As Truck 2 drove to the hospital to pick up its personnel who rode with Medic 2 to assist with patient care, Captain Jones could not help but think how oddly the patient had reacted to the care provided. In his 17 years of experience, he could not ever remember defibrillating a patient more than 10 times. Even the antiarrhythmic medications they administered had not helped. The patient stayed in ventricular tachycardia the whole time, initially with a pulse; but they lost that after the third shock. Hopefully, Jones thought, the patient would start responding to treatment on the way to the hospital.

As soon as Jones walked through the emergency room doors, he knew something was wrong. This place is never this quiet, he thought. The staff avoided eye contact with him. What was going on? Then he found his personnel. Firefighter Cruz was pale and looked as if he was about to vomit. “We shocked a paced rhythm,” he blurted out.

What? How could this have happened? Jones wondered. How could his crew mistake a paced rhythm for ventricular tachycardia? They were better than that. The more he thought about it, the madder he became at his crew. This is a mistake they simply cannot make.

Jones was not back at Station 2 for five minutes before his battalion chief called. He knew his boss would be upset, but he was not prepared for his chief’s line of questioning: What was his role on this call? Did he not see the rhythm? Did he do anything to check the quality of the care provided?

Why was the battalion chief acting as if he were responsible for what happened? He did not provide patient care. He was the captain, the person in charge. Of course, he was a paramedic, but his crew was responsible for patient care, not he. He was there for scene management, not patient care. Jones was perplexed by what his boss had asked him. Could he have done something to prevent this mistake?

Officer’s Role on EMS Calls Needs to Be Better Defined

Most fire-based emergency medical services (EMS) do a very poor job of defining the officer’s role on EMS calls. We do an excellent job outlining what we expect from our officers on fire or rescue calls. Most of us have several department procedures on what we expect of our officers on these types of calls, but when it comes to medical calls, we provide minimum guidance or training. What makes this so alarming is that EMS accounts for a large majority of the call volume for most fire departments. We must do a better job preparing our officers to manage EMS calls.

Scene Management

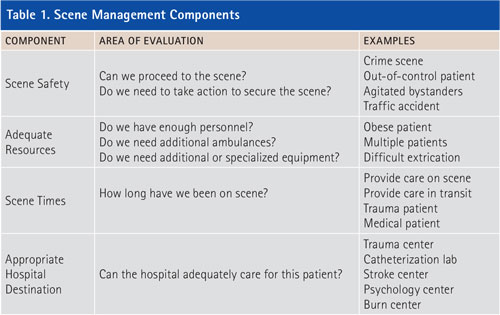

An officer’s role on EMS calls can be broken down into two components: scene management and patient care quality checks. Scene management comes fairly easy to most officers. These components are the big picture items we all learn in paramedic school. Table 1 shows a breakdown of the components of scene management. We can evaluate each component by answering a few simple questions.

A majority of the time, we can adequately address scene safety with dispatch information. If you are dispatched to an assault or a gunshot wound, you will need to have the police secure the scene before you make entry. On car wrecks, you will need to secure and control the traffic before you proceed. There are situations when a scene may become unsafe during patient care, such as when a distraught family member shows up and starts interfering with patient care. The officer must continuously evaluate the scene for safety and seek assistance from the police or take actions to create a safe work area.

The components of scene management do not require much time to adequately evaluate. Within a few minutes on scene or perhaps even with dispatch information alone, we know if we need additional resources. Is the patient morbidly obese? Will you need assistance lifting and moving the patient? Is the patient on the third floor of an apartment complex and you will need a specialized piece of equipment to help extricate the patient down the stairs?

Scene times and hospital destinations are dictated by the patient’s condition. For scene times, patients generally fall into two categories: stay and play or load and go. The officer needs to realize if patient care can occur on scene or if time is of the essence. Certain conditions require immediate transport; other times, a more thorough assessment can occur on scene before transport. As for determining the appropriate hospital destination, it is the officer’s responsibility to decide if the hospital chosen can adequately care for the patient.

The components of scene management can be completed quickly, but they must be evaluated constantly throughout the call. Scene management on EMS calls is common practice for most officers. The same cannot be said for the second component of officers’ responsibility on EMS calls: patient care quality checks.

Patient Care

When it comes to patient care, officers often take one of two approaches. Typically, EMS officers either outsource all aspects of patient care to their medical personnel on scene or try to control every detail of patient care. Officers who outsource all aspects of patient care are minimally involved in that patient’s care. They do not ensure adequate care is being provided. They will often remove themselves from the scene by retrieving the stretcher or fetching supplies. Officers who try to control every detail of patient care are so involved with the patient they lose the ability to evaluate the quality of care being provided and may lose control of scene management. Both approaches fail to ensure quality patient care is being provided.

