By Rommie Duckworth

Every day in your response area, large vehicles filled with potential patients and often carrying hazardous materials may be headed for a collision with another vehicle, a solid structure, or a crowd of pedestrians.1,2

These mass casualties on wheels present a host of problems for emergency responders. Bus collisions may be inherently complex, but when you group and prioritize the issues, you can manage them quickly and confidently.3

Even relatively minor bus collisions present a variety of scene management issues that include in addition to the top priority of patient care the following: traffic flow, secondary collisions, extrication, rescue, hazardous materials releases, cargo security, interagency communication, and media and bystander management.4 Regardless of how many of these areas are your responsibility, to successfully manage a bus collision, divide the larger incident into smaller, manageable chunks. Don’t get distracted by the first or worst assignment. Defining your patients, problems, and partners will clarify your immediate incident priorities and help you move to accomplish them. Needs, resources, and conditions may vary, but the issues facing responders at a bus collision generally may be categorized as “lots of patients,” “lots of problems,” and “lots of partners.” This system makes it easier to delegate, coordinate, and act to resolve the incident.5-7

(1) Bus collision incidents have many moving parts, but the mindset of each part is simple: size up, set up, and move forward. (Photos by author.)

Issues Facing Responders

Numerous patients. Even if it is not your role to provide direct care, the first consideration at virtually all bus collisions is the large number of potential patients that must be managed. Whether patients number fewer than 10 or more than 100, effective use of a multiple casualty incident (MCI) system will streamline coordination of prioritized patient assessment and treatment and continue the forward movement of patients. (3, 4) Once you manage the patients, the remaining incident priorities are easier to resolve.

(2) Bus collisions may first be reported as routine motor vehicle collisions. Because of this, all responders, regardless of rank, must be prepared to arrive first and begin managing the incident.

Multiple problems. Bus collisions, especially those involving extrication, traffic control, and hazardous materials releases, can make it difficult to know where to begin. Take a moment to ask yourself on arrival, “What are my ‘problems’?” This analysis will enable you to break down, prioritize, and resolve the issues. In larger departments with more immediately available resources, problems may be delegated to incident branches, groups, or others. In departments with fewer immediately available resources, grouping problems helps you to see where immediate action is needed and what additional resources are necessary.

As with any other type of motor vehicle collision, you must operate under the incident management system and maintain awareness of the hazards present. Report critical issues up the chain of command, mitigate hazards where you can do so safely, and coordinate with other resources when the hazard is beyond your capability to address safely. (7)

Many partners. You will have to coordinate with other emergency and nonemergency agencies that often have competing priorities. (4, 6, 7) Anticipate these competing priorities, and know the resources your partners can provide before the incident begins. The best way to prepare for such emergencies is to train with these agencies before an incident occurs to develop the skills and build relationships that will help to ensure successful management of a bus collision of any size.

Managing a Bus Collision

As is true of all incidents, bus collisions are most efficiently managed by completing the right jobs in the right order. Start with standard operating procedures and predefined MCI roles. A simple system you can apply when tackling a task assigned to you is, “size up, set up, move forward.” Good coordination begins way before the incident occurs. This format can help you coordinate your resources for operational success before a bus collision occurs. (6, 7)

Size up. Begin your size-up by building a list of agencies that may be concerned with a bus collision incident along with their primary contact information. Include the operators of buses that travel through your response area, potential patient destination locations including hospitals, and sources of alternative methods to transport large numbers of injured and uninjured victims from the scene.

Set up. Once you have established a list of stakeholders, set up your response by reaching out to their designated contacts. Establish what their expectations and priorities will be when a bus collision occurs. Your system may not be ready to meet every expectation of every stakeholder, so consider meeting to set up short-term goals that may be achieved with current resources and long-term goals that will improve the system in the future. Where possible, establish written agreements and procedures to solidify the priorities and expectations agreed on by the stakeholders. These agreements do not constitute the plan, but they outline what everyone is trying to accomplish and willing to offer.

(3) Coordinating and communicating with partners are key to moving patients and resolving incident problems.

Move forward. Bring together as many representatives as possible to develop a bus collision plan that deploys resources to manage the incident and to attempt to meet stakeholders’ priority needs. Do not look on the plan as a rigid outline for operations at every bus collision incident but as a flexible framework that you will further hone with tabletop and full-scale exercises.

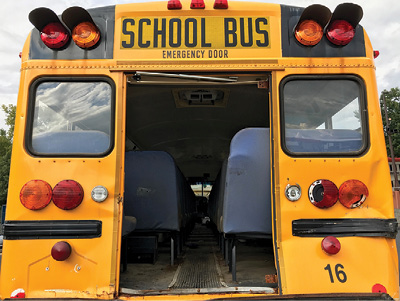

(4) Look for access and egress points in the right order: standard doors; then emergency exits like this one; and, as a last resort, extrication tools and techniques.

