The Management of Change

FEATURES

MANAGEMENT

A game plan that’ll help you to move with the changing times.

One of the most stressful and difficult tasks that the modern fire service manager confronts is the management of change. This is true for both the new manager and for the more experienced manager, whether at the company level or at the level of chief executive officer, as change imposed by external and internal sources places strain—often considerable strain—on the department.

Let’s examine a model for the management of change. For the model to be successful, it’s first necessary to accept the premise that the fire service exists in a dynamic world of constant change. No assumption is made as to the value of change. Change may be good, bad, or have no effect.

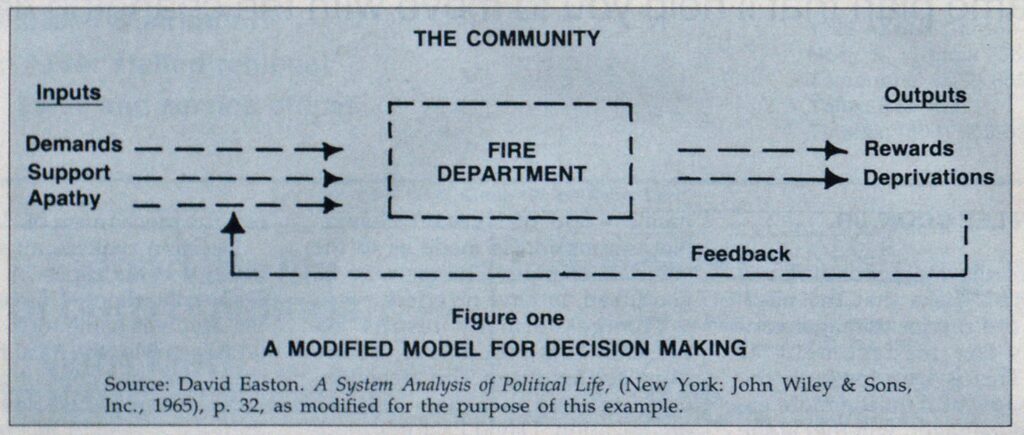

Change normally results because of, or is a product of, a stimulus acting upon the decisionmaking apparatus of an organization. David Easton’s modified decision-making model in Figure One (see page 114) illustrates such a mechanism.

Figure One illustrates a number of areas of input received by the department in general and the chief decision maker in particular. Such inputs include demands, support, and apathy. Examples of demand might include the request by a newly annexed area for increased service levels, or requests by employee groups for higher wages or improved working conditions. Support might take the form of increased funding by the policymaking body or a donation by the local civic club for a new piece of equipment. Apathy is also an input. People who aren’t concerned with the level of fire protection in their community, for instance, affect the mechanism of change.

Decision makers must consider these various types of input and respond to them. This response often involves some form of change. (For example, the local fire department assumes control of the EMS because the public demands that there be a system in place to provide quality prehospital emergency care and there is no other provider.)

Demands or inputs are transformed by decision makers into plans, programs, and policies. These responses or proposed solutions take the form of outputs. Outputs will often result in a particular group being rewarded. For example, the union demands a pay raise and receives one. However, the group making the demand does not always receive exactly what it’s demanding (output does not always agree with the input). The union may w’ant a five-percent raise and the city council may only grant a two-percent raise. This outcome could well be described as a deprivation. Dissatisfaction may then be fed back as an input in the form of apathy or additional demands.

It should be remembered that change is stressful to firefighters and to the organizational structure as a whole. Change often is desta-. bilizing. Therefore, the ability of an organization to translate demands into change is a direct function of the organization’s capacity to respond to change and the types and scope of the demands which drive the change.

A number of the factors which limit or enhance an organization’s capacity to assimilate change are:

- financial resources;

- community involvement and citizen support;

- support of policy makers (mayor, council, district board);

- support of employee or membership groups or associations (informal groups, fraternal organizations, unions);

- support by selected interest groups (from civic, political, and departmental areas);

- flexibility/ability of the organizational structure to facilitate change;

- available tools and technology;

- “stars” (those persons within the organization who have the vision and ability to create concepts and follow through with the implementation of these concepts);

- apathy (on the part of leadership, members, and public).

The above list is certainly not allinclusive, but rather illustrates that the mechanism of change can be a complicated issue, and that influences of management decisions bear down from many angles. The greater the number of these factors present, the greater the organization’s capacity for change.

One should not infer from this discussion that all the factors listed are weighted equally or that it’s truly possible to qualify the factors. Different factors will tend to have a different weight as the issues change. For example, factors 2-9 could all be present, but if there are insufficient funds available for a given project, it may be impossible for a given change to occur.

