BY BILL GUSTIN

Success in conventional forcible entry depends on the strength of firefighters and their knowledge and skill in forcible entry techniques. Success also depends on using the right tools for the job: a sledgehammer, a halligan-type tool, and a flathead ax. The need for all three tools is explained in “Tips for Improving Effectiveness in Forcible Entry” (April 2008). Experienced firefighters can recognize a door that can be forced by conventional techniques and those that call for power tools or “through-the-lock” methods. Firefighters experienced in forcible entry also know when they are fighting a losing battle with tools and techniques that are not working and know when to stop and try something else. In this article, I will focus on forcing doors by conventional techniques—that is, the use of hand tools to pry and strike.

FORCING INWARD-SWINGING DOORS

You can identify inward-swinging doors (doors that open away from firefighters performing forcible entry) by the absence of hinges. Some training materials state that an inward-swinging door can also be identified by its being recessed three or four inches into a wall. This indicator, however, is not reliable, because both inward- and outward-swinging doors can be recessed in a masonry wall. This can be seen in the photos of forcing an outward-swinging door in this article; the door is recessed three to four inches in a concrete block wall.

Before we look at techniques for forcing inward-swinging doors, let’s review some terminology that should be common knowledge for all firefighters. A swinging door closes against a stop, or a rabbet, on the top and sides of a doorjamb. Although a stop and a rabbet serve the same purpose, they are different. A stop is a strip of wood approximately 1⁄2-inch thick that is nailed to a wood doorjamb; it is commonly found on interior doors, such as bedroom doors. A rabbet is more substantial than a stop, because it is an integral part of a doorjamb that is one piece. A rabbet is the shoulder approximately 1⁄2-inch thick that is milled into a wood doorjamb and is commonly found on exterior doors. Steel doorjambs are usually fabricated with a rabbet and are seldom fitted with a stop.

Additionally, doors may close against a threshold at the bottom of a doorway. You can see a stop or rabbet from the outside of an inward-swinging door; it helps firefighters identify the door as inward-swinging. The stop or rabbet is the part of the doorjamb that covers the gap between the door and the jamb about 1⁄2 inch. Weather stripping is often fastened on the stop or rabbet and threshold of exterior doors. A stop or rabbet prevents firefighters from inserting a pry tool directly between an inward-swinging door and its jamb. A door without a stop or rabbet could continue to swing past the point when its lock bolts and latches line up with the doorjamb. This would exert leverage on the hinges that could tear them out of the doorjamb.

When teaching forcible entry, the question inevitably arises, “Why don’t we just kick or bash in the door?” As a practical matter, kicking or battering a door with a sledgehammer may be the simplest and fastest way to gain entry through an inward-swinging door. You can force some inward-swinging doors by striking them with a sledgehammer near their locks or hinges. Striking an inward-swinging door may be effective alone or in conjunction with the prying actions of a halligan.

I can remember when our ladder apparatus carried a battering ram. I also remember that it was extremely heavy, but I can’t ever remember a fire where it was used. It can be difficult to deliver a powerful kick or batter a door when encumbered in full protective clothing. That’s why police and S.W.A.T. team members have more success with this method than firefighters. Additionally, firefighters have injured their legs and knees kicking a door that will not yield. Remember, a door that you kick or batter in can swing open uncontrollably unless you control it with a rope or a strap.

Forcing an inward-swinging door with a halligan is more meticulous and less strenuous than attempting to kick or batter it in.

Techniques

The first techniques is using an adz and the spike end of the halligan to exert a shear or pushing force against a door. The techniques for using the adz and the spike can be used alone or in conjunction with the fork.

Remember that the construction of a door’s jamb is an important factor in a door’s forcible entry size-up; it can influence the choice of tools and techniques. If you find a wood doorjamb in your size-up, you can use your sledgehammer or an eight-pound ax to drive the halligan’s adz or spike into the wood jamb behind its stop or rabbet, a few inches above or below the lock (photo 1). The objective here is to use the adz or spike imbedded in the wood doorjamb as a wedge and a fulcrum, transferring force against the door. Pushing the shaft of the halligan in a downward direction, then inward toward the door, exerts considerable force (photo 2). “Should I drive the adz or spike into the jamb?” you ask. That depends on which side of the door the knob, locks, and latches are and how your halligan is configured.

