire from extending into the public hall and to protect civilians and firefighters who may be using the interior stairs. Before the second attack team advances, the officer in command of the hoseline must contact the first attack team to ensure they have safely retreated behind the closed door and will not be injured by the heat currents and steam created by the opposing hoseline advance.

PASSING FIRE

When a new firefighter in rookie school learns the fireground tactics of advancing an attack hoseline, a company is told, “Never pass fire. It could cut off your escape and trap you inside a burning building.” However, when the firefighter gets assigned to a company, the fire chief and the officer sometimes order him to stretch the attack hoseline to locations which require him to “pass fire.”

For example, at a house fire a company is ordered to stretch the second hoseline to the floor above the fire. To do this, they must pass the fire that’s not yet extinguished by the first hoseline on the fire floor. Or perhaps the response is to a serious fire that has extended to the stairway of a three-story residence building. The captain orders the first line to “darken down” the fire which started on the first floor and then to proceed quickly up the flaming stairway to the top floor, extinguishing fire as they go. However, on the way up the stairs a smoldering baby carriage in the hallway is passed; burning bags of garbage in the hall on another floor are passed.

Why were they passed? As an unqualified statement, “Never pass fire” is inaccurate. It should be rephrased, “Never pass fire which threatens to spread or increase in size to cut off your retreat or escape” or “Never pass fire if a second hoseline has not been stretched when there is a threat of fire spread or increase in size that could cut off your retreat or escape.”

When ordered to stretch the first hoseline at a stairway fire, the officer should request the chief to stretch a second hoseline to back up the advance of the first. However, if there is a delay in the second hoseline and there is a serious threat of fire spreading out below and cutting off the attack hoseline that’s progressing up the stairway, the company officer should not expose the company to fire cut-off. He should instead wait for the backup line or leave a firefighter at the point where fire is passed to warn the first attack hoseline team of any potential fire spread and danger of being cut off. Likewise, when the second attack team is ordered to stretch a hoseline to a floor above, the officer of that company must visually check that the initial hoseline is charged and controlling the original fire floor—before going up the stairs.

The fire officer should never allow his company to pass fire that threatens to cut off retreat. If the officer cannot accomplish the assigned task due to such a threat, the chief-in-command must be notified.

BURNS FROM COLLAPSING PLASTER CEILINGS

Sections of plaster ceilings often collapse down on firefighters as they advance the initial attack hoseline. Large, thick portions of falling plaster ceilings can knock firefighters unconscious, cause the firefighter to drop the nozzle, and rain hot pieces of plaster, melting paint, and sparks.

Ceiling collapse is caused by water absorption into the plaster from the hose stream. As firefighters move through a burning room or hallway, they direct the stream at the upper levels of the fire area to cool the atmosphere before crawling forward. While some of the plaster is broken and knocked down by the force of the hose stream, some of the water is absorbed by the remaining plaster or ceiling. As the firefighter with the nozzle continues advancing, the water-soaked, red-hot plaster ceiling sometimes suddenly collapses, striking the firefighter on the head or crashing down on his shoulders, with pieces rolling down the turnout coat collar, or up the sleeves of the firefighter directing the nozzle upward. Some of the hot embers are even caught by the top part of the boots. These red-hot embers often burn the neck, wrist, and knees of the firefighter as he continues to move forward to extinguish the fire. If it is not hot plaster from the ceiling falling on the firefighter, it will be sparks, scalding water, or melted paint.

However, to the firefighter advancing the hoseline, these hazards come with the job —the real danger and concern is the unquenchable, roaring flames that are raging directly in front of him. If the firefighter understands and expects the likelihood of getting burned by flaming substances from above, he can prepare for it.

FLOOR-DECK COLLAPSE

When a mask-equipped firefighter crawls blindly forward in smoke, crouched down below the flames and heat, directing the nozzle stream at the ceiling overhead and being bombarded with hot pieces of falling plaster, paint drippings, scalding water, and sparks, he is depending on the floor to support his advance. The firefighter can endure the flame, heat, smoke, and falling hot objects and still move forward with the hoseline, but he cannot advance if the floor shows signs of collapse. The firefighter must have a stable floor from which to mount a hoseline attack and extinguish a fire.

STRATEGY & TACTICS

The floor of a burning room can generally be depended upon to support the firefighters advancing the hoseline; flames and heat rise, so the floor does not usually present a collapse problem. However, over the past two decades there has been an increase in fire-weakened floor-deck collapse, and firefighters advancing hoselines are plunging through with increasing frequency and sustaining severe burns.

Increased incidence of floor-deck collapse is mostly attributable to arson. An arsonist’s flammable liquid spilled on the floor burns on top of and under the flooring material. As the firefighter crawls forward he may suddenly feel the floor deck give way, and one or both legs may plunge through it. If he is unable to quickly pull his legs up out of the floor holes or if other firefighters cannot free him, he will be seriously burned, straddling a charred floor beam or hanging between beams in the burning floor space.

To avoid this danger and safely advance a hoseline through several burning rooms, crouching firefighters should keep one leg outstretched in front of them. Body weight will be supported by the back leg tucked beneath it, while the outstretched leg can feel the stability of the floor deck or holes before further advance.

