By DENNIS MERRIGAN

Philadelphia (PA) Fire Department Former Commissioner Harold Hairston once said, “You can’t do more with less; you can only do less with less.” Like every government department or bureau in existence, the fire service is perpetually dealing with budget issues that are often a source of compromise within an organization. Budget constraints drive and affect performance and service delivery in many ways. From apparatus and equipment to staffing and training, funding drives the agenda. Inadequate funding or funding reductions without corresponding service reductions create pressure to keep fire service delivery at precut levels—the proverbial “do more with less” mentality. In an organization like the fire service, this ill-advised drive to do more with less is often at the root of unsafe practices. This article examines how issues relating to your budget can negatively impact safe operations.

Managing the Aggression

Typically, firefighters are “Type A” people. Very little will keep them from completing a mission, even at direct risk to their personal safety. That drive, determination, and calculated disregard for their safety are what allow them to do the job we ask them to do. However, as leaders and managers of this service, we are obligated to channel that drive and desire in ways that keep them within the parameters of safe operations. Often, concepts such as completing the mission and safety come into direct conflict, but they should never be allowed to compete with each other.

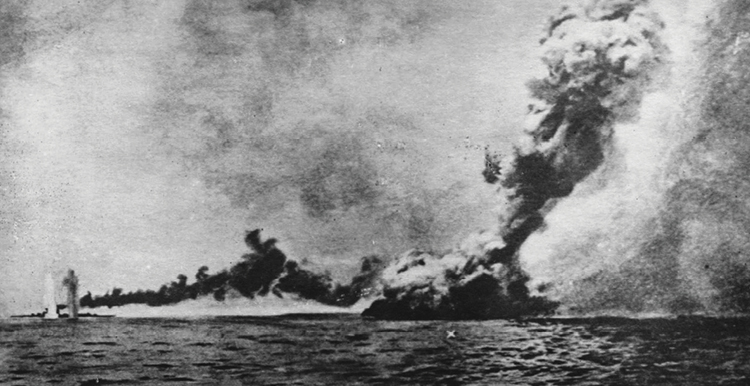

(1) Explosion of the British battle cruiser HMS Queen Mary during the Battle of Jutland on May 31, 1916. Of the 1,266 crew members, only 20 were rescued.

Organizations, especially the fire service, are good at increasing the demands on their people and equipment. However, the fire service isn’t good at reducing demands because of budget and personnel constraints. Over time, this leads to “mission creep,” a term first used by the military to describe the process where an organization’s mission expands far beyond what was originally intended. A good example of fire service mission creep is the way many fire departments have taken on the obligation of emergency medical services (EMS). Over the course of a generation, the fire/EMS mission has exploded.

Many fire departments have complained repeatedly that their budgets, personnel, equipment, and training have not nearly kept up with the demands of this adopted mission. Predictably, this mission creep has caused problems not only with EMS delivery but also with fire suppression delivery. Many departments now respond to so many EMS calls (as EMS consumes even greater amounts of their budgets) that firefighting and the training and equipment necessary to execute that fundamental mission competently have suffered enormously.

The British Grand Fleet

During the early part of the last century, the British Empire spanned the globe; its Navy was tasked with defending this vast empire. Keeping the sea lanes open for the island nation was a top priority. Even with this imperative mission, budget constraints led to some questionable maritime decisions by what was, at the time, the world’s greatest Navy. The following account from history illustrates this problem:

“Admiral Fisher was appointed not so much for his ideas on naval warfare, but rather that Lord Selborne, the First Lord of the Admiralty and civilian head of the Royal Navy, recognized that Fisher ‘was the only admiral on the flag list willing and able to find economies in naval expenditure.’ His challenge was to reduce naval expenditures whilst combating the threat of armored cruisers to the Empire’s trade routes, meeting the threat of torpedo-armed small craft and submarines, and still maintaining a force of battle-worthy combatants to destroy hostile enemy fleets.”1

This sounds a lot like mission creep, the “do more with less” mantra we deal with today. The British Fleet, originally charged with defending the home waters, found itself tasked with keeping the sea lanes open for its global empire. It’s not uncommon for fire service leaders to be appointed chief or commissioner for the expressed reason of reducing the perceived “bloated” budget of a given department. Out of this economic and political pressure was born the “Battle Cruiser,” a warship that would go down in history for all the wrong reasons. Evidence suggests that this cost-cutting scheme did what it was expected to do: save money.

