BY J. SCOTT THOMPSON

In search of fire service excellence, I have concluded that nothing contributes to our success and survival more than training. However, training by itself is only half of the equation; there is a direct correlation between training and experience and the success and survival of firefighters. Training and experience must go hand in hand; the benefits of each cannot be fully realized independently. When we fight a fire from which nothing is learned, that fire is merely an event. Training that does not connect to reality is useless.

It is a common belief in the fire service that time in rank equals experience. This is not totally true. Too often, the assumption is that because someone has been going to fires for 20 years, that person has 20 years of experience fighting fires. A similar assumption is made about training: Because a person has completed the training, he has acquired the knowledge necessary for success. Nothing could be further from the truth. Experience is the sum of knowledge, practice, understanding, and proficiency. Training should have the specific goals of improving capabilities, confidence, and performance. In terms of training firefighters, the training must also be reality based and personal. These are very basic criteria for training and experience; anything less should be unacceptable.

There are many great programs and books on the subject of training firefighters and adult learning theories; however, there are a few nontraditional topics that are essential for the successful training of firefighters and fire officers but that are often overlooked. These topics focus on defining success, assessing needs, establishing standards, mastering the basics, and making training personal.

DEFINING SUCCESS

Although the American fire service shares basically the same mission, to save lives and property, there is a lack of commonly accepted principles or practices regarding how we should train firefighters and fire officers to carry out the mission. “The fire went out and everyone went home” is an admirable goal for any operation, but it is difficult to translate into the actual principles and practices that lead to success and survival.

To achieve success, it is important to understand what success is. When talking about training or mentoring, it is also important to be able to communicate what that success looks like. Thinking about all of the discussions I have had about training concerns and frustrations, it is obvious that too often the training failed before it was delivered. Why? Because those responsible for preparing the training neglected to take the time to examine and define the desired outcome and how the training should impact the individual, the team, and the organization as a whole. They neglected to define success.

In many of the departments I have evaluated, training was fragmented and lacked direction, consistency, and continuity among shifts and stations. The primary reason for this is that there were no clearly defined outcomes; what it takes to succeed was not defined.

In The Colony (TX) Fire Department (TCFD), what it takes to succeed is clearly defined. The department’s Excellence Vision and Professional Standards (referred to as the “Kool Aid”) describe the philosophy and the chosen culture. These standards are the foundation for service delivery, hiring, promotion, mentoring, training, and professional development efforts. It is important to realize that it’s not solely the content that is important but also the insight that comes from the process of developing the standard that benefits the organization as a whole. The Excellence Vision and Professional Standards define The Colony Way. The orientation of new employees and newly promoted officers, in-service training, and the mentoring process each reinforce what the leadership of the organization views as success.

ESTABLISHING STANDARDS

Once success has been defined, the standards for achieving success must be developed. Some may disagree, but I believe it’s the chief’s responsibility to set the standards for the organization. The reality at the end of the day is that what the organization does and doesn’t do falls in the chief’s lap. The leaders of the department should be held accountable for the effectiveness and efficiency of the department. My question always is, if the chief isn’t setting the standard, who is?

There are many benefits associated with establishing well-defined standards. Not only do standards provide a method for determining operational wins and losses, but they also are tremendous training and leadership tools for battalion commanders, company officers, training officers, and mentors. In the absence of standards, the organization can expect inconsistency, disagreement, and substandard performance. Standards that come from the top greatly minimize the potential for operational inconsistencies and go a long way in promoting one mission, one department, and one way.

The Colony’s SMART Standard

Our department’s SMART3 (Strategic, Managed, Aggressive, Risk Regulated, Tactics, Tasks, and Techniques) is an operational standard that defines and communicates The Colony Way of operating at structure fires. The standard was developed to redefine operational principles and practices while introducing operational changes based on Underwriters Laboratories (UL) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) fire dynamics research. SMART provides a sensible and logical approach that can be used for preparation (training), response (operation guidelines), and evaluation (benchmarks) while emphasizing the importance of coordinated operations. The review, evaluation, scrutiny, and discussions that occurred during the implementation of the standard produced several unanticipated benefits. The biggest benefits were an increased level of ownership of fire operations and a better understanding of the importance of every task to the overall outcome of the event.