While an organization may have the capacity to change, change won’t happen unless there are sufficient reasons or demands for it to happen. The following list exemplifies the types of demands which often stimulate change:

- the desire of the CEO or executive staff for a change;

- the desire of key policy makers for changes to occur;

- demands imposed by the citizens served by the department;

- demands imposed by various interest groups (for example, a neighborhood association);

- changes in the economy which impact funding;

- change imposed by outside regulatory bodies such as the federal government, state government, etc.;

- communitv dynamicsgrowth, retrenchment, and other demographic changes;

- catastrophic events —large, man-made or natural disasters which overpower the depart-

- ment’s ability to deliver services, such as chemical spills that necessitate large-scale evacuations, or uncontrollable wildfires;

- apathy.

Again, the above list is not meant to be all-inclusive, but rather identifies the types of demands which might be placed upon an organization by both internal and external forces. The more types of demands placed upon the organization, the more pressure there is to respond to those demands and make the required changes which satisfy the imposed needs.

It must not be assumed that these demands are either positive or negative, nor can it be assumed that each type of demand is quantifiable. Furthermore, it can’t be assumed that each type of demand is of equal value or weight. Depending upon the issue, any one of the items from the ‘demands’ list might equal or exceed the sum total of the other eight.

If the demands for change exceed the capacity for the organization to change, the stability of the organization might be affected.

Figure Two presents a model for the ordering of change within a typical fire service organization.

The goal of anyone managing the process of change should be to achieve as much of the desired change with the least cost or discomfort. Least discomfort in this sense implies the minimization of resistance to change and with the least amount of damage to the organization’s stability. Figure Two graphs an area of tolerance which represents a balance between demands for change and the capacity for change.

For the sake of discussion, assume that a value of one is placed on each factor affecting both capacity to change and demand for change. It’s then possible to graphically plot outcomes for different scenarios in an attempt to predict if the amount of change imposed at any given time will be destabilizing or not. Three equations are possible:

C D = Oi C D = C = D = where C = Capacity for the organization to assimilate change;

D = Demand for change imposed on the organization; and = Outcomes.

According to the change model and the above equations, at least three outcomes are possible. In outcome Oi, in which C D, the demand for change exceeds the capacity of the organization to respond to change. This scenario can lead to instability and, ultimately, to a repressive organization if those demanding the changes tend to be autocratic and fail to bring the people within the organization to a point where they can understand and adapt to the required changes.

Outcome in which C D, reflects an organization that’s ripe for change but lacks either the leadership or necessary incentives to bring about change. This situation often results in stagnation and/or decay of the organization. This also tends to be destabilizing. If we again assume that the communities in which fire departments operate are dynamic, everchanging communities, one can make the subjective inference that if the department fails to change and grow with the community, stagnation will result.

Finally, outcome O3, in which C = D, graphs the ideal change model when the organization’s capacity for change is developed in direct relation to the demand for change. This is the least painful and the most productive outcome and should be the goal of the skilled manager. Note also that in Figure Two at last three distinct levels of capacity vs. demand are identified: low capacity/low demand, medium (or moderate) capacity/medium demand, and high capacity/high demand. As transition and growth occur, these levels may be thought of as levels of organizational maturity.

Maturity is not indicative of the age of the organization, but rather the state of organizational development: its capacity to assimilate demands and process those demands into an acceptable response (change) in the least destabilizing manner. Ideally, the skillful manager will help facilitate the maturation of an organization. It must be emphasized, however, that the level of maturation is not static; nor does it always move from low to high. Many factors exist which can transform even a highly mature organization (A 9/9 on the graph in Figure Two) into a organization with a medium-to-low capacity for change.

Take, for example, the case in which a new fire chief is appointed. The new chief is well-accepted by the city council, the community, and the firefighters. The chief implements many popular changes and receives adequate financial support. However, after a few years, the local economy experiences a lengthy recession which eliminates much of the necessary financial support for the department. This results in increased dissatisfaction among the firefighters, and the fire chief is replaced by a person who’s opposed to any type of change whatsoever. Therefore, the organization is transformed from one with a high capacity for change to one with a low capacity for change and becomes stagnant. This example is extreme, but it’s illustrative of the continuum in which the process of organizational change exists.

Figure Two diagrams an area of tolerance in which it’s possible that C D and the stability of the organization won’t be adversely affected. The area of tolerance will be defined by both the issue confronting the organization and its overall health and stability. In organizations having a low capacity for change it might be expected that where C D or C D, the difference would not exceed a value of approximately one. An organization with a relatively high capacity for change might be able to tolerate even greater difference between C and D, depending upon the issue.