“The team of Fisher and his civilian superior Selborne was very successful in that their overall program of cutting old warships, geographic re-balance of the fleet, and introduction of new types of vessels kept British naval spending at or below the levels of 1906 for five years.” (1)

Cutting Corners

When it comes to modern firefighting, cutbacks in areas such as equipment, training, staffing, and hiring have caused many firefighters and departments to correspondingly cut corners. In many cases, this has led to disaster and has been a root cause in many line-of-duty deaths (LODDs). The reductions in training time, hiring of new personnel, purchasing of new equipment, and maintaining infrastructure are all examples of how organizations suffer because of fiscal constraints.

Over the course of my career, I’ve had to deal with ill-conceived, budget-induced schemes such as elimination of training, rolling brownouts (rotating closures of selected fire companies), task forces (short-staffed engine and ladder companies designated to operate as one unit), and outright elimination of frontline fire companies. When firefighters operate at incident scenes unsafely and then analyze the reasons behind it, we can break this down into the following three categories:

- Ignorance. The firefighters were unaware of the policy or procedure governing the act. You can usually address this simply by making them aware of the policy/procedure in question. For example, they are not wearing personal protective equipment properly.

- Flagrant disregard. Firefighters know about the policy and procedures but refuse to comply. This is, in my experience, a scenario that may lead to discipline. One example of this would be unsafely driving the apparatus.

- Adaptive culture. This is the most dangerous of the three categories. This is the set of collective, informal norms or conduct that arises in an organization in response to negative, external influence over the course of time. A key element of adaptive culture is the tacit approval of the controlling authority.2

Adaptive culture is what causes many firefighters to knowingly violate safety rules, even though they clearly know better. However, they do it in a way that doesn’t provoke disciplinary action since the controlling authority understands this culture and tacitly approves of these practices. When a city or town council decides to save money by reducing staff on its department’s engine companies from four to three, the three-member crew’s workload isn’t cut accordingly. When they arrive at a dwelling fire at “zero-dark thirty,” they still have the same multitude of tasks to accomplish as before. Faced with this pressure (literally life and death), those three Type A people start taking shortcuts to maintain their previous level of performance.

Often, the chief is placed in an untenable position with inadequate resources and tends to overlook these shortcuts, especially if the crew’s performance results in a life saved or a “good stop.” Over time, these informal shortcuts become informal departmental standard operating procedures (they become institutionalized) and are passed on to the next generation without question or objection. Other companies take note and follow suit. What started as a dangerous shortcut is now a cultural norm. This is adaptive culture.

This situation is closely related to the Hawthorne Effect, which is “a psychological phenomenon that produces an improvement in human behavior or performance as a result of increased attention from superiors, clients, or colleagues. In a collaborative effort, the effect can enhance results by creating a sense of teamwork and common purpose. In social networking, the effect may operate like peer pressure to improve the behavior of participants.” (2)

As a result, the engine company members in the above example unite in opposition to the budget cuts and decide they will show (insert villain here) what they can really do; the “we’ll show ’em mentality” takes over. This attitude can result in anything from reckless driving to “covering the ground of the browned-out company” in the adjoining neighborhood. Sooner or later, that same chief who looked the other way at Engine 99’s “unusually quick” responses will end up investigating Engine 99’s accident. The exposed local government is now on the hook for millions of dollars or more in accident-related costs, including lawsuits and the possibility of lives lost.

