Triangle Shirtwaist Toll Of 145 Is Still Largest For U.S. Industrial Fires

features

Pages from the Past

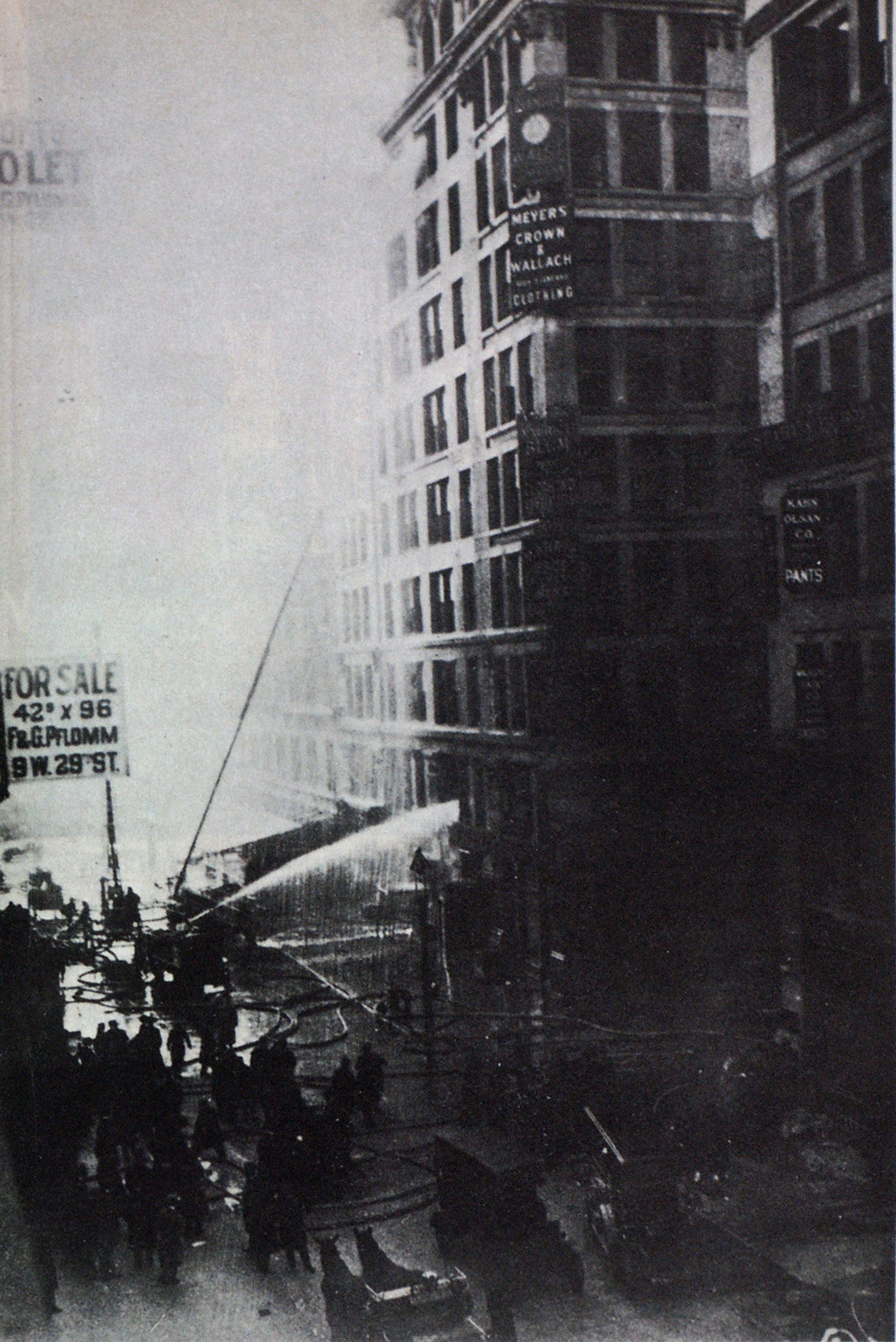

— Culver Pictures.

“A young man helped a girl to the windowsill on the ninth floor. Then he held her out deliberately, away from the building, and let her drop,” ran the story that William Gunn Shepherd, a reporter, dictated to the United Press office in New York from a phone near the scene of what has become known as the Triangle Shirtwaist fire.