Using my department’s halligan, the spike is driven into the jamb when the lock is on the right side of the door (photo 3), and the adz is imbedded when the lock is on the left (photos 1-2). When the adz is imbedded in the jamb, the spike forced against the door may puncture or tear a lightweight wood or foam-filled metal covered door. You can prevent this by placing an ax blade flat between the spike and door to increase its surface area (photo 4).

Once you have gained an initial purchase with this technique, drive the spike or adz right above the lock cylinder. Downward movement on the tool will apply considerable shear force directly on the lock.

One firefighter may be able to force an inward-swinging door set in a wood jamb by himself, using only the halligan. The key is to swing the halligan like a baseball bat to imbed the spike or adz into the doorjamb. If conditions allow the firefighter to stand, he should put his shoulder into the door as he pushes inward and downward on the shaft of the halligan.

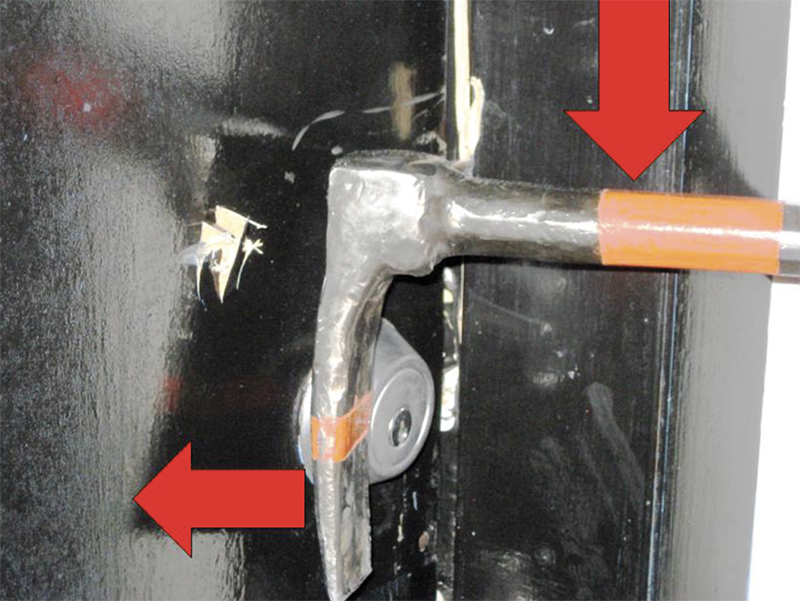

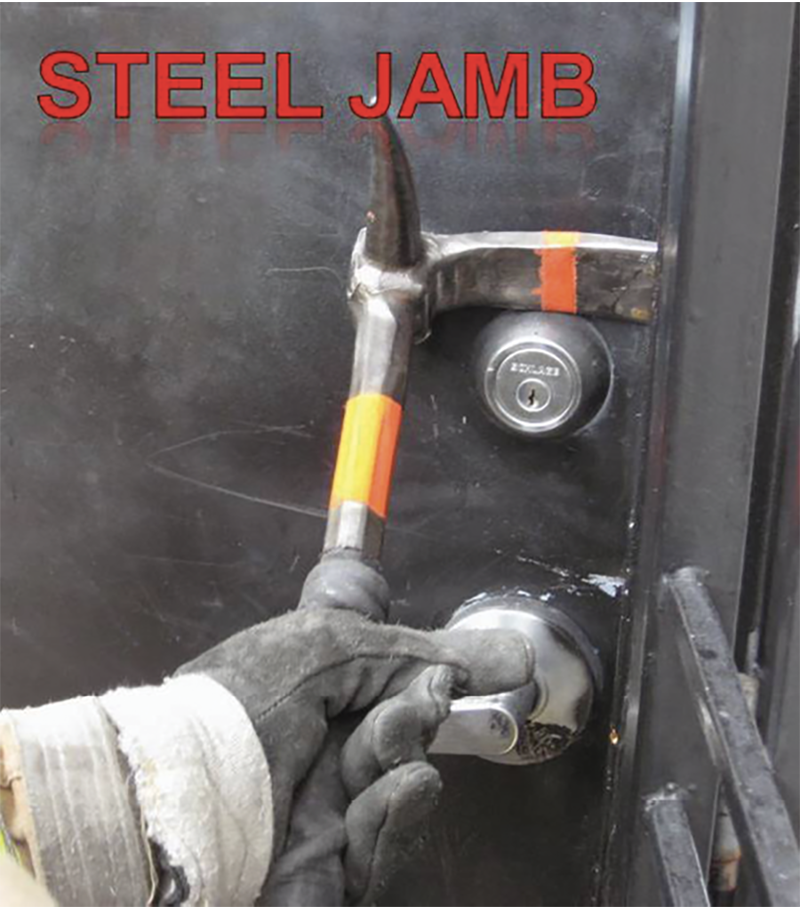

Now, what if you should encounter an inward-swinging door set in a steel jamb? In this case, it is unlikely that you can imbed the adz or spike into a substantial steel jamb, but you can still apply considerable shear force to the door. Your objective is to insert the adz behind the steel rabbet a few inches above or below the lock or between locks if there is more than one (photo 5). Often, it is possible to set the adz by simply tapping it in place with the palm of a gloved hand.

Inserting the adz behind the rabbet provides only about 1⁄2 inch of purchase, the thickness of the rabbet, but that may be sufficient to apply significant force against a door. Pushing the shaft of the halligan downward rotates the adz, forcing it to widen the gap behind the rabbet and the door (photo 6). Often, this is sufficient to force steel doors locked with only a doorknob latch. If your first attempts do not force the door, reposition the adz directly over a lock cylinder (photo 7). Now the lock cylinder acts as a fulcrum, increasing leverage when the shaft of the halligan is pulled toward the door. This works well with the hotel room key-card locks because their large profile can provide a significant fulcrum and leverage effect.

There is another technique involving the adz of a halligan that you can use when an inward-swinging door is secured with a surface-mounted sliding “L” dead or barrel bolts. Often, these devices are mounted at the top or bottom of a door. Firefighters who force the main lock may find that some other device is still holding the door closed. In this case, maintain the gap between the door and the jamb at the main lock by inserting an ax blade. Then position the adz on the inside of the doorjamb and pry downward and inward, working toward the surface latch or barrel bolt (photo 8).

