BY JACK LOPEZ AND JIM MARKLEY

As experienced firefighters retire in larger numbers, many departments have faced and will continue to face the challenge of fielding a younger leadership force that lacks the experience used to build the mental database of prototypical responses to deal effectively with the situations they will face. Where and when will they gain the experiences on which to quickly base their size-up and risk assessments? How will they learn to develop effective incident action plans based on the circumstances? When will they practice maintaining situational awareness?

If people learn best through active learning—i.e., by doing—then you have some measure of control through the decisions that you make while learning. We can gain experiential or experienced-based knowledge in the fire service through our responses to realistic incidents; making decisions under time pressures; and experiencing the consequences of those decisions without burning down structures, risking lives, or consuming resources. So, how can this be accomplished? With wargaming.

Wargaming can be a key experimental learning tool to augment traditional firefighter training methods to help build the future incident commanders (ICs) our communities need.

The following scenario demonstrates our point with a possible situation that limited-experienced firefighters could face in any city or town across the United States.

Anytown, USA, September in the Near Future: 0254 Hours

With the combination of Engine 6’s blaring siren and the chauffeur’s overuse of the air horn, Lieutenant Erin Rodriguez found it difficult to discern the garbled updates from Fire Dispatch over the rig’s radio. She silently cursed the dispatcher on duty, who she thought was always too soft-spoken for moments like this. The young lieutenant feared that her two crew mates would notice her growing anxiety. After all, it was not too long ago that she was riding in the back seat as a firefighter as well as taking turns at the driver’s seat with her previous crew. This early September morning, however, she was the officer in charge of an engine company on its way to a reported structure fire with trapped occupants.

(1) U.S. Army War College students play a high operational wargame. The game is Joint Overmatch Euro-Atlantic. (Photos by Jim Markley.)

Her dedication, hard work, and intelligence had paid off in securing a top position on the promotional exam results, beating out more than 80 other firefighters. A perfect storm of department budget cuts, staffing shortages, firehouse closings, and the unexpected mass retirement of experienced officers and senior firefighters put her in the right seat of the apparatus much earlier than expected. Seeking out advice and guidance from officers and senior firefighters paid dividends for her professional growth and skills, but those opportunities were short-lived because of retirements.

She has been a firefighter for six years now, the last two weeks as the officer of Engine 6, after completing basic company officer training. The chauffeur and “senior” firefighter, Sean Murphy, has less than 10 years of experience. Rounding out the rest of the crew on the nozzle was Firefighter Dwayne Beltran, with less than two years on the job. Combined, they had less experience than any single one of the firefighters or officers who retired. They liked to joke that they had a total of almost 1,000 weeks of experience (the higher number sounded more impressive).

This was the second fire reported in the midtown district this shift, and dawn was still at least another three hours away. The first fire call came in shortly after 0200 hours, a working fire with trapped occupants in a three-story, wood-frame, multiple-occupancy apartment building. That fire had already absorbed a third-alarm response and was still working. Mutual aid from the bordering town was already on the way. The off-duty deputy chief, called in to cover the rest of the city, just arrived at headquarters and would be delayed. For now, it was just Engine 6 and Ladder 3 responding to this second reported fire, with the ladder company having a greater distance to travel. It appeared that Engine 6’s three-person crew would be operating on its own for several minutes or more—a lifetime when lives were at stake at a working fire. It was now 0254 hours. This would be the lieutenant’s first fire as the initial IC.

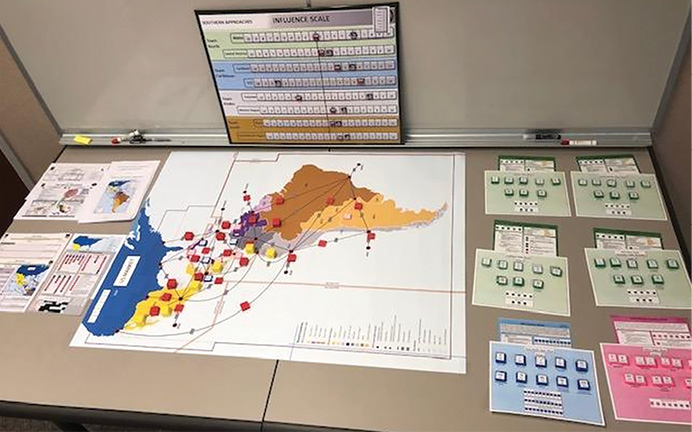

(2) “Securing Southern Approaches” is a plan development and exploration game.

