By Craig Nelson and Dane Carley

To defend a client properly, defense attorneys build a case by improving their situational awareness. They not only need to know the client’s history, story, and actions but also details of the case from all other possible points of view. They seek out information from law enforcement and about the judge, the jury, and the prosecutor. They need to consider what biases to address, who is an asset, and how the prosecutor intends to prove his or her position. This helps the defense attorney gather information about the case from all of the different angles. This preparation and research are required for every case. This approach increases the attorney’s odds of winning because it reduces the possibility of being blindsided. This preparation is also required to ensure that everything possible has been done to serve the client’s needs. Does the fire service treat its clients, the citizens, in the same manner?

Think about how your fire department prepares to serve your community. Has your department ever looked at the service you provide from all of the different angles? Have you asked those you serve what they expect and want instead of what you think they want from you? All successful businesses do this. If they do not, they do not stay in business very long. We believe this is the basis of a great process to increase fire department success. By following the HRO framework we have been discussing, you can build your fire department into a successful business.

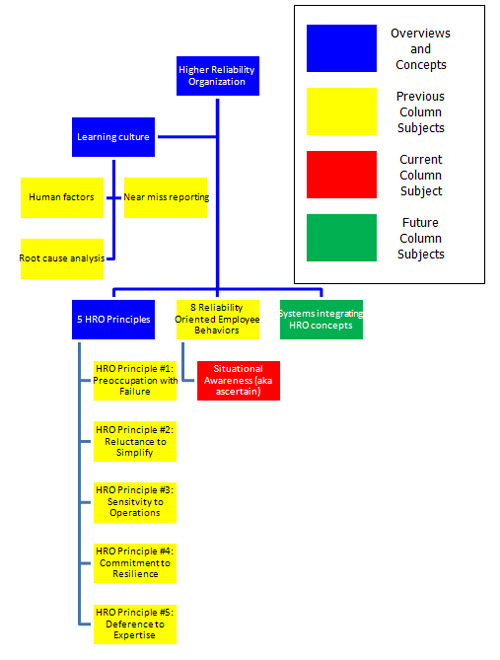

In our previous article, we introduced the eight Reliability Oriented Employee Behaviors (ROEBs) developed by Jeff Ericksen and Lee Dyer of Cornell University (2004).This column addresses the first of these important employee behaviors,–ascertain. For us in the fire service, this simply means gaining and maintaining situational awareness. It is important that we understand what is really happening in our operations and in our community. Although it is easy to think we know what is happening, how many times have you thought you knew exactly what was coming next only to be blindsided by the outcome? If you have ever experienced this, then you are human, and your situational awareness was incomplete. Something as simple as miscommunicating contributes to incomplete situational awareness. You might hear only part of something a person tells you as your brain begins to make sense of it by filling in the rest with what you expect to hear, even though it may not be what the person really said. These losses of situational awareness can occur in two primary areas for a fire department, operational and professional.

Operational situational awareness means knowing where you are and what is happening during daily activities such as fighting fires, extricating accident victims, and providing CPR. But it goes beyond knowing you are standing in front of a two-story, ordinary construction building on 123 Main St. at 0200 hours. It means knowing how your department’s standard operations interact with the entire situation. Examples of operational situational awareness that go beyond the basic awareness include the following: predicting how venting the roof is going to affect the crew searching on the second floor; understanding how decades of command and control affect information flow up the chain of command, and how the organization’s culture drives members. This information relates directly to the HRO principles we presented previously (Tailboard Talk columns from November, September, and August).

As a fire service, operational situational awareness comes easily to us because we study and train on this regularly. We set up a command structure and identify the immediate problem and possible solutions quickly at an emergency scene. As Gordon Graham teaches, this is a high-risk but also a relatively high-occurrence situation that we typically solve successfully (we do it a lot, so we are pretty good at it).

However, being good at something can also lead you to miss subtle signs because it makes it easier to fall into routines (complacency) at an emergency scene. Senior firefighters prioritize high volumes of information effectively. This helps them recover from unexpected events and develop new plans of action but may lead to missing important details. Younger firefighters tend to have an eye for detail because they typically do not process the large volumes of information as quickly and, therefore, catch more of the details (LeSage, Dyar, & Evans, 2011). What does this all mean? It means that by working well together and listening to everyone at a fire scene, we gain much better situational awareness.

