VOLCANO!

FIRE REPORTS

The critical importance of highly-organized incident command procedures was emphasized during a volcanic eruption in Hawaii early this year. The 10-week battle with lava flows, brush fires, and lack of water supplies resulted in the greatest mutual-aid effort in Hawaii’s history.

In the first 10 weeks of 1983, the Hawaii (County) Fire Department (HFD) on the Island of Hawaii met and conquered the most severe challenge in its history —a major eruption of Kilauea Volcano, a lava flow that destroyed (in March) two residences, caused five brush fires that burned 18,000 acres and eight homes, and forced evacuation of nearly 600 other homes. And, as crews mopped up the last brush fire, other HFD members evacuated people from a beach park campground and ocean-front condominiums that were threatened by 30-foot waves pounding the shores of Hilo.

Two, and often four, of these events occurred simultaneously, severely straining HFD’s resources.

The events of those 10 weeks led to the greatest mutual-aid effort in Hawaii’s history, both in number of personnel and number of agencies involved. It was also the first time in 50 years that large numbers of fire fighters were brought from neighboring islands in response to a mutual-aid call.

Eruptions

Scientists at the U S. Geological Survey’s Hawaii Volcano Observatory had been anticipating an eruption of Kilauea, the world’s most active volcano, for almost a year. Because the science of volcanic prediction is still in its infancy, no precise information as to the time and exact location of the outbreak was available.

Lava first broke from a 300-foot-long fissure in the earth’s surface at 12:31 a m. on lanuary 3, in an area 5 miles from the nearest road. It lasted only an hour.

Eruptive activity resumed on January 5 at 11:23 a m., and by January 7 a lava flow covered more than 250 acres. The Royal Gardens subdivision, 3 miles away, lay directly in the flow’s path.

A state of emergency was declared, and a control center established in Civil Defense Emergency Operations Center in Hilo. Field command posts were set up near Royal Gardens to handle the eruption.

Hawaii County CD Administrator Harry Kim, who was in command of operations, ordered all residents of Royal Gardens to leave immediately. Kim feared not only the flow itself but also the sodium dioxide-laden volcanic fumes and the threat of brush fires that the advancing molten rock could cause. The island was in the throes of a six-month drought, having received less than 8 percent of its average rainfall.

Kim requested HFD Tankers 4 and 10 to stand by during the Royal Cardens evacuation. Chopper 1, the fire department’s helicopter, was dispatched for aerial observation.

The outpouring of lava slowed during the afternoon of Jan. 7, but geologists warned that the eruption was only in a lull Fire, police and CD officials remained on a standby alert.

Although the eruption stopped at 12:30 p.m. on Jan. 11, scientists emphasized the likelihood of further activity. Meanwhile, four geologists had found themselves virtually surrounded by the lava flow and had to be transported to safety by helicopter.

Kilauea then began a game of hide and seek that continued for the next seven weeks. The on-again, off-again eruption generated only small lava fountains and minor flows. Neither lives nor structures were endangered.

Brush fires

Then, at 11:26 a m on Feb. 15, the HFD received a telephone alarm for a brush fire in the Hawaiian Shores subdivision 15 miles from Kilauea. Engines 3, 5 and 10 and Tankers 4 and 5 were dispatched under the command of Acting Battalion Chief Dominador Coloma.

At 11:34 a m., first-due Engine 10 reported a working fire with approximately I acre involved. By 12:09 p.m. the fire had spread to 5 acres and winds were estimated at 15 to 20 mph. Requests were made for two bulldozers from private contractors, the HFD s Chopper 1 and manpower from the county’s public works department At 12:30 p.m. Coloma reported that the fire had consumed 15 to 20 acres, and he ordered a recall of off-duty HFD members.

State forestry crews, additional bulldozers, and support apparatus from the FHFD were dispatched during the next hour as the fire spread to 100 acres.

By 4 p.m, the fire had consumed 1000 acres of brush and, two hours later, 2000 acres had burned The fire was raging through heavily populated areas, forcing fire fighters to race ahead of the flames to protect one house after another, 400 in all.