“He held out a second girl the same way and let her drop,” Shepherd continued. “He held out a third girl who did not resist. I noticed that. They were all as unresisting as if he were helping them into a street car instead of into eternity. He saw that a terrible death awaited them in the flames and his was only a terrible chivalry.

“He brought another girl to the window. I saw her put her arms around him and kiss him. Then he held her into space—and dropped her. Quick as a flash, he was on the windowsill himself. His coat fluttered upwards—the air filled his trouser legs as he came down. I could see he wore tan shoes.”

Knockdown in 18 minutes

It took New York City fire fighters only 18 minutes to knock down the flames that had quickly spread through the top three floors of the 10-story, fire-resistant, loft building at Washington Place and Green Street on Saturday, March 25, 1911. In less than that time 145 employees, mostly young girls, were dead.

The ingredients for the greatest loss of life in an industrial fire in the history of the United States were highly flammable lawn, a sheer cotton fabric for the stylish shirtwaists of the Gibson girl era, combined with crowded workrooms, locked exit doors, wood sash doors with wired glass panels to the two enclosed stairways, 33-inch-wide stairs that had winders between floors, and an iron fire escape with 17 ½-inch-wide steps and 18-inch-wide platforms.

Ironically, the girls—the average age of Triangle workers was 19 were working overtime and were looking forward to dates that Saturday night with their boy friends. Many of them had a date with death.

Start of tragedy

The fire started about 4:42 p.m. on the eighth floor in the vicinity of the northeast corner of the building, almost simultaneously with the signal to stop work for the day,” said a report by the bureau of surveys of the New York Board of Fire Underwriters. “It is generally believed to have originated from a match or cigarette igniting scrap material on the floor in the vicinity of the cutting tables. Futile efforts were made to extinguish the fire with pails of water. It spread rapidly, however, due to the large quantity of inflammable material, consisting chiefly of thin cotton, lace and other trimmings for fancy shirtwaists in the process of manufacture.

—United Press International photo.

“In a very short time,” the report continued, “the fire had spread over the entire floor and communicated, principally out and in the windows, to the floors above. In addition to the windows, the fire may have communicated from floor to floor by way of the stair and elevator shafts, as the doors were undoubtedly open in part at least. All information indicated that there was a large accumulation of inflammable stock in process of manufacture, and this undoubtedly accounts for the exceptionally quick spread of the fire over the eighth, ninth and tenth floors.”

Before fleeing the eighth floor, Dina Lifschitz, the Triangle switchboard operator, phoned the ninth floor and got no answer. She got an answer when she rang the 10th floor and she sent a woman to find the bookkeeper, who was reported to be the only one authorized to call the fire department.

Passerby pulls street box

It was about this time that John H. Mooney was walking along the street when two bodies hit the sidewalk. Horror-stricken, he ran to the corner and pulled box 289 at 4:45 that Saturday afternoon. Within three minutes, Battalion Chief Edward J. Worth was on the scene and he called for three more alarms.

“According to the information obtainable,” the underwriters’ report stated, “the operators, crowded among the machines, chairs and goods on the eighth and ninth floors, were badly panic-stricken immediately after the start of the fire, and as a consequence made slow progress toward the exits.

“Considerable delay is said to have been experienced in opening the doors leading to the stairs at the southwest corner of the building as they opened inwardly and the women became jammed against them,” the report continued. “Practically all the employees on the eighth floor eventually escaped by way of the stairways and the elevators.”

A group of those on the eighth floor made their way to the fire escape and a few of them climbed through a broken sixth-floor window. However, they piled against the locked door to the Washington Place stairway. Their screams were heard by a policeman aiding other fleeing workers down the stairs at the sixth-floor landing. He managed to unbolt the door, but then he had great difficulty opening it because the women were jammed against it and the door opened toward those on the inside. Once the policeman got the door open, those inside made their way down the stairs.

Floor arrangements

On the eighth floor, where both cutting and sewing were done, 4-foot-wide work tables ran in five unbroken rows from the Washington Place (south) side of the building to within 18 feet of the north side of the building. This northern space was partially filled with stock, mostly on tables, and there was an aisle running east and west in this area. Thus, most sewing machine operators had to move between the rows of tables to the northern area before they could get to the two freight elevators in a single shaft at the northeast corner of the building or the two passenger elevators in a single shaft in the southwest corner. One stairway was alongside each elevator shaft.

