By Derek Rosenfeld

Now that the 2012 NFL season is entering its third week amid the decrying of replacement referees and moronic, divisive “tweets” from player agents, the subject of the ferocity of the sport was once again on notice, as approximately 120 players were carted off the field with injuries during Week 2.

Over the past five years, dire news on the brain health of football’s former greats and the recently retired have slowly trickled into the national consciousness, so much so that there are now debates on whether or not the sport should actually be played at all. The decline and deaths of all-time greats such as John Mackey, Mike Webster and, most recently, Junior Seau and the current conditions of more than 15 former players stricken with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) (Lou Gehrig’s Disease) or ALS-like symptoms, possibly as a result of the bodily damage inflicted by the game, are now at the forefront of a new perception of America’s most popular sport.

Now, with concussion lawsuits against the league piling up at an alarming rate (140 covering more than 3,300 former players at the time of this article), including one filed in May by 15 former players headed by Hall-of-Fame Running Back Eric Dickerson1 and another on September 19 in Mississippi by more than 50 other players who claim the league hid the dangers associated with head trauma, the focus on how the game should be viewed going forward is being considered. In fact, at least two new Web sites have been created to deal specifically with lawsuits stemming from past NFL play: www.nflconcussionslawsuit.com and http://nflheadinjurylawsuits.com.

American football has its roots in both rugby and soccer (which is actually called “football” in nearly every other country worldwide). It’s very reasonable to think that Walter Camp, considered the “Father of Football” and who created many of the rules and formation changes that we now immediately recognize on every Fall Sunday, never envisioned a 6’4”, 235-pound human wrecking ball sporting three-percent body fat and who runs a 4.4 40-yard dash roaming behind the line of scrimmage, launching himself into ball carriers and quarterbacks alike headfirst with reckless abandon. Nor did he envision things such as performance enhancing drugs or state-of-the-art helmets that give tacklers carte-blanche when they are going after an opposing player.

When comparing football to its closest relative—rugby—some scoff at the idea that the American game is more unsafe and conducive to injury. Rugby players are known to wear little to no bodily protection during games, save for a jockstrap and shin guards; this leads many to believe that more injuries result.

However, former Columbia University rugby player Wayne Mansylla disagreed when addressing the notion that rugby is a more hazardous sport than football. “Football is much more dangerous than rugby; the helmet is a weapon, plain and simple.”

THE EVOLUTION OF THE AMERICAN FOOTBALL HELMET

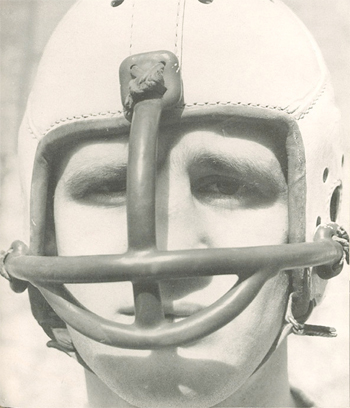

Unknown team, circa 1910

Left, future U.S. President Gerald Ford poses at his Michigan high school. Right, his University of Michigan football helmet, circa 1932-34.

A University of Nebraska football player, circa 1937

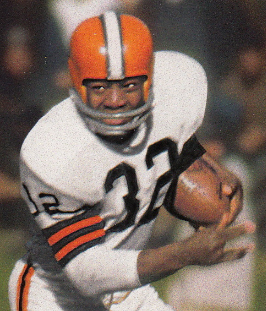

NFL great Jim Brown with the new two-bar facemask, 1958

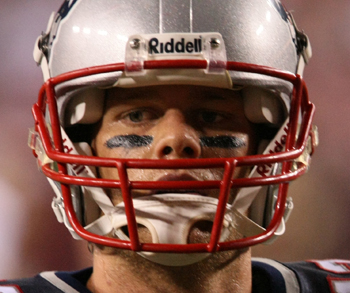

Hall-of-Famer Dan Fouts, 1975, and future Hall-of-Famer Tom Brady, 2009

So, is there a solution to this constant string of brain injuries and lawsuits plaguing the NFL beyond simply outlawing the sport? As with most things, change is inevitable, and this includes the way sports have been played over the past 40 years. Players have become bigger, faster, more athletic and, with salaries skyrocketing into the mega millions, products. With any successful product comes the need to invest in its protection. As a result, the league has done its best to create the best pads and headgear possible as well as add bars to what was once a single-bar facemask (and in the original days, no facemask at all). It has also changed drastically many of the rules regarding player contact at the line of scrimmage and to the quarterback, which has resulted in unprecedented offensive numbers. (There were three 5,000-yard passers in 2011, one more than the total number of 5,000-yard passing seasons in NFL history.)