Fire fighters were seriously hampered by a lack of a municipal water system. Residents depend upon rainwater catchment systems for domestic water, and since there had been almost no rain there was no water. The closest hydrants were 3 miles away. Lack of water forced fire fighters to concentrate on bulldozing firebreaks and backfiring to contain the blaze.

By the morning of Feb. 16, the 3000-acre fire was thought to be contained. However, at 11:15 a.m., it jumped the final firebreak separating the flames from homes in neighboring Hawaiian Paradise Park. Battalion Chief Apitai Akau ordered Engine 5 and Tankers 4, 5 and 10 to respond to Makuu Drive, a major street in the subdivision. HFD Chief Shozo Nagao issued a recall for all remaining off-duty fire fighters.

The following agencies were on the scene by 2 p.m.: Hawaii County CD; HFD (three engines, four tankers, Chopper 1 and four engines manned by volunteers); Hawaii County Police: two National Guard helicopters; five bulldozers from five private contractors; personnel from the State Forestry Division, Hawaii County Departments of Public Works and Parks/Recreation, and Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (one engine and an 8000-gallon tanker); Kilauea Military Camp (one tanker); and Pohakuloa Training Area (a 1000-gallon tanker). Personnel from all agencies totaled 225. Utility company workers were also on hand to disconnect their equipment if necessary.

Finally, at 4:26 a.m. on Feb. 17, Chief Akau reported that there was a firebreak around the entire area and that the subdivisions were secure. The area burned was 6575 acres. HFD members would maintain a 24-hour-per-day watch for the next month, however, as numerous hot spots flared and an occasional brand blew across the breaks.

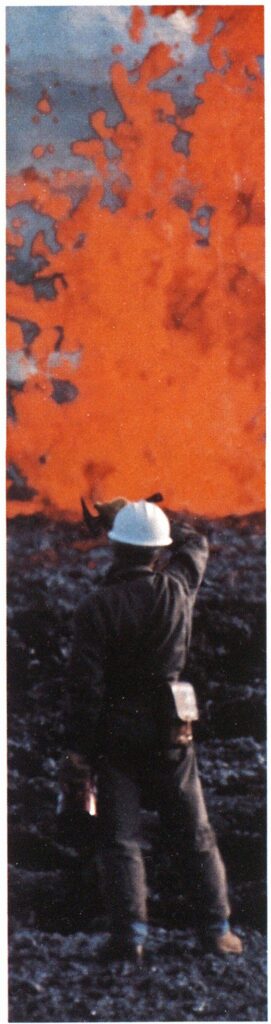

All was relatively quiet until 9:30 a.m. on Feb. 25 when Kilauea again burst into life with 100-foot-high fountains of lava.

Dr. Robert Decker of the Hawaii Volcano Observatory warned that a major eruption was occurring and that Royal Gardens subdivision was imperiled. The lava flow was 2 miles away and moving about 1 mile per day. However, lava flows are subject to the vagaries of nature and no accurate estimation could be made as to just when the river of molten rock would reach the first homes.

The HFD’s problems were just beginning. At 11:37 a.m. on Feb. 26, an alarm was received for a brush fire at the 6000foot elevation on the slopes of Mauna Loa, far above populated areas and on the opposite side of the island from Kilauea.

What may have seemed an advantage quickly turned to hardship when it was discovered that there were no trails or roads into the fire area. All equipment and personnel would have to go in by helicopter or on foot, a distance of several miles. Also, the high elevation brought with it below-freezing night temperatures, a situation that Hawaii’s fire fighters had never contended with and were not equipped for.

Battalion Chief John Ide, responding in Chopper 1, reported 1 acre of Greenwell Ranch land involved and an easterly wind of 10 pmp.

Recall of HFD personnel from Stations 6, 7 and 9 was ordered at 12:12 p.m.

The Island of Hawaii, or the “Big Island” as it is known to the residents of the 50th state, is the southernmost and largest island in the Hawaiian chain. Its 4021 square miles form the County of Hawaii with Hilo being its principal city (population 30,000).

