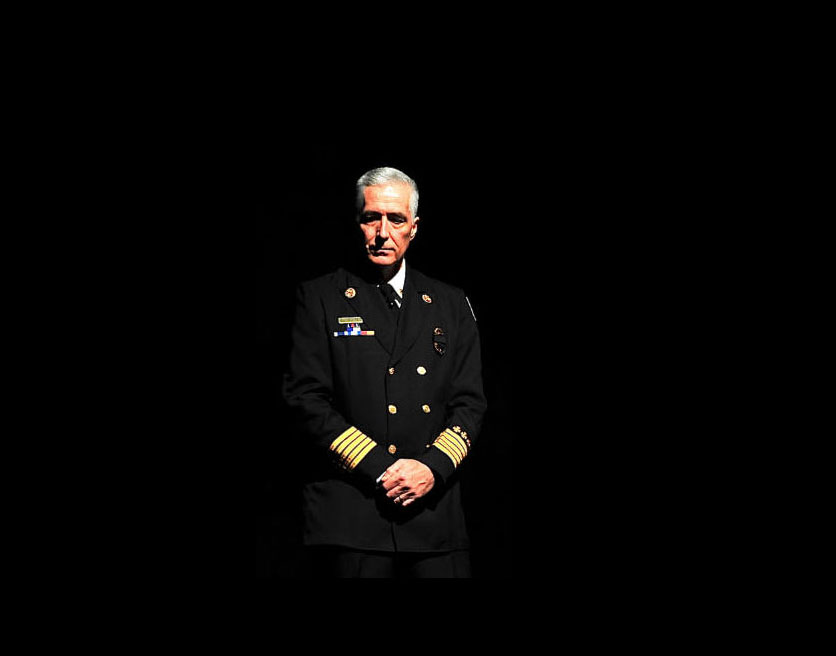

editor’s opinion ❘ By BOBBY HALTON

I am friends with a pilot who owns an exact replica of a 1919 airplane. He is comfortable flying it. He is careful to do so only in perfect weather and is very aware of its limitations should any component of it fail.

Being comfortable most of the time is a good thing—being comfortable with your assignment, with your tools, with your crew. There comes a time when comfort starts to drift into a sense of wellness that may or may not reflect reality.

We do many things without thinking consciously about them. We do many things that we only review reflecting on parameters that we have set as benchmarks such as the NIOSH 5. Chief Alan V. Brunacini once wrote in May 1967: “Don’t be afraid to make changes. If something has been done in a particular way for 20 years, that alone is often a sign that it is being done wrong.” Now, there are a lot of exceptions to the good chief’s rule, like issues of fidelity and honor, but with regard to operations, testing, or procedures, maybe the 20-year rule should always be a time to reassess.

RELATED

Unlike Wine, Fire Tests Don’t Get Better with Age

Construction Concerns: IBC 2021 Heavy Timber Proposal

Humpday Hangout: The ‘Vertical Lumberyard’

When we apply a set of measurements to determine if a process or a procedure is getting us the best effect or the best usable information, we do so at a point in time. At any point in time, our knowledge is restricted to what is known. So, how we assess something or how we measure something needs to change with time. Testing of building materials, construction elements, and assemblies must continuously evolve because, over time, things change, especially when they have to do with our physical environment.

We are currently engaged in a great deal of research and testing. These tests involve the “modern” fire environment—modern, in this case, referring to the incredible expansion of polymers in almost every aspect of our construction.

The research and testing are being done not only on the products and materials that are burning but also on our methodology in extinguishing these materials. This is a good thing. This research should be disseminated widely among our firefighters so that those who have skin in the game can determine what the research and testing reveal.

We are learning about flow paths, the effects of ventilation, and the length of time we can expect the floor to withstand fire or the roof to withstand flame impingement. The testing has been on scale models, in the real world, and continues today. This is excellent, good experience. Firefighters will use this information in a wide variety of ways, in ways that engineers could never imagine. The real world is often very messy and very complicated, and that’s where the expertise of a good firefighter is always the gold standard.

What is of real interest is that the most important test in fire protection that assesses the fire resistance of building components on fire is now roughly 100 years old—that’s right, the very test that assesses the integrity of beams, columns, roofs, and walls under fire attack in the same buildings where we are looking at the most minute details of flow path, transitional attack, interior aggressive attack, and vent-enter-isolate-search. We wisely spend millions of dollars of grant money to understand the relationship of firefighting and fire behavior, but it is all predicated on a “building” fire test developed 100 years ago.

We have published several excellent scholarly articles in Fire Engineering about this dilemma. We have had conversations with our friends at Underwriters Laboratories who are involved in this testing about American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) E-119, Standard Test Methods for Fire Tests of Building Construction and Materials, a test that has remained relatively unchanged for 100 years. In essence, we are more concerned about opening a door or breaking a window than we are about the fire resistance of the building we are fighting a fire in and, by extension, the likelihood of its collapse. With more and more innovation in building materials to include laminated “mass timber,” it’s time for the fire service to become much more vocal about having these building materials/engineered materials tested in full-scale and more realistic environments.

The current test had significant limitations when it was first designed. There was no void space in floor systems; today’s fires starting inside a lightweight wood truss floor’s void spaces are a reality. The century-old test was designed at a material span limitation of 17 feet; today, we have materials that span a great deal more than 17 feet. Fire protection engineers and safety engineers have pointed out that the fireproofing applied prior to the testing was also done perfectly and does not reflect how it may be done in the real world. These concerned folks also point out that the connections between floors and walls and elsewhere in buildings are not tested. Perhaps the most insidious problem is that beams, columns, walls, floors, and roofs are tested individually—not as an assembled, actual building. Imagine if we tested planes that way!

So, while the fire service is thoroughly engaged in evaluating our tactical and procedural approach to structural firefighting, the very battlefield where we conduct those firefights is not undergoing the same rigorous evaluation and study. Several major fire service groups involved with construction and codes have been lobbying aggressively for better testing and alternative language. So far, their concerns have gone unheeded. This could be for many reasons—financial, procedural, or a perceived lack of interest from the general fire service itself. We don’t think that is the case at all. What we think is that we are not sure how to have our voices heard.

American firefighters want buildings and their structural systems to be studied under modern fuel loads. We want these structural systems tested as a complete building, not individual pieces. We want that research communicated to us so that we can better evaluate areas of refuge and evacuation routes and have a greater sense of understanding regarding collapse and failure. As firefighters, we understand that nothing is perfect: All buildings can fail, all systems can fail, and so we are not asking for perfection. But, what American firefighters are demanding is realistic, accurate, and full-scale testing of modern buildings and their complete structural systems.

We admire old aircraft, but we shouldn’t travel with our families on them. We can admire old testing methods, but we shouldn’t bet people’s lives or ours on them.

MORE BOBBY HALTON