‘We Don’t Have Any Air’… The Story Of BART Fire 136 Feet Under Bay

“The walkway all the way down is charged with smoke. We’re stranded down here. We don’t have any air.”

Lieutenant Wayne Schuette of the Oakland, Calif. Fire Department was talking into his hand phone, jacked into a communications circuit. He and nine other fire fighters were inside the Transbay Tube, 136 feet below the surface of San Francisco Bay and more than half a mile from their point of entry. The smoke was so thick their light beams could not penetrate more than one or two feet. The group was separated and disoriented. The supply in their 30-minute MSA oxygen breathing apparatus was depleted.

Nine of these men would make it out alive but Oakland Lieutenant William Elliott, looking forward to his retirement dinner just a few months away, would die 30 minutes after reaching a nearby hospital.

Transbay Tube design

The Transbay Tube is part of the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit System (BART) connecting Oakland and San Francisco. The east-west tube consists of three independent 3.6-milelong tubes lying side by side, sharing common inside walls, roof and base. The bore on the north side handles eastbound (Oakland) trains while San Francisco-bound trains use the south bore. Between these two bores is an 8-foot-wide gallery with doors, staggered from wall to wall, opening into the train bores. These doors, on each side of the gallery, are spaced approximately 333 feet apart.

The gallery is designed as an access and rescue passage. It is also used to house some of the massive electrical equipment used to operate the BART system. Fenced, rectangular storage areas for this equipment extend as much as two-thirds of the way into the gallery at irregular intervals.

Last Jan. 17 at 6:05 p.m., BART Train 117 entered the eastbound bore on the Oakland side, headed for San Francisco. At 6:06, the train operator reported “a bad overload and fire” to BART central control. He brought the train to a stop approximately one mile into the tube but could not give an exact location because of dense smoke enveloping the train.

Light smoke was immediately evident in all seven train cars. The operator and a chance passenger, BART Supervisor Paul Gravelle, herded the 40 passengers to the front two cars, keeping them there until rescue units arrived. If the train had been going in the opposite direction with the evening commuters from San Francisco, the passenger load could have been as many as 2000.

Confusion and misinformation delayed fire department response. It was 6:23 p.m. when Oakland Engine 9 and Truck 1 arrived at the easternmost ventilation shaft leading into the Transbay Tube gallery.

The surface commander, Battalion Chief George W. Gray, instructed the men of Truck 1 and Engine 9 to don masks (MSA 30-minute oxygen demand units), enter the gallery through the ventilation shaft and proceed toward the burning train. They were to keep in contact with Gray through a phone circuit with jacks and receivers along the gallery walls. As soon as Gray was given the exact location of the fire he would notify them.