A total of 200 career fire fighters operate 11 stations on the island. These stations are supplemented by 12 volunteer stations in rural areas, each having one pumper or a small tanker.

Mutual-aid resources are limited by the island’s isolation. The only assistance immediately available is from the military at Pohakuloa Training Area and Kilauea Military Camp, the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park and the State of Hawaii’s Forestry Division.

The fire was moving slowly compared to the Hawaiian Shores/Hawaiian Park Paradise blaze, with 50 acres being involved by 7 p.m. HFD members and Creenwell Ranch employees worked frantically to contain the fire before the inevitable morning trade winds picked up. They were unable to do so, however, and the fire ultimately burned 850 acres of ranchland and brush.

The advance of the lava flow threatening Royal Cardens had slowed but the tremendous lava outpouring from the vent had not diminished at all. Fountains were now reaching heights of 300 feet, occasionally more. CD Chief Kim alerted all agencies for rapid evacuation if conditions deteriorated.

Feb. 27 brought a turn of events that no one had really dared to think about. At 3:45 p.m., another brush fire occurred in Ainaloa subdivision less than 1 mile from the Hawaiian Shores/Hawaiian Paradise Park fire and 15 miles from the increasingly ominous Kilauea eruption. The same HFD assignment was first due at all three locations. Meanwhile, the Creenwell Ranch fire continued to burn uncontrolled also.

Engine 4 and Battalion Chief lames Higashida were dispatched to Ainaloa. “Working fire! Several acres already involved and houses dangerously threatened!” was higashida’s radio message as he approached the scene.

Within three hours, 500 acres were afire and the HFD was committed to a third simultaneous fire fighting effort, an effort that they lacked the personnel to handle. Therefore, the State Forestry Division assumed responsibility for the Ainaloa fire. Thirty-five forestry workers were flown to the Island of Hawaii from other Hawaiian Islands. These fire fighters, together with a handful of men from the HFD and six bulldozers, prevented the Ainaloa fire from reaching the town of Pahoa a half mile away. At 1:18 a m., a short-lived but heavy drizzle began falling, aiding fire fighters immeasurably.

On Feb. 28 and Mar. 1, respectively, the Creenwell Ranch and Ainaloa fires were controlled. All HFD members were withdrawn from Ainaloa, and state forestry workers maintained an around-the-clock watch for the next 10 days.

The Ainaloa fire had been started maliciously by five youths, 10 to 15 years of age. All have been arrested.

Once the Creenwell Ranch fire was under control, it was turned over to ranch employees. The fire continued to burn for many days in the deep organic matter overlaying the ancient lava rock. (There is no soil as such in that area.) The ranchhands literally had to dig the fire out.

The lava flow was posing an imminent threat to Royal Cardens by 2:47 a m. on Mar. I CD Chief Kim requested HFD assistance for a mandatory evacuation of all residents. Three units were dispatched with Battalion Chief Akau.

At 5 a m. Akau reported that the lava was less than a half mile from the closest homes and that it was moving 500 to 600 feet per hour. The flow’s front was 600 feet wide and about 30 feet high.

Heavy smoke and brush fires were in the area. Assistance from the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park was requested to handle the fires. Officials felt that few houses would be directly affected by the lava because it had taken a path diverting it from all but a corner of the subdivision. However, the brush fire threat was great.

Chief Ranger Dan Sholly of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park was asked to take complete charge of the Royal Gardens fire/ lava situation by HFD Chief Nagao at 12:05 p.m. on Mar. 2. This unprecedented move was dictated by the three simultaneous fires confronting the HFD and the exhaustion of HFD members.

Sholly immediately decided to fight fire with fire, to backfire extensively in front of the advancing lava. As Kim said at this point, “Our greatest fear is not the lava. Instead, it is the runaway brush fires.”

Sholly’s crews spent almost 12 hours burning a square mile of dense brush. The tactic was successful. No homes were damaged by fire but two houses were overrun by lava.

