By Ty Wheeler

As I discussed in my first article, strength needs to be the foundation for any tactical athlete’s program. To be successful on the fireground, we need to be able to perform our duties effectively and efficiently while avoiding injury. And, developing this foundation of strength will enhance our fireground abilities by reducing the maximal output in performing our task. For example, to rescue a down firefighter in a Mayday situation, we need to have the strength to move the weight of a 200-pound firefighter through a dynamic environment in compromised positions. Not only does your victim weigh 200 pounds, but when you add the weight of the equipment (100-plus pounds) and your body weight, you will have to move nearly 500 pounds in these situations.

Strength will reduce the stress we exert on the fireground if we can generate high muscular output—either force or power. If the above example features two rescuers, and “Rescuer One” can only dummy drag or dead lift 185 pounds and “Rescuer Two” dead lifts 450 pounds, Rescuer Two will have an easier time moving the victim and is at a decreased chance of injury because of the ratio of weight of the victim compared to his one-rep max. This allows Rescuer Two’s endurance to be increased and have a much lesser max effort.

Needs Assessment

When beginning a tactical strength program, the first step is to complete a needs assessment. This will identify the firefighter’s weaknesses in strength, technique, and mobility. You can accomplish this by performing a variety of assessment-based movements and exercises, which can range from squats to sprints, depending on your strength coach.

A needs assessment must also include other factors such as job-related duties, environment, and injury assessment. As a strength coach, your priority is to ensure your personnel remain healthy and to prevent injuries. Identify any current or previous injuries or medical conditions your personnel have and adjust their programs accordingly.

Next, the environment we conduct our operations will also dictate the type of programming for our athletes. Structural and wildland firefighters are going to face vastly different environments. Although these athletes will be conducting similar training programs, the ratio of strength to conditioning may be altered based on their operational environments and duties.

Program Design

As we briefly reviewed in the first article, there are many different programming variations we can perform based on our needs assessment. The best type of programming for tactical athletes will focus on either an upper/lower split, a push-pull split, or a full-body split (trains all muscle groups in each workout). This will focus on developing a well-rounded athlete while incorporating job-specific exercises. To build strength, a core lift should be the focus of each workout conducted at a high intensity or heavy weight. Rotate these exercises between squats, deadlifts, overhead presses, and row or pull movements. I will discuss these later in the article.

The exercises performed need to be varied to introduce different stimuli and to allow the body to grow. I discussed the different periodizations and cycles of set and rep protocol to enhance strength and hypertrophy. As the athlete begins to develop a solid foundation of strength, we can begin to further alter the set/rep protocol week to week and even day to day. Each athlete should try to weight train four days per week and perform specific physical preparedness (SPP) three days per week.

Recovery

As a rule, we need 72 hours for adequate recovery between heavy, high-intensity strength work for specific muscle groups. This allows the muscle to recover and repair from the high demands, but more importantly it allows the central nervous system to recover from the high volume of stimulus. For instance, if you train lower body on a Tuesday, allow 72 hours to perform another high-volume or high-intensity training session for the lower body. This is a basic rule for high-intensity, max-effort lifting. Recovery needs will depend on volume and intensity performed during each workout.

Posterior Chain Development

As the name suggests, the posterior chain consists of three posterior muscles: the lower back, the hamstring, and the glutes. This group of muscles involves much of the posterior back muscles and are responsible for extension, stability, and forward movement. Dan Blewett of T-Nation says, “The posterior chain is the most influential muscle group in the body. The glutes, hamstring, and low back tremendously affect your athletic prowess: they’re the prime movers of forward propulsion.”1 It has also been identified as one of the most neglected and underdeveloped muscle groups in most individuals. Our culture and society promotes a sitting position for many of our daily activates and effects these muscles. Kelley Starrett, a world-renowned movement expert has stated, “Sitting is death. It causes muscle tightness, but that’s not all. Long periods of sitting devours your athletic potential.”2 A lack of strength in the posterior chain has also been associated with increased back injuries.

Your program’s priority design needs to be focused on the posterior chain, as it accounts for most tactical athlete’s injuries. The posterior chain has primary movements and accessory movements. Primary movements include the deadlift, good mornings, the Romanian dead lift, glute-ham raises, reverse hyper, and barbell thrusts. These exercises will be the primary exercise around which you should build your workout. Accessory exercises will build capacity and develop overall movement; these include the back extension, the Bulgarian split squat, the sled drag, and so on.