With the increased protection allowing players to feel more invulnerable and free than ever before, and with the proliferation of media coverage through highlight reel-centric networks such as ESPN and the NFL Network, a whole new generation of athletes has become conscious of grabbing attention with the “big hit.” All around the country, at every level of the sport, players now look consistently to land a bone-crunching, crushing blow in hopes of wowing a crowd, awing teammates and opponents, or even making the 11 o’clock news’ “Top Plays.” Watch any level football game, and you will see players bouncing off each other as if watching a chaotic round of high-speed bumper cars at the amusement park. Punishing hits have drastically increased, leading to a corresponding decrease in quality tackling; this has contributed to a new era of career-threatening injuries and brain trauma, and it has trickled down to every level of the game.

This decrease in tackling has led not only to more damaging injuries but also to higher scores and an overall environment of inept defensive play.

I don’t believe there is an actual “solution” to the problem. The adulation, money, prestige, and joy that go with being a NFL player seem to trump the fear of leaving the game a physical wreck once the time comes to move on. In a survey taken of NFL players several years ago, an overwhelming majority of them answered that they would gladly forfeit the remaining 10 to 15 years of their lives to play the game that threatens their post-athletic life at every turn.

Perhaps one of the only ways to minimize these injuries would be to completely remove the facemask, returning to the days in which the game was played during its inception. Players would no longer be inclined to blast each other full force, many times leading with their head (or helmet, as it were). There would also be no facemask at which to grab, leading to a decline in potentially serious neck injuries; defensive players would have to aim lower on the body and be forced to use their arms to wrap up and bring down a ball carrier. Of course, this could bring about an increase in facial damage, but such is the nature of the game.

The sport can also adopt rugby’s general tackling rules, which require all defensive players to attack only at the ball carrier’s torso, never at the head or legs. Although this will probably never happen in American football, this rule has led to longer rugby careers and much less traumatic head injuries.

Until the sport of football relies less on the strength of the equipment and minor rule tweaks and adopts more stringent rule changes that disallow players to level each other, the medical carts will require more tune-ups, medical staff will be more on call, lawyers will continue to profit, and more athletes and their loved ones will carry the burden of the toll they took for playing the game they loved.

Special thanks to Peter Prochilo for help with this article.

ENDNOTES

- www.nfl.com/news/story/09000d5d8293ef46/article/eric-dickerson-files-concussion-lawsuit-against-nfl.

Photos found on Wikimedia Commons courtesy of, from top to bottom and left to right, Mytwocents, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum, Cbl62, Topps (2), and Keith Allison.

Derek Rosenfeld is an associate editor for Fire Engineering. He is an assistant baseball coach at Bloomfield (NJ) College, a NCAA D-II program that plays in the wood bat Central Atlantic Collegiate Conference. He has coached baseball at the collegiate level for eight seasons, including stints at New Jersey’s Bergen Community College and Ramapo College. He has also been an infielder in several highly competetive semipro baseball leagues throughout the New York tri-state area.

Derek Rosenfeld is an associate editor for Fire Engineering. He is an assistant baseball coach at Bloomfield (NJ) College, a NCAA D-II program that plays in the wood bat Central Atlantic Collegiate Conference. He has coached baseball at the collegiate level for eight seasons, including stints at New Jersey’s Bergen Community College and Ramapo College. He has also been an infielder in several highly competetive semipro baseball leagues throughout the New York tri-state area.

During the mid-90s, Rosenfeld was a three-year starter at second base for the Ramapo College baseball team in Mahwah, New Jersey, where he earned all-New Jersey Athletic Conference honors and was a two-time New Jersey Collegiate Baseball Association (NJCBA) all-star selection. He was named MVP of the 1997 NJCBA All-Star Game. He has a bachelor’s degree in communications from Ramapo College.