All volcanic activity stopped, temporarily the scientists said, at 3 p.m. on Mar. 4. Sholly’s fire fighters continued to backfire through the next several days, correctly assuming that the eruption would resume. It had indeed resumed.

March 4 brought yet another major brush fire. At 4:19 p.m., barely an hour after the eruption stopped, Tanker 5 reported that the Hawaiian Shores/Hawaiian Paradise Park fire had jumped the break and was again raging out of control.

Engines 3 and 5, Tanker 5, Medic 5, Battalion Chief Akau and Deputy Chief Francis Smith were dispatched. The flames defied control efforts, however, and by noon on Mar. 5 a major fire was in progress. Evacuation of the entire subdivision, over 500 homes, was ordered.

Bulldozed firebreaks, some of them 50 feet wide, and carefully placed backfires prevented major damage to any homes, although two outbuildings were destroyed. Fire fighters managed to contain the blaze at Makuu Drive, the first of four parallel streets in the development. Roadblocks were lifted by county police at 4 p.m. on Saturday.

photos by the author

The more than 18-mile perimeter of the Hawaiian Shores/Hawaiian Paradise Park fire, coupled with the few fire fighters available to maintain the watch, had permitted flames to cross the 40-foot-wide break and fan flames from a fire that had been placed under control more than two weeks previously. It is speculated that the fire burned underground through decaying organic materials to cross the break at that point.

This new outbreak at Hawaiian Paradise Park necessitated around-the-clock watches until Mar. 15 when substantial rains began.

One more challenge remained for the HFD. That came in the form of yet another brush fire on Mar. 13 at Hawaiian Acres, about 5 miles from the previous week’s fires. Once again, the same exhausted companies were first due.

Within six hours, more than 2500 acres were ablaze. This time fire fighters were unable to save some of the endangered houses. Eight were lost to the fire that eventually burned over 5000 acres. Once more, lack of water forced fire fighters to take a defensive stand, cutting breaks and backfiring. Never was it possible to attack the fire directly.

This fire also is thought to have been intentionally started, although at present no arrests had been made.

During the entire 10-week operation, only two persons were injured. One fire fighter received moderate injuries in a chain saw accident at Hawaiian Acres, and a scientist fell through a thin shell of cooled lava and into an incandescent cave underneath. Fortunately there was no molten rock present at the time. The scientist received second degree burns to his hands and legs.

Communication was the greatest problem in these emergencies. At the Hawaiian Shores/Hawaiian Paradise Park fire, for example, 18 agencies had personnel and equipment at the scene. However, there was no radio frequency common to all apparatus, causing predictable confusion about assignments for mutual-aid companies. This was solved by having one HFD officer meet arriving units and personally direct them.

Communications between fire and police were problematic at times also. For example, some residents were not notified by police of an impending evacuation because similar-sounding Hawaiian street names were misunderstood.

The HFD and CD have long advocated extensive planning, especially for rural subdivisions that lack water systems. Therefore, information was readily available about the nearest water sources, capabilities of HFD and mutual-aid apparatus, what private contractors could supply bulldozers, etc. Although these plans were not adequate for the simultaneous occurrence of four major incidents in the same district, it would be unreasonably critical to expect anyone to have foreseen such a situation.

Coordination and cooperation among the numerous agencies at the scenes was generally good. No serious problems occurred and, in fact, there were several delegations of authority and responsibility that could not have been anticipated. For example, the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park rangers assumed command at the eruption and the State Forestry Division took the Ainaloa fire. Both incidents normally would be the responsibility of the HFD and CD.

The most serious breakdown in communication and coordination occurred between police, CD officials and residents of the affected areas. Residents were not apprised of the reason why they could not return to their homes when they appeared to be in no danger. This lack of understanding resulted in several incidents of defiance by citizens which ended with their arrests. Meetings were held with community organizations to explain the necessity for the actions taken. This should eliminate future problems.

If one single lesson could be pinpointed, it would have to be this: Never underestimate the disaster potential in your response area. Always keep in mind the possibility of simultaneous major incidents.