Exercise Order

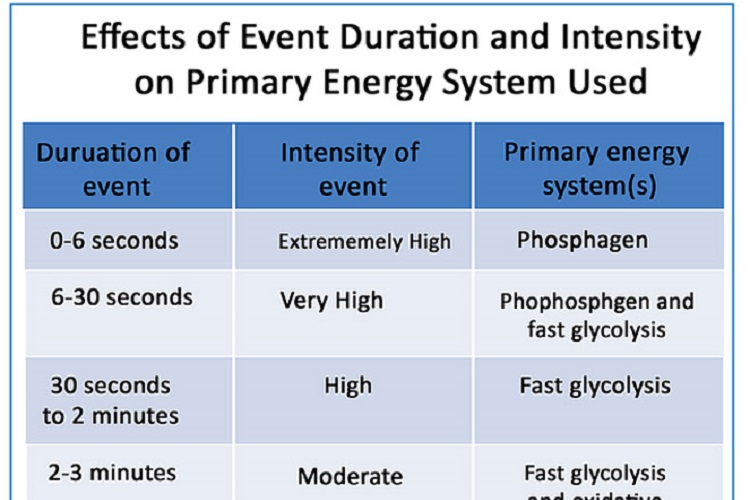

Exercise order is the final piece of the program design. Once you have selected the program design and ensured you are incorporating posterior chain exercises, perform your exercises in a specific order for greatest effect and adaptation. Our body uses the following three energy systems:

- The Phosphagen System. This system is active at the beginning of any workout and is responsible for powerful, explosive movements usually lasting 0-6 seconds in duration (anaerobic movement). Movements for this system are used in Olympic lifting, plyometrics, and sprints.

- The Glycolytic System. This system is responsible for medium duration activities. It can also be broken into fast and slow glycolysis. Exercises for this system include those which last six seconds to two minutes such as squats, the bench press, moderate distance rowing, and so on.

- The Oxidative System. This is used in long distance activities and aerobic workouts such as marathon running. It is used typically for burning fat and its work is conducted at the end of or in a separate workout.

TABLE 1. Courtesy of the National Strength and Conditioning Association3

Exercises

Olympics Lifts

Olympic lifts are very beneficial to developing explosive power. In the fire service, our jobs require a great deal of power for circumstances such as forcing a door, self-rescue, or rescuing a down firefighter, among many others. These lifts are very high-speed and explosive and should be done under the supervision of an experienced coach to ensure quality technique. Power cleans, snatches, and clean-and-jerks are the most prevalent exercises prescribed here. Technique is of utmost importance when performing Olympic exercises. You can also use kettlebells to perform kettlebell swings and snatches.

RELATED: Ponder: Stop Waiting For The Spark ‖ Krueger: Four-Part Harmony, Part 2 ‖ Kerrigan and Moss on Improving Your Fireground Performance

Compound Lifts

As a basis for all programs, incorporate compound lifts into every workout to build overall strength. Three main exercises which are going to be critical to build tactical strength. Tactical strength coach Matt Wenning has suggested as a general guideline that max strength goals for tactical athletes needs to be two to 2½ times their bodyweight for dead lifts and 1½ times their bodyweight for bench presses. He also stated that when we increase our max strength, it increases our ability for awkward strength, which we encounter when lifting heavy patient in compromised positions. Wenning also suggests that strength needs to varied as well as transferable in the environment we operate.4

Squats are the gold standard in strength training. Mark Rippetoe stated in his book Starting Strength that, “[squats]…most critical aspect of human movement from the perspective of athletic performance…Simply no other exercise, and certainly no machine, that produces the level of central nervous system activity, improved balance and coordination, skeletal loading and bone density enhancement, muscular stimulation and growth, connective tissue stress and strength… than the correctly performed full squat.”5

Firefighters are required to wear heavy amounts of equipment, climb stairs, and then perform assigned duties. If we can build our lower body strength, we are going to be able to perform these tasks with greater ease and reduce our exhaustion. Rotate a variation of squats often to ensure total development of all lower body muscles. This will alter the stimuli in different muscles for improved overall strength. Different squat techniques include high and low bar, front, Zercher, Frankenstein, cambered bar, the box squat, the belt squat, and so on. The variations are numerous and should all be used.

The next exercise is the dead lift. The number-one injury in the fire service is the back injury. We are required to lift heavy patients, wear a self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA), and move in compromising positions. Our posterior chain is especially important to limit these injuries. If we examine the basic movements we perform each day while on the job, much of our movements are pulling-type movements. When performed correctly, the dead lift can improve overall lower body strength. Again, there are many variations which should be rotated often for full benefit. Sumo and Conventional deadlift will be the most common.6 Wenning also states that sumo dead lifts are much more beneficial to tactical athletes because of the resultant increased glute activation and development of the posterior chain.