Obviously, the proposed change model is an oversimplification of the dynamics of the change process. Capacity for change and the demand for change will seldom fit into equal values of one and allow the manager to graph the process as neatly as illustrated in Figure Two.

However, the model is useful if the manager will go through the exercise of weighing the demand for the change against the ability for change to occur. Before a change can occur, it may be necessary for the manager to attempt to further develop the organization’s capacity for change. This can be a slow and oftentimes frustrating process. It’s especially true if there are inadequate resources available or if members or groups are particularly resistant to change.

The manager must be able to predict the amount of instability that will be created and assess if the change is worth the costs created by the process. In some instances it will be necessary to determine if the manager or the organization can surv ive in the ensuing instability. This is especially true in highly politicized environments.

Another thing to keep in mind is that change is seldom greeted with open arms and shouts of joy. People tend to become complacent and set in their ways and resist any change. Many people will think that things are going fine and that since it’s not broken (in their minds), why fix it? The value of change is usually in the mind of the person desiring the change.

If the manager accepts the fact that there will be resentment, then the manager should begin to assess the amount of resistance present and seek ways to neutralize that resentment. Karl Von Clausewitz’s observation is appropriate in this regard. He stated, “If we want to overpower our opponent, we must proportion our effort to his power or resistance. This power is expressed as a product of two inseparable factors: the extent of the means at his disposal and the strength of his will.”1

Change is threatening to individuals and organizations alike. A proposal to change a method of operation can easily escalate into an emotional issue, particularly if the procedure being changed is someone’s sacred cow. Firefighters have a highly active formal and informal communications network in both social and professional situations. Rumor encourages skepticism; skepticism can breed paranoia; paranoia in turn substantiates rumor. The story which results around the campfire will often bear little resemblance to the facts. Facts seldom confuse the issue. Besides, it’s more fun to speculate than it is to know the truth. The truth usually isn’t nearly as much fun.

Knowing all of this, the perceptive manager will keep his finger on the pulse of the organization and will only proceed with changes as is advisable. In the early 16th century, Niccolo Machiavelli offered some interesting advice in this regard in his work, The Prince. Machiavelli said that circumstances dictate the speed at which change can occur, and he marked the importance that fortune plays in human affairs. The effective manager knows when to make changes . . .and when not to.

Often, change can occur at a rapid pace without any major problems. At other times, change can be tolerated only at the proverbial snail’s pace. Time and circumstances deal all the cards. What has worked in the past may not work in the future. At each juncture, the manager must plot the coordinates on the change model and attempt to predict the outcomes and assess the chances for success or failure. Failure will occur, sometimes. The successful manager must be willing to risk failure and be able to recover from the failure. The good manager is one that simply makes more right decisions than wrong ones. Fear of failure often prevents managers from making any decision at all. More often than not, no decision is a decision in itself that will have impact upon the stability of the organization.

Just as the incident commander must be ready to make an immediate size-up and take action in an emergency, the manager must be able to size up the organization and respond to its needs by selecting the tools, theories, and principles which will best apply in any given situation. Hopefully, the choices will be the correct ones and the outcomes will be the most desirable for the organization. The proposed change model discussed in this article should serve as one of the tools that will enable the manager to contemplate a change and facilitate its implementation.

‘Karl Von Clausevvitz. On War, trans. O.J. Matthijs Jolles, (New York: The Modern Library, 1943), pp. 5-6.

The fire service is a very traditionbound organization. Because of this, many departments resist change. Unfortunately, needed change sometimes must be forced upon the department from the outside. It’s much more desirable to manage change that it is to have change manage us. It should be remembered that the fire service is just that, a service provider. Our citizens are our customers and we must be responsive to their changing needs. The public suffers if we fail to respond to changing times.

We have occasionally been guilty of believing that we can’t be replaced. True, we have a monopoly. But because of this, we should work even harder to be sensitive to our customers. We can be replaced. Privatization of public sector services is becoming increasingly commonplace. If we continue to operate in a vacuum, we might well report for duty some morning only to find a “Going Out Of Business Sale” sign in our front window. As Pogo, the comic strip character, said, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

We must avoid the seven steps of stagnation. These are the all-toocommon responses to any proposed change. They are:

- “We’ve never done it that way before.”

- “We’re not ready for that.”

- “We’re doing all right without it.”

- “We tried that once before.”

- “It costs too much.”

- “That’s not our responsibility.”

- “It just won’t work.”

Change is not always for the better and sometimes it doesn’t work, but we owe it to ourselves and the public to at least be open and receptive to change. We must work to find the best way to accomplish any and all tasks. As it was popular to say in the 1960s, “If you’re not part of the solution, then you’re part of the problem.” The decision is yours to make. Whether we like it or not, we’re all factors in the management of change.