In summary, the SMART standard incorporates the following:

- There will be a strategy to address each incident problem identified during size-up.

- All operations will be managed using standard response objectives, coordinated standardized assignments, and TCFD incident management and accountability systems.

- To accomplish the mission requires aggressive, risky (by definition) actions. As an organization, we acknowledge that asking our people to safely conduct vent-enter-search or rapid intervention tasks was somewhat of an oxymoron. Although we realize certain precautions can be taken to increase our chances of success and survival, these operations are not safe.

- The level of operational aggression will be risk regulated. Based on these realizations, the emphasis has shifted from being safe to being smart. Training on sensible aggression vs. reckless aggression is ongoing.

- Training is focused on the tactics, tasks, and techniques necessary to solve the incident problems based on operational capabilities and limitations. The three together emphasize how individual technique impacts tactics and the importance of coordinating tactics and tasks. This is referred to as 360° training; everyone has a job, and every job has an impact on the outcome of the operations.

Combining the SMART standard with training on identifying operational capabilities and limitations has provided an effective and unique method for training decision makers on acceptable vs. unacceptable risks.

ASSESSING NEEDS

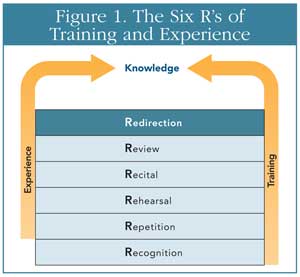

Once success has been defined and standards established, the next step is to assess the training needs necessary to meet the standards that lead to success and survival. This is necessary to ensure the basics are addressed and skills and knowledge are sufficiently developed. The Six R’s of Training and Experience (Figure 1) is one method that can be used to assess the knowledge obtained from training and experience.

The Six R’s of Training and Experience

MASTERING THE BASICS

“If you master the basics, the rest will fall in place.” “The basics will save you.” You may have heard these statements, both of which are true. Training for success and survival must start with the basics, which should remain a training priority until the established standards are met.

Does this sound familiar? Firefighter Smith checks out his self-contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) at the beginning of each tour. Like many firefighters, he leaves his SCBA in the seat-mounted bracket and checks the breathing apparatus from the exact opposite perspective as when the SCBA is on his back. He goes through the check and waits 30 seconds until the integrated personal alert safety system (PASS) sounds. He then hits the reset button twice and shuts down the air. If Firefighter Smith does this check every tour but only operates the SCBA while it is on his back and only manually activates the PASS on rare occasions, what are the chances that he will perform these actions in a manner that will save his life in an emergency? This is pretty basic. The fire service has preached the importance of the basics for years. What exactly are the basics, and what are the benchmarks that lead to an acceptable level of competency?

Ensuring that there is a firm grasp of the basics is essential. There are many opinions on what constitutes the basics. I view the basics as the knowledge that is essential for success and the tasks and techniques that must be performed with flawless execution for self-survival and the survival of others. In reality, this is the basic of the basics; however, it provides a starting point in terms of training on the basics and making training personal. To broaden this definition, there are obviously basics for conducting search operations, venting, initial fire attack, and so on. What’s viewed as basic tasks and techniques will vary based on staffing, operational philosophy, experience, resources, and other factors. Part of defining success is to define the basics that must be mastered—performed correctly 100 percent of the time.

Time and time again, I hear from trainers who are frustrated because the troops don’t get it. If the training needs have been assessed, realistic learning objectives have been developed, the training content is accurate, and sufficient time was committed to preparation, the training should produce the desired results. If not, there is a better than good chance that overtraining has occurred.