The ninth floor had eight continuous rows of 4-foot-wide work tables with 240 sewing machines on them. These tables extended to within 10 feet of the north wall. This northern area also had a transverse aisle, as on the eighth floor, and there was stock in the area.

United Press International photo

The 10th floor contained the office, showroom, stockrooms and shipping department. Each floor had 9000 square feet of area.

Even in the underwriters’ report, there is confusion about the number of employees on each floor. In two different parts of the report, the number of persons on the eighth floor was given as 230 and “approximately 275” while the figures for the ninth floor were “230 hands” and “approximately 300 operators.” As for the 10th floor, the figures were 50 and “approximately 60 employees.”

Death trap on ninth floor

“Practically the entire loss of life was confined to those employed on the ninth floor,” according to the underwriters’ report. “More than half the number said to have been on this floor escaped. It seems apparent, however, that by the time this number had gotten out, the elevators had stopped running and the flames around the two inside stairways and outside fire escape, both on this floor and those adjoining, would not permit any further egress in these directions. The result was that all who remained on the floor until this condition prevailed were overcome by the smoke and fire or jumped out the windows … It is said that a few—probably 20—from the upper floors descended by way of the outside fire escape.”

Flames reaching out windows set fire to the clothes and hair of the girls descending the fire escape. The high heat caused the fire escape anchors to loosen from the wall and as the iron bent, some of those on the fire escape plunged to the one-story extension of the Asch Building. (The underwriters’ report said that “about 10 bodies are said to have been taken from the bottom of the court on the north.”) The windows alongside the fire escape at the Triangle Waist levels had iron shutters, and these shutters bent outward from the fire heat and one jammed the eighth-floor landing, which was only 18 inches wide. The fire escape steps were 17 ½ inches wide, according to the underwriters’ report and women were trapped on the eighth floor landing by a jammed, buckled shutter. “The flames leaped out from all the windows. Finally, the fire escape buckled and swung, flinging its flaming human load into the courtyard.”

Those on the 10th floor included Max Blanck, one of the Triangle Waist Company’s two owners, and two of his children. Blanck and some others decided that their best hope was to go up the single set of stairs from this floor to the roof. Flames rolled toward them and when they got to the roof, many had singed hair and burned clothing. The underwriters said that others got to the ground by the elevators.

Lone fatality on 10th floor

Clotilda Terdanova, who was on the 10th floor, was planning to quit work in a week to get married. She panicked and dove out a window. She was the only person on the 10th floor to lose her life.

The two elevator operators on duty ran their cars as long as possible between the fire floors and the lobby. Desperate workers fought their way into the cars and jammed them to double their rated capacity of 15 and there were reports of some persons sliding the cables. One girl on the ninth floor was said to have seen the elevator pause at the seventh floor. She jumped on the roof of the car, and then it started back up toward flames reaching into the shaft. Her screaming and pounding on the roof alerted the operator, who took the elevator to the lobby, saving her life.

“Approximately 25 bodies were found closely jammed in the (ninth floor) cloak room next to the stair shaft at the west end of the building,” according to the underwriters. “About 50 were found near the northeast corner back of a partition and clothes locker located 30 inches from the north end of the two tables nearest the east wall. Twenty were found near the machines where they worked, apparently having been overcome before they could extricate themselves from the crowded aisles. Most of them were near the east side. About 10 bodies are said to have been taken from the bottom of the court on the north. The balance of those killed—approximately 40—jumped from the windows to the street.”

Standpipe lines used

The fire was extinguished with hose lines off the two standpipe risers in the stairwells. Although some master streams were used, the fire floors were too high for the streams to penetrate them with any effect.

“The upper three floors were completely burned over and practically all trim and finish destroyed,” the underwriters’ report stated. “The damage to the structural part of the building on these floors was relatively small. The lower face of about one-fifth of the tile roof arches was broken off and the covering on one column supporting the roof was slightly broken. The parapet wall at the north court is out of plumb from 4 to 5 inches at top owing to the sagging, under heat, of the unprotected channel iron window lintels which support it.” The masonry wall building had a steel frame with cast iron columns and terra cotta block floor arches.

In addition to destruction of the contents of the upper three floors, there was some fire damage to contents on the first floor, where fire was spread by falling brands.

The Underwriters’ report pointed out that this fire illustrated “the prevalent neglect of ordinary precautions to avoid the outbreak of fires due to readily preventable causes.”