Arriving on Scene

Depending on how a bus collision is initially reported, responders may be dispatched for a large-scale incident or a routine motor vehicle collision. Because of this, all responders, regardless of rank, must be prepared to arrive first on scene and begin managing the incident.

Size up. Although not every responder may give a formal size-up report over the radio, every responder should do a personal size-up on arrival. A “size-up mindset” improves individual and group situational awareness.

(5) You don’t have to be a paramedic to help with mass-casualty care. Anyone can move priority patients forward with SALT methods.

Set up. Whether you are the incident commander or one of many responders, it is important that you establish or integrate with command on arrival. (6, 7) The temptation to “just do something” is appealing to many responders, but coordination and communication with partners are vital to the treatment and forward movement of patients and the resolution of incident problems.

Establish your incident area of operations, and set up clear paths of travel in and out of areas and vehicles. There likely will be a lot of responders, equipment, patients, and traffic on the move at this incident. Although you probably won’t have ideal conditions, the clearer you can make these paths, the faster everything can get to where it needs to be.

Move forward. From the moment you arrive on scene, your goal is to move the incident forward; usually, the best way to do this is to move the patients forward. If you are the first on scene, you are responsible for setting up the framework to make this happen by delegating the tasks of triage, treatment, and transport—in that order—to the available qualified crews. (3, 6) Although organizational resources and capabilities differ, initiating a mass-casualty framework helps to manage the scene.

Triage

Led by an assigned triage officer, triage allows responders to move patients forward in the most efficient way and to begin caring for them while doing it. In some departments, this may be a natural part of operations; in others, it may be delegated to emergency medical services (EMS) partners.

Size up. With few exceptions, the triage officer’s size-up should consider how to rapidly access the patients to triage them and get them to the patient collection point, treatment area, or area of refuge. (3) Questions to consider include the following: Is it best to protect them in place for now? Do you need to clear a path for them? If so, approximately how long will that take? What assistance will you need moving patients from the vehicles and hazard area?

Consider which of the three methods of vehicle access (or what combination) you have to your patients, and they have to you: (1) Standard—through the normal doors of the vehicles (the same way they got on/in); this is almost always the first choice of access and egress. (2) Emergency—through designated emergency exits such as windows and hatches; these exits are generally more restrictive than standard access. (3) Extrication—if neither standard nor emergency access is adequate, you will need to coordinate with rescue crews to perform extrication.8

Set up. As of the writing of this article, no triage system has proven superior; the best choice is usually the system with which your providers and partners are most familiar.9-14 (3) Use the steps “sort, assess, lifesaving interventions, treatment or transport (SALT)” to provide the framework field providers can use to bring order to chaos and help improve patient outcome. (3)

Move forward. SALT has two phases for triage. The first is an immediate or “global sorting,” which involves asking patients to walk to the patient collection point or area of refuge. Patients who can follow commands and walk are typically the least in need of resources. Next, ask patients to wave their arms to indicate that they need assistance. Patients who do so clearly cannot move (or they would have done so) but can still understand and follow commands. These patients will be assessed in a moment. First, however, EMS providers will assess the remaining patients. These are the patients who are unable to move or to follow commands or who have other obvious life threats. Regardless of whether your department is responsible for EMS, ensuring that triage begins quickly will help manage the incident in the immediate future as well as get patients moving forward to resolve the incident overall.

The individual assessment phase of triage of SALT involves no math or counting and allows patients to be provided with any lifesaving intervention that takes less than one minute, and the provider does not have to remain with the patient. Examples include rapid major hemorrhage control, airways opened (and two breaths for children), needle chest decompression, and so on. If the patients’ major bleeding is controlled after this intervention, they have a peripheral pulse, remain breathing on their own and are not in major respiratory distress, and make purposeful movements, they are marked green (minimal) if they have only minor injuries; they are marked yellow (delayed) if they are still seriously injured. If major bleeding is not controlled, they are not breathing on their own or are in major respiratory distress, they do not make purposeful movements, or they do not have a peripheral pulse—and if you believe that they are likely to live—mark them red (immediate). If you believe they are not likely to survive, tag them black.

Treat

Provide patient treatment in ways that will continue the forward movement of patients. Consider splitting the crews of incoming ambulances: Drivers remain with vehicles, and caregivers bring relevant gear and supplies directly to the treatment area. As the incident is demobilized, crews and equipment can be put back together. During the incident, priorities are often best achieved by moving the right resources to the right places as efficiently as possible.

Size up. The EMS provider in charge of patient treatment, typically designated as the treatment officer, must rapidly evaluate the resources. Think structures, staff, and supplies. (3, 6) First, consider available structures to protect the patients and allow providers to provide care and store equipment and supplies. Evaluate the staff that will be providing care and the equipment and supplies they will be bringing with them.

Set up. Using whatever resources are appropriate, from commandeered structures to flags and signs, banner tape, or volunteers pointing the way, the treatment officer must set up the area for prioritized patient care and for forward movement of patients. Consider what you want to keep in (staff, supplies, patients) and keep out (freelancing providers, bystanders, physical hazards), and establish a clear route (from triage, into treatment, and out to transport). Think “keep in, keep out, clear route.”

