The Model Incident Command System Series: Dividing the Fireground

FEATURES

STRATEGY AND TACTICS

In nearly every emergency incident, there is more than just one problem to be overcome. A fire in the rear of a six-story apartment building may be extending unnoticed to Exposure 3. One side of the fire building may be in danger of collapsing on Exposure 2—the orphanage. Exposure 4, a dynamite factory, could pose a more serious problem than the fire itself.

How can the incident commander address all these concerns and still keep the fireground from becoming a hotbed of confusion? By dividing the incident scene.

In this twelfth article in the series on the National Fire Academy’s model incident command system, we will discuss the importance of dividing the incident scene and how without this technique, a loss of efficiency, increased confusion, excessive radio traffic, and an unacceptable span of control for the incident commander could result.

The incident scene is divided for two separate and distinct reasons:

- To establish geographic and identifiable locations;

- To assign functional responsibilities.

GEOGRAPHIC DIVISIONS

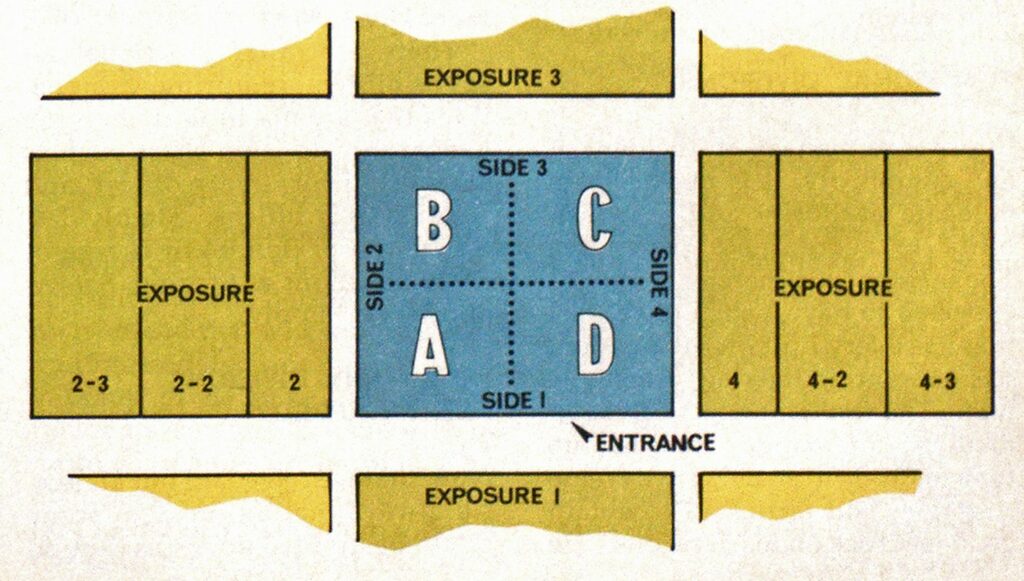

A relatively complete example of a geographic division system is shown in the diagram on this page.

However, this is not the only system that could be used; and it is imperative that all personnel and companies working together have a complete familiarity with the system chosen.

Regardless of which system is selected, once an individual is given a location with any alphanumeric designation, he should be able to determine not only where that location is, but the location of every other sector, side, or exposure in, near, and around the incident’s center.

The system shown in the diagram on this page numerically indicates sides of the fire structure and their related exposures. With the designated front of the structure called Side 1, the remaining three sides and their respective exposures follow in numerical order, 2,3, and 4, in a clockwise manner. Thus, Side 2 is the left side of our structure. The buildings, etc., exposed to that side are called Exposure 2 (2-2; 2-3; 2-n) as may be needed should conditions worsen. If the complexity of the fire building is such that the incident commander’s span of control is in danger of becoming ineffective, it too may be further divided and assigned to a staff officer. In this case, the interior is divided into four quadrants, each designated by a letter to differentiate interior from exterior locations. We may call our left front quadrant A and proceeding again clockwise, list the remaining three quadrants as B, C, and D.