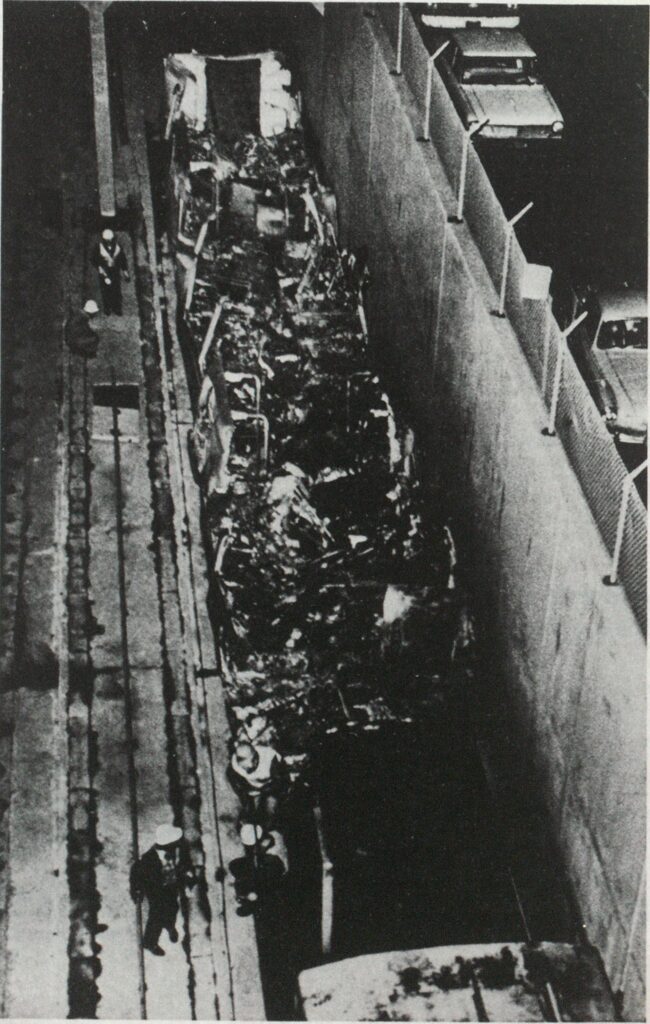

Wide World Photos

Fire fighters enter tube

Truck 1, under Elliott, consisted of four fire fighters while Engine 9, under Schuette, consisted of one engineer and two hosemen. Gray’s aide, George Kastanos, accompanied the group. When these men entered the Oakland vent structure, each company carried one resuscitator and one l 1/2-inch hose back pack. Truck 1 also brought a gasoline-powered circular saw.

At the same time, nine other Oakland fire fighters, commanded by Assistant Chief Robert McGue, entered the burning train’s bore and proceeded to the scene with two BART police officers aboard another BART train. All members of this party had 30-minute MSA masks and carried 1 ½ -inch hose packs. On arrival, they reported smoke and flame visible in the rear car of Train 117.

Gray, the surface commander, attempted to contact San Francisco fire units he believed were standing by at the San Francisco end of the tube only to find San Francisco had not yet been asked to respond. It was now 6:30 p.m., 24 minutes after the fire was first reported to BART central. Gray requested a San Francisco Fire Department response.

Smoke in gallery

Inside the gallery, the men of Truck 1 and Engine 9 were 0.2 mile in from the vent opening. Elliott reported smoke in the gallery and advised Gray by phone that they still needed information on the fire location.

At the scene of the fire, fire fighters arriving by train from Oakland found it impossible to walk to the front end of the burning train using the platform inside the bore. Instead, they entered the gallery through a door behind the burning coaches and ran 333 feet to the next door, which opened beside the front two cars where the passengers were waiting for rescue.

Fire fighters entering the train told the passengers, “be calm, come to the front of the car, a firemen will take your hand and guide you down the step to the platform.” Fire fighters outside the train led the passengers to a handrail, repeating, “Follow the rail to safety,” over and over again. Pausing occasionally to share oxygen from their masks with some of the passengers.

The smoke continued to press in on the rescue operation, becoming more and more dense. Some of the passengers started to panic, yelling at firemen “Get me out of here,” “Help,” and “I can’t make it.” Captain Robert Coombs, supervising evacuation from the train, noticed the oxygen-sharing with passengers was slowing the entire operation and ordered the practice stopped. He urged his men to speed the movement of people across the gallery and into the already crowded evacuation train.

Photo by Photoforce

By this time, the smoke and toxic fumes from the burning cars and their polyurethane seats had become unbearable to anyone without a mask. Four or five passengers were still on the train, but, badly frightened. They refused to leave the coach, forcing fire fighters to assist them out individually.

After everyone was evacuated, Coombs and Hoseman John Connelly entered the smoke-filled car and made a seat by seat search with their hands to make sure no one was left inside. Another fire fighter, Donald Olsen, made a final check of the platform area for remaining passengers. None was found.

In an official interview following the ordeal, Coombs said if his rescue unit had arrived three to five minutes later, “We would have had a major catastrophe … we would have lost them (passengers.”

Train creates windstorm

With all the passengers safely aboard, the rescue train, the fire fighters paused to catch their breath and reorganize themselves for possible fire fighting assignments. Suddenly, the evacuation train pulled out, accelerating to 100 mph in under 35 seconds. Suction in the wake of the departing train created a momentary windstorm that rushed through the gallery and the gallery door at over 100 mph, knocking several fire fighters to the ground. Fortunately, no one was hurt seriously.

With the passenger rescue completed, his men’s oxygen almost depleted and a lack of operational communications to the surface, Coombs noted that the gallery back toward Oakland was now filled with dense black smoke, but the passage to San Francisco, although hazy, appeared bearable. The fire fighters started the 2.7-mile walk toward San Francisco and open air. The time was 7:00 p.m.

