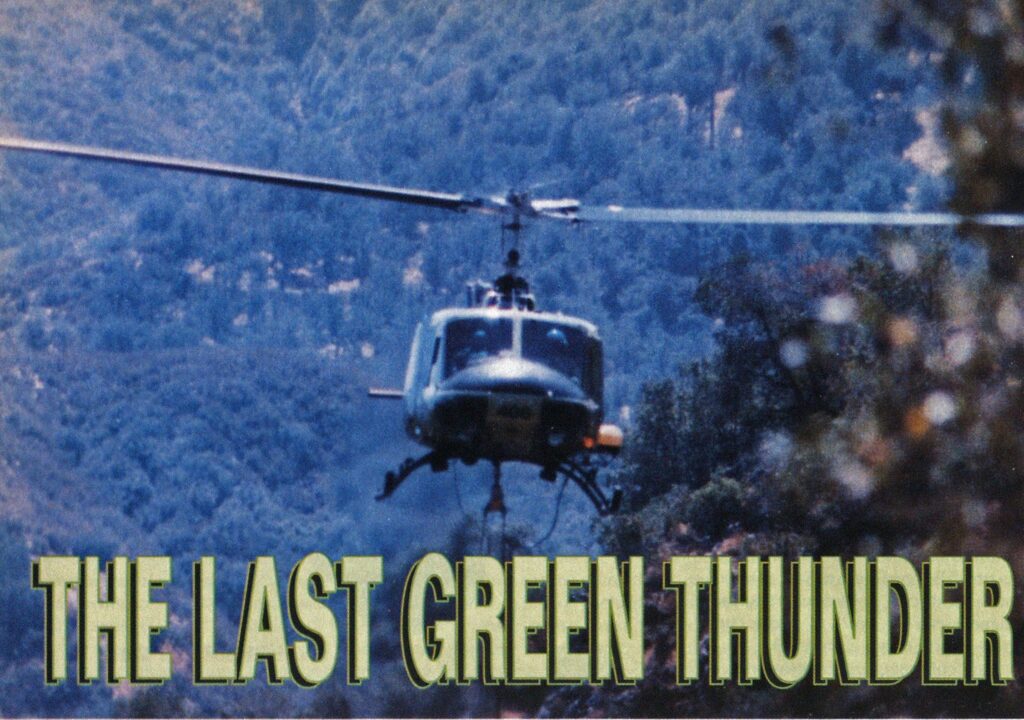

THE LAST GREEN THUNDER

(Photos by Norm Booth, Jimmy Wilkins, Daryl Mansheim, and Brian Sullivan.)

The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CDF), the second largest fire department in the western world (Australia’s Country Fire Authority is the largest), has long recognized the need for and value of tactical operational aircraft, which now are a valuable component of its complex. We have 19,000 paid and volunteer firefighters, 577 fire stations, and 72 fire lookouts. Each year we respond to more than 20,000 wildfires and 150,000 other emergencies and protect more than 41 million acres of California’s watershed and millions of citizens. In addition, the CDF routinely responds, with agencies in 40 of the state’s 58 counties, to provide fire protection services.

The CDF fleet includes 51 aircraft, including the only twin turboprop firefighting air tanker in the world. Each of the fleet’s 19 S-2 air tankers carries 800 gallons of fire retardant. The retardant is a suspension of water, a coloring agent (for quick visibility), guar gum (as a thickener), and salts that maintain moisture on the vegetation; the suspension ultimately breaks down into a beneficial fertilizer. The two SP-2H air tankers each carry 2,000 gallons of firefighting retardant. Thirteen air-attack observation planes, 11 helicopters, and five executive aircraft complete the fleet.

The first helicopters incorporated into CDF service, during the late 1950s, were primarily three-seater Bell or Hiller models provided under contract with the private sector. Six full-service contract helicopters (four-seater Bell 206A and FH1100) were acquired in 1972.

