WHAT HAPPENED? INVESTIGATING FIRE DISASTERS

MANAGEMENT

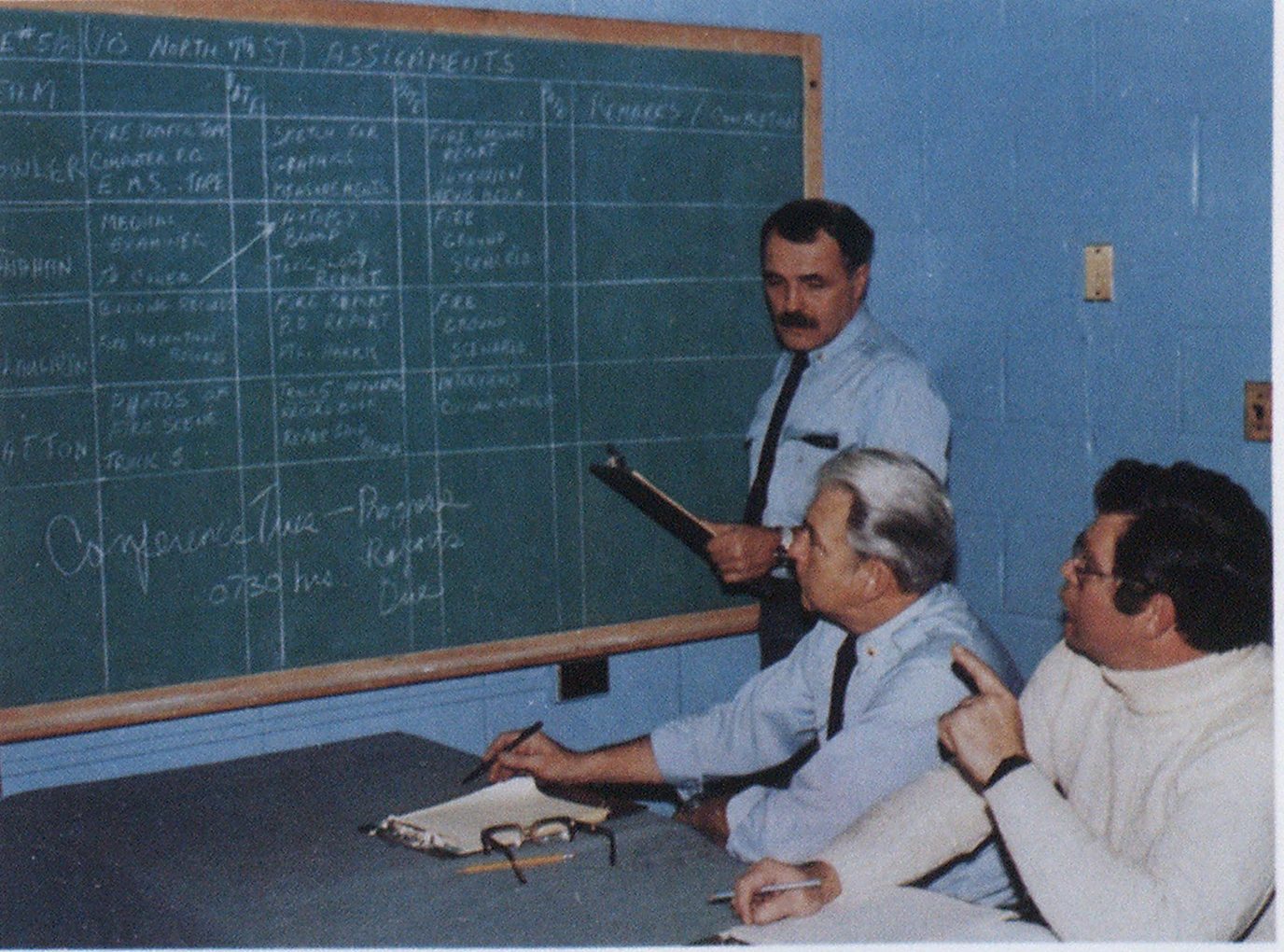

photos by Larry Hatton

News item:

ANYTOWN, April 3-A raging fire swept through an abandoned Main St. warehouse today, killing two fire fighters. They were among more than 100 fire fighters from three area departments fighting the blaze that began at 3:30 a.m.

The deaths have stunned the departments and the community. A spokesman for Chief lohn Smith said the bodies of the fire fighters were recovered at 7:45 a m. from a second floor room. They had apparently been missing on the fireground for several hours. Chief Smith has promised “a complete and thorough investigation into the events that led to the deaths of these men. We ‘re going to find out what happened so it will never happen again.”

While the above is fictional, it is true that fire fighters are going to be seriously injured and killed – and an investigation is going to be in order. Is your department prepared for a “complete and thorough investigation?” Are you or your officers prepared for the dramatic role change from that of a fireground commander to that of an investigative manager?