The value of the geographic division system lies in the clarity with which we can rapidly designate areas of the fire building or any exposed building. When asking for reinforcements, an officer could very quickly tell the incident commander exactly where to send these personnel. When a status report on conditions in a building is given to the incident commander from a company officer, the incident commander’s perception of where the problems are would be greatly enhanced through the use of the geographic division system terminology. For example, “I have contained the fire in the rear of the building, but we still have fire in one of the partitions.” Where in the rear is the fire contained? What partition is the fire still in? The officer could have said, “The fire has been contained in Quadrant B, but we still have fire in the partition between Quadrants B and C.” There is no doubt where the fire has been contained and where the fire is still burning.

The value of this division system can be further seen in the following example: You are walking across the roof on your way from the front of the building to the far, right, rear corner. On your handi-talki you hear, “Captain Engine 2 to Command—I have roof collapse in my area.” You stop walking immediately. You want to run, but you don’t know where the roof collapse is. Where is his area? Are you standing on his area now?

This could all be avoided by the following radio report: “Captain Engine 2 to Command—I have roof collapse in Sector C.” You heard the transmission; you know where you are on the roof; you know what area you have to avoid. Your actions have been coordinated simply by the use of the geographic division system.

FUNCTIONAL DIVISIONS

In order to manage an incident of any complexity, it is necessary to delegate authority and responsibility to subordinate personnel. The incident commander cannot be expected to have a span of control that has every unit on the incident scene reporting (talking) directly to him. The resultant effect will be an incident commander who has no time to think, to analyze, to develop strategies and tactics, or to obtain good feedback on his decisions. He will simply be reacting continually to the communications made by others.

It is possible to delegate authority to anyone without using a functional division system. However, there will be less confusion and geographic areas of responsibility will be immediately recognized if a functional division system is used. The functional division system uses a similar division system diagram as the geographic division system. By using the same alphanumeric system, one system will lay very nicely over the other, thereby nearly eliminating our need to learn two distinctly different systems for command and control of the incident.

For example, when the incident commander delegates responsibility for the rear of the building to a junior officer, the junior officer assumes the radio designation of Division 3. Whenever the incident commander or any subordinate unit commander wishes to contact the person in charge of the rear of the structure, they simply call Division 3. Whoever is in charge of the rear at the time answers the call by saying “Division 3.”

In order to eliminate confusion on the interior of a structure, it is suggested that the person responsible for interior operations of the structure be designated as Division A. At multi-floor operations, simply use Division 2A for the second floor, Division 3A for the third floor, Division 10A for the tenth floor, etc. Additionally, the individual in charge of roof operations would be called Roof Division and the person in charge of basement operations would be called Basement Division.

There are other functional responsibilities requiring designations that are not indicated on the geographic division chart, such as staging officer, safety officer, and water supply officer. Simply designate the personnel in charge of these functions as Staging, Safety, and Water Supply.

HOW MANY DIVISIONS ARE REQUIRED?

Now that we have laid out all possible ways that an incident scene might be divided up, let us caution you against using every single one of these at every single incident. Only sector as much of an incident as you need to. Dividing an eight-slice pizza 64 ways may make for an interesting engineering study, but it makes for terrible control of the fireground.

Photo by Eric E. Emerson

The complexity of the incident as well as the number of companies and personnel responding will determine how many divisions are required.

Some departments, primarily those requiring some mechanism to ensure that manpower is not wasted, often ignore the necessity to divide the incident scene into manageable parts. It is their belief that they have so few personnel that they cannot afford the luxury of supervision. However, in a department with inadequate manning, the loss of two or three personnel to jobs that are not coordinated with the rest of the operation can be devastating; and when the efforts of companies and their personnel are not coordinated, delays and confusion envelop the incident scene. Placing responsibility on the shoulders of an individual, such as a commander of an incident division, tends to ensure that the job is accomplished.

The incident commander cannot directly supervise all operations being performed at the incident scene, nor is that his function. The incident commander is the strategist and overall coordinator, not a line supervisor. When the incident commander is relegated to direct supervision of all operations, there is little doubt that his department practices free enterprise firefighting. Personnel who complete an assignment (or leave it unfinished because they are not properly supervised) assign themselves to other jobs that may not be coordinated with the incident commander’s overall operational plan. This wastes effort and delays the controlling of the incident.

A basic incident

A simple, one-alarm assignment on a single-family dwelling may only require an incident commander and a division positioned in the interior. This division is in a place that the incident commander cannot see from the outside command position. A set of eyes, an analytical brain, responsibility, and coordination are required at this location. The division commander would handle the management and supervision of all personnel inside the structure.