There are other reasons adaptive culture institutionalizes safety compromises. In some cases, this could mean making up for perceived organizational shortfalls. The following example from naval history illustrates how adaptive culture can have catastrophic results.

The Battle of Jutland

This battle is the perfect example of adaptive culture and was fought in 1916 between the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet and was the only major naval engagement of World War I. It was also the greatest clash between battleships in history. The British fleet outnumbered the German fleet 151 to 100 ships. On paper, the Germans should have never left port, but German Admiral Reinhard von Scheer—in response to the British naval blockade—wanted to draw part of the British fleet into a trap and destroy it. Scheer had no idea the entire British Grand Fleet had put to sea. What was supposed to be a limited engagement ended up as one of history’s biggest naval battles. Despite their vast fleet’s superiority, the British suffered the catastrophic sinking of three battle cruisers (among others) and approximately 6,000 sailors killed in one afternoon.

(2) The battleship New Jersey was the last and best designed of the big-gunned battleships. Navy crews on similar ships learned to take shortcuts because of design and training shortcomings. These institutional shortcuts eventually led to the unnecessary deaths of thousands of sailors. (Photo by author.)

It’s the loss of these battle cruisers—Indefatigable, Queen Mary, and Invincible—that history remembers because of their sudden and complete destruction with the loss of nearly all hands. During the battle, the British ships exploded and sank unexpectedly. These three ships alone account for nearly half of the 6,000 English sailors lost that day. Why were three ships of the line utterly destroyed by massive explosions? The answer seems to be adaptive culture, as explained by author Michael Peck:

“British doctrine in World War I emphasized smothering the enemy with rapid broadsides, even at the expense of safe ammunition-handling procedures. This made British warships more vulnerable to ammunition explosions. Indeed, it is worth noting that the German battle cruiser squadron came under fire from most of the British battleship contingent, but most of them managed—albeit badly battered—to reach port.”3

Battle cruisers were designed as a cost-saving measure. They were fast, heavily gunned warships, but to achieve this high speed, they sacrificed armor protection; they were never meant to engage battleships. To compensate for their budget-induced design shortcomings, the British sailors on the battle cruisers decided to take shortcuts in their handling of ammunition.

Author Jeffrey T. Fowler writes about how British crews adapted to their conditions:

“The Germans concentrated on armor protection and accurate naval gunnery. The British became obsessed with rapid firing as a technique for keeping enemy ships off balance. While the Royal Navy had strict procedures in place regarding the number of bags of cordite and shells that could be removed from magazines and made ready for firing, ships’ crews routinely ignored these safety precautions.”4

Next, the Admiralty approves:

“In 1913, British Commander-in-Chief, Home Fleets, Admiral Sir George Callaghan requested that the basic ammunition load on British battle cruisers be increased from 80 to 120 rounds per gun. This request was subsequently approved, creating a dangerous safety situation.” (4)

The safety implications of this order were staggering:

“When the guns were combat ready and had available rounds in all spaces in the turret and ready room, each gun carried about 46 additional rounds and cordite charges in the critical spaces between the magazines and the gun turrets. In practice, this meant that each eight-gun battle cruiser at Jutland carried a total of 960 shells and 290,000 pounds of cordite propellant. This was approximately 50% more ammunition than the original specifications of the battle cruisers required.” (4)

Overpacked with shells and powder, the (relatively thinly) armored battle cruisers’ fate was sealed before the battle even started. The British battle cruiser doctrinal weakness was exposed; the catastrophic but predictable results:

“Once an enemy shell pierced the poorly armored turret of the ammunition-filled British battle cruisers during the Battle of Jutland, the immense stacks of cordite propellant initiated a flash fire. The fire then traveled down the open elevators and blast-shutter curtains, igniting the main powder and projectile magazines.” (4)

The resulting explosions sent three British battle cruisers to the bottom of the North Sea with nearly all hands perishing. A fourth—HMS Lion—escaped this fate only because of the last-minute heroics of turret commander Major Francis Harvey. Harvey ordered the magazines to be flooded, preventing the same kind of catastrophic explosion that claimed HMS Lion’s sister ships. He later died of his injuries and was awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously.