When the fire rescue operations were just getting under way, the men from Truck 1 and Engine 9 were advancing farther into the gallery, having now obtained the burning train’s location. After walking forward for about 15 minutes, the group started to encounter heavy smoke, which grew thicker and darker as they advanced. Schuette and Elliott decided to have everyone put their mask facepieces on. Schuette’s watch showed 6:45. If they did not reach the fire by 7:00 p.m., they would turn and go back.

Human chain formed

After moving onward for a few minutes it became so dark the group slowed to almost a standstill. It was time to turn hack.

The two officers formed their men into a single line with Schuette in the lead. Each man grabbed the man in front of him, forming a human chain.

Visibility, with the use of hand lights, was less than two feet. The men rubbed along the left wall, using it as a reference point. Alt hough the pace was slow, they felt they would be clearing the smoke at any minute. What they could not know was the smoke, pouring into the gallery from the doors opened for the train rescue operation, was moving through the gallery at a much faster speed than they were.

Several times the fire fighters encountered obstructions along the wall, causing the group to jam up and stumble. As they started up a short ramp, the men lost their hand-to-belt contact and started to separate from each other. Chris Heath and another fire fighter saw that Elliott was having difficulty with his oxygen supply and they stayed with him until their tanks emptied. Heath started to move forward but collapsed a short distance away.

Confusion led to disorientation and then to near panic inside the smokefilled gallery. Schuette, now experiencing breathing difficulties himself, collided with Fire Fighter A1 Nero, who was trying to assist Elliott. Schuette attempted to help Nero with Elliott but to no avail. They were unable to make any forward progress as Nero also ran out of oxygen.

Schuette told Nero to stay low and went back down the gallery to find a phone box. Locating one, he lifted the receiver, but no one answered. Schuette then plugged his handset into a jack near the phone box and reached Gray.

At about the same time, three of the fire fighters from Engine 9 reached the vent shaft and climbed out. They informed Gray that urgent help was needed inside the gallery. Gray dispatched rescue teams down the gallery and down the eastbound train bore.

Two reach safety

After leaving the phone, Schuette heard rescue party members coming down the bore. He crawled toward the sound and reached the safety of the bore, an area he previously believed filled with as much or more smoke than the gallery. Nero, unable to do anything further for Elliott, managed to reach the vent structure.

Another fire fighter, Gary Gerner, proceeded up the gallery until his oxygen tank ran out. He thought of removing the breathing equipment and running as far ahead as he could in an attempt to get out of the murderous smoke. As he reached to unfasten the oxygen tank on his back, he heard Kastanos, Gray’s aide, yell out. Kastanos had opened one of the bore doors and found the track area relatively clear of smoke.

Once outside the gallery, Gerner removed his mask, took a deep breath and ran back inside as far as he could to check the floor for fellow fire fighters. He returned to the door for another gasp of fresh air and went back inside, checking in the other direction. Gerner kept this up at several gallery doors until he heard other rescuers coming into the area. Gerner then reentered the gallery to assist Fire Fighter David Chew, a member of the rescue party, in reviving and removing Chris Heath from the gallery.

Gives CPR to officer

When other fire fighters, a few moments later, pulled Elliott out of the gallery, Gerner was there to give CPR to his stricken supervisor. Later, Gerner and another member of Truck 1 walked out of the bore and were taken to a hospital for smoke inhalation treatment.

When Gray, the surface commander, first became aware that he had men down inside the gallery, he ordered the men of Oakland Engine 1, under Captain Lauren Dewey, to attempt a rescue by going through the gallery itself and he ordered other companies into the eastbound train bore.

Dewey and Fire Fighters Chew and Ken Sumner entered the vent structure, carrying a resuscitator and two spare oxygen bottles. They climbed down the ladder inside the 4 X 4-foot shaft to track level and proceeded down the gallery. At 150 to 200 yards in, they found two fire fighters, covered by a thick coat of black soot, standing in front of a wall of dark smoke yelling for the rescue party to hurry because at least two men were down inside the smoke-filled gallery behind them.

Breathing restored

Using the walls on each side as a guide, the three men proceeded down the gallery another 1400 feet, where they found the prostrate form of Heath wearing only his oxygen cylinder. Heath was not breathing. Oxygen was administered immediately from the resuscitator and, after about 15 seconds, Heath started to breathe on his own. While additional oxygen was given to Heath inside the gallery, other rescue personnel arrived to lend assistance.