Overtraining is at epidemic levels in the fire service. Overtraining is not training too much; it’s training above the experience and skills level of the student. Overtraining occurs when advanced principles or practices are introduced to individuals who do not have knowledge of the necessary basic skills. The existence of this knowledge should be verified before introducing advanced concepts.

Overtraining can occur also when a department does not understand or realize its operational capabilities and limitations. For example, in many cases a suburban or rural department is unable to attack a fire with the same level of aggression as an urban department because of the lack of experience and resources. Because they perceive aggression as success, these departments train on the same tactics used by departments that have fewer limitations and much greater capabilities. The reality is that operational capabilities and limitations vary greatly from department to department. Departments must honestly assess what they can and can’t do and develop training that stays within those parameters. History has proven that when operations extend beyond the capabilities of the resources on scene, bad things happen.

It has been my experience that too many firefighters and fire officers don’t know what they don’t know. This is not a criticism but a fact. The fire service has tried so hard and for so long to simplify an incredibly complex subject that many of the essentials have been overlooked. An example of this is associated with the scientific information available to the fire service. The UL and NIST research projects scientifically illustrate just how much we don’t understand about our trade. Applying science to firefighter tactics, tasks, and techniques has been providing us with some very basic insight into principles and practices that have been in place for years. What else don’t we know?

BASIC DRILLS The Basic Big 5

For the past 13 years, I, as division chief of training and the chief of department, have been using the Basic Big 5 as the foundation of our department’s regimen for fire training. In fact, I often recommend that this be the first priority when developing or revising a training program. Although the topics may vary, the Basic Big 5 cover the five areas most critical for operational success: hose drills, ladder drills, personal protective equipment drills, firefighters assist and survival principles and practices, and the use of hand tools. Hands-on drills on each are conducted at least quarterly, and each of the Basic Big 5 is evaluated during multicompany or battalion drills.

First 5 Minutes

Another basic drill for success is the First 5 Minutes drill. Over the years, I have heard Chief (Ret.) Alan Brunacini of the Phoenix (AZ) Fire Department emphasize how the “first five minutes will determine the next five hours.” Based on the importance of the first minutes of an incident, the First 5 Minutes drill focuses on size-up, apparatus placement, water supply, initial line selection, deploying initial resources to address the tactical priorities, and resource needs. Each is a basic, and all are critical for a successful outcome. Additionally, building construction, fire behavior, strategy and tactics, situational awareness, and risk management are discussed.

MAKING TRAINING PERSONAL

There are few things more personal than survival and success. Training and experience impact both. My experiences with training and leading firefighters and fire officers and extensive research on training firefighters have convinced me that training that impacts on an emotional/personal level produces the best results. In his book Deep Survival, Lawrence Gonzales writes, “What you really need to know for survival purposes is that a system called emotions works powerfully and quickly to motivate behavior”(page 30). If in fact this is true, which I believe it is, we must spend at least as much time addressing the mental aspects of survival as we do the physical aspects.

A great tool for personalizing training is the LODD report. I was introduced to the concept of this training by a former chief, and in the 12 years in which this type of training has been conducted in the organizations with which I have been associated, firefighters’ lives have been saved. One incident involved a captain involved in a near-miss situation at a structure fire; he specifically recalled from his training a portion of an LODD report that gave him the motivation to not give up and that ultimately resulted in his survival.

It goes without saying that the extremely dangerous environments in which firefighters work have a significant physical and psychological impact on the body and mind. Survival stress reaction (SSR) is a term used to basically describe how the body responds to a perceived life threat. Most of the extensive research that has been conducted on SSR has been done with the military and with law enforcement personnel. This research can and should be applied to the fire service to a greater degree than it is. There is an application for SSR in the training of firefighters on self-survival skills and also in analyzing LODDs and near misses. By better understanding how the body reacts in life-or-death situations, we can better prepare firefighters with hands-on training, responsibility and consequence awareness, dynamic simulation training, and confidence-building exercises. Without at least considering the impact of SSR in self-survival training, we may be setting our people up for failure by training them to rely on skills and cognitive training that they may be physically and mentally unable to perform.