Fire departments have another responsibility beyond responding to emergency situations. That is investigating major fire disasters in order to determine not only the origin and cause also, and perhaps more important, to prevent similar incidents in the future. Although the primary goal of such an inquiry concerns the safety of the public, one of the most overlooked facets is that of self-examination of the performance of emergency services, especially after a fire fighter death or serious injury. In other words, can incidents of this type be fought in the future in a more efficient and productive manner so as to minimize injuries to fire fighters.

Very few fire departments maintain a professional and effective disaster investigation management plan. The common practices are to use boards of inquiry, the arson investigating services maintained by fire and police departments, or to create special investigating units generally headed by a ranking officer of the fire department.

Staffing of these units is usually accomplished by assigning personnel with extensive fireground experience — who have limited experience as investigation managers of major incidents.

Supervising the interviews of dozens of witnesses, researching response and historical records, properly handling evidence and exhibits along legal guidelines, determining the need and usage of specialized witnesses, using the sophisticated techniques of fireground scenario reenactment, and finally the publishing of an accurate report that will stand up to challenge places tremendous demand on the disaster investigation manager. This capability is generally not developed because budgetary priorities are almost always directed at the basic resources of the fire service: manpower and fire fighting equipment The major thrust of the fire service is to develop its resources to maximize its lifesaving and extinguishing effort. Selling the cost-effectiveness of developing a professional in-house investigative capability is very difficult, indeed.

It is usually only after a major disaster occurs resulting in the multiple deaths of citizens or fire fighters that departments recognize their deficiencies in this area The problem becomes manifest when fire officers are called to testify and must justify their investigative reports in the ensuing lawsuits that inevitably arise out of these incidents. Local governments usually share the burden of high monetary awards with underwriters and insurance carriers.

The solution lies in developing — beforehand—a disaster investigation manageent plan that will be implemented as soon as possible after disaster strikes.

All the investigations, regardless of purpose, have as a basis the gathering of information and a subsequent evaluation and presentation. The methodology suggested in this text is designed to give investigating fire officers an awareness of the problems they will encounter, as well as some of the pitfalls that must be avoided. The primary objective of developing investigative skills is to give command level officers tools that will enable them to develop an exact picture of what happened. Only then can a proper assessment of fire fighting activities be made with a critical view toward safety in future operations.

Fire departments should have a disaster management plan in place before an incident occurs. This will allow rapid implementation of such a plan when that disaster strikes A cadre of command-level officers should be created to receive specialized training in the tactics of managing disaster investigations Other officers would be trained in the use of investigative tools such as the interviewing process, marking and identification of exhibits, and case folder management Investigation pitfalls should be pointed out so that the final product of the inquiry is an objective document that will stand up in a legal proceeding. The combination of individuals who have a high degree of fire attack skills coupled with a solid grasp of investigative tactics is a formidable one. In order to maintain a high degree of objectivity, the head of the investigative team should not be an individual who was actually involved in the incident or fire.

The implementation of the disaster management plan is usually the first step in restoring a degree of normalcy to a fire department that has been struck by a traumatic incident. In addition, it demonstrates to the public and fire fighters a professional commitment to obtain all relevant information concerning the tragedy.

Organizing an investigation

The first step that a manager in a fire disaster should take is safeguarding evidence by gathering all pertinent records. Documents should be broken down into the following separate areas:

- Response records, including fire reports, policy reports, ambulance and hospital records, medical examiner or coroner records, fire marshal reports, lists of emergency personnel, newspaper and media accounts, fire and police communications tapes, and photos from any source.

- Historical records, including building records, all enforcement records, highways or traffic department (if applicable) equipment manufacturers, association records, e g., Cordage Institute, and department records.

The second step (probably simultaneously with the first) is to determine the physical location of evidence or exhibits. An individual should be sent to ensure that the exhibits are properly marked and secured. This individual should be conscious of the rules of evidence and have a working knowledge in the preservation of physical evidence. The most efficient method is to have all the exhibits and evidence brought to a location where the investigation team will have control and access to them. The scene of the accident must be safeguarded and preserved as soon as fire fighting operations permit.

Assembling the team

The objective of this process is to obtain an investigative staff capability equal to the complexity of the incident. This will vary from incident to incident and would be governed by factors such as the number of persons to be interviewed, the amount of physical evidence to be examined, the number and lengths of reports to be reviewed, and the nature of the incident. Obviously, a disaster such as a building collapse in which there are multiple deaths of fire fighters would require a larger and more sophisticated team than a vehicular accident which results in death or serious injury to one fire fighter.