To establish a state owned and operated system that provided increased weight-carrying capacity, the department acquired in 1981 a fleet of UH-1F helicopters. The UH-1F, called “green thunder” because of its lime-green color, was designed by the United States Air Force and was created to use up its stockpiles of General Electric T58-GE-3 engines. Many of these aircraft found their way into firefighting agency inventories. Seven of them were refurbished and strategically placed around California at Beiber, Kneeland, Vina, Howard Forest, Alma, Columbia, and Hemet. Two spares function as maintenance “floats.” Another, still a private-contract ship, is at Boggs Mountain. The last of the UH-1F “green thunders,” Copter 406, was refurbished and is stationed at the newly established Bitterwater Helitack Base 20 miles east of King City, California. Manufactured in 1965, Copter 406 had been used by the Air Force until 1975, when it was retired and stored at the Davis Motham Air Force in Arizona until it was sold to the fire service.

The CDF maintains an extensive list of private contractor “call-whenneeded” helicopters for use on large fires, a policy that helps to support the local economy.

CREW FUNCTIONS

The typical CDF Helitack crew consists of a pilot, two captains, an engineer, and up to eight firefighters. The pilot’s responsibilities include coordinating the distances among the other aircraft participating in the incident, acquiring and selecting targets, controlling water drops, “medivacing” the injured, and transporting personnel and equipment.

The first captain assists in operating the three multichannel on-board radios, acts as the air attack coordinator for the air tankers and other helicopters (until the air attack officer arrives on scene), helps to spot flight hazards, performs mapping and recon duties, and assists the ground crews with tactical observations.

The second captain and the firefighters—the Helitack crew—ride in the helicopter’s internal payload area. They use chain saws and other hand tools to construct a line in front of the fire or along its edge by removing the vegetation down to mineral soil. The second captain, the crew’s leader and supervisor, selects the hand tools to be used, determines the safest access to the fire’s perimeter, and chooses the fire control tactics and strategy.

Each firefighter has specific duties:

- Two firefighters assigned “bucket A” and “bucket B” hook up or take down and store the 325-gallon “Bambi” bucket used by the helicopter for foam-injected water drops.

- Two firefighters designated “tool A” and “tool B” remove, sharpen, and return to their storage location (in the helicopter’s tail) the tools used in the operation.

- One crew member is responsible for packing two portable radios—in addition to the two carried by the captain—and the spare batteries, for maintaining communications with the captain in the event that the crew becomes tactically divided, and for assisting with communications with other fire suppression forces.

- The pilot’s assistant (P.A.) prepares load calculations, assists the pilot with minor aircraft repairs, and briefs non-Helitack personnel on helicopter procedures.

The duties of the firefighters and captain are rotated regularly to maintain uniform competency levels. Crew members pack 25 pounds of gear in addition to their tools. The gear includes a fire shelter (in case the fire overruns the crew), canteens, fusees (flares for burning vegetation), knives, flashlights, compasses, and other equipment.

The Helitack engineer brings to the scene the Helitender (a helicopterservicing vehicle that contains 1,500 gallons of Jet A fuel, cargo nets, aerialignition equipment for burning vegetation, extra hand tools and foam, and other equipment needed for extended helibase and helicopter operations.

Pilots and captains enforce the rules and ensure that the weight and balance restrictions are not breached, l-oad limitations are governed by the density altitude measurements. Hot air and air at higher elevations, because they are thinner, reduce the size of the load a helicopter can lift. Load calculations are done at different temperatures and altitudes on a daily basis to determine the maximum load capacity for a particular day.

Successful Helitack operations depend on the strategic deployment and the early arrival of the Helitack crews on the scene—during the initial-attack phase of a “going fire.” By supporting the air tanker’s applications of retardant and the helicopters’ drops of water with quick, aggressive ground actions, the Helitack crews have been extremely effective in suppressing wildland fires.

The air-mobility concept of the helitack is especially suited for the concerted air and ground action required to control the early phases of a fire, to cool down hot spots along the fire’s perimeter, and to contain spot fires burning outside the perimeter of the primary fire. Helitack crews usually are kept within their initial-attack areas and often do not get to major fires because of their unique value in combating the initial fires and keeping them small.

In a typical dispatch, the helicopter approaches and operates in the fire area at or below 500 feet above ground level. This brings the ship in below the air tankers and the airattack officer flying high “cover” in a Cessna 02 observation plane. Upon arrival at a fire, the crew locates a safe “LZ” or landing zone where the Helitack crew disembarks, connects the Bambi bucket, and retrieves the designated tools. From this point, the Helitack crew proceeds to some designated point on the fire line and begins to construct a handline.

