By Craig Nelson and Dane Carley

Firefighters are working at a three-alarm apartment fire on the top floor. The fire is in a three-story, wood-frame apartment building built in the early 1990s (e.g., truss roof). Crews aggressively attack the fire within the context of a strong Incident Command System (ICS) organization that develops great situational awareness among all of the crews operating on scene. Suddenly, the roof partially collapses, and a firefighter issues a Mayday because the collapse cuts off his retreat. He appears at a third-floor window, so a crew on the ground, without an order from command, brings a ladder to his window and removes him to safety. Is this freelancing or showing initiative? Is it freelancing if the situation is not a Mayday or ends unsuccessfully? Why might it be labeled differently? It is easy to label events gone wrong as freelancing. We know freelancing is bad, but do we have a tendency to overlook positive outcomes of freelancing by calling them heroic or using them as an example of taking initiative? Does the outcome of a situation determine what we call our operations? It often does.

We often label firefighters who were in the right place at the right time heroes or great firefighters, but those who were in the wrong place at the wrong time are often labeled as poor firefighters. We are not leaving good firefighting to luck or saying that intelligence, skills, experience, and training do not make for better firefighters; we are just saying that sometimes the outcome of a situation is beyond our control and luck can determine how the situation is looked at in the future. It stems from a societal norm dating back to the 1400s, judging an action on the outcome (Dekker, 2011) …but that is a whole other can of worms to open in another article.

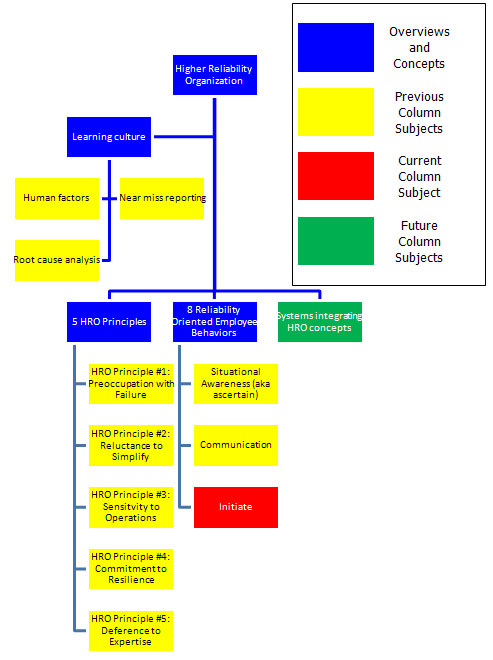

Our last article introduced communication barriers and solutions, the second of the eight Reliability Oriented Employee Behaviors (ROEBs) developed by Jeff Ericksen and Lee Dyer of Cornell University (2004). We move forward this month by looking at the third of these important employee behaviors, the ability to initiate. For us in the fire service, this simply means that fire personnel with the ROEBs we are discussing have developed an ability to recognize an adverse and unexpected event and to react to it appropriately.

Showing Initiative

The intention of ICS is to develop a shared understanding of the situation. That way, firefighters know what actions contribute to resolving the problem. This is something the fire service recognizes as developing situational awareness. Developing strong situational awareness throughout the ICS structure helps firefighters react to adverse events appropriately. But developing situational awareness requires a lot of relevant communication. As we talked about in last month’s article, communication is what develops situational awareness; the more intense a situation is, the more communication we should hear.

Contrary to what seems to be a common view of ICS, more communication (information) should be going up the chain of command than down, to help the incident commander (IC) develop situational awareness to determine appropriate orders. Good orders come from good decision making based on as much relevant information as possible moving up the chain of command. If you have ever been IC, would you rather have a lot of relevant information from which to base decisions, or would you rather do most of the talking, giving out more orders rather than receiving information? This is not to imply that every bit of information should be passed on to the IC, but all of the relevant information, which we will call “intelligence.” Klein found that experienced firefighters (those meeting certain criteria including 10-plus years of experience) have an intuitive ability to determine what information is important (intelligence), which is the information that should be passed up the chain of command (Klein, 1998).

ICS is about allowing firefighters to react — to show initiative — on the fireground. The difference between freelancing and showing initiative is that firefighters properly reacting to a situation and showing initiative will communicate their actions and intelligence to command, whereas a freelancer would not communicate what is happening. Firefighters reacting to a situation because of their situational awareness do so appropriately and safely and then pass their actions up the chain of command to maintain everyone’s situational awareness.

However, ICS is only a tool. Using it does not automatically develop situational awareness, so we need to be aware of impending problems that may indicate a need to reassess and regroup. We have developed a working list of “flags” through researching and teaching fire service materials. We have then put them to use by applying them in our fire service work to make our operations safer and more reliable. These flags are not intended to be a comprehensive list but are some examples of events that should trigger a light bulb in your head warning you of potential hazards because they indicate that situational awareness is being lost. Therefore, these factors are indicators of a scene that may be escalating and should cause firefighters to consider regrouping. They include the following:

- The situation is not making sense.