Move forward. Often, the first patients in the treatment area are those least injured. Keep in mind that, depending on the patients, they may be able to assist in moving more seriously injured patients. Children, the elderly, or mobility-challenged patients may be relatively uninjured but may still require resources to move them forward and keep them safe.

Treatment area structures, staff, and equipment provide care to patients in order of triage priority but always while flowing from triage, through treatment, on the way to transport.

Transport

Perhaps the most challenging assignment, the transport officer, is the key to forward movement of patients. This position often requires at least one assistant. (3, 6)

Size up. The transport officer needs to size up the patients, ambulances, and destinations. The number and severity of patients determine the ambulances (or other vehicles) that may be needed and the destinations to which they will be transported. This information will help the transportation officer to determine the best locations for connecting patients in the treatment area with transporting ambulances or other vehicles.

Set up. The transport officer must establish a method that will, at a minimum, rapidly track patients with priority, the ambulance in which they were transported, and their destination.

To facilitate the forward movement of patients, transport officers should consider the best place to load patients, connecting the patient treatment area and the staging ambulances. Transport officers or their designees should also determine routes of transport from the scene to the destinations. This is important not only because mutual-aid resources may not be familiar with the best routes but also because normal routes may be affected by traffic disruptions.

Move forward. The transport section focuses on helping patients get loaded into vehicles according to priority, tracking those patients, and providing destinations and clear routes to the transporting vehicles; providing incident command with reports; and communicating with destinations to ensure that they are prepared to receive patients.

Bus collision incidents can be overwhelming, but by quickly identifying the number of patients and the severity of their injuries, the problems/hazards, and partners/resources, you can start to bring things under control.

Stack the cards in your favor by coordinating with your resources and stakeholders ahead of time. When a bus collision occurs, be ready to take command or coordinate with command on arrival and use triage, treatment, and transport to provide priority treatment and to continually and effectively move patients forward to definitive care.

Your agency will benefit from using these concepts, even at smaller incidents. Practicing these fundamentals at lower-level, more frequently encountered incidents will test your ability to apply these principles at larger incidents; and, when things go well, it will increase your crews’ confidence that they will be able to handle larger, more complex scenes.

State, regional, or local procedures will typically define the expectations of each role at a bus collision, but virtually every role can be made more manageable by using the three-step method of size up, set up, and move forward.

References

1. Nirupama, N. & Hafezi, H. “A short communication on school bus accidents: a review and analysis.” Nat Hazards 74, 2305–2310 (2014).

2. Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. Large Truck and Bus Crash Facts. fmcsa.dot (2017). Available at: https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/safety/data-and-statistics/large-truck-and-bus-crash-facts. (Accessed: 15 June 2017).

3. The Federal Interagency Committee on Emergency Medical Services. National Implementation of the Model Uniform Core Criteria for Mass Casualty Incident Triage. (ems.gov, 2013).

4. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Emergency Care and Transportation of the Sick and Injured. (Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2016).

5. Pan American Health Organization. Establishing a mass casualty management system. (Pan American Health Organization, 2001).

6. Federal Emergency Management Agency. Operational Templates and Guidance for EMS Mass Incident Deployment. (FEMA, 2012).

7. Federal Emergency Management Agency. National Incident Management System | FEMA.gov. fema.gov (2017). Available at: https://www.fema.gov/national-incident-management-system. (Accessed: 15 June 2017).

8. International Association of Fire Chiefs & Sweet, D. Vehicle Extrication. (Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2011).

9. Robertson-Steel, I. “Evolution of triage systems.” Emergency Medicine Journal 23, 154–155 (2006).

10. Jenkins, J., McCarthy, M. & Sauer, L. “Mass-casualty triage: time for an evidence-based approach.” Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 23 (2008).

11. Kahn, C. A., Schultz, C. H., Miller, K. T. & Anderson, C. L. “Does START Triage Work? An Outcomes Assessment After a Disaster.” Annals of Emergency Medicine 54, 424–430.e1 (2009).

12. Lerner, E., Cone, D. & Weinstein, E. “Mass Casualty Triage: An Evaluation of the Science and Refinement of a National Guideline.” Disaster Med Public Health Prep (2011).

13. Cone, D., Serrra, J. & Kurland, L. “Comparison of the SALT and Smart triage systems using a virtual reality simulator with paramedic students.” European Journal of Emergency Medicine (2011).

14. Kamali, B., Bish, D. & Glick, R. “Optimal service order for mass-casualty incident response. “European Journal of Operational Research 261, 355–367 (2017).

Rommie Duckworth is a fire captain and an EMS coordinator for the Ridgefield (CT) Fire Department and a former volunteer assistant chief. He is an author and award-winning educator with more than 28 years of experience working in career and volunteer fire departments, hospital health care systems, and public and private emergency medical services.