This report was adapted and excerpted primarily from South Canyon Fire Investigation, a report of the Storm King Mountain incident investigation conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service; and the U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management and published August 17, 1994. Supplemental information was obtained through telephone interviews with involved parties. Interagency follow-up actions, recommendations, and conclusions were adapted and excerpted from Report of the Interagency Management Review Team, South Canyon Fire, submitted by a team of reviewers from the Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Forest Service, and National Weather Service.

Fire Engineering provides this information so that firefighters and future firefighters will learn the lessons that will help prevent such a tragic event from happening again. We salute firefighters Kathi Beck, Tami Bickett, Scott Blecha, Levi Brinkley, Robert Browning, Doug Dunbar, Terri Hagen, Bonnie Holtby, Rob Johnson, Jon Kelso, Don Mackey, Roger Roth, James Thrash, and Richard Tyler, who made the ultimate sacrifice in the line of duty.

An early report identified it as a small fire with Olow spread potential.O Numerous other fires in western Colorado demanded a higher firefighting priority. But on the afternoon of July 6, 1994, the fire on Storm King Mountain in less than an hour developed into a fast-spreading, dangerous fire culminating in a blowup that took the lives of 14 firefighters.

HIGH FIRE ACTIVITY

Storm King Mountain sits in the White River National Forest, on land administered by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Grand Junction District. It is two miles north of Interstate 70?a major east-west highway?and seven miles west of the city of Glenwood Springs, population 7,000.

The summer of 1994 was one of continued drought for western Colorado. Precipitation levels in Glenwood Springs for the eight months preceding the Storm King Mountain Fire were 42 percent below normal, and temperatures were higher than normal. The National Weather Service reported that June 1994 was the hottest month on record in Colorado. Fire danger indices for the Grand Junction District were the highest recorded in 21 years. As of early July, fire incidents in the district were twice the annual average; fire teams had responded to five times the number of fires in an average year.

In the first two days of July, dry lightning had started 40 new fires in the Grand Junction District. The district?and large sections of the western United States?was experiencing a season of heavy wildland fire activity and stretched firefighting resources.

THE OSOUTH CANYONO FIRE?EARLY STAGES

On Saturday, July 2, 1994, lightning sparked a fire about seven miles west of Glenwood Springs and 11U2 miles from the community of Canyon Creek Estates. At 1100 hours on July 3, the Garfield County Sheriff reported the fire?calling it the OSouth Canyon FireO (though its more accurate location was Storm King Mountain)?to BLM?s Grand Junction District Dispatch. He believed the fire to be on private land. The Garfield County Volunteer Fire Department reported that the fire had a high spread potential and requested aerial support. Grand Junction District Dispatch indicated that all resources were occupied but that an air attack would be forwarded should action be needed. At this time the BLM district was responding to numerous other fires with a higher priority.

Three hours later, the county sheriff?s office reported to District Dispatch that the fire covered one-half acre and was very active and that the sheriff approved the use of aircraft (required in cases of BLM assistance on private lands). District Dispatch requested from BLM Western Slope Fire Coordination Center (with the responsibility of distributing resources in western Colorado) a load of smokejumpers, an air tanker, and a lead plane to South Canyon and to other fires reported in the area.

A BLM engine crew arrived at the scene and met with the Garfield County sheriff. The engine foreman completed an initial size-up and reported several conclusions: The fire was on BLM-administered property; in his estimation, it had a low spread potential; and it should be OobservedO because of steep terrain, inaccessibility, low spread rate, and higher-priority fires in the district. The Grand Junction District fire control officer later in the day agreed with this assessment. The officer requested that resources be assigned to the Storm King Mountain fire the next day.

The three aircraft requested for the fire were diverted to other fires. Meanwhile, the District fire control officer requested of Western Slope that resources be reassigned to the South Canyon fire.

On July 4, 36 fires were burning in the district. Five were new, two of which exceeded 100 acres. At 1450 hours, a resident in the area reported that fire activity on Storm King Mountain was increasing. The U.S. Forest Service, Sopris Ranger District, radioed that an engine crew was en route. BLM already had released members working other fires and directed them to South Canyon. At 1630, BLM Firefighter Butch Blanco and crew and a Forest Service crew met at Storm King Mountain. Blanco requested an air tanker but was told there were 18 requests ahead of his. Later he called for a helicopter; none were available. Blanco decided to delay the attack on the fire until the morning because of terrain, forthcoming darkness, safety concerns, and equipment needs. The crews left the area. At 2109 hours, an aerial observer reported, OThe fire is in steep and inaccessible terrain. It is burning to the northeast on the ridge. The area is too steep for crews and has few if any escape routes. The fire is actively burning in all directions. Helicopters with buckets could be very effective.O By 2302 hours, the Forest Service crew was moved to another fire.

On the morning of July 5?a morning that brought a weather forecast of very high to extreme wildfire danger, with a Ored flag warningO (see sidebar on page 59)?seven BLM firefighters hiked from the east drainage (canyon) to the north-south ridge of Storm King Mountain, about 1,000 feet in elevation above the fire in the west drainage. Blanco was the incident commander and Firefighter Michelle Ryerson the squad leader. The firefighters cut a helicopter landing area on the ridge (Helispot 1) and then began constructing a fireline down the west flank from the ridge. By 0800 hours, the fire had grown to 29 acres but was not intense?fingers of the fire burned slowly into the west drainage, predominantly in pinyon-juniper vegetation.

Blanco requested additional personnel?another engine (two firefighters), a helicopter, and two OType IIO crews totaling 20 personnel (a Type II crew indicates the second highest order of firefighting capability). District Dispatch substituted a crew of eight smokejumpers. Blanco also requested an air tanker drop. Two retardant drops were made: along the north and south fire flanks. Further drops were suspended on agreement by the IC and the pilot on the north side of the fire because of steep terrain and gusty winds and on the south because of the concern that the drops could cause a rockslide onto the interstate highway that skirted the southern edge of the mountain. Furthermore, as Blanco remarked in a postincident statement, ORetardant is not effective without the people to support it.O

At 1730 hours, Blanco and his seven-member crew left the scene to make equipment changes at the BLM district office: The two chain saws they brought to the fire were in need of repair. (They did not request additional equipment from the incoming smokejumper team.) They had cut a line about 400 feet down the slope. On the way out of the fire area, Blanco and the crew discussed the hazards of building a fireline downhill.

Fifteen minutes later, eight U.S. Forest Service Smokejumpers began arriving on Storm King Mountain. The smokejumper spotter stated that the fire was 20 to 30 acres in size and was Obacking down slowly into the drainagesO on both sides of the west canyon and to the southwest and that there were light winds. He noted that Oalthough the terrain was steep and the brush heavy in places, I thought it could be caught.O However, a smokejumper on the ground indicated to Dispatch that winds were erratic. Jumper-in-Charge Don Mackey contacted Blanco for orders and was instructed to continue the fireline down the west drainage, which the smokejumpers did.

Within two hours, the fire had increased significantly. The winds had increased from five to 12 mph and were gusting to more than 20 mph. At 1944 hours, Mackey called Blanco and reported that the fire jumped the west flank fireline and was Oburning actively.O He pulled the smokejumpers off the west flank and began constructing a fireline down the east drainage instead.