The British Navy was spoiling for a fight with the German fleet for many years. Their desire to destroy the Germans (e.g., accomplish the mission) when the time came to engage became an obsession. That obsession over time led the sailors to cut as many corners as they could to increase their rate of fire. Cutting corners by using unsafe ammunition-handling and storage practices allowed them to shave precious time off firing their massive guns. However, the downside to these unsafe practices had catastrophic results when the unsafely stored powder detonated during the battle they so eagerly sought.

Safety Processes Ignored

Adaptive culture was cultivated in the British Navy slowly:

“Prior to the destruction of the three British battle cruisers at Jutland, many well-meaning officials were involved in the decision-making chain. British naval planners and commanders had put in place both mechanical design features and procedural safeguards to protect their ships and crews from catastrophic ammunition-related explosions.” (4)

Safety was originally part of the Navy’s thinking, but it slowly eroded to compensate for shortfalls in budget-induced deficiencies throughout the fleet:

“Unfortunately, naval leaders and the commanders of individual vessels allowed their fear of not having enough ammunition during battle to override these mechanical and procedural safeguards, with tragic results. A formal investigation of what caused the destruction of the three British battle cruisers at Jutland was later conducted, but it was officially disregarded for political reasons.” (4)

Perhaps the last line in this excerpt is the most troubling while at the same time the most compelling:

“A formal investigation of what caused the destruction of the three British battle cruisers at Jutland was later conducted, but it was officially disregarded for political reasons.” (4)

This is “stone cold” evidence of adaptive culture. Here, we see the critical element: The tacit approval of the controlling authority is clearly present and documented. In this case, the British Admiralty knew not only about the improper handling of ammunition and powder charges, but they authorized the requisition of 50 percent more powder than the basic design load allowed for, thereby fulfilling a key element of adaptive culture. Further, the inquiry that would have exposed this failure was suppressed.

The failure to learn from their mistakes would manifest itself in the initial stages of World War II when, once again, a British battle cruiser—the HMS Hood—was blown out of the water with a loss of all but three crew members as it confronted the mighty German battleship Bismarck. This is the same lesson we get from every National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health report on a fire service LODD. The circumstances and critical elements are all too often well-known and predictable.

Although the Battle of Jutland provides a tragic, historic example of how disastrous adaptive culture can be, it isn’t hard to find examples of this toxic process playing out in today’s modern fire service.

Budgets are about money, and battles are about people. At least one-half of the 6,000 British sailors who died in the Battle of Jutland were victims of their desire to maintain the high traditions of their service while simultaneously dealing with outside pressure to do more with less. The American fire service culture is equally strong and proud. It’s time we learn from history.

References

1. Lazarus. (December 16, 2014). The Enduring Myth of the Fragile Battle Cruiser. Retrieved August 22, 2017, from http://www.informationdissemination.net/2014/12/the-enduring-myth-of-fragile_16.html.

2. Rouse M. (August 2014). What is the Hawthorne effect?–Definition from WhatIs.com. Retrieved August 21, 2017, from http://searchhrsoftware.techtarget.com/definition/Hawthorne-effect.

3. Peck M. (September 13, 2015). Battle cruisers: The Glass-Jawed Warship that Failed. Retrieved August 22, 2017, from http://nationalinterest.org/feature/battle cruisers-the-glass-jawed-warship-failed-13828.

4. Fowler JT. (July 13, 2017). Maritime Risk and Safety: Battle of Jutland Exposed Flaws in British Naval Procedures. Retrieved August 22, 2017, from http://inmilitary.com/maritime-risk-safety-battle-jutland-exposed-flaws-british-naval-procedures.

DENNIS MERRIGAN is a 25-plus-year veteran of and a deputy chief with the Philadelphia (PA) Fire Department and is assigned as its incident safety officer.