- The events involve children.

- You feel overwhelmed.

- Communication patterns are poor, missing, or overwhelming.

- You feel the need to rush or speed.

- You are focusing on one task at the expense of many others, or you are distracted.

- The perception does not match reality–something that should have happened did not happen.

Let’s put these indicators into a story to illustrate where they may appear. Units respond to a report of a fire with a child trapped on the second floor (flag — event involving children). We know that calls involving children are one of the most likely to trigger stress in firefighters, which “uses up” decision-making space in the brain, contributing to poor decisions. This is like a big software program running on a hard drive in a computer that causes everything else to slow down. Child calls cause us abnormal stress, reducing our ability to make appropriate decisions and to rush or take unusual risks.

The first unit arrives on scene to find a fire extending toward the front of the house, from the kitchen on the first floor; neighbors are saying children are in the house. The captain feels a need to rush into action (flag — rushing) but feels overwhelmed by the decision process (flag — overwhelmed) of attacking the fire or performing vent-enter-search (VES) because of the stressors. The captain chooses VES because of a single-task focus on rescuing the children at the expense of protecting the crews searching above the rapidly advancing fire (flag — single-task focus). We are not saying this is the right or wrong choice; we are only illustrating the decision points and how the flags may appear using an example.

The battalion chief arrives and begins making sense of the situation. He recognizes that the VES crew has been gone longer than expected and should have appeared by now (flag — something should have happened that did not). The chief recognizes that the crew may be in trouble, steps back for a second to assess resources and regroup, then redirects crews to attack the fire to protect the VES crew that may be in trouble upstairs.

Adaptability is critical to survival…on the fire ground and in today‘s political environment

The thing about flags is that they are subtle. None of these flags typically stands out on its own. Unless you are in tune with your own personal flags, you may miss them. Think of the times things did not go well. Now think about what your flag might have been for that situation. The above list of flags comes from many sources; it is not comprehensive or intended as a “safety list.” We developed this list from our personal experience and case studies. They are often lessons we or others have learned the hard way. To find flags, simply follow events backward when things went wrong and look for signs that might have been noticeable earlier had someone been looking for them.

The last type of initiative we are going to discuss is asking for help when you are unsure of what is happening or the incident is growing too fast. Incidents grow exponentially; yet, we typically add resources linearly. Often, there are not enough resources on scene until the incident has peaked and you catch up with it on the down side. How often have you heard an IC go straight from a second alarm to a fourth alarm? It seems like we add a second, then a third, and then, begrudgingly, a fourth alarm–almost as if in defeat. However, each consecutive alarm means pulling resources from farther away, so the time until resources arrive is increasing at the same time the fire is growing.

One sign of an expert is he recognizes his limitations. (Klein, 1998) An IC asking for help, whether it is more personnel or personnel with specialized knowledge, is not a sign of weakness. It is, rather, a sign that you are an expert decision maker who recognizes your limitations.

Sometimes, a scene is going to continue escalating regardless of how well you react. In this case, stopping and regrouping shows initiative. The Phoenix (AZ) Fire Department showed great initiative on a medical call, transforming it into a hazardous materials call. In this video, we see the firefighters taking initiative by recognizing that things weren’t making sense (flag, regrouping and getting more help. They use all of the types of initiative discussed here on one call. Check out the video on YouTube at Phoenix FD CO2 incident video as part of this month’s case study.

We are going to change our case study format this month. We pulled a near miss report from the national Firefighters Near Miss Web site below, but we are also including a link to a 20-minute video of the same incident from the Phoenix Fire Department (thanks, Phoenix FD for sharing this). The firefighter near miss report number is 11-0000303. Then link to a video about the same incident at YouTube (http://youtu.be/eY__H-CMvw0).