The research on SSR gets very interesting when you acknowledge the possible impact SSR has on cognition involving common fire training methodology. Cognition basically involves knowledge, comprehension, and application. SSR may alter each of these components of decision making. The ability to recall or recognize specific information or procedural patterns critical for survival may be diminished. The impact of SSR when evaluating training and experience using the Six R’s cannot be ignored. Think about how firefighters are trained to respond in a Mayday situation, and then consider how SSR may impact firefighters’ ability to react. Firefighters are commonly taught to recognize certain situations and take the necessary action for survival. They are instructed to talk on the radio and give a standardized report and then to recall and perform self-survival procedures, many of which involve fine/complex motor skills. The question is, are we training our firefighters to do something that their body and brain may not allow them to do? This is very personal.

To prepare firefighters to compensate for SSR, training must build skills confidence and promote visualizing survival, teaching techniques to control breathing, and skills that rely more on gross motor skills and less on fine/complex motor skills. We must prepare firefighters for where their body is going and the actions to take to delay or lessen the negative impact associated with SSR.

Another reason for making training personal is that training received on an emotional level results in training with extended brain life. Call it mental markers, mental imagery, spinal tuning, or whatever. As much as the fire service preaches that decisions should not be made on the basis of emotion, it is impossible to remove emotion from the decision-making process in situations with minimal information and limited discretionary time. So as trainers, we would be wise to consider how emotions will impact training in real-life situations. In his book On Combat, Lt. Col. Dave Grossman addresses the destructive nature of “killing” firefighters fictitiously in training. He says “This type of training only teaches you to die.” Are we teaching firefighters to survive or to die?

I suppose there are many ways to achieve fire service success. West Coast, East Coast, old school and new school, direct, aggressive, indirect, and transitional are just a few of the many buzzwords used to describe a preferred method for fulfilling the mission. Although it seems as if everyone has a position on many subjects in the fire service, we seem to be less committed to taking a position on the best way to train and prepare our firefighters and fire officers for success and survival. Unfortunately, firefighters continue to die and be seriously injured in the same manner as they did for the past 200-plus years. Egos, ignorance, and plain stupidity continue to defy common sense, science, and the realities associated with modern firefighting. To be successful and, more importantly, to survive, we must continually evaluate the changes to the modern fire environment and then be willing to change our principles and practices to meet the demands of reality. It is through the commitment to understand, progressive training, and the development of experiences that we will realize the best chances for success and survival.

Survival Stress Reaction

When the body perceives a significant threat, the heart rate [beats per minute (bpm)] begins to increase and the ability to perceive and react is impacted. As the heart rate continues to increase, fine/complex motor skills (hand-eye coordination, multitasking, finger dexterity) may be compromised. Gross motor skills (skills that involve the larger muscle groups) improve. Studies on survival stress reaction suggest that as bpm increase, the following may occur:

- 115 bpm: Fine, complex motor skills may be lost, impacting the ability to operate a radio, activate alerting devices, or execute emergency procedures on breathing apparatus.

- 145 bpm: Hearing may be impacted.

- 175 bpm: Vision narrows, resulting in tunnel vision. It may also become difficult to focus on close objects such as air gauges and radio channels.

- 185-220 bpm: What are commonly referred to as “brain farts” or deer-in-the-headlights reactions often occur.

Reference: Stockholm Krav Center http:/www.krav-maga.nu/ssr.htm.

J. Scott Thompson will present “Training Basics and Essentials for the Fire Service” on Wednesday, April 9, 1:30 p.m.-3:15 p.m., at FDIC 2014 in Indianapolis.

J. SCOTT THOMPSON began his fire service career in 1981 and has served as a career and a volunteer firefighter. He is the chief of The Colony (TX) Fire Department. He has been a presenter and a H.O.T. instructor at FDIC since 2002. He has a bachelor’s degree in emergency administration and planning.

Fire Engineering Archives