As the apparatus rounded the corner of the partially smoke-obscured street, lined on both sides by two-story attached row frame houses, this new officer was preparing to make split-second life-or-death decisions—decisions that could potentially have consequences for the trapped occupants of a burning building, her crew, and other responding units. If the fire was raging in the basement of the attached two-story ordinary row house, would this officer and her two-year “veteran” crew mate on the nozzle notice the visual cues or have enough experiential knowledge to see that as a possibility? Would they manage to perform a proper size-up and risk assessment? Would they focus purely on the trapped occupants and stretch a handline through the front door, ignoring the danger of operating on the living room floor right above the fire? The crew of Engine 6 was about to engage in the most difficult fight of their young careers.

Given the limited amount of experience of the fighters in our scenario above, were this officer and crew properly prepared to make the best decisions given the circumstances? Although they certainly would have obtained the required certifications and training to enhance their knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs), were they prepared mentally for the challenges that awaited them? Were the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health five causal factors (the NIOSH 5) already starting to cast a looming shadow over their situation?1

Decision Making on the Fireground

The ability to make quick, critical decisions on the fireground while under extreme time pressure is developed over time through your collective experiences and knowledge. In 1988, the U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences commissioned the study Rapid Decision Making on the Fire Ground. The authors studied firefighting and focused on the decisions made by 26 fireground commanders from seven departments at 32 separate critical incidents. All participating officers had an average of 23 years of experience; none had less than 12.2

The result was recognition-primed decision making (RPDM), where the study found that in more than 80% of the cases, fireground commanders used their experience to directly identify the situation based on their stored knowledge of standard prototypes rather than the expected conventional time-consuming selection of one option from a set of two or more alternative courses of action. Their knowledge, perceptual cues, and goals dictated their actions at that moment. Most of the decisions these officers made were made in less than a minute; many were made in under 30 seconds.

Firefighters operate in an occupational environment that requires experiential knowledge. This environment requires that you increase your skills through experience gained by exposure to different situations. You can increase your knowledge of the science of firefighting by reading and studying. You can improve your skills through training. However, you cannot gain years of experience using these same methods and develop your operational art.

Programs like the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program and the International Association of Fire Chiefs (IAFC) National Near Miss Reporting System are great resources for researching the lessons learned from previous incidents. These reports provide a laundry list of contributing factors that led to a near miss or an unfortunate line-of-duty death (LODD).3 Although valuable, these resources lack the ability to provide a dynamic environment that allows for a group of firefighters to work together to solve the same problems that confronted the individuals in these reports. Wargames, on the other hand, do provide this sort of dynamic problem-solving environment.

Adopting wargaming is not a replacement for current training and education methods. Wargames aren’t the answer to all training shortfalls and won’t replace the value found in other experiential education methods such simulations and simulators (wargames are a form of simulation). Fireground simulator systems have been used for decades and have offered an excellent means to create simulated fire scenes to help firefighters practice scene size-ups, decision making, and building specific incidents. Although a great training tool, these simulators have a limited ability to explore human decision making, particularly in environments with incomplete and imperfect information. Simulators are also expensive to run and maintain and typically have limited availability. Wargames, in contrast, are inexpensive, generally require limited overhead in terms of the facilities personnel needed to run them, and can be used anytime there are a couple of hours of potential free time from regular firefighting duties.4

Why Wargame?

In the mid-1820s, when General Karl Von Müffling, then the Prussian Army’s chief of staff, received a demonstration of a new tool called a “wargame” (“kriegspiel” in German), he is said to have exclaimed, “It’s not a game at all. It’s training for war!” Since that time, militaries around the world have been using wargames to simulate warfare as a means of training (mostly) their officers for the challenges they will face in commanding and controlling military forces in war.5

What made that first wargame so appealing to the Prussian Army still appeals to militaries today. By moving small blocks of wood representing military units around a scale map, Prussian officers were able to experience the challenges associated with fighting a military force in space and time under varying simulated environmental conditions, in differing terrain, and against a variety of potential enemies. Today’s technology may make the original Prussian game look like child’s play, but these early wargames were highly effective in training officers to be leaders.

