The system is the sum of all the resources available to meet the organization’s mission. These include the firefighter’s and officer’s experiences, training, and education (i.e., their wisdom). It includes the entire infrastructure and hardware: stations, apparatus, networks, agreements, technology, and engineering. The system is built on tradition since service delivery must meet the historic needs of the community. The system is also built on probability. Leaders build organizations anticipating the needs of the community or citizens. What determines when a situation will overwhelm the system? In the fire and emergency services, natural disasters many times quickly challenge the system.

Tornado

Although the fire and rescue department has adequate resources to handle “routine” fires and medical emergencies, multiple-alarm fires, and mass casualty incidents involving shootings and vehicle crashes, how prepared is a department to handle a catastrophic event like an Enhanced Fujita Scale (EF-3) tornado (severe, with winds of 136-165 miles per hour) striking a populated commercial business district and neighborhoods? How prepared is it when the situation involves miles of destruction, with entire neighborhoods and structures flattened? On April 28, 2008, such a tornado struck Suffolk,Virginia, quickly overwhelming the emergency response system (photo 1).

(1) Photos courtesy of Suffolk (VA) Department of Fire & Rescue.

Critical decision makers must recognize when the situation overwhelms the system. No single organization in municipal or county government alone can solve situations that overwhelm the system. The system is designed to provide services that meet the needs of the citizens and responders and to support incident commanders and critical decisions when a situation becomes large and complex. The EF-3 tornado’s path struck a commercial area in Suffolk before heading toward a residential neighborhood, damaging or destroying 462 residential properties and 24 commercial/business properties, resulting in $29.8 million in property damage (photo 2).

But the system is not designed or prepared to support responders or citizens for every situation. For the system to rebound and survive when a situation overwhelms it, its leaders must ensure that its services are refined, contemporary, and relevant. Emergency responders must be trained and equipped with the latest technologies and techniques and be aware of industry best practices. The system is larger than a single team, bureau, or department. The system should be designed to be flexible when situations stress the ordinary.

After the 2008 Suffolk tornado, so many structures needed to be searched. Fortunately, mutual aid and responders from 10 fire and rescue departments; Virginia’s state police, emergency management, and environmental quality agencies; and the National Weather Service supplemented Suffolk’s overwhelmed system and allowed for a favorable outcome to the affected citizens (photo 3).

A flexible system will allow for outcomes that provide for the greatest amount of good for the greatest number of people. When presented with a situation that challenges the system, critical decision makers make the difference. A leader skilled and trained at making critical decisions can turn a poor situation into a better one and allow the system to prevail.

Bettering the Situation

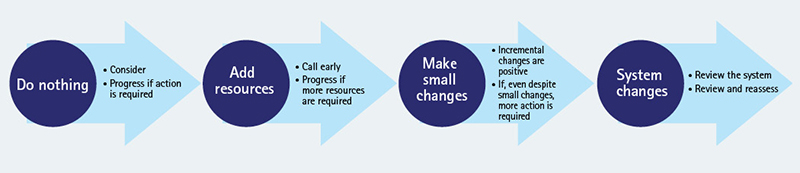

You can use the following method in Figure 1 to make the situation better when the system fails: Consider 1. What happens if you do nothing? 2. What additional resources do you require, and when can you reasonably expect them to arrive? 3. What small, incremental changes can you make to the situation to shift it toward a positive outcome? 4. Are you using all available systems? If not, can you use them to better the situation?

Figure 1. System Failure: How to Improve the Situation

Use this pathway to better the situation when the system fails. Source: Barakey, Michael. Critical Decision Making: Point-To-Point Leadership in Fire and Emergency Services. Fire Engineering Books and Videos, 2018.