All questions and information from interior personnel would be directed to the division commander, as would communications from the incident commander to interior personnel. As can readily be seen, even if there were three or four personnel with portable radios from different companies on the interior, only the division commander would talk to the incident commander and vice-versa. The amount of radio harassment being directed at the incident commander would be severely reduced. This would give the incident commander more time to recognize problems, analyze the options, and coordinate the effort being applied to control the incident.

The complex incident

It is important that each person supervise no more than five subordinates. Under emergency conditions, this is a reasonable number of persons reporting to someone who has to make immediate and rapid decisions. Too many personnel reporting to one person will cause an overload that will produce poor and hurried decisions.

Many of us have commanded incidents where there were 10 or more companies on location with almost every supervisor trying to talk to the incident commander at the same time. Not just once during the incident, but numerous times while the situation was escalating, everyone was trying to get his point of view across to the incident commander to ask a question, or receive an assignment.

Were you totally overwhelmed? Did you have time to think, even just a little, to sort things out and reach the best decision?

It does not have to be this way.

At large, complex incidents, additional division commanders will be required as additional companies and resources arrive at the scene. With the first-alarm units in place and operating, it is time to prepare for the arrival of the in-coming units from the additional alarms that have been called.

The incident commander might designate one of the first-alarm company officers as division commander to direct operations on the first-floor interior. The division commander will also advise you of the needs on the interior and be a pivot point where additional personnel will be told to report for interior assignments. Other division commanders will be assigned as needed (division commanders do not have to be officers).

Normally, it is necessary to designate a Division 3 (rear of the structure) since the incident commander cannot readily see the opposite side of the building from where the command post has been established. The job of Division 3 might be given to the officer/acting officer of the first company assigned to the rear of the building.

As more companies arrive at this worsening situation, the incident commander could need division commanders on the second floor (Division 2A), Roof Division, Staging, Water Supply, and Exposure 2 and/or 4. Since all of the operating companies would be assigned to the division commanders, it is most likely that the incident commander would only be conversing with the division commanders and some support staff at the command post. The span of control would be reasonable and manageable. The incident commander would have time to think and analyze before making decisions, especially if he has someone else manning the radio (see “Incident Command” in the March 1985 issue of FIRE ENGINEERING).

Continued on page 81

Continued from page 79

Who must recognize when one of the division commanders has too many personnel reporting to him? The division commander.

Should that be the case, he simply creates a subordinate division commander to himself who manages a portion of the work. This officer would report directly to the division commander.

Now, the incident has been reduced to manageable proportions through the delegation of responsibility and authority. No one is overloaded. A person is now checking on quality, quantity, and time of all work. The effort is being coordinated by the incident commander and his division commanders. The incident scene is not full of confusion; there is no free enterprise; and the radio channel(s) is relatively quiet since most conversation is now taking place faceto-face between division commanders and company officers.

USING FUNCTIONAL RADIO DESIGNATORS

Why not use radio designations that tell who the division commander is, such as portable Engine 11, Chief 12 portable, Unit 11 P, or Captain 23? Although these designations do a good job of telling us who we are talking to, they do an extremely poor job of telling us what function they are performing and where their location is.

In addition, what has to happen each time we change the person who is a division commander? For example, Captain 11 is in charge of the interior in the early stages of an escalating incident. All the companies who were sent to the interior were told to report to Captain 11. Any time anyone wanted to speak to the interior commander they used the radio designation Captain 11. About 30 minutes into the incident, the incident commander sends Battalion 2 inside to take over the interior command. Who are all the subordinate commanders calling on the radio? Captain 11! This will cause confusion until everyone is notified of the command change.

However, what if the interior commander used the function title division commander. The function title tells where the individual is located. This is much more important than who the individual is. Most of us can tell who it is by listening to the voice on the radio. When division commanders are changed, the title remains as the informational contact.

These are some finer points in the application of an incident command system that are designed to reduce confusion on incident scenes. When you are faced with a large, complex incident, everything that can be done to reduce confusion among the companies and commanders is critical to a successful outcome. If your incidents are confused and full of free enterprise firefighting, it is because you are choosing to do it that way. There is a better way—but it is up to you to implement it.