Wargames work by helping young officers (and the not so young, too) to increase their understanding of the complexities of warfare. Through wargames, officers and soldiers (hereafter referred to as “players”) can test assumptions and reveal the unintended consequences of decisions they make without fear of loss of life, equipment, or other resources. Wargames allow players to explore various options or courses of action in a simulated environment and learn from the mistakes they make without concern for adverse costs to their organization or others.

One attribute of wargames that distinguishes them from other forms of learning is that they require players to make decisions. Players can practice decision-making skills and put into practice what they have learned through more traditional instruction (reading, classroom instruction, and watching videos). Talking and thinking about a situation alone aren’t good enough; the player must make the decision, take the required actions, and deal with the consequences. In many ways, this requirement to decide forces leaders to think systemically about the challenges presented in the wargame. It is not enough to merely decide; the player must also try to understand the consequences of those decisions. Wargames are a safe place to fail and to learn from failure.

In a wargame, a participant can think through or talk out decisions that must be made in a split second. This ability to slow down when making important decisions gives leaders a chance to explore the range of possible decisions in greater depth, leading to better informed decisions.

Wargame players learn by deciding and doing. The lessons learned in wargames become a part of a leader’s experiences and are available for recall when needed later. Playing wargames multiple times with varying conditions and situations helps to build resilient knowledge of how to employ military capabilities in a way that contributes to the development of RPDM in wargame players.

Fight a Fire Every Day

Wargaming isn’t just a military tool anymore. It has a broader appeal to government agencies, nonprofits, and businesses that have discovered this as an effective tool for seeking strategic advantages. The secret to wargaming’s power is its ability to combine narrative storytelling, actions, and the inner workings of the human brain. In a 2011 Naval War College Review paper, professional military wargame developers and analysts reasoned that “wargaming’s transformative power works as a story-living experience that engages the human brain, and hence the human being participating in a game, in ways more akin to real-life experience than reading a novel or watching a video. By creating for its participants a synthetic experience, gaming gives them palpable and powerful insights that help them prepare better for dealing with complex and uncertain situations in the future.”6

Wargames are designated into two primary categories, educational and analytical, which can be further broken down into a number of subcategories. However, for the purpose of this article, we will focus on educational wargames that are also experiential, much like the original Prussian kriegspiel.

For firefighters, the educational wargame’s purpose is to educate its players by reinforcing learning objectives through a method of exposing students to previous near-miss or LODD incidents or possible future scenarios. Placing firefighters in environmental situations that they are likely to encounter, allowing them to make decisions, and discussing their mistakes all reinforce the knowledge they gained in the classroom or through study.7

Wargaming Methods, Models, and Tools

There is significant overlap in the underlying technologies, techniques, and methods associated with modeling and simulation (M&S), experimentation, and wargaming. However, all three are distinct in the methods they use. The often-used metaphor of a “What if?” stool that is supported by the three legs of M&S, experimentation, and wargaming helps to demonstrate the relationships.4 Using all three will help to ensure the future success of the fire service by helping to address the “What if?” questions. So, how can wargaming, as a stand-alone leg of that stool, specifically contribute?

Some examples of fire service educational/experiential wargames under development include scenario-based games that place the player in command of a fire company, using a board game format with a city map and structures. The scenario incorporates a set of problems presented at the start; the player must decide on the priority in which to address the specific problems within his company. Those decisions will affect the company’s performance as the wargame unfolds and as they respond.

Incorporating multiple players in the wargame allows simultaneous actions that would be required for a coordinated fire attack. Having multiple players in the game also means that the players must communicate their decisions to each other. The need to communicate decisions effectively to be successful in the game directly transfers to building trust among players.

Each decision and action taken has consequences. When the player decides on specific action, that action is judged as either successful or unsuccessful based on a KSA table that gives the player a probability of success. That success or failure is based on the company’s performance, which, in turn, is based on the initial decisions the player made at the start of the game to address issues with the company.