|

Event Description

At 2117 hours the Haz Assignment was dispatched. One thing to note was that the patient information on the mobile computer terminal still only had information from the initial fall injury. I’m not sure how this could have been fixed, but updated patient information would have been helpful en route. Battalion chief [1] assumed command and assigned [Engine 2] to Haz Sector. [Engine 2] and Squad [1] made entry into the building in turnouts and SCBAs. The goal of the entry was to meter the basement for what was suspected to be a Co2 leak. The manager of the restaurant told the crews that they had just had the Co2 tank filled a couple of hours prior to the call. The crews made entry with two combustible gas indexing (CGI) meters and two natural gas meters. As the crews descended the basement stairwell, they started to get decreased O2 readings and slightly increased volatile organic compound (VoC) readings on the CGI meters. As the crews continued into the basement, the O2 readings continued to decrease; the lowest reading was 17.5%. One of the many interesting things about this call was the readings the crews were getting on the natural gas meters. The meters were reading 100% LEL. When switched to %, gas the readings were 25%. The readings were obtained at ground level and at ceiling level. These readings prompted Haz Sector to exit the building and start to mitigate the potential hazards. They shut off the gas at the meter and attempted to shut down the power from the exterior. It was determined that another entry was necessary to shut off the power to the building and investigate the Co2 tank. Haz Sector made a second entry into the building and secured the power to the building while monitoring the air to ensure there was no risk of a spark causing ignition. Haz Sector then re-entered the basement to investigate the Co2 tank. They found a broken line on the tank and were able to shut down the tank to mitigate the hazard. After exiting the building, Haz Sector made a plan to ventilate the building. A confined space fan and flexible ducting were used off [Squad 1]. This method of ventilation was chosen due to the heavier than air gas in a below grade location. The ventilation was complete after about 30 minutes. Haz Sector did a final entry and obtained Zero readings on all the meters. The two members off [Engine 1] were transported to the hospital for further evaluation. This can truly be deemed a “near miss.”

Lessons Learned -Fire Department will contact the manufacturer of our natural gas meters to inquire about the Co2 readings on what is supposed to be a natural gas specific meter. -We will also check to see if we can use [other meters] with the sensors we have and do a conversion for Co2. -The on-site Co2 monitors at the restaurant didn’t function. -Some fast food restaurants have basements. -The gas water heater was located in the basement, so the potential for a gas leak and source of ignition existed. -The ventilation profile was difficult because of a heavier-than-air gas in a basement. -Gas Employee initial responder had to be told more than once to exit the hot zone; hot zone management is challenging on such a large-scale scene. -[Engine 1] did a great job of identifying the hazard, evacuating the building, and calling for the appropriate response. Crews did a great job of investigating and mitigating the hazard. ****Always suspect a potentially toxic environment when responding to any restaurant, convenience store, or any structure that has these systems in place–especially in basement areas.**** |

Discussion Questions

- How many times did the Phoenix crew stop, back out, and regroup?

- How many people were hurt in this incident handled the way it was?

- How many people could have been hurt?

- List some flags for this event.

- List some of your own flags.

Where We Are Going

Next month’s column studies the fourth reliability oriented employee behavior of deploy. Deploying focuses on switching tasks and roles quickly so that helps arrives where it is needed, when it is needed–something the fire service does well. We would appreciate any feedback, thoughts, or complaints you have. Please contact us at tailboardtalk@yahoo.com or call into our monthly Tailboard Talk Radio Show on Fire Engineering Blog Talk Radio.

References

Dekker, S. (2011). Drift Into Failure: From Hunting Broken Components to Understanding Complex Systems. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company.

Ericksen, J., & Dyer, L. (2004, March 1). Toward A Strategic Human Resource Management Model of High Reliability Organization Performance. Retrieved February 18, 2010, from CAHRS Working Paper #04-02: Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations, Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies: http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cahrswp/9

Klein, G. A. (1998). Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Craig Nelson (left) works for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department and works part-time at Minnesota State Community and Technical College – Moorhead as a fire instructor. He also works seasonally for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources as a wildland firefighter in Northwest Minnesota. Previously, he was an airline pilot. He has a bachelor’s degree in business administration and a master’s degree in executive fire service leadership.

Dane Carley (right) entered the fire service in 1989 in southern California and is currently a captain for the Fargo (ND) Fire Department. Since then, he has worked in structural, wildland-urban interface, and wildland firefighting in capacities ranging from fire explorer to career captain. He has both a bachelor’s degree in fire and safety engineering technology, and a master’s degree in public safety executive leadership. Dane also serves as both an operations section chief and a planning section chief for North Dakota’s Type III Incident Management Assistance Team, which provides support to local jurisdictions overwhelmed by the magnitude of an incident.

Previous Articles

- Tailboard Talk: Do Firefighters Talk Too Much or Not Enough?

- Tailboard Talk: Do You Really Know What Is Happening With Your Fire Department?

- Tailboard Talk: More PPE or Improved Fire Behavior Training?

- Tailboard Talk: Deference to Expertise

- Tailboard Talk: Not Bulletproof But Close — A Commitment to Resilience

- Tailboard Talk: A Sensitivity to Operations

- Tailboard Talk: K.I.S.S. or Not? A Reluctance to Simplify

- Tailboard Talk: Mistakes Even Happen to Firefighters: A Preoccupation with Failure

- Tailboard Talk: Why Do We Play the Blame Game? Let’s Turn It on Its Head!

- Tailboard Talk: Near Miss Report

- Tailboard Talk: HROs Use Human Factors to Improve Learning Within the Organization

- Tailboard Talk: HROs Use Human Factors to Improve Learning Within the Organization

- Tailboard Talk: Introduction to Higher Reliability Organizations