Meanwhile, the helicopter locates a water source, dips, fills the bucket while hovering, and returns to support the Helitack crew with water drops. During this process, the fire often is too hot and/or too dangerous to enter, and the Helitack crew must wait in the brush for the first drop to punch a hole in the fire. These tandem efforts continue until other forces arrive on scene, allowing the two halves the option of working independently.

ADVANTAGES AND LIMITATIONS

Among the advantages provided by helicopters is their ability to access areas denied to fixed-wing aircraft and ground vehicles, thus allowing the crew to enter remote, rugged, or isolated areas. This sometimes means that the crew must be unloaded at locations where only one skid can contact the ground. The ship sometimes cannot land at all, and the crew must “helistep” off (carefully balance their weight while climbing out the door onto a skid and down into the brush as the helicopter hovers overhead). The vegetation often is so thick that the crew is forced to crawl underneath it to reach the fire.

Helicopters have some limitations as well. When down in between the trees, for example, the distance needed to clear the rotar must be accurately gauged. With a fixed-wing aircraft, on the other hand, it is necessary only to look out the window and judge the distance to an object. Other hazards include poor visibility due to the fire smoke; “greyouts” or “brownouts” from flying ash or dust; midair collisions; pilot fatigue; and the ever present danger of striking power, phone, or other lines. In addition, air tankers drop their loads—ranging from 2,600 to 3,000 gallons of fire retardant and weighing more than nine pounds a gallon—at 150 miles per hour, 75 feet over the ground crew’s heads, while uprooting trees, brush, and grass in the process.

Despite these hazards, the CDF has experienced only one helicopter accident (no fatalities), even though its helicopter fleet is available 96 percent (maintenance average) of the year and has logged more than 18,000 flight hours over the past nine years.

OTHER FUNCTIONS

The CDF aircraft respond to other emergencies as well. Two of its helicopters participated in rescue and evacuation operations during the October 1989 Lorna Prieta earthquake. In addition, our helicopters have responded to floods, levee breaks, medical emergencies, vehicle accidents, aircraft crashes, and search and rescues.

When not engaged in emergency responses, our helicopters and crew are involved in activities such as air shows and static displays for the general public, lightning detection (hunting down strikes after storms), administration and reconnaissance flights, and sling-loading supplies into remote lookouts and other locations.

Maintenance and training flights also are part of the CDF schedule. Every pilot must apply for recertification in in-flight emergencies and landing procedures each year. The test involves experiencing the loss of various controls, running landings (similar to an airplane’s landing without wheels), and autorotational landings. Because the two pilots receive only one opportunity a year to perform these maneuvers under controlled conditions, Helitack officers accompany them so that they can observe and understand these maneuvers should they ever have to experience them or perform them in emergency situations.

Since 1980 when the California State Legislature approved an incentive program that permits landowners to use fire to control unwanted vegetation, the CDF has participated in the program’s implementation. Controlled burns are used to keep hunting areas open, to attract game, to improve grazing capabilities, to clear brush and dead vegetation, and to increase water runoff in much the same manner as the indigenous Indians of the past have done. More important, the program helps to reduce wildland fire suppression costs by removing extreme fire hazards under controlled conditions.

The fires arc set in a prescribed manner and under specific environmental conditions that permit the burn to proceed safely and under control. The CDF assists local landowners by developing a management plan, placing control lines, and strategically staging equipment around the proposed fire’s perimeter. The area then is set afire, usually with the helitorch or the terra torch, which ejects napalm from the air or ground, respectively.

FLEET CHANGES UNDERWAY

The CDF recently acquired 17 newer model EH-IF! and six EH-IX Bell helicopters through the Federal Excess Program. Twelve of the helicopters will be remodeled to conform to the standard UH-1H configuration over the next several years. Modifications will include installation of the tractor-type tail rotor, state-of-the-art avionics and radios, and the “super 205” (1,800 shaft horsepower) engine. One of the newer Model H helicopters sporting the new whiteand-red color scheme that the FAA has determined is more visible against the ground and sky already is in service at the Vina Helitack Base in Butte County, California.

While we welcome the stronger, more versatile, newer models, the CDF crews bid farewell to the old “green thunders” with a touch of melancholy. We doubt, however, that the days of the “green thunder” aiding humanity are over.