However, we only spend a portion of our time on an emergency scene. While we are busy focusing on operational situational awareness, which is extremely important, we often forget professional situational awareness (or do not realize that it exists).

Professional situational awareness means being aware of what your citizens think of your department, what the council thinks of the department, and how your services align with all of their expectations–not just your expectations (remember the attorney example). The professional aspect of situational awareness is much like peeling the layers of an onion because it covers politics, budgets, grants, industry trends, and much more.

Just as junior and senior fire department members working together improve operational situational awareness, the fire department and community working together improve professional situational awareness. Has your department ever asked the community the following:

- What services do citizens expect the department to provide?

- What does the community feel is a fair cost for those services?

- What new services would the community like to see provided in the future?

- What services does the department provide that the citizens consider redundant or unnecessary?

- How do current events affect their lives, and what ideas do they have for services the department can adopt to help?

Instead of the department deciding what services to provide, we should start looking at this issue proactively from the viewpoint of the community we serve. This will help us to develop an understanding of how public support affects staffing, apparatus, stations, and so on. Improving the understanding of the resources your community will support may lead to increased resources, which improves resiliency and operational awareness.

If we look at struggling or obsolete businesses, we find that they often missed their customers’ desires; lacked innovation, which led to reacting to unforeseen external pressures; and operated under ineffective management or business models (Davis, 2011). Has the fire service fallen into the same trap? Apple provides products its customers want, which drives its growth. Meanwhile, Kodak suffers because the company reacted to digital photography too late. Does the fire service want to increase its situational awareness and become Apple, or does it want to keep the blinders and be Kodak?

From an officer’s point of view, that means

- Asking your people about hurdles within the department (limiting standing operational guidelines) preventing them from providing a quality service to the community.

- Seeking information from those on the streets about their experiences in the community.

- Looking at potential future challenges to gain situational awareness about new revenue sources, operating costs, and services that will not only help the fire service survive but also make it thrive.

- Asking the citizens what services are important to them and what operating costs are acceptable to provide those services.

From a firefighter’s point of view, that means

- Supporting the department’s initiatives.

- Bringing constructive criticism forward with possible solutions.

- Getting to know the citizens in the community because in their eyes you are the department.

- Reporting your experiences, hurdles, or ideas to the administration.

This month’s behavior is critical to emergency scene management but also professional viability. However, until the chiefs get their own near-miss reporting system for a department’s professional survival, we do not have any professional situational awareness case studies (would a professional near-miss reporting system be a good idea?). In the meantime, we are providing an operational one. The general key to either form of situational awareness is realizing that we often see what we want to see and align the incoming information with our beliefs. Therefore, we must step back and seek out challenging information.

Case Study

The following case study is from www.firefighternearmiss.com. The near miss report, 11-0000357, is not edited. We were not involved in this incident and do not know the department involved so we make certain assumptions based on our fire service experience to relate the incident to the discussion above.

|

Event Description As I write this I am on light duty from this event. While fighting a fire at a third story apartment, I walked out of the back of an apartment and fell three stories to the ground. Prior to my crew getting to the fire, we heard several reports of explosions, but paid no attention. We proceeded in the fast attack mode and went for the seat of the fire. I was on the truck that day and was first through the door. I did a right hand search and, as I turned a corner to keep searching, walked right out the back of the apartment. An occupant had left a propane heater on to keep his pet rabbits warm on the balcony of the apartment. The propane tank failed and the tank basically blew the back sliding glass door out along with the supporting balcony. I never saw it and that’s why I am writing this today. I will only be out three weeks and my injuries are minor, but, had I listened to the dispatchers while en route, I may have proceeded with more caution.

A 360 would have done wonders for our attack. Nobody ever did it, so the situation was never communicated. Regardless of that, I need to make sure that my size-up begins with the alarm and that I process all I can. |

Discussion Questions

1. The firefighter likely heard on dispatch, “apartment fire.” Based on the discussion above, what could have contributed to the firefighter’s missing this piece of information about the explosion?

2. What are some ways a fire department can gain community input and improve its professional situational awareness?

3. What are some examples of programs in your department or neighboring departments that include these qualities:

a. A public-private partnership.

b. Entirely or largely evolved from public input.