The final exercise is the overhead press. This may be surprising to some, but the overhead press is superior to the bench press because of the types of movements firefighters perform. During normal circumstances, you are never pressing something with your back on a stable object. The overhead press is much more functional and relatable to our profession, weather pulling ceiling or pushing a cot, your shoulder will aid in the movement because of the weight transfer from the upper body through the feet. The overhead press is the best assessment of upper body strength. Increasing your shoulder strength will also aid you in overcoming the stress of wearing an SCBA cylinder for an extended period by building the musculature of the shoulder structures.

Accessory Lifts

In addition to your primary exercise, it is essential to select accessory exercises to full develop your muscular strength. Typically, selecting four to six accessory exercises will be ideal. To further help overall development, it is important to select a variety of movements, especially those which are personal weaknesses. The movements to select from include squats, hinges, lunges, rotationals, and the pull-push and are referred to as the functional movements. The focus for firefighters needs to be pulling movements because their job involves many pulling tasks such as pulling hose, ceilings, and cots.

Core

One of the most important aspects of strength training is core strength and stability. This is many times neglected or train in the wrong manner. Firefighters sustain a high rate of back injuries which accounts for most work-related injuries in the fire service. Core strength is the base of every movement due to the stability and bracing required. To train core strength, incorporating all core muscle of the abdomen, back, glutes, and upper legs, are going to be essential for any tactical athlete. Movements which should be included in this training should be stability ball, medicine ball throws, planking, glutes bridges, and other core bracing exercises. Squats, deadlifts, and Overhead press also trains the core for bracing during powerful lifts.

Job Specific Training

General physical preparedness (GPP) refers to training your athlete or yourself to develop a general basis of overall physical fitness. This sets the basis for your strength by improving weaknesses and developing overall fitness. This will then transition into SPP. For SPP, you can begin to train to a specific cause, which includes dummy drags, hose pulls, farmer carries, and stair climbs while wearing full personal protective equipment. SPP also includes kettlebell exercises. These provide the benefit of awkward strength, which is transferable to our profession. These exercises would include the kettlebell rack carry, the kettlebell farmer carry, and the suitcase carry, to name a few.

The law of specificity suggests that, to improve at a skill or exercise, you need to perform said skill or exercise. First introduced in 1945 by Thomas DeLorme, specificity is a “training method whereby an athlete is trained in a specific manner to produce a specific adaptation or training outcome…resistance training exercises that mimic the movement patterns of the athlete’s sport.” (4)To improve our effectiveness and efficiency on the fireground, replicating the fireground movement patterns will be very essential to your program.

Strength is only one of the four foundations of tactical fitness, but it is the most vital aspect of fireground safety. In our profession, all personnel in the tactical setting need to be treated and trained as tactical athletes to perform to their greatest potential. This was a brief overview for a tactical strength program can get you started toward your goals. Always consult your physician and train under the direction of a certified coach to prevent injuries. It is important to always train with superior technique to avoid injuries. Complete these exercises only if you have a good understanding of human movement and can identify poor posture and technique.

References

- https://www.t-nation.com/training/how-to-build-posterior-chain-power.

- Starrett, K., & Cordoza, G. (2013). Becoming a Supple Leopard: The Ultimate Guide to Resolving Pain, Preventing Injury, and Optimizing Athletic Performance. Las Vegas: Victory Belt Pub.

- Baechle TR and Earle RW (2008). Essentials of strength training and conditioning (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- https://www.nsca.com/videos/conference_lectures/programming_for_tactical_populations.

- Rippetoe M and Kilgore L. (2013). Starting Strength: Basic Barbell Training (3rd ed.). Wichita Falls, TX: Aasgaard.

- https://www.nsca.com/videos/sumo_deadlift_the_base_for_tactical_strength.

Ty Wheeler is a nine-year fire service veteran and a firefighter/paramedic with Johnston-Grimes (IA) Metropolitan Fire Department. He has an associate degree in paramedicine and a bachelor’s degree in fire science administration from Waldorf University. Wheeler has received several fire service and emergency medical services certifications throughout his fire service career at the state and national level. He is a member of the Iowa Society of Fire Service Instructors and with the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA). Wheeler is also a certified strength and conditioning coach through the NSCA. He also teaches for the Iowa Fire Service Training Bureau and will soon serve as the Iowa Director of the Firefighter Cancer Support Network.