Chew and another rescue fire fighter, Dennis Holmes, proceeded down the gallery another 500 to 600 feet and found Elliott on the floor. Although the oxygen in both their tanks was depleted, they remained with Elliott, calling out for assistance.

Dewey and Sumner answered their cry and helped remove Elliott from the gallery to the bore, where CPR was started immediately. The rescue teams continued to search the gallery area until all personnel were accounted for.

In the meantime, halfway between the fire and the exit on the San Francisco end of the Tube, the outbound group of Oakland fire fighters who performed the passenger evacuation met members of the San Francisco Fire Department. They passed on what information they could to the inbound crew and were told San Francisco was proceeding to the fire on foot and by train. All those responding had Scott 30-minute Air Paks and carried extra air cylinders.

The BART train carrying San Francisco personnel to the fire made it about 1 ½ miles into the tube and lost power, forcing the truck, engine and rescue companies on board to travel the last mile on foot.

Once at the scene and inside the gallery, Battalion Chiefs E. Anderson and William Roberts deployed the men, ordering large hose lines connected to a standpipe in the westbound bore and strung across the gallery.

Search for train

Captain C. Ryan of San Francisco Rescue and his men were instructed to start opening gallery doors to the eastbound bore to locate the burning train. Once the train’s position was established, the 2 ½-inch hose lines were stretched through three gallery doors, wyed off to 1 1/2-inch lines and then charged.

Roberts contacted the Oakland Fire Department by phone to check the status of the power to the 1000-volt third rail in the eastbound bore. After a 45-minute wait, BART central reported the power off and grounded. Fire supression actions were immediately initiated.

Heat from the fire was so intense that although hosemen were protected by fog from a second line, they required relief every five minutes. The high temperature caused considerable spalling of the concrete ceiling in the tube and pieces weighing up to 40 pounds dropped into the burning cars.

It took a total of 42 fire fighters working inside the tube more than 3 ½ hours to bring the fire under control The time was now 1:31 a.m.

Investigation started

The California Public Utilities Commission ordered an immediate closing of the BART Transbay Tube and started an investigation which uniquely provided that the tube would not reopen until new safety requirements drawn up by the San Francisco and Oakland fire chiefs were met and approved by the two chiefs.

The Transbay Tube was closed for 11 weeks.

On March 5, Oakland Fire Chief William Moore, chairman of the board of inquiry submitted the board’s report, over 180 pages of description, analysis, charts, diagrams and recommendations, to C.K. Bernard, BART general manager.

An important part of that report, “Emergency Equipment and Procedures,” dealt with the breathing equipment of Oakland and San Francisco fire fighters.

Equipment used

In part, that report read: “Both the Oakland and San Francisco Fire Departments are equipped with breathing equipment of one-half hour duration.

“During the BART fire the San Francisco Fire Department was using Scott Air-Paks which supply air to the user while the Oakland Fire Department was using MSA packs which supply oxygen. Both types of breathing equipment operate on the same general principle, although the San Francisco apparatus was equipped with lowpressure alarms while the Oakland Fire Department equipment did not have this safety feature…

“Breathing apparatus of one-half hour duration is not sufficient for protection of personnel working in the Transbay Tube under emergency conditions. The service period of this apparatus is also too short if extended rescue or fire fighting activities are necessary. An example, the captain of San Francisco’s Rescue Company One had to replace his air cylinder three times during the course of the fire.

Lack of reserve cited

“The Oakland fire fighters ran out of air while they were still a considerable distance from safety, and would have had no reserve left if they had reached the scene of the fire and were required to perform rescue or fire supression activities.

“During the interviews with the Oakland fire fighters who were trapped in the gallery, it was their opinion that even if they had reserve cylinders of oxygen, they probably would have had great difficulty in replacing them in the dense smoke.

“The absence of low-pressure alarms in the breathing apparatus were also detrimental to the safety of the Oakland fire fighters. Low-pressure alarms sound a warning when there is approximately five minutes of service left in the supply cylinder and give the wearer an opportunity to evaluate alternative actions.

“Without this safety feature, there is no warning, only an immediate absence of breathable air, and the facepiece must be removed. There is no time to evaluate choices and make a reasoned decision…”

Need in other situations

This was not the first time such observations have been made about the 30-minute breathing apparatus, not just for subterranian passage fires but for use in high-rise buildings, dock and ship fires and large warehouse fires. In fact, BART previously ordered 45 four-hour oxygen breathing units from BioMarine Industries, Inc., of Malvern, Pa. The BioMarine units, however, still required testing and approval by the National Institute for Safety and Health (NIOSH) before they could be used for fire fighting, a process which could take several months.