By 2000 hours, the fire had grown to 50 acres and burned into a large, dense section of Gambel oak, under which the ground was covered with a two- to three-inch mat of leaves and vegetative debris. Mackey requested additional firefighting resources?two Type I (highest level) crews. At 0030 hours on July 6, he discontinued line construction down and along the east drainage, as footing became difficult. The firefighters noted active fire on the ridgeline in the early morning?it had burned over the helispot and fireline?and became concerned that the fire might burn over their gear at the jump site. They decided to move their equipment come daybreak.

Although the South Canyon was in the area designated as a Fire Exclusion Zone?an area in which fires are to be fully suppressed (the management objective is to have 90 percent of the fires in the Fire Exclusion Zone controlled at 10 or fewer acres), only 15 personnel were committed to the fire at this time, and only eight were on the scene.

JULY 6, A.M.

The National Weather Service, as it had for several days before, issued a red flag warning for July 6. The forecast called for winds of 10 to 20 mph at 1100 hours, increasing to 15 to 30 mph by 1300 hours; by 1500 hours the winds were to shift to the northwest at 15 to 25 mph, with gusts up to 35 mph, as a cold front moved in. This forecast was noted by Grand Junction District Dispatch. In addition, the Dispatch report completed at 2240 hours on July 5 for the following day indicated next to its notation of a red flag warning that there was Ono relief in sight.O Furthermore, the report warned, radio communications would be Oinadequate for [the] fire load and safety is in jeopardy.O

There were still 36 fires burning in the Grand Junction District of western Colorado.

At 0430 hours, District Dispatch contacted Blanco, at this time off-site and preparing to hike in to the fire, and summarized the weather forecast for the day. This did not include mention of the red flag warning. However, Blanco recalled after the incident that ODispatch indicated that out-of-the-ordinary weather conditions were expected.O

At 0530 hours, Mackey requested aircraft for reconnaissance and gear removal, in addition to the request for resources he made the evening before. At 0630 hours, Dispatch assigned the Prineville Interagency Hotshot Crew to the fire and informed Mackey that the helicopter used to drop them off could be used for reconnaissance. Meanwhile, the eight original smokejumpers cut a fireline north along the ridge from Helispot 1.

At 0800 hours, the Prineville Hotshots left Grand Junction, Colorado, for the helicopter base from which they would depart to Storm King Mountain. Shortly after 0800 hours, Blanco arrived with his team and, at the suggestion of a helicopter pilot, instructed firefighters to construct a second helicopter landing area (Helispot 2) north of Helispot 1, on more level ground.

Blanco and Mackey discussed the operational plan for the day: improve the fireline along the ridge between the two helicopter landing sites and build a fireline down and across the west drainage. Several firefighters, including the IC, programmed their radios to receive NOAA weather forecasts for the day. These forecasts did not include warnings about potential fire behavior or red flag warnings.

At 0915 hours, Blanco was informed that a second crew of smokejumpers was headed to the fire. Fifteen minutes later, a helicopter arrived to take Blanco and Mackey on a reconnaissance flight. Initially, District Dispatch limited use of the craft to Storm King Mountain to four hours (it did, however, remain on scene for the day). Blanco and Mackey made a second recon over the site. They drew a map of the fire. It did not include the fingers in the lower west drainage. At least one firefighter believed that Mackey was unaware of the fingers of fire.

Fire flanked 1,000 feet from the night before. The fire in the litter under the Gambel oak patch that had ignited the evening before was moving laterally and down the slope at a rate of 70 feet per hour. It was, by midmorning, 125 acres in size.

While airborne, Mackey directed the smokejumpers to begin constructing a fireline downhill along the fire?s west flank. A firefighter stationed at the South Canyon helibase and assisting on the recon flights recalled of the discussions about strategy, OGoing indirect, they knew they would get a good burnout, but weren?t sure they could hold the fire. They decided to go direct with the knowledge that more resources were coming.O

Back on the ground, however, the strategy was questioned by several smokejumpers who expressed concern about the lack of safety areas in the canyon and escape routes out of it. Mackey and Smokejumper Kevin Erickson discussed the issue. The fire to that point, with the exception of limited fire activity on the ridge in the early morning, was moving out and down, and farther down the canyon the brush was sparse. OHe [Mackey] said it was sparse in the bottom and we could probably get away with it…. Not burning too active. I was going by his judgment, his best judgment was to go direct,O Erickson stated.

The firefighters began constructing a fireline six to seven feet wide with a 16- to 18-inch scrape, portions of which ran through the dense Gambel oak.

The second crew of smokejumpers, led by Jumper-in-Charge Dale Longanecker, arrived at 1037 hours and was instructed to reinforce the west flank fireline. Longanecker recalled in his official statement his first impressions of the scene. OI had looked at it from the air. I could see the bottom fingers in the drainage from the airplane. It looked sparse enough in the drainage that it looked like a safe area, especially when compared with the continuous fuels in the brush field. Don [Mackey] had gone up in the helicopter and looked at it, too. I met with Mackey to discuss the planned action. We talked it over. The line was in a hazardous area. We questioned whether we should be in here at all. We looked at the area. The winds were light at that time. There was not much fire activity. I figured that with 16 smokejumpers and a hotshot crew we could hook the fire before the front passed.O

Winds at this time were noted as between zero and five mph. There were now 25 ground personnel working on the Storm King Mountain Fire.

At approximately 1115 hours, fire ignited a small section of Gambel oak about 40 yards from the ridgetop fireline, from where it ran to the top and jumped the ridge fireline. This spot fire was extinguished with a helicopter water drop and the line maintained by ground crews.

Fire activity on the ridgeline in the morning, according to BLM Firefighter Jim Byers, was Oquiet.O He testified, however, that Oaround noon Mackey came up to me and said, OThe fire is starting to push the line up ahead.? O

JULY 6, P.M.

At 1230 hours, half of the Prineville Hotshots team assigned to the fire?Crew Superintendent Tom Shepard and nine firefighters?arrived on the mountain after a considerable delay because of confusion at the staging base. There was an additional delay in the arrival of the second half of the team?10 firefighters?because, as Byers recounted, the pilot Ohad to keep switching from shuttle missions to buckets to cargo and it took 1400 hours until the whole Prineville crew made it up to the fire.O The Prineville crew had not been briefed in Grand Junction on local conditions, fuels, or fire weather forecasts prior to their drops on the scene.

Blanco deployed the first group of hotshots on the west flank fireline. Shepard and Blanco remained on the ridge. Shepard testified, OBlanco was in a hurry to get them on the line with the smokejumpers. At the time the fire was innocent looking, but not dead.O Blanco and Shepard went to Helispot 1 to discuss strategy, which, according to Shepard?s statement, was to Otie off the west end, don?t worry about the east, take the line to I 70 and burn out. Avoid building underslung line.O

Neither Blanco nor Shepard descended the west flank to check the fireline and conditions. With Longanecker functioning as line scout, Mackey was supervising the entire line. Radio contact from command to personnel in the canyon was infrequent. Smokejumper Anthony Petrilli testified, OThroughout the fire, I didn?t see Blanco…. I didn?t hear him talking on the radio very much…. I did hear a lot of other radio traffic.O Furthermore, the ridge?given the slope, terrain, and brush?did not offer a good vantage point for monitoring the firefighting actions and fire activity below.