Will the preceding techniques work on every door? Of course not. There is no forcible entry technique that guarantees success every time. But firefighters who fail to force a door by using the adz and spike end of a halligan have not wasted their time, because those techniques almost always result in crushing the door and jamb, providing a gap into which you can insert the fork of the halligan.

USING THE FORK

A “true” halligan has a fork that is tapered and slightly beveled, or curved. Once you drive the fork deeply between the door and the jamb with the bevel or outward curve toward the door, the bevel will act as a fulcrum, increasing shear force against the door when you push the shaft of the halligan inward toward the door. The spreading of the fork and the shear imparted by the bevel attack a door with force in two directions.

To begin this technique, place the fork, with the bevel toward the door, a few inches above or below the lock or in between locks. Start with the shaft of the halligan at about a 45° angle from the face of the door. Now tap the adz end of the halligan with a flathead ax or sledgehammer to push the tip of the fork behind the rabbet or stop. Once the tip of the fork is set, pull the shaft of the halligan slightly away from the door, and strike the tool with vigor. After each strike, pull the shaft farther from the door. This allows the fork to work its way past the edge of the door. To be successful, you must continually move the shaft of the halligan away from the door as you drive the fork deeper between the door and the jamb (photos 9-10). If you encounter a metal door in a tight-fitting metal jamb, it will be almost impossible to drive the fork with the bevel toward the door. In this case, rotate the fork so that the bevel is away from the door, and reposition the shaft of the halligan so that it is parallel to the face of the door. With most halligan-type tools, the tip of the adz will touch the door when the halligan is in this position. Now the curvature of the fork makes it easier to drive or “wrap” it around the edge of the door (photos 11-13). Once you have gained a sufficient purchase by crushing the door and the jamb, rotate the fork so that the bevel is again toward the door (photos 14-15), and continue driving in the fork and pulling the shaft away from the door.