Apollo 13

A well-documented, historical example of a situation that overwhelmed the system is National Aeronautic and Space Administration’s (NASA’s) Apollo 13 mission. As the lives of three astronauts—James A. Lowell Jr., John C. Sigwart Jr., and Fred W. Haise Jr.—were in peril, engineers, staff in the mission control center, and the astronauts all used their combined wisdom to make critical decisions that allowed the system to ultimately defeat the situation. This mission became known as a “successful failure.”1 Apollo 13 was NASA’s third lunar landing attempt, after both Apollo 11 and Apollo 12 had successfully landed on the moon in 1969. How could this mission be considered a “successful” failure? The experience gained by rescuing the crew allowed NASA to classify Apollo 13 as a successful failure.

On April 13, 1970, nine minutes after the crew finished a TV broadcast, an explosion occurred in one of the oxygen tanks outside the spacecraft. After the explosion, Astronaut Jack Sigwart made the historic statement, “Houston, we’ve had a problem here.”2 One oxygen tank blew up, causing the other oxygen tank to fail, which resulted in some of the astronauts’ oxygen supply escaping into space. In addition, warning lights indicated the loss of two of the craft’s three fuel cells that provided Apollo 13 electricity. One hour and 29 seconds after the explosion, mission control and the astronauts were contemplating how to use the lunar module as a “lifeboat” to return the crew to earth safely.2

The situation was dire and the system needed to answer a simple question: How do we to get the astronauts back safely to Earth? The incident objectives changed in an instant. The original objective was to land on the moon; now it was to get the crew home alive. The strategies instituted to support the objective were outside NASA’s policies and procedures. The crew had to find a way to use the lunar module to get the crew back into earth’s orbit and then transfer into the command module so that they could safely reenter Earth’s atmosphere. The system had failed and the situation was bleak. If the situation could not be changed, the three astronauts would die. Mission Control (Houston) had to develop completely new procedures and test them in a simulator. While engineers worked on the procedures, the astronauts moved to the lunar module. Engineers worked to develop a procedure for the lunar module’s descent engine to be used to get the crew home safely. Meanwhile, plans were developed to conserve water and oxygen, save power, and engineer a way to remove carbon dioxide from the lunar module.1 The situation was now more important than the system. The system had failed, but fixing the system was not the immediate desire of NASA’s leadership. The system needed to pull together and solve the situation at hand using critical decision-making skills. Apollo 13’s near miss is an example of NASA and three astronauts solving a critical incident. Both the situation and the system had failed. Many critical decisions were made in a compressed time to solve the problem.

Are You Prepared?

Is your department prepared for an event, incident, or situation that overwhelms the system? Prepare by performing an inventory of all resources in your fire and rescue department and all resources in your city or county that aid in large-scale incidents (the planning department; emergency management; law enforcement; media and community relations; building inspectors; public works; public utilities; mutual-aid departments in your region and state; and state and federal partners such as the state emergency operations command, state police, the medical examiner’s office, and so forth). Exercise and train on large-scale events that escalate into a situation that overwhelms the system. This can be accomplished with tabletop exercises and regional full-scale exercises.

Endnotes

1. NASA.gov. “Apollo 13.” NASA Web site. https://go.nasa.gov/42xIxlO.

2. archive.org. Apollo-13 (29). https://bit. ly/42y2HMA.

MICHAEL J. BARAKEY, CFO, is a 30-year fire service veteran and the chief of Suffolk (VA) Fire & Rescue. He is also a hazmat specialist; an instructor III; a nationally registered paramedic; and a neonatal/pediatric critical care paramedic for the Children’s Hospital of the King’s Daughters in Norfolk, Virginia. Barakey is the participating agency representative and former task force leader for VA-TF2 US&R team and an exercise design/controller for Spec Rescue International. He has a master’s degree in public administration from Old Dominion University and graduated from the National Fire Academy’s Executive Fire Officer Program in 2009. Barakey authored Critical Decision Making: Point-To-Point Leadership in Fire and Emergency Services (Fire Engineering Books and Videos), regularly contributes to Fire Engineering, and is an FDIC International preconference and classroom instructor.