Quality Checks

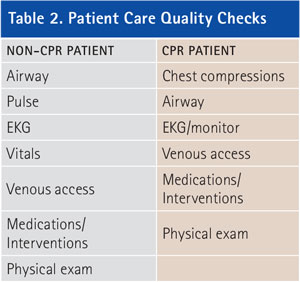

By evaluating quality checks, officers can ensure their personnel are providing the level of patient care their department and community expect. The patient care criteria for quality checks are based on two types of patients, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) patients and non-CPR patients. Table 2 shows a list of the quality checks for both types of patients. By evaluating each quality check and confirming it is adequately addressed, the officers can ensure a high level of patient care is being provided. It is important to understand that officers do not have to complete or be involved in each task, but they must ensure the skill or intervention being provided meets the needs of the patient.

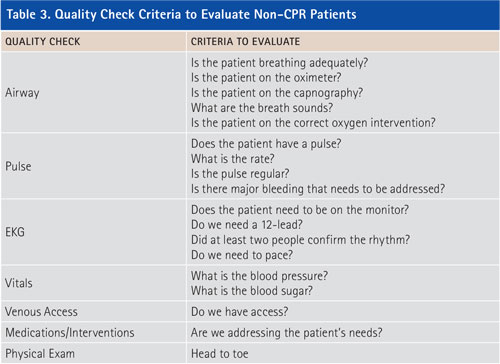

Non-CPR Patients

Table 3 shows the criteria for evaluating each quality check for non-CPR patients. The quality checks are listed in order of priority, but the order may vary depending on the needs of the patient. For example, if the patient is a 22-year-old female complaining of abdominal pain, we would focus less on the airway and more on other quality checks. The physical exam for this patient will have a higher priority than the airway. This does not mean that the airway can be ignored. The officer needs to ensure the oximeter and capnography are placed on the patient and then decide if an airway intervention is warranted.

Quality checks need to be based on the patient’s condition. It will not be necessary to go through every quality check on all patients, but understanding what criteria to evaluate against patient care priorities allows the officer to have more control over patient care. Using this method gives officers more assurance that the care they are providing meets or exceeds the quality expected by the department and the community.

Imagine you are the company officer on a crew transporting a patient your crew believes is having a stroke. You have notified the hospital. The hospital activates its stroke team, which is at the emergency room when you arrive. You hurriedly transport the patient in the room only to realize your crew never checked the blood sugar. The patient was not having a stroke but a diabetic emergency. The patient had low blood sugar, a condition that can easily be treated in the field. By using the quality check method, this mistake would not happen. You, as the officer, would have evaluated this quality check against priorities established by the patient’s condition.

CPR Patients

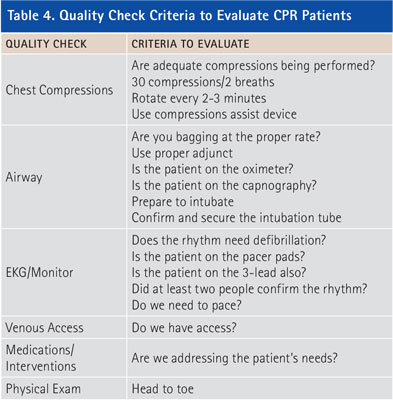

The quality checks for CPR patients vary to some degree, but the same concept of evaluating the quality checks against the needs of the patient applies. Table 4 shows the criteria for evaluating CPR patients. The officer must ensure quality chest compressions are being provided and a plan exists to rotate the individual doing compressions every two to three minutes. The airway often gets overlooked in a CPR situation. We get tunnel vision on starting compressions and determining the rhythm, and we forget to bag the patient. It happens more than we would like to admit. The officers must ensure someone is bagging the patient at the proper rate and preparing the intubation equipment.

Once the rhythm is identified, we can decide the proper intervention. If we defibrillate the patient, the officer needs to verify that it is at the proper joules and sequence. The officer must keep in mind that the defibrillation must be timed with the intubation procedure. We do not want to stop the intubation attempt in the middle of the procedure to defibrillate, or we will have to restart the intubation procedure from the beginning. At the same time, we do not want a major delay in defibrillation while completing the intubation process. The officer can time these two events by controlling the quality checks.

For example, you, as the officer, tell Paramedic A to bag the patient and assemble the intubation equipment with the assistance of Paramedic B. You instruct them to start the intubation procedure after Paramedic C defibrillates the patient. If the patient’s rhythm does not convert, the patient will be defibrillated again in two minutes. This gives the paramedics two minutes to complete the intubation procedure. Coordinating the quality checks allows the officer to control the scene without being directly involved in either task.

Going back to our first scenario, if Captain Jones had used the quality check method to control patient care, the mistake would have been avoided. The problem is Captain Jones was unsure of his role on EMS calls. Like most company officers, he has a strong understanding of his responsibilities on the fireground but a great deal of uncertainty exists on EMS calls. Officers are responsible for both scene management and the quality of patient care provided. Although officers should not be directly involved with patient care at the task level, they are still responsible for the overall care provided. The quality check method gives officers a simple method to compare the quality of patient care being provided against the needs of the patient.

CASEY McCASLIN, a 14-year veteran of the fire service, is a battalion chief with the Allen (TX) Fire Department. He has a master of public affairs degree and a B.S. degree in biology. He is an Executive Fire Officer alumna; a licensed paramedic; a rope rescue, confined space, and trench tech; and a former EMT and paramedic instructor at Collin College.

Engine Company EMS : EMS Point Person

Fire Engineering Archives