A study of long-range breathing apparatus found one unit on the market currently accepted hy NIOSH. It was the BG174A manufactured by the Draeger Corporation in Germany and available through BWS Distributors, Inc., of Santa Rosa, Calif., Draeger’s national distributor.

Eighteen Draeger BGl74As (all that were currently available throughout the United States and Canada) were immediately shipped to BART. Nine units were then given to the San Francisco Fire Department and nine to the Oakland Fire Department.

Training started

Classes in the equipment’s use were started at each department’s training center with the Draeger Corporation supplying qualified instructors.

Kenneth Kannegaard, a mine safety instructor for the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) worked with Oakland lire fighters, and Samuel Loy, vice president for BWS Distributors, set up the San Francisco program.

Each training session lasted three days and provided 20 hours of indoctrination for senior officers and rescue personnel. In the three sessions given in each department, 54 fire personnel were trained in the use of the Draeger BG174A.

Two other cities bordering Oakland, Berkeley and Orinda, also have underground BART facilities and were included in the training program.

BART pays for units

When the remaining 27 units on order from Draeger arrived in early May, Chief Moore of Oakland and Chief Andrew Casper of San Francisco gave immediate attention to additional training programs for their fire fighters. Each department will maintain the units, but maintenance costs and the $2300 price tag for each of the units will be paid by BART. The fire departments also have the option of using the BGl74As in fighting high-rise, ship, dock and warehouse fires.

The Draeger BG174A is described by the designer as a closed-circuit, oxygen, self-contained, four-hour apparatus weighing approximately 35 pounds. Designed to be worn on the user’s back, it has a rigid aluminum cover protecting the internal parts of the breathing unit.

After the initial training period, the trainees now serving as instructors in their departments became aware of a few areas of concern that developed during use of the BG174A in fighting fires.

This Draeger equipment has been used by European and Canadian fire departments and in mining operations throughout the world for many years. Ideally, the equipment is used under hazardous conditions for one to two hours, allowing ample reserve in case of an unexpected emergency.

Warning device installed

Based on this type of usage, a lowpressure warning device was not deemed necessary by either the manufacturer or the users. NIOSH regulations, however, require a warning whistle, necessitationg a modification of the BG174A and the addition of a four-valve warning system. Since taking delivery of the initial 18 units, both Oakland and San Francisco have experienced whistle malfunctions and leakage in the warning system valves.

San Francisco, which carries the BG174A on its fire apparatus, also encountered valve leakage in other parts of the equipment, apparently caused by road and truck vibration.

Unfortunately, the fire departments just kept making repairs, replacing parts and becoming more and more frustrated with the breathing apparatus, but they did not notify the manufacturer.

Designer flies to U.S.

The Draeger Corporation, finally made aware of the problem by Photoforce, a multifaceted photo-journalistic and investigative reporting organization in San Francisco, arranged for the equipment’s designer, Ernst Warncke, to fly from Germany. Warncke, in the company of National Draeger Inc., Pittsburgh, James R. Ellison and R.T. Barton from BWS Distributors, Inc., met with representatives of the four fire departments (San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley and Orinda). As a result, Draeger will be conducting additional vibration and stress tests on the BG174A to correct the problems.

Four-hour breathing apparatus is not designed, as are the 30-minute units, to be rushed to a fire, thrown on someone’s back and put into immediate use.

There is a checkout procedure recommended by the manufacturer that should be completed just before each use. This takes up to five minutes and makes the four-hour apparatus a supplemental fire fighting tool and not a total replacement for its much simpler 30-minute cousin.

Suggested use

Fire fighters using the half-hour equipment can make initial entry, start fire supression and rescue operations and direct personnel with four-hour gear to time-consuming operations where lengthy exposure to smoke or toxic fumes is anticipated.

Some supervisory personnel in the Oakland and Sna Francisco Fire Departments have expressed dissatisfaction with the checkout procedure, feeling it is too involved. They are hopeful minor modifications or new product design will eliminate the need for onthe-scene testing.

As with any new equipment, acceptance of four-hour breathing apparatus will take time, training and some experimentation to determine its most effective use in specific situations.