If the action is unsuccessful, consequences begin to mount, presenting the player with a greater problem to resolve or negatively impacting the environment for the other players. The players must then formulate a Plan B, a Plan C, and so on.

The actions and game timing are controlled and limited through turns. Each turn represents a specific period of elapsed time within the game to correspond with the length of time a company’s actions would normally take in a real-life incident. This also places a time pressure on each player in which to make decisions and take actions.

Using a board game-style wargame format offers many advantages. It is cheaper to acquire and run and requires no computers or additional equipment, making it easier to obtain for each firehouse or company. The act of physically moving a piece on a board requires a higher level of commitment to the action vs. a computer or simulator input. This higher level of commitment is thought to result in players being more deliberate in their thinking before taking an action compared to the simple act of “point and click” on a screen.

This is similar to a chess player holding onto his chess piece and thinking through a move before making that final commitment and letting go. Hence, players must use their imaginations, visualizing for themselves what is going on in the game environment. Visualizing and then verbalizing stimulates critical and narrative thinking. Essentially, players must conceptualize in their mind what is really going on vs. what they see.

Finally, board game-style wargames are much easier to modify or change. Conceivably, anyone who is very experienced at playing that game can make the modifications and changes on his own.

Experiential wargames can provide firefighters with needed experience that will better prepare them for these same environmental situations, reinforcing the knowledge gained through training and drills. These games are designed to convey knowledge of their roles and responsibilities. Players are responsible for their decisions and the consequences, as they would be on the actual fireground.

Firefighters can fight a synthetic fire every day in the safety of the firehouse or classroom without risking life, injury, or equipment damage. In the process, they gain valuable experience and start building on their RPDM stored knowledge much sooner than otherwise. The knowledge and experience gained help in reducing the typical mistakes that limited-experience firefighters would make, improving overall safety.

Authors’ Note: The ideas expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or views of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Endnotes

1. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), Arson Fire Kills Three Fire Fighters and Injures Four Fire Fighters Following a Floor Collapse in a Row House–Delaware, A Report from the NIOSH Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program, November 9, 2018. https://bit.ly/36P20Hz.

2. Robert Holt and George W. Lawton, Technical Review Report 796, Rapid Decision Making on the Fire Ground, Battlefield Information Systems Technical Area, Systems Research Laboratory, U.S. Army Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, Alexandria, VA, June 1988. https://bit.ly/3Htn7vy.

3. Andrew Beck, “Art and Science in the Fire Service,” Fire Engineering, August 2019. https://bit.ly/33ZYARf.

4. Ernest H. Page, Modeling and Simulation, Experimentation, and Wargaming–Assessing a Common Landscape, The MITRE Corporation, Case Number 16-2757. https://bit.ly/3CeerZf.

5. Matthew B. Caffrey Jr., On Wargaming, How Wargames Have Shaped History and How They May Shape the Future, Naval War College Press, Newport Rhode Island, 2019. https://bit.ly/3poyCOy.

6. Peter P. Perla and ED McGrady, “Why Wargaming Works,” Naval War College Review, Vol. 64, Number 3, Summer 2011. https://bit.ly/3poyCOy.

7. Peter P. Perla, The Art of Wargaming: A Guide for Professionals and Hobbyists, U.S. Naval Institute, Annapolis, MD, 1990.

JACK LOPEZ retired as a fire captain after 26 years of service with the Bayonne (NJ) Fire Department. He has been a NJ certified fire instructor, a captain and instructor on the department’s rescue company, and a member of the Hudson County Urban Area Security Initiative Metro Strike Team—USAR. He is a member of the Military Operations Research Society and has a certificate in designing tactical games. Lopez is engaged in research on the use of probabilistic modeling for simulating fire department operations, focusing on strategy and tactics.

JIM MARKLEY is a retired U.S. Army colonel and is the deputy director of the Department of Strategic Wargaming at the U.S. Army War College. Markley oversees a group of professional wargamers who develop educational wargames for the college and analytical wargames for defense organizations to understand and address national defense challenges they face in the defense of the nation.