A serious fire raging below the flooring on which the firefighter advances a hoseline poses a greater danger of floor-beam collapse in addition to a floor-deck collapse. The entire section of floor fails, dropping the firefighter down with it into the burning floor below. Bathrooms should be considered areas where floor collapse often occurs when fire on the floor below weakens the floor beams. Also, firefighters should realize that a cement tile or terrazzo floor in a restaurant or kitchen will conceal a dangerously fire-weakened wood floor beneath it; they should know the size and intensity of the fire below these types of floors before advancing a hoseline across them. Furthermore, the area around heavy machinery, stoves, and refrigerators will collapse first when the floor is weakened by fire in a cellar. Firefighters advancing hoselines on a floor above a serious fire should avoid areas around heavy equipment. The reach of a hoseline should be used to extinguish fire, while firefighters stay a safe distance away.

INCORRECT USE OF MASTER STREAMS

The powerful, high-pressure master stream directed through a window from a close-up approach can collapse an interior partition wall down on top of firefighters; used inside the burning building, it can also explode several cinder blocks out of a wall that separates a burning apartment from a public hallway. A master stream directed into a burning room can create a scalding steam and hot water spray that can burn firefighters who are directing a hoseline at a doorway. If directed at flame through an apartment window, the master stream can create a blast of superheated entrained heat and flame that can travel through several rooms. If it strikes a firefighter in the chest, it could sweep him off a roof, knock him out a window, or down a flight of stairs.

A master stream is sometimes put into operation at a burning residential building when an interior attack hose team cannot advance on a fire. At some fires, the interior attack line cannot extinguish the fire because of its inaccessibility to such areas as a fully involved attic or cockloft; or because of the large amount of fire at such difficult structures as a factory mill or high-rise office; or because the wind is blowing into a window against the hoseline advance.

Over the years, firefighters operating interior attack hoselines have been injured by outside master streams. Sometimes the injuries are caused by the fire chief ordering the outside master stream into operation before getting confirmation from the interior sector commander or company officer that all firefighters have been safely withdrawn; other times the injuries are caused by interior sector commanders or company officers who stubbornly refuse to change tactics and withdraw when the situation warrants it; sometimes the injuries are caused by the firefighter or fire officer who improperly directs the master stream without waiting for orders from the chief. Whatever the cause, poor firefighting tactics are almost always involved.

To set a master stream in operation safely requires coordination between three people: the chief-in-command outside, the interior sector commander inside, and the firefighter or officer in charge of the master stream. The chief-in-command must receive confirmation from the interior commander that all firefighters are safely positioned or have been evacuated before starting a master stream in operation. The interior sector officer must have effective command and control over all of his firefighters and comply with the chief-in-command’s orders to back out or withdraw interior firefighters to safety; the fire officer or firefighter in charge of the master stream must not direct it into the burning building until receiving orders from the chief.

INCORRECT SIZE-UP FROM INSIDE A BURNING BUILDING

The size-up of a fire can be accomplished from inside and from outside of a burning building. An inside sizeup is often made by the fire officer in charge of the initial interior hoseline attack. The foreground commander, outside of the burning building at the command post, will make the outside size-up. This commander will usually first request a size-up from the inside attack team, then make his outside size-up and transmit a radio status report of the operation.

Photo by Warren J. Fuchs

At the initial stage of a fire, the inside size-up is more accurate and useful than the size-up made from outside the fire building: the fire officers inside the structure are closer to the fire and, obviously, can see more of it than someone standing outside. Often upon arrival at a fire located at the rear of a house or row of multiple dwellings there is no flame or smoke visible at the front of the building. At such a fire, the officer making the inside size-up will discover the true seriousness of the blaze and report it to the chief. Conversely, at some fires the outside of a burning building may appear to be engulfed in flame and smoke, but the inside size-up will indicate that the fire is confined to one room and can be quickly extinguished with one attack hoseline.

Inside size-up is more accurate at most fires. However, there is one type of fire for which outside size-up is always more accurate, and failure to recognize it may cost firefighters their lives. This type of fire initially shows flame at only one lower or intermediate floor of a multistory building, but soon after the first attack hoseline is advancing in on the fire, the flames rapidly spread to several floors above. At the latter stages of this large-scale fire, the outside size-up will be more accurate than the inside size-up; in fact, size-up by the officer in charge of the advancing attack hoseline may be dangerously incorrect. From his limited view inside, he could believe that the fire involves only one or two more rooms on his floor that can be quickly extinguished by the hose stream, when actually the entire building is involved in fire above the company and possibly in danger of collapse.

This condition can occur when fire spreads up an open elevator shaft, or through a vacant or partly demolished building that has numerous holes in the floors, or in timber truss-roof buildings. There have been several documented incidents in which fire chiefs have ordered advancing interior attack teams on lower floors to leave the hose and retreat out of a burning building because fire rapidly spread to upper floors, threatening collapse, yet firefighters inside, unaware of the condition, did not quickly obey the order. Such incidents reinforce the importance of recognizing a fire that requires strictly an outside size-up and of immediately complying with a chiefs order to vacate a burning building.

Fighting a fire by advancing an attack hoseline down a hallway or through several flaming rooms of a house is dangerous, but it also is the most effective way to extinguish a fire. It saves lives of trapped people and reduces property damage by preventing the spread of flame and smoke to adjoining buildings.

A hoseline attack is the basic firefighting service provided by the fire department to the community. The youngest firefighters are usually the ones assigned to this critical firefighting task. Advancing a hoseline through flames requires their strength, determination, and courage. When the initial attack line can be rapidly advanced through the structure to the seat of the fire unimpeded, containment, control, and extinguishment can be more quickly assured. If through training and experience this becomes standard operating procedure at structure fires, it allows everyone else to perform their duties with more safety and efficiency.