Building conditions defended

Fire and Water Engineering reported in its March 29, 1911 issue:

“Albert Ludwig, chief inspector of the (New York City) Bureau of Buildings… made the following statement: ‘The building could be worse and come within the requirements of the law. It is not required by law that elevators and stairways be enclosed. These are in this building, although the fire doors are not self-closing and on the upper floors of the stairway are made of oak and wireglass, instead of being fireproof.”

In the same article, Fire and Water Engineering stated, “Leonora O’Reilly, a leader in the strike in the company’s plant (Triangle Waist Company) last year, declared that to her certain knowledge the doors on the eighth and ninth floors of the building were locked fast at the time of the fire.”

New York City Fire Commissioner Waldo was quoted in the article as saying, “From indications, gates and doors appear to have been locked at the time of the fire. The fire commissioner is endeavoring to secure legislation which will create a bureau of fire prevention with sufficient legal power to install automatic and auxiliary fire appliances, to enforce fire preventive measures and to give to the department the right to insist on acfequate means of escape in case of fire. The fire department is the most competent to pass on the necessity for fire escapes, due to their experience with fires.”

The commissioner also commented, “There were two enclosed fireproof stairs with window doors and jambs. These doors were consumed by the fire and left the stairs open to the flames. These stairs were only sufficiently wide for one person to descend at a time and with winding steps at the turns. Entrances to stairs were blocked by partitions.”

Two partners acquitted

Blanck and Isaac Harris, the other partner of Triangle, were tried and acquitted on first and second degree manslaughter charges. The state was unable to convince the jury that the girls did not know that the ninth-floor door was locked.

Wide World Photo

In the crowd watching this tragic fire was the 29-year-old secretary of the New York Consumers League, Frances Perkins, who said that she and some friends she had been visiting nearby “got there just as they started to jump. I shall never forget the frozen horror which came over us as we stood with our hands on our throats watching that horrible sight, knowing that there was no help.” It was just 22 years later, also in March, that Miss Perkins became the first woman cabinet member as secretary of labor, a post she held for 12 years in the cabinet of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Marching eight abreast, mourners estimated that 100,000 participated in a funeral procession up Fifth Avenue Wednesday afternoon, April 5. The banner of Waistmakers Union Local 25 read: “We Demand Fire Protection.”

Commission appointed

The demands for fire safety legislation to protect workers in factories brought the appointment of a state factory investigation commission on June 30, 1911. Miss Perkins was appointed to this commission along with State Senator Robert F. Wagner, Assemblyman Alfred E. Smith, Samuel Gompers and H. F. J. Porter, who was the commission’s fire prevention expert. It was a commission of unusual talent. Wagner went on to become a United States senator, Smith became governor of New York and a candidate for president, and Gompers was president of the American Federation of Labor.

As a result of four years of work by the commission, New York State enacted 36 labor laws that provided model factory fire protection legislation.

As Miss Perkins was once quoted as saying, the 145 Triangle workers “did not die in vain and we will never forget them.”

Lessons learned

Recommendations made in the New York Board of Fire Underwriters were as follows:

- A fire drill and private fire department should be organized among the employees of all factories to prevent panic and extinguish fires. The plan of organization outlined in the recommendations of the National Fire Protection Association should be used as a guide for this purpose.

- All stairways, or a sufficient number of them, should be located in fireproof shafts having no communication with the building except indirectly by way of an open air balcony or vestibule at each floor. Hose connections attached to standpipes should be located on each floor in the stair towers for public or private fire department use.

- Stairs, if any, inside the building and elevators should be enclosed in shafts of masonry and have fire doors at all communications to floors.

- The provisions ordinarily necessary for fire escape towers might be somewhat modified in buildings equipped with a system of automatic sprinklers installed according to the standards of the National Fire Protection Association.

- Present buildings with inadequate fire escapes should be provided with automatic sprinklers and/or smokeproof stair towers, but additional outside fire escapes passing in front of or near windows should be discouraged.

- No factory building containing inflammable goods in process of manufacture, or employing in excess of a limited number of operatives (limit to be definitely fixed) should be without automatic sprinklers. No building over 60 feet high and containing inflammable goods, where a considerable number of people are employed, should be without automatic sprinklers.

- Automatic sprinklers should be installed in high buildings to control a fire and thus prevent it from spreading rapidly from floor to floor by way of outside windows. The use of wired glass in metal frames for all exterior windows would also retard such vertical spread of fire, but not so effectively as a complete installation of automatic sprinklers throughout the building.