Between 1200 and 1300 hours, winds increased from 10 to 22 mph, with gusts to 30 mph. Weather briefings, from the start of the day onward, were insufficient, both from District Dispatch and on the fireground itself. It appears that most firefighters on Storm King Mountain had an understanding that the weather was going to change, with a cold front moving in, but did not appreciate the potential magnitude of that change. BLM Firefighter Brad Haugh indicated that no weather briefing was made but that NOAA weather forecasts were communicated Othrough people with radios to make sure they understood and heard [it]O?but again, the local weather forecasts are developed for the general listening audience and not for firefighters. Smokejumper Eric Hipke stated that he Oknew about [the] cold front, which infers wind changes. Had no warning of extreme winds.O Shepard testified that on his arrival he Otalked briefly about the weather and fuels,O but red flag warnings were not mentioned, nor was the reburn potential mentioned. He was told that line fuel moistures were low. Several Prineville Hotshots, in a group statement after the fire, demanded to know Owhere the communications line broke down with the red flag warning.O

Blanco testified, OI listened to the weather forecast NOAA with Mackey and Shepard. I remember that there would be winds or a frontal passage. It was a typical weather forecast. The jumpers punched the weather frequency into their radios. Dispatch indicated that out of the ordinary weather conditions were expected. No on- site weather was taken. There was no indication that a spot weather forecast was needed.O

Fireline construction was proceeding quickly. At approximately 1300 hours, a flare-up on the corner of the west flank fireline forced several firefighters up the drainage to the ridge. Testimony indicates that Mackey may have reconsidered the direct strategy at this point. Some firefighters also questioned the strategy at that time. But after a helicopter water drop on the flare-up was successful, the firefighters resumed their task. Petrilli testified, OMackey came back to us and said that we were pulling out. Longanecker called him back on the radio and said to wait and that bucket drops could help. The bucket drops cooled the area so we started back down again.O Longanecker stated, OFolks knew going downhill was Bad Deal?but with 16 jumpers & IHC [Hotshots] Crew they could do it.O

By 1400 hours, most of the firefighters on the west flank had made it to what they called the Olunch spot,O in an area that had been blackened by the fire the night before. At about 1425 hours, Mackey called the hotshots back to improve and hold the fireline. Soon after, Longanecker made his way farther down the canyon to scout out the area.

At 1430 hours, the second half of the Prineville Hotshots crew was dropped on the scene. They were instructed to hold the fireline along the ridge. There now were 54 personnel working the Storm King Mountain fire?16 smokejumpers, 20 hotshots, six helitack personnel (trained in the use of helicopters for fire suppression), and 12 firefighters from the BLM and Forest Service. Twenty-two worked the fireline on the west flank, supervised by Mackey. Twenty-two worked the fireline on the ridge. Two helitack members were at the second helicopter landing site (Helispot 2). Six personnel worked at the helibase (off-site base for helicopter operations). Blanco commanded from the ridge line.

Blanco radioed District Dispatch and indicated that Othings looked good.

At about 1510 hours, Longanecker radioed to the jumpers at the lunch spot to come down to his location, about 200 yards from the bottom of the drainage near a double draw at the southern end of the ridge. He was about 375 yards away from them. Six smokejumpers headed in his direction but hesitated. Petrilli testified, OI told him that I didn?t think it was a good idea making more line, since we are having trouble holding the line we already had….[W]e were already spread thin.

Firefighters on the ridge took a break about this time. Byers, in the group, later stated, OWhile we were sitting there the winds were calm…. Out of habit we started asking each other what we would do if things go bad, where is the escape route? Back toward H2 [Helispot 2] or if things hit the fan, down into the [east] drainage and follow our hike route that a.m. H1 not being considered as a safety zone because it was up a steep hill.

At 1515 hours, personnel at the helibase reported an increase in fire activity west of Helispot 1.

THE COLD FRONT MOVES IN

The cold front moved into the area as expected. At 1523, fire spotted across the 20-foot-wide fireline at the ridgetop. Firefighters contacted Blanco, confirming several spot fires across the line. Blanco requested helicopter water drops for these areas and radioed to District Dispatch that winds and fire activity were increasing. Blanco testified that during this time Mackey was continually requesting aerial assessments from the helicopter pilot making water drops.

Firefighters completed the ridgetop fireline from Helispot 1 to Helispot 2 at approximately 1530 hours. Shortly thereafter, Longanecker, down the canyon, radioed Petrilli for a sawyer and two diggers. Petrilli stated, OThomas, Shelton, who had the other radio in our group, and I started down. We walked 10 yards and then stopped. The fire made a run in the crowns up the hill from Longanecker. We were impressed with the 100 foot flame lengths and the radiant heat we were feeling even though the fire was 250-300 yards away. What was even more impressive was that the ground fuel was already burnt from earlier during the fire. The fire would travel 150 yards in 15 seconds…. I told Longanecker to look beside him where the runs were starting. He said that he saw them and that he was fine. We told Longanecker that we didn?t want to come down and I thought that he should get out of there.O

At approximately 1545 hours, Longanecker radioed for water drops on the fire near his location. At this point he did not feel imminently threatened: He had identified what he considered to be safe areas?the lunch spot and an area of double draw that he characterized as an open area with Oan occasional tree and a lot of bare ground.O He received one drop. Then fire activity on the ridge increased considerably. A reburn southwest of Helispot 1 had 100-foot flame lengths. BLM Squad Leader Michelle Ryerson requested water at the top. Byers recounted that Longanecker and Mackey were conversing over the tactical channel that Othings were heating up down there…. I told Michelle that the people down below might need bucket support…. Michelle checked with Mackey and he indicated that he did not need bucket support.O Blanco stated, OWhen the first bucket drop came in, somebody said, ONo go ahead and take it? on the radio from down below.O Blanco thought that person was either Mackey or Longanecker. The helicopter dropped water on the ridge fires, with little effect.

The winds now were very strong and gusting heavily?about 45 mph at the ridge.

At 1600 hours, the fire blew up. Starting from a low point on the east flank of the west drainage, it crossed rapidly to the other side, then violently, explosively back again?and now was making a run at the firefighters both at the west flank and at the ridge.

THE BLOWUP

Blanco testified, OMackey was asking the pilot, OWhat?s it look like up there? while 93R [helicopter] was returning…. As the second drop was approaching it just happened. I did not hear anything about a spot fire on my radio. Tom [Shepard] or Rich [Tyler] saw the fire was active and blowing up. I couldn?t see well from my location because of the trees on the ridgeline…. I used the radio work channel and started hollering for people to get out.O Blanco?s radio transmission was 1600 hours.

Petrilli was perhaps in the best position to observe the blowup. First he radioed Longanecker. Then at 1602 hours he radioed Mackey that the fire had crossed the canyon and was Orolling.O Later Petrilli testified, OAt this time its flame front was 50 yards wide and had traveled 50 yards from when we first noticed it as a spot. It was definitely push[ed] by high winds, approximately 35 mph. This was a very narrow spot in the canyon where the winds were also being funneled.O

At 1604 hours, Prineville Hotshot Jon Kelso, working the west flank below, radioed to Hotshot Supervisor Tom Shepard above that fire had spotted directly below the group working the ridge. Blanco immediately ordered all 22 ridge firefighters to the black area near Helispot 1. A wall of flame cut them off before they could reach their objective. They reversed direction, running for Helispot 2, followed by fire. Hotshot Louie Navarro said, OI saw huge black clouds and red glare. The people in front said they couldn?t make it to the black at H1. As we turned back, I stayed in the rear to make sure everyone was together and going in the right direction. As I was coming out, I was flanked on both sides by fire. Some firefighters were tired and wanted to deploy. As we moved down the ridge, I could feel the fire on the west side gasp for air and then just surge like a tidal wave…. It was hot and slamming against the ridge.O

Helitack crew members Richard Tyler and Robert Browning were working at Helispot 2. The fleeing ridgetop crew yelled for Tyler and Browning to follow them over the ridge and down the east drainage, leading to Interstate 70. Tyler and Browning instead chose another direction. Apparently they did not want to make an escape down a blind shaft. They ran north along the top of the ridge to a point above the jump site. There, fire cut off their escape to the east. The slope to the northwest was relatively flat, with rock outcrops, and they headed in that direction, flanked by fire. Another 150 to 200 yards beyond that, a steep, rocky, 50-foot-deep chute blocked their escape. They were overcome by fire and died.

The ridge crew, meanwhile, dropped into the east drainage?despite the fact that that side was beginning to burn?taking three separate routes to reach Interstate 70 safely. The east drainage was not a preestablished escape route. Blanco dropped into the east drainage and waited for firefighters coming off the hill. At 1611 hours, he reported to District Dispatch that he was losing the fire on the side toward the homes and needed air tanker strikes and EMS. An air tanker was dispatched at 1620 hours. Within 30 to 40 minutes the east drainage was consumed by the fire.

Longanecker was aware of the blowup just moments after it had occurred. He testified, OI knew that I needed to get to the safety zone. I could see in the bottom that it had crossed the canyon and [was] burning at a high rate of speed. Crossed over the canyon straight across from the double drainage. The fire spotted to the other side [west side of the drainage]. I could not see when it crossed back to the side I was on again. Then it was obvious that we needed to get out. I sent Tony up the ridge. We did not have a chance in brush patch. I was separated from the other jumpers.O Longanecker headed for the lunch spot, which he had already identified as a safety zone.

Mackey, concerned for the safety of the personnel working the west flank, descended the fireline during the initial moments of the blowup. At approximately 1610 hours he encountered Petrilli and members of the group that had been working the bottom of the fireline and directed them to head for the burned out area below Helispot 1; they already were on the way up seeking to distance themselves from the growing fire. Mackey then made radio contact with Longanecker, who indicated he was okay.

The eight firefighters working the bottom of the line above Longanecker, meanwhile, moved quickly up the hill toward the ridge, enveloped in smoke and flying embers and the roar of the fire. Partway up they dropped their equipment, recognizing the urgency of the situation. The wind was blowing so hard, they needed to secure their chinstraps to keep their helmets on. The fire was gaining on them. Petrilli recounted, OSoto and Woods were dealing with muscle cramps and dehydration. The noise of the firestorm in the canyon was like a jet during takeoff. The wind was still at 45 mph. Soto and Woods began to fall behind. I passed them, but kept encouraging them to keep coming and ensuring [sic] them there was good black up the hill. The area we were going through was black, but the aerial fuels were still there. I didn?t want to stay there because I just witnessed previously the hillside reburn with very high intensity. I still didn?t know what was going on with the fire below us. There was still very heavy smoke coming from below.O

Jumpers Soto and Woods quickly de-ployed their shelters approximately 200 yards from Helispot 1. The six others reached the safety area about 100 yards below Helispot 1, quickly cleared their areas, removed their chain saw chaps, and deployed their shelters. The wind made deployment difficult. Fire brands blew into the shelters. Between 1619 and 1621 hours, they radioed Mackey but received no response. At 1624 hours, they entered their shelters, where they remained for 11U2 hours, during which time they were in radio contact with Longanecker, who was safe at the lunch spot and did not have to deploy his fire shelter. All nine survived.

After contacting Longanecker by radio, Mackey moved up the west flank to account for members of the group working farther up the line. BLM Firefighter Brad Haugh stated that Mackey was requesting water drops about this time. Longanecker testified that Mackey Orequested a load of retardant. Dispatch asked if [the fire] was threatening houses. [Mackey] said we have a real bad situation here.O Two smokejumpers from the west flank, transporting equipment, already had reached the ridge just before the fire blew up; they escaped down the east drainage to the interstate highway.

Haugh and Kevin Erickson were at the upper part of the fireline. They had received word from Blanco to retreat down the east drainage but were waiting for Mackey and the 11 west flank crew members in case they needed help. Erickson and Haugh saw a spot fire ignite very close below the crew, which by this time was hiking back up the fireline toward the ridge?taking the fireline route because it was the only way out through the dense Gambel oak brush. Erickson radioed Mackey of the spot between 1614 and 1618 hours.

Haugh, in his testimony, described the situation: OI had the entire crew in sight at this time. It appeared to me that the crew was unaware of what was behind them as they were walking at what I considered a slow pace, tools still in hand, packs in place, and the sawyer still was shouldering his saw, the crew was still spaced about 5` apart. I shouted down OHey kids let?s pick up the pace and get the Hell out of here.? There was a slight ridge behind the crew which obscured our view of the bottom of the fire. The crew was walking through Gamble oak approx. 7` tall. As best as I can re-collect the fire roared behind the ridge, and that was the first indication of how bad it had gotten. Jumper Thrash made it to our location at the tree and said should we deploy? I replied no we have to make it over the ridge. The fire storm literally exploded behind the ridge with approx. 100` flame height. At this point I decided I had to run.O

Erickson stated, OThe spot grew quickly and I could see the hardhats above it. The spot moved fast. I did not feel a perceptible change in winds. I could tell that they were moving as fast as they could. At that time the lead guy and the group were 75 yards away. We were yelling at them to go faster. They looked tired and were not going fast. Thrash was in the lead and Mackey was second to the last. They were in a close group. At this time I asked Haugh pull out my camera. I took a picture. I saw them through the viewfinder with fire everywhere behind them. As I took the picture Haugh grabbed me and turned me around. I took one more look back and saw a wall of fire coming uphill.O

The fire exploded over the crew.

Smokejumper Hipke, in the west flank group, began running the last few hundred yards, passing two other firefighters. About halfway up the last pitch, he saw Erickson and Haugh yelling for the rest of the crew?about 30 yards behind Hipke?to drop their equipment and run. As Hipke ran, he tried to pull his shelter from its case. Erickson and Haugh turned and ran for the ridge as the fire, pushed by the violent winds, slammed up the hill. The blast of hot air knocked Hipke to the ground. Erickson and Haugh threw themselves over the ridge seconds before the fire exploded over them. Hipke tumbled after them. Haugh described the flame lengths as 200 to 300 feet about two or three seconds after he bailed over the top. The three ran 200 to 300 yards down the east drainage and stopped. Erickson and Haugh quickly attended to the second-degree burns to Hipke?s hands. The three made it to the highway.

Hotshots Jon Kelso, Kathi Beck, Scott Blecha, Levi Brinkley, Bonnie Holtby, Rob Johnson, Tami Bickett, Doug Dunbar, and Terri Hagen and smokejumpers James Thrash, Roger Roth, and Don Mackey died in the fire. Two of the firefighters had fully deployed their shelters; the rest did not. All crew members were carrying tools and packs when they stopped to deploy their shelters. Mackey was found second from the bottom, clutching the last firefighter as he tried to pull her up the hill.

Haugh testified, OIf [Erickson?s] camera survived it will show that the crew did not know [what] grave danger they were in. Despite what the photo may or may not show, I know in my heart that the 12 persons who died in that part of the fire were unaware of what was happening and did not have a chance to flee in time.O

POST-BLOWUP

After the blowup, resource commitment to Storm King Mountain intensified as officers in the agency command structure became aware of the disaster. Search and rescue efforts were initiated and retardant drops made on the fire. At approximately 1630 hours, the fire was first considered to have escaped initial attack. It must be noted, however, that soon after blowup even firefighters working at the helibase, while aware that shelters had been deployed, did not know there were fatalities. One firefighter, in fact, radioed District Dispatch at 1630 hours that they had a Omini-emergency.O Grand Junction Fire Control Officer Winslow Robertson took command of the fire at 1700 hours and established an incident management group of interagency fire managers and personnel. At midnight on July 6, a Type I incident management team assumed control of the fire. The fire was placed under control on July 11, after it had grown to more than 2,000 acres and threatened numerous structures.

POSTINCIDENT ANALYSIS

Fire potential. Fire behavior specialists conducted fire behavior predictions using computer models. The predictions were constructed using the tools and weather data available July 5. They were conducted primarily to provide a better understanding of the occurrence and to determine whether such methods could have been used effectively to the benefit of firefighting forces operating on Storm King Mountain.

The analyses indicate that rates of fire spread and flame lengths were in a range in which crowning, spotting, and major runs were probable for July 6. As such, fire control options were limited on that day. As stated, OThe predicted range of fire behavior is viewed as resistive to any direct means of fire control, and a handline [would not be] an effective control method.O

Data indicated that the chances of an ember?s causing a spot fire were 90 to 100 percent under forecasted weather conditions. The Oignition componentO?a measure of the potential for an ember to ignite a spot fire that subsequently will spread?as calculated at the Remote Automatic Weather Station (RAWS) in Rifle, Colorado (less than 30 miles from Storm King Mountain), was 100 percent. Calculations using fuel moistures and relative humidity indicated that a severe fire potential existed on Storm King Mountain. Furthermore, values for the Oburning indexO?in which comparisons are made between conditions on the date in question and weather stations? historical records on fire potential?were well above the high percentage threshold for weather stations in Rifle and Pine Ridge, closest to Storm King Mountain.

Actual fire behavior. Fire progression, directions, spread rates, and flame lengths also were studied. (See sidebar with accompanying graphics on pages 158-159.)

Survivability at entrapment locations.

1. Helispot 1 (shelter deployments?six 100 yards below Helispot 1, two 200 yards below Helispot 1): Temperatures from fire runs from the south were in the range of 300 to 800!F. These temperatures usually are not life-threatening even without a shelter, but radiant heat burns would be likely. Shelters in this area prevented radiant burns and considerably reduced smoke inhalation. One shelter deployed in this area showed no heat damage. Though not communicated as such to all firefighters operating on the scene, the black below H1 was correctly identified as a safety area.

2. Lower fireline smokejumper (line scout) at Olunch spotO: The smokejumper did not deploy a shelter and did not receive burns or suffer significant smoke inhalation. The grass in this opening did not burn. This area, like H1, also was correctly identified as a safe area earlier during operations.

3. Ridgeline: Temperatures on the ridgetop were below 1,200!F. A shelter dropped on top showed no damage. Packs and tools on the ground likely were ignited by ground fires after the flame front subsided. In the absence of ground fuels, shelter deployment at this location could have been successful.

4. Upper west flank: From their estimated location, the 13 crew members moved about 1,425 feet to where they were trapped. It is estimated they walked 1,108 feet in five minutes and ran the last 317 feet.

There was no mention of smoke hindering the breathing of these members. The firefighters had limited visibility through/over the Gambel oak, so they may have relied mostly on hearing to track the fire progress across the canyon below them.

A clear temperature gradient existed from the bottom of the entrapment site to the top of the ridge:

Y Six firefighters were found in a group 270 feet from the top. Temperatures there were in the 1,600 to 2,000!F range. This was not a survivable environment even in a fire shelter. Except for fire shelters, all items dropped on the ground were completely consumed. These six firefighters were caught fully in the flame front.

Y Five firefighters were found in a group 212 feet from the top, at the upper edge of the flame front. Two were able to get under their fire shelters, and three could not get theirs open in time. Temperatures at this level were in the 900 to 1,600!F range. Tools and items dropped here were melted or partially consumed. Fire shelters would have worked successfully in these conditions in other instances. Fire shelter failure likely was due to an interaction between the heat, which would cause delamination between the foil and glass cloth, and extreme turbulence, which would cause the foil to start cracking and then tear off in pieces. In addition, the two shelters were deployed perpendicular to the direction of the flame front. The shelter orientation increased the effect of the turbulence and the chance for flames to enter the shelters. Flames under the shelter can cause disintegration within seconds.

One firefighter?s shelter blew off from the foot end, turning inside out and exposing the firefighter to increased heat. Packs within the shelter contained fusees, which when touching the side of a shelter would easily ignite and could have melted the glass webbing hold-down straps. The occupant may have moved his feet up, away from the fusees, thereby releasing the shelter bottom. The fusees may have ignited after the shelter blew off or after the shelter disintegrated from the heat and turbulence of the flame front.

The second firefighter under a shelter also experienced complications. Evidence suggests that another firefighter to his left lifted the shelter off the ground and may have been partially under it. The original occupant rolled to his right, which would have lifted the left edge off the ground. Since the flame front was passing from left to right, flames likely would have entered the shelter. An alternative possibility is that failure of the left side of the shelter caused the occupant to roll to his right. It is not clear if conditions at this level reflect marginal shelter operational conditions or if human error contributed to the failure of the shelters.

Y One firefighter was found 121 feet from the top. Temperatures there were below 1,200!F with ground temperatures in the 300 to 600!F range?well within the survivability range for fire shelters under most conditions, though, as noted above, turbulence would have been a factor in successful deployment. The firefighter did not deploy his shelter.

Y The three firefighters who escaped over the ridge (Erickson, Haugh, and Hipke?Hipke being the only member of the upper west flank fireline crew to make it to the top) were assisted by the fire?s directional pattern: After the main flame front passed, the wind changed to straight uphill to the saddle. This crossing pattern gave the three firefighters extra time to escape before the fire turned back toward them.

5. Helitack crew: As Tyler and Browning headed north along the ridgeline, they passed through areas with high shelter survival rates. However, they left the ridgetop and headed northwest into a narrow chute with minimal survival chances. (Possibly, brush and smoke obscured the chute. From the ridge the land looks smooth and there is a large rock outcrop on the other side of the chute, which was likely their goal. Temperatures in the area in which they were trapped were in the 1,200 to 1,800!F range. Items dropped on the ground were completely consumed at the lower end of the site, with some partially consumed items near the top (40 feet away). Some dissipation of heat is apparent due to less charring on the trees farther up the chute near the rock outcrop. Both victims started to deploy shelters but were overcome by heat and smoke.

LESSONS LEARNED AND REINFORCED

– Wildfire response management at all levels must be continually reassessed. Program management and response capabilities must provide for effective fire control during heaviest expected activity?that is to say, a successful response management program is one that can handle the busiest July.

– Wildland fire programs must be adequately funded to the extent that adequate resources will help ensure the safety of suppression personnel and the public. Reduced budgets and staffing levels severely reduced the firefighting capabilities of the Grand Junction District, the Western Slope Fire Coordination Center (FCC), and similar agency branches. Fire management officers and agency managers testified that they could not adequately handle last summer?s fire activity with existing resource levels. The Grand Junction District, for example, did not have its own helitack team. The initial attack capability of the Grand Junction District consisted of two heavy engines and three light engines, with a total of 12 seasonal employees.

– Cooperation between agencies and branches is critical to effective wildland fire response. It was noted, for example, that conflict existed between the Grand Junction District and the Western Slope FCC?the District?s Oresource arm.O Managers of fire programs must ensure that agency/branch personnel understand and accept their responsibilities within the fire management systems. One manager testified that the District and FCC were Ocompletely separate operations.O

– Organizational operating procedures in wildfire management organizations should be reviewed and enhanced. Unclear operating procedures between Western Slope Fire Coordination Center and Grand Junction District fire organizations resulted in confusion about priority setting, operating procedures, and availability of firefighting resources, including initial attack resources. This lack of definition limited the effectiveness in the timing and priority of the suppression of the South Canyon fire.

– Officers with fire management responsibility must have the technical expertise to effectively manage their fire programs; for some managers, this expertise was lacking.

– Wildland fire managers must adopt and enforce proactive resource management. One BLM firefighter assigned to the Western Slope FCC with the function of ordering resources testified in the South Canyon Fire investigation to the hesitancy and conservatism of district fire management officers to preposition resources. He stated, OEveryone [is] too concerned about what it will cost….O The investigation statement made by BLM Colorado State Director Bob Moore reads, OBob is aware that some resource specialists and managers are reluctant to support aggressive initial attack actions. This is a fairly general attitude here (Colorado) as well as other parts of the Bureau. Except where managers have a heavy fire work load or managers have good fire experience and background.O

Despite the fact that the fire was in a fire exclusion zone and despite that on June 14 Grand Junction District management established a policy to suppress all new fires (that is, suppress instead of monitor new fires), sufficient resources were not brought into the fire/were not available until well into the fire. Smokejumper Longanecker stated, OI would make another situation that shouts watch out: [w]hen you don?t receive the resources that you need or you are debating with the dispatcher about the resources that you need. Needed more of everything on this fire.O

– Particularly during the height of the wildfire season, when weather conditions increase the risks assumed by ground fire suppression forces, personnel should not be committed to aggressive fire attack methods without the proper aerial support.

– Initial reports on wildfire activity may and often will conflict; however, err on the side of safety when assigning resources?that is to say, assume the worst-case scenario.

– Fire management officers must continually evaluate dispatch procedures and effectiveness. Here, too, budget reductions severely hamper effective communications. District Dispatch capabilities and procedures were not adequate for the extreme fire season and, specifically, the South Canyon Fire. For example, District fire orders for the South Canyon Fire were made as informal requests by telephone or in person to individuals in the Western Slope FCC. No records of these informal orders were maintained. On the night of July 5, the dispatcher on duty warned that overwhelmed communications capability would compromise safety.

-Wildland fire management officers and dispatchers must acquire an intimate knowledge of the physical characteristics of their jurisdictions that impact fire management and resource deployment decisions. The acting district manager for Grand Junction District indicated in his official statement that he Ohad no indication prior to 7/6 that this fire had much potential. He was always told that the fuels in that area were sparse.O Furthermore, personnel from Grand Junction District Dispatch expressed the belief that most fires involving pinyon-juniper fuels?the primary fuel during the early stages of the South Canyon Fire?do not exceed 100 acres in the area?an erroneous assumption that may have influenced dispatch decisions during the South Canyon Fire.

– With weather/fire conditions such a critical factor in wildland firefighting safety and effectiveness, it is imperative that all involved parties make efforts to provide and receive the most accurate weather information available. The South Canyon Fire underscores the following vital points:

-Weather briefings should include spot weather forecasts.

-The failure to transmit a red flag warning was a costly omission. None of the ground firefighters operating at the South Canyon Fire knew about a red flag warning.

-Red flag warnings should never be taken lightly by firefighting personnel, regardless of the regularity with which they are forecast in the days preceding an incident.

-All firefighting personnel must be briefed on weather forecasts both before arriving and once on the scene.

-Rely on weather forecasts that specifically describe wildland firefighting conditions, not NOAA forecasts designed for the general public.

-Modify strategy and tactics in deference to expected weather conditions.

-Establish and enforce a system whereby operating personnel are apprised of significant weather changes.

-The communications center must develop, interpret, and communicate information on fire weather, fire danger, and predicted fire behavior.

-All available weather station technology?in particular, fire behavior predictions using computer models?should be employed for real-life firefighting applications. A fire weather meteorologist assigned to the Western Slope FCC to give forecasts and briefings for specific wildfires was not used on the South Canyon Fire.

– Dispatching procedures and communications with the incident commander must provide a clear understanding of what resources will be provided in response to requests and orders.

– Dispatcher responsiveness to field forces is a critical factor in firefighting safety. Dispatchers must possess a level of training and experience, and communications centers must have the level of staffing, such that urgent fireground messages can be quickly identified and resources immediately assigned to address the first priority: protecting life.

-A direct-attack strategy must be constantly monitored and evaluated based on terrain, fuels, weather, resources, and other conditions, with firefighter safety the top priority. A point arrived during this fire, in hindsight, that Pulaskis and chain saws employed in a direct attack were not going to stop this fire. Strategic assessments and reassessments should be ongoing. Adjustments to the strategy, when necessary, should be made without hesitation by the incident commander.

– It is essential that safety zones and evacuation routes be identified prior to initiating the attack. Develop backup/contingency plans. Avoid situations in which there is one way in and one way out through heavy brush. Consider terrain in estimating evacuation times. Safety zones and evacuation routes were not adequately identified or communicated to personnel at the South Canyon Fire. Dense brush made the fireline the west flank crew?s only option. Longanecker stated, OUse of escape routes and safety zones prevent fatalities, not fire shelters.O

– Establish a strong on-scene command structure for which firefighter safety and accountability is the bottom line. Maintain effective and continuous fireground communications. Designate lookouts/safety officers to serve as the eyes of the incident commander. Ensure that fire activity is monitored at all times during the operation. At this incident, the ridgetop did not afford the incident commander with the visual perspective with which to make strategic evaluations. According to some firefighters, adequate communications were not achieved.

– There is and should be only one incident commander. Some firefighters were confused about who was making the strategic decisions at the South Canyon Fire.

– The incident commander must utilize all the expertise and information available to him in formulating and readjusting strategy.

– The incident commander must obtain and communicate to all operating personnel information on local fuels and OtypicalO fire behavior. Gambel oak was the predominant fuel consumed on July 6 in the rapid run ending in the fatalities; this fuel was recognized as a highly flammable and hazardous fuel type in the accident report on the 1976 Battlement Creek fire (in the Grand Junction District within 30 miles of the South Canyon Fire) that killed three firefighters. Smokejumper Erickson testified, OI have been in this situation before with unburned fuel below. Only other choice was to go indirect. I had never been in that type of fuel before. I know chaparral. This brush didn?t look so bad because it was a surface fire. I didn?t think it would burn because it was so green.O Other firefighters were surprised at the intensity of the fire through the underburned Gambel oak.

– The incident commander must assign a sufficient number of personnel to supervise fireline construction.

– Rest and rehab is a major safety consideration. The fatigue factor must be addressed. Postincident statements indicated that some firefighters first in on the fire were becoming fatigued and dehydrated. This can have serious implications when a quick retreat becomes necessary.

– Ongoing, periodic reconnaissance is essential. Aerial reconnaissance at this fire was inadequate. Acquire sufficient resources for this purpose: A helicopter employed in water drops and equipment lifts cannot and should not be expected to effectively double as a recon tool.

– Carefully consider the size of the fireline scrape in relation to aerial fuels. Question the effectiveness and safety of a fireline that in effect becomes a Ofire tunnelO should it fail to hold back the fire.

– The fireline must be safely anchored. As Smokejumper Petrilli stated, OThat is a very profound statement.O

– Train so that you can effectively deploy your last resort?your fire shelter. Two shelters were deployed perpendicular to the fire, compromising their effectiveness. Furthermore, it was noted that fire shelters were difficult to remove when suspended vertically under packsacks; firefighters could remove their fire shelters with one hand when they were mounted horizontally on their belts or mounted vertically on the side of the pack.

– The 10 Standard Fire Orders and the 18 OWatch OutO Situations must be used as an operating guideline on the fireground (see sidebar on page 162). Many of these precepts were violated at the Storm King Mountain incident.

RECOMMENDED FOLLOW-UP ACTIONS

The Report of the Interagency Management Review Team, South Canyon Fire, recommends extensive follow-up actions in response to the Storm King Mountain operation and includes a plan and time frame for their implementation. Some of these recommended actions are summarized as follows.

– Distinguish clearly between red flags for cold fronts and high winds and red flags for lightning. Key issues concern the possible decreased effectiveness through Ooveralerting,O terminology, and red flag criteria (i.e., local fire weather district vs. geographic coordination area).

– A fire behavior analyst should be available or requested whenever a fire weather meteorologist is requested for a fire coordination center. A fire behavior analyst can relate the weather forecast to how fires burn in terms of rate of spread, flame length, and fireline intensity. These are terms that firefighters understand.

– Fire weather forecasts must be communicated to firefighters on initial attack and extended attack incidents.

– Spot weather forecasts should be requested for fires that have potential for extreme fire behavior or exceed initial attack or are located in areas for which red flag warnings have been issued.

– NOAA Weather Radio forecasts should not be substituted for fire weather forecasts.

– A national interagency strategy and implementation plan should be developed to improve technical transfer of fire danger and fire behavior technology.

– The National Weather Service fire weather forecast program must be maintained at present levels to ensure firefighter safety.

– An organized live fuel moisture sampling network should be established for Gambel oak. Strategy and tactics should be adjusted on the basis of this information.

– Secure both short- and long-term strategies for institutionalizing a strengthened fire-safety sensitivity throughout the leadership and among employees in all agencies associated with wildland firefighting.

– Evaluate current training to ensure emphasis is placed on the basics of fire behavior, firefighting strategies and tactics, the 10 Standard Fire Orders, and the 18 OWatch OutO Situations.

– The South Canyon Fire incident should be used to develop a training exercise for agency administrators, fire managers, dispatchers, and firefighters. The training exercise should be developed by field-level firefighters.

– Develop mandatory fire shelter courses.

– Develop guidelines for adequate deployment sites and safety zones in different heat and flame scenarios to show the value and limitations of fire shelters.

– Fire behavior and fire weather concepts should be reviewed in training each year for all fire managers.

– Conduct a management review of the Fire and Aviation Programs for the BLM State of Colorado.

– Implement the National Wildfire Coordinating Group?s work, rest, and rotation guidelines.

– Develop a mechanism to study and learn from wildfire operations conducted by other organizations/agencies.

– Incident meteorologists should be ordered as part of each Type I team?s standard order during wildfire incident mobilization.

– Develop a standard format for spot weather forecasts.

– Review major aspects of smokejumpers and hotshots programs.

– Develop interagency courses for agency administrators and senior incident management personnel.

– Match the qualifications of incident commanders with the complexity of fires during all phases of suppression operations.

– Develop minimum qualifications for fire managers and agency administrators.

– Evaluate the coordination/dispatch system.

– Fuels management, especially through the reintroduction of fire as an integral part of natural resource management, must be a high priority for the Department of the Interior and the Department of Agriculture.

– Develop policies that define the appropriate role for federal wildland firefighters in protecting structures and communities in the wildland-urban interface.

|

(Photo by Dennis Schroeder, Rocky Mountain News.)

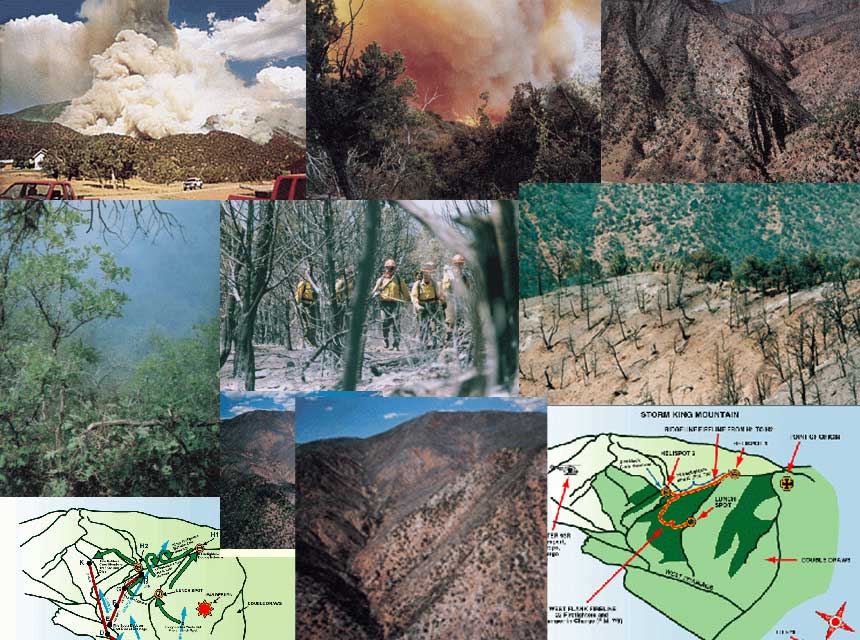

Storm King Mountain reaches approximately 7,000 feet above sea level. A ridge running roughly in a north-south direction was the focal point of fire operations. This ridge was flanked by two steep, rocky canyons (drainages). The fire ignited on July 2 occurred in the west drainage, approximately 1,000 feet in elevation below the ridge line.

The topography of the area was a significant factor in the incident. Topographical characteristics included steep and rugged fire terrain, with approximately 50 to 100 percent of the land area being slopes and with gullies and ravines narrowing sharply at their bottoms and an area configuration such that the fire burned on all aspects. Fire elevations at approximately 1600 hours on July 6–the time of the blowup–ranged from 5,980 to 7,000 feet.

Fuel characteristics also were major factors in the incident. Fuels included pinyon-juniper brush, Gambel oak, and a variety of grasses. The pinyon-juniper and grasses sustained the fire in its first three days of growth. The Gambel oak, six to 12 feet high, was prominently involved in fire on July 6–the day of the disaster. It existed in this area in large sections at higher elevations on the ridge; these sections were extremely thick and difficult to walk through. Gambel oak is recognized as a highly flammable, hot-burning fuel and has been a factor in other wildland firefighter fatalities. Moisture content in the vegetation, as would be expected in drought conditions, was very low. n

RED FLAG WARNINGS

The National Weather Service issues red flag forecasts to alert fire agencies of the potential for high to extreme fire danger and critical weather conditions. A red flag forecast indicates that a red flag event has a strong potential to occur within 12 to 72 hours. The Denver Fire Weather Office generally issues a red flag forecast when high to extreme fire danger conditions are combined with one or more of the following weather conditions:

- a significant increase in wind speeds–specifically, sustained winds of 20 mph with stronger gusts;

- a dry thunderstorm outbreak with significant lightning activity;

- a significant decrease in relative humidity;

- a significant increase in temperature;

- the first episode of thunderstorms after a hot, dry period;

- a Haines Index of 6 (see below); and/or

- any combination of weather and fuel moisture conditions that in the judgment of the fire weather meteorologist would cause extensive wildfire occurrence.

Between June 1 and July 6, 1994, the Denver Fire Weather Office issued 10 red flag warnings for the Grand Junction BLM District, including consecutive warnings for July 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. The red flag warning for July 6 was unique, however, in that it was issued for strong winds associated with a cold front; the other warnings were for a combination of dry lightning and low relative humidity.

The Haines Index measures how atmospheric stability contributes to the growth of wildfires–most specifically the key factors of moisture (relative humidity) and air currents. A Haines Index value of six correlates to a high potential for extensive fire growth. n

|

|

(Above) A view of the west flank. The west flank fireline, starting at the ridge (left of photo) and running south to what was known as the “lunch spot,” is visible. A firefighter waited out the firestorm at that location. At approximately the highest point of the ridge is Helispot 1. Eight firefighters deployed shelters in a black area just below the helispot and survived. (Above right, right) These photos offer two views of Storm King Mountain and the west drainage.

|

|

|

(Left) The flame head of the blowup raced along the west side of the west drainage, then jumped back over to the east side, spotting at the bottom of the drainage directly below the retreating firefighters on the upper west flank fireline. This photo shows the fire as it is beginning its move up to the west flank. (Right) The blowup between 1630 and 1700 hours.

|

The east drainage down which fleeing firefighters escaped to the highway. Not long after they reached safety, this blind shaft was consumed in fire.

On the afternoon of July 6, the fire was active all along its perimeter in the pinyon-juniper fuel. It continued to back down the slope and make short runs with occasional torching of trees. Starting at 1543 hours, the fire made several runs in the burn south of the lunch spot. Three smokejumpers observed the reburn of underburned pinyon-juniper and Douglas fir forest, reporting 100-foot flame lengths in the flare-up within the previous burn.

At 1600 hours, as the winds reached their highest velocities, the fire reached the bottom of the west drainage. It crossed from the east to west sides of the drainage at point A (see graphic), then spread rapidly up the west side (points B, C, and D). The fire then jumped back across the drainage at point E, below the crew that was walking out the fireline to the ridge. The spot fire moved from sparse pinyon-juniper and Gambel oak with a grassy understory to dense green Gambel oak on a slope that steepened to 50 percent (points E to G). Racing up the slope, the fire was influenced by stronger winds of 45 mph, moving quickly through underburned Gambel oak just above the west flank fireline to the ridge (points G to H), overtaking the 12 firefighters located approximately between points I and J.

During the run, its calculated rate of spread from the pinyon-juniper to the green Gambel oak accelerated from 3.1 to 10.7 mph. The rate of spread through the underburned Gambel oak may have been as high as 18.5 mph. Smokejumper Kevin Erickson, about 210 feet below the ridgeline, estimates that it took 30 seconds for the spot fire to move to the ridgeline, but the physical evidence and the fire behavior put the time closer to two minutes.

The fire continued to move up the west drainage. It took approximately seven minutes for the fire to travel from points D to K, the point at which Firefighters Tyler and Browning were overtaken by the fire. n

|

|

|

|

|

(Left) The Gambel oak on Storm King Mountain was very dense and continuous. It was a major factor in the violent fire behavior on July 6. (Below) These photos taken during mop-up of the South Canyon Fire illustrate the fuel and terrain challenges firefighters faced on Storm King Mountain. (Photos by Nathan Bilow.)

THE 10 STANDARD FIRE ORDERS

1. Fight fire aggressively, but provide for safety first.

2. Initiate all action in response to current and expected fire behavior.

3. Recognize current weather conditions and obtain forecasts.

4. Ensure that instructions are given and understood.

5. Obtain current information on fire status.

6. Remain in communication with crew members, your supervisor, and adjoining forces.

7. Determine safety zones and escape routes.

8. Establish lookouts in potentially hazardous situations.

9. Retain control at all times.

10. Stay alert, keep calm, think clearly, act decisively.

THE 18 “WATCH OUT” SITUATIONS

1. Fire not scouted and sized up.

2. Country not seen during the daylight.

3. Safety zones and escape routes not identified.

4. Unfamiliar with local weather and local factors influencing fire behavior.

5. Uninformed on strategy, tactics, and hazards.

6. Instructions and assignments not clear.

7. No communications link with crew members and supervisors.

8. Constructing a fireline without a safe anchor point.

9. Building fireline downhill with fire below.

10. Attempting frontal assault on fire.

11. Unburned fuel between you and the fire.

12. Cannot see main fire and are not in contact with anyone who can.

13. You are on a hillside where rolling material can ignite fuels below.

14. Weather is getting hotter and drier.

15. Wind increases or changes direction.

16. Spot fires frequently cross line.

17. Terrain and fuels make escape to safety zones difficult.

18. Taking a nap near the fireline.