Now consider a tight inward-swinging metal door that is recessed in a masonry wall, an alcove at the entrance door of a garden apartment or at the end of a narrow hallway. This can interfere with driving the fork with the bevel away from the door, because when the shaft of the tool is parallel with the door, the adz end will be a few inches from a wall. This restricts the swing of a sledgehammer or ax when striking the adz end of the tool. This can necessitate striking the “shoulder” of the fork until the shaft of the tool can be pulled away from the door enough to bring the adz end within striking range. If a door is recessed in a masonry wall, consider using a sledgehammer to break out brick or block that is interfering with striking the halligan. Once the shaft of the halligan is 90° to the door (photo 9), continue to strike the tool to drive the fork in further until it is one to two inches inside the doorjamb (photo 10). Then pry the door open by pushing the shaft of the halligan toward the door; put two firefighters on the tool to exert more force. Attempting to pry a door before the fork is deep enough in the jamb will usually result in its slipping out of its purchase point.

To gauge depth, grind a notch or paint a stripe on the fork of the halligan. Some departments mark the fork 1½ to 1¾ inches from the end. This indicates the average thickness of a door. (The actual thickness of doors ranges from 13⁄8 to 17⁄8 inches.) I know of an ambitious company that paints a stripe 3½ inches from the tip of the fork. This allows for the thickness of most doors between 1½ and 1¾ inches and as much as two inches of fork in contact with the inside of the doorjamb.

VICTIM BEHIND THE DOOR

Firefighters gaining entry through an exterior door or opening interior doors for search may find a victim directly behind the door. Statistics tell us that a significant number of fire victims are found in exit paths. That’s why firefighters are trained to quickly search the area around and behind a door.