4. What are some categories for improving a business/department?

Possible Discussion Answers

1. A person’s mind hears pieces of information that align with what the person believes is happening–it is called cognitive dissonance. This is why it is so important to seek out information that challenges your perception of the event whether it is an emergency, training, personnel, or a budget issue.

2. A fire department can gain community input using online polls, open forums, discussions with civic groups, advertising opportunities to contribute in utility bill mailers, or opening discussions on local talk radio shows. One method that has shown to work well is publicizing the budgeting process. As an example, Washington State asked itself which of the 10 state functions are most important, chose to fund them within a certain dollar amount, and then asked the departments providing those functions to prioritize their specific programs and the associated costs. When the list of programs exceeded funding, the department cut the program. This led to great discussion about what was important and what a service was worth to the citizens (Osborne & Hutchinson, 2004).

3. Some national examples for discussion question #3 include

a. Physician extender program (http://www.azcentral.com/community/mesa/articles/0125mr-trvpa0125.html)

b. Public Access Defibrillators (http://www.firedepartment.org/community_outreach/pad.asp)

c. Business risk inventory and recovery capability assessment as part of fire prevention inspections

d. Providing emergency response to citizens with special needs (http://tailboardconsulting.com/tailboard_web_002.htm)

e. Community Paramedics (http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/hpsc/hep/transform/dec10documents/communityparamedic.pdf)

4. Some possible answers:

a. New service areas (community paramedic, clinics in fire stations)

b. Financial structure (Fire Protection Districts)

c. Excellent customer service (think Brunacini)

d. Technology

e. Management / business model (Crew Resource Management, HRO)

Where We Are Going

Next month’s column discusses the second reliability-oriented employee behavior of communicating. Communicating is about reporting failures immediately and discussing concerns to avoid the Abilene Paradox. We would appreciate any feedback, thoughts, or complaints you have. Please contact us at tailboardtalk@yahoo.com or call into our monthly Tailboard Talk Radio Show on Fire Engineering Blog Talk Radio.

References

Davis, S. (2011, December 05). 5 Brands Most Likely to Be Gone by 2015. Retrieved December 06, 2011, from Forbes: http://www.forbes.com/sites/scottdavis/2011/12/05/5-brands-most-likely-to-be-gone-by-2015/

Ericksen, J., & Dyer, L. (2004, March 1). Toward A Strategic Human Resource Management Model of High Reliability Organization Performance. Retrieved February 18, 2010, from CAHRS Working Paper #04-02: Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies: http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cahrswp/9

LeSage, P., Dyar, J. T., & Evans, B. (2011). Crew Resource Management Principles and Practice: Developing a Culture for Open Communications. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Osborne, D., & Hutchinson, P. (2004). The Price of Government: Getting the Results We Need in an Age of Permanent Fiscal Crisis. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Craig Nelson (left) works for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department and works part-time at Minnesota State Community and Technical College – Moorhead as a fire instructor. He also works seasonally for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources as a wildland firefighter in Northwest Minnesota. Previously, he was an airline pilot. He has a bachelor’s degree in business administration and a master’s degree in executive fire service leadership.

Dane Carley (right) entered the fire service in 1989 in southern California and is currently a captain for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department. Since then, he has worked in structural, wildland-urban interface, and wildland firefighting in capacities ranging from fire explorer to career captain. He has both a bachelor’s degree in fire and safety engineering technology, and a master’s degree in public safety executive leadership. Dane also serves as both an operations section chief and a planning section chief for North Dakota’s Type III Incident Management Assistance Team, which provides support to local jurisdictions overwhelmed by the magnitude of an incident.

Previous Articles

- Tailboard Talk: More PPE or Improved Fire Behavior Training?

- Tailboard Talk: Deference to Expertise

- Tailboard Talk: Not Bulletproof But Close — A Commitment to Resilience

- Tailboard Talk: A Sensitivity to Operations

- Tailboard Talk: K.I.S.S. or Not? A Reluctance to Simplify

- Tailboard Talk: Mistakes Even Happen to Firefighters: A Preoccupation with Failure

- Tailboard Talk: Why Do We Play the Blame Game? Let’s Turn It on Its Head!

- Tailboard Talk: Near Miss Report

- Tailboard Talk: HROs Use Human Factors to Improve Learning Within the Organization

- Tailboard Talk: HROs Use Human Factors to Improve Learning Within the Organization

- Tailboard Talk: Introduction to Higher Reliability Organizations