After assembling an initial team there are several steps to be taken before embarking into a more active phase. First, have the team read all existing response reports, from the initial fire reports to media accounts of the incident. Everyone on the team has to become familiar with the known or perceived fact pattern and obtain a “feel” for the investigation. The investigation manager should instruct all team members not to develop preconceived notions about what happened but to keep open and objective frame of mind. Be aware that there is going to be an overwhelming amount of speculation and rumor after a disaster.

After reviewing all of the response data the team, under the guidance of the disaster investigation manager, must identify critical areas requiring intense investigation. In other words, what questions are we seeking to answer? Critical areas will be under constant review by the team and can be amended as more facts become available.

At this point, the investigative team is going to have to make a determination of its need for expert consultants, such as a civil engineer, in the case of a building collapse, a specialist in chemical analysis or equipment testing or an expert in fireground scenario reenactment.

The investigation manager will also have to assign different members of the team to specific operational functions of the incident. This is done so that an in-house expert is developed in each critical area of the investigation. It may be done chronologically by location or by certain specialized functions, such as ladder and ventilation or engine company operations. This should not inhibit the sharing of developments in the investigation with all the team members. It is also important to keep all the outside experts informed of all the investigative facts as they are developing.

Conduct of the investigation

The actual active phase of the inquiry will involve many processes. The interviewing and taking of statements from different classifications of witnesses has to be well organized. Case folder management and the development of investigative checklists will be essential tools for the investigation manager. Outside witnesses and civilian participants of the disaster will have to be identified and located and then questioned thoroughly.

The most important tactic an investigative team employs will probably be the disaster fireground scenario reenactment. This process is the determination of the chronological sequence of events that occurred beginning with the arrival of the initial responding units, the events that led to the actual critical accident or incident and, of course, the immediate aftermath. This should be performed by fire officers who have had an exposure to this very detailed and exacting method. Accurate statements will have to be taken from responding fire fighters. The intent is to establish time references so that an evolving pattern of events becomes clear. The successful use of this process will prove to be an invaluable aid for fire chiefs planning future operations.

All of the physical exhibits and evidence will have to be reviewed and, where necessary, have specialized tests performed on them. This review will have to be integrated into the statements of responding fire fighters as well as those of any outside witness.

The fire disaster report

A standardized format should be developed for all fire disaster investigation reports. This will allow for an easier exchange of information between fire departments. It also will facilitate the training of fire officers who will be conducting and subsequently writing the report.

After a tragic incident occurs, almost everyone hearing or reading about it will be able to relate ‘what” happened generally However, an investigative agency must be capable of answering in detail “how” and “why” it took place. Only after the “how” and “why” are known will a similar tragedy be avoided.

An untrained investigator will sometimes determine that the incident had only one obvious cause. More thorough investigative techniques will usually reveal that more than one cause led to the incident.

A professionally trained investigative team will make a valuable contribution to the overall firematic effort by providing accurate data to fire departments so that death and serious injury to fire fighters can be minimized.

Investigative Research Ltd. offers an intensive three-day course in managing fire disaster investigations, as well as a complete line of investigative services should disaster strike. For further information contact Edward Siedlick, Investigative Research Associates, Ltd., 51 East 42 St., Suite 417, New York, New York 10017, (212)867-0090

Ed Siedlick was chief investigator at the 1978 fire in Syracuse, N. Y, in which four fire fighters were killed He has been involved in numerous other fire department accident investigations Carlo Andersen is a supervising investigative officer with the fire department s Division of Safety.

Suggested Format for Investigation Reports

- Summary of Events

This is a brief account of the principal events that occurred and a lead-in to the main body of the investigative report.

- Background of the Investigation

This is a basic description of everything that occurred before the event or incident. This includes a thorough description of the building or the scene, as well as any enforcement history such as results of inspections, repairs, alterations, etc. This section should also include a description of specialized equipment if it is pertinent to the matter under inquiry. It might include apparatus, rescue equipment, tools, etc.

- The Disaster

A brief and accurate description of the cause, location and spread of the fire, nature of the explosion or type of accident. Fire marshals can usually provide the necessary information in this section.

- The Response (Fire Fighting, Rescue)

This section should commence with the discovery of the fire and the initial response of the emergency services concerned. It will list the apparatus and contain the names and duties of those fire fighters who responded. This section should also include other pertinent departments or services summoned to the disaster scene for any reason.

An intricate and detailed account of the developing scenario should follow leading up to critical operations, This is the essence of the report.

- Findings

This is the section that will require an analysis of what actually happened at the disaster. It will answer the hard questions that the fire department and the public want to know. It will serve as a basis for command fire officers to possibly change or revise procedures or to modify or utilize specialized equipment in a different manner.

- Appendix

Every investigative report should contain an appendix so that exhibits, photographs and pertinent records can be shown. The appendix is the foundation upon which the report rests. This section should be systematically and clearly organized with a concise table of contents.