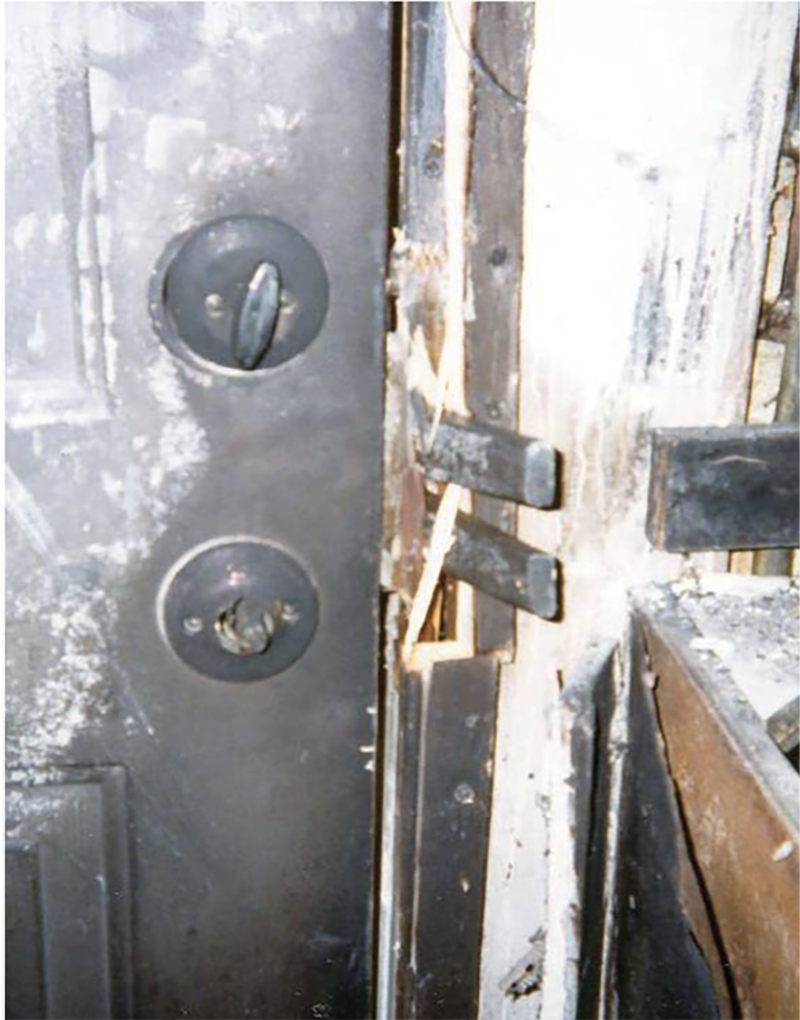

The fear of home invasion has caused residence owners and occupants to install one or more deadbolt locks on their doors, usually a “double deadbolt.” A double deadbolt lock does not have, as its name implies, two deadbolts; it has two lock cylinders, one on each side of the door. Double deadbolt locks may lock out intruders, but they also lock occupants in their residence, requiring them to use a key to escape a fire. In my company’s district, double deadbolt locks and iron security bars are the norm, not the exception. It is not uncommon to find residence doors and iron security gates equipped with two double deadbolt locks, each requiring a different key. This can require as many as four keys to exit. As a result, residents attempting to escape a fire may pass out from the smoke before they can find their keys or collapse behind the door they were attempting to unlock. An unconscious victim behind an inward-swinging door is a real problem.

Firefighters performing forcible entry may find a door that opens just a few inches, because it is blocked by an unconscious victim. Unless another entrance can be found, such as another door or a nearby window, you will have to cut the door with a power saw or “lay it down” by forcing it at its hinges. A size-up that determines whether a door has a steel or wood jamb will indicate the tools and techniques necessary to force an inward-swinging door at its hinges.

Firefighters in this situation should consider themselves very lucky if they find a wood doorjamb. In this case, you can drive the adz or spike of the halligan, depending on which side of the door the hinges are located, into the jamb, near the door’s uppermost hinges (photo 16). The adz or spike imbedded in the doorjamb acts as a fulcrum when you pull down the shaft of the halligan, forcing the adz or spike against the door, separating it from the top hinge. Striking a door at its hinges with a sledgehammer is also effective; this can be done alone or to hasten the prying action of the halligan. As explained earlier, when the adz is imbedded in the doorjamb, the spike may puncture or tear the door. If this occurs, position an ax blade between the spike and the door (photo 4).

Once the top hinge fails, insert an ax blade in the gap at the top of the door. Now, use the adz or fork to pry the door, working downward toward the second hinge (photos 17-18). Once the second hinge fails, push at the top of the door; its leverage will tear out the bottom hinge. Be sure to control the falling door with a rope or strap hitched to the doorknob so that it does not injure the victim.

Firefighters encountering a victim behind a heavy steel door in a substantial steel jamb will face an extremely difficult and time-consuming task if they must force the hinges conventionally. Firefighters facing this challenge should call for a hydraulic forcible entry tool to pry a door from its hinges and, if smoke conditions permit, a metal-cutting rotary saw to cut the hinges.

OUTWARD-SWINGING DOORS

Doors that swing outward, toward the forcible entry team, are readily identified by hinges that are visible and accessible. This brings up the question, “Why don’t we just pull the hinge pins?” Pulling the hinge pins may be the best method to gain entry when the urgency of the situation does not require rapid entry and does not justify damage.

Forcing a door from its hinge side doesn’t always work. Hinge pins are commonly spot welded in place or secured by an allen set screw that is not accessible when the door is closed. And, cutting the hinges does not ensure success.

Years ago, I ordered my company to cut the hinges of a door at the rear of a commercial building. Now, I thought confidently, we can easily pry open the door from the hinge side. My confidence changed to embarrassment when we failed after repeated attempts. We later found that this door had large masonry nails driven into the edge on the hinged side. When closed, these nails fit into holes drilled into the doorjamb. I was naive to think that a businessman would spend a lot of money on a heavy door and several locks but leave the hinges vulnerable.

To force an outward swinging door with a halligan, begin by driving the adz between the door and the jamb a few inches above the lock or between locks if there is more than one (photo 19). Make sure to position the halligan with its fork toward the hinge side of the door. This allows the slight curvature of the adz to help it work its way around the edge of the door.

Gaining the initial purchase between the door and the jamb can be time consuming with a strong, tight-fitting steel door. Widen the gap between the door and jamb by driving an ax blade in the space with a sledgehammer. This will allow for easy insertion of the adz.

It is important to drive the adz to a depth equal to the full thickness of the door—that is 3⁄8 to 1¾ inches. If, in your haste, you drive the adz to an insufficient depth and then attempt to pry the door, you may end up tearing a wood door or “skinning” a metal-covered door, leaving the lock latch and bolt intact. Conversely, if you drive the adz deeper than the thickness of a door, it will become imbedded in the doorjamb, making the task of prying the door more difficult.

Judging how far to drive the adz is usually not a concern with a door set in a substantial steel jamb. Experienced firefighters are attuned to the sound of the ax or sledgehammer striking the halligan; the metallic “clang” will change to a solid “thud” when the edge of the adz makes contact with the steel doorjamb. To ensure proper depth, fire departments may grind a notch or paint a stripe on the adz 1½ to 1¾ inches from the tip, indicating the average thickness of the door (photo 20).

Once you drive the adz to the full thickness of the door, pull the shaft of the halligan away from the door. Don’t hesitate to put two firefighters to work on the tool. If the door does not pry open, use the weight of two firefighters to push the shaft of the halligan down. This action will rotate the adz, increasing the spread between the door and the jamb and, hopefully, crush the door and jamb sufficiently to allow the slightly curved adz to work its way around the edge of the door (photo 21). Now you can drive the adz to its maximum depth, achieving greater leverage (photos 22-24).

If these techniques fail, you have not wasted your time, because the adz will crush the door and the jamb, allowing for easier insertion of the fork.

When driving the fork between an outward-swinging door and its jamb, position it with the bevel against the doorjamb. This will allow the curvature of the fork to work its way around the edge of the door.

Leverage exerted by the fork of a halligan can be limited when a door is recessed in a masonry wall, because the shaft of the tool strikes the doorway, restricting its range of motion (photo 25.) Again, this is another reason to always take a sledgehammer along with the irons. A company that encounters an outward-swinging door recessed in a masonry wall may be able to use its sledgehammer to break brick or concrete block out of the doorway, allowing room for the shaft of the halligan.

The fork, however, may be of no use when an outward-swinging door is recessed in an alcove, which is common in garden apartments or at the end of a narrow hallway, because a wall restricts the prying movement of the halligan. Experienced firefighters will recognize this obstacle to conventional forcible entry and, on encountering a strong recessed outward-swinging door, may call for a metal-cutting rotary saw to cut lock bolts, latches, and hinges if smoke conditions allow the operation of its gasoline engine. Success in conventional forcible entry depends greatly on the proper positioning of tools. Questions such as “Should we begin forcing this door with the adz or the fork?” and “Should we place the bevel of the fork toward or away from a door?” can be answered during prefire planning and company drills. Fire companies should frequently select buildings in their response district and determine the proper tools and techniques necessary for fast and effective forcible entry in these structures.

Some fire companies seldom get a chance to practice hands-on forcible entry because acquired structures scheduled for demolition can be rare, especially in relatively new, suburban communities. Additionally, forcible entry training simulators may be beyond a small fire department’s limited budget. Firefighters fortunate enough to find a door on which to practice forcible entry should maximize this valuable opportunity. You can force one door several times by wedging it closed by driving a flathead ax under the door. This will provide enough resistance for firefighters to repeatedly practice tool positioning and prying techniques.

BILL GUSTIN, a 35-year veteran of the fire service, is a captain with Miami-Dade (FL) Fire Rescue and lead instructor in his department’s officer training program. He began his fire service career in the Chicago area and teaches fire training programs in Florida and other states. He is a marine firefighting instructor and has taught fire tactics to ship crews and firefighters in Caribbean countries. He also teaches forcible entry tactics to fire departments and SWAT teams of local and federal law enforcement agencies. Gustin is